Thomas Jefferson and education facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Jefferson

|

|

|---|---|

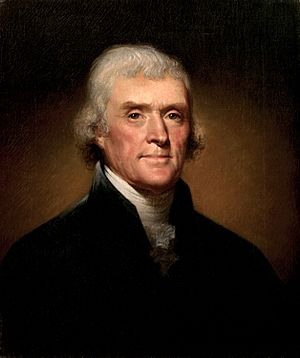

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800

|

|

| 3rd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 |

|

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 13 [O.S. April 2] 1743 Shadwell, Virginia |

| Died | July 4, 1826 (aged 83) Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Alma mater | The College of William & Mary |

| Occupation | Governor of Virginia, Statesman, planter, lawyer, philosopher, inventor, architect, teacher |

Thomas Jefferson believed that education was super important for everyone. After he was president, he founded the University of Virginia in 1819. This university was special because it was not connected to a church. Jefferson thought libraries and books were so important that he designed the university around its library.

In 1779, Jefferson suggested a public education system. He wanted schools to be paid for by taxes for three years for "all the free children, male and female." This was a very new idea for that time! If parents or friends could pay, children could stay in school longer.

Jefferson wrote down his ideas for public elementary education in his book Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). Later, in 1817, he proposed a plan for state-funded education just for boys. This plan included public grammar schools. Only the best students, or those whose parents could pay, would go on to higher education. The university would be the top level, only for the very best students. Virginia did not have free public education for younger kids until after the American Civil War.

Contents

- How Did Jefferson Learn?

- Jefferson's Love for Books

- Presidency and Education

- Later Years: Jefferson's Education Plan

- Jefferson's Ideas on Citizen Education

- Views on Classical Learning

- Views on Textbooks and Professors

- How Should Learning Be Organized?

- Views on Educational Conformity

- Views on Religion in Schools

- Images for kids

- See also

How Did Jefferson Learn?

In 1752, when he was nine, Jefferson started school with a Scottish minister. He began learning Latin, Greek, and French. He also learned to ride horses and loved studying nature. From 1758 to 1760, he studied with Reverend James Maury. During this time, he learned about history, science, and classic books.

At 16, in 1760, Jefferson went to The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg. He studied there for two years. He took classes in math, philosophy, and other subjects with Professor William Small. This professor introduced him to important thinkers like John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton. Jefferson also got better at French, always carried his Greek grammar book, played the violin, and read famous authors like Tacitus and Homer. He was very curious about everything. Family stories say he often studied for 15 hours a day! His friend, John Page, said Jefferson would leave his friends to go study.

While in college, Jefferson was part of a secret group called the Flat Hat Club. He lived at the College in a building now called the Sir Christopher Wren Building. He ate meals and attended prayers there. Jefferson also went to parties hosted by the royal governor, Francis Fauquier. He played his violin and developed a love for wines. After college, he studied law with George Wythe and became a lawyer in 1767.

Jefferson's Love for Books

Jefferson loved books and used them for learning his whole life. He collected thousands of books for his library at Monticello, his home. He also inherited many books from George Wythe. Jefferson always wanted to learn more. He once said, "I cannot live without books."

By 1815, Jefferson had 6,487 books. He sold them to the Library of Congress for $23,950. This helped replace the library's collection, which was destroyed in the War of 1812. Even though he sold his books to pay off debt, he immediately started buying more! The Library of Congress even named its website for federal information "THOMAS" to honor him. In 2007, a two-volume edition of the Qur'an from Jefferson's collection was used by Rep. Keith Ellison when he was sworn into the House of Representatives.

In 2011, part of Jefferson's personal library, 74 books, was found at Washington University in St. Louis.

Presidency and Education

Founding West Point Military Academy

People had talked about creating a national military school since the American Revolution. In 1802, President Jefferson, following advice from others like George Washington, finally convinced Congress to fund and build the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

On March 16, 1802, Jefferson signed a law that created a group of engineers. This group would be "stationed at West Point... and shall constitute a Military Academy." The goal was to train good officers for the army. These officers would be loyal to the new republic. Congressmen would choose the students, so they would represent the country's different areas. The US Military Academy at West Point officially opened on July 4, 1802. It became a place for scientific and military learning.

Later Years: Jefferson's Education Plan

A Plan for All of Virginia

In 1785, Jefferson proposed a system of public schools for Virginia. He wanted to "spread knowledge more generally through the mass of the people." He believed that all children should learn reading, writing, and basic math. He also wanted some talented students to learn Greek, Latin, geography, and more advanced math. The very best students would learn sciences. This plan would also give wealthy families good schools where they could pay for their children's education.

Jefferson's plan had three steps, with three types of schools:

- Primary schools: All children could attend for at least three years for free.

- Intermediate schools: For students who did well in primary school, or whose parents could pay.

- University: For the very best students whose parents could pay.

It is declared and enacted, that no person unborn or under the age of twelve years at the passing of this act, and who is compos mentis, shall, after the age of fifteen years, be a citizen of this commonwealth until he or she can read readily in some tongue, native or acquired.

Step 1: Primary School (Ages 6–8)

Jefferson suggested creating small school districts, called "wards." Each district would have a primary school and a teacher paid by taxes. Every family could send their children to school for three years for free. If a family wanted their child to stay longer, they would have to pay.

These schools would teach reading, writing, and math. They would also teach basic geography and history (Greek, Roman, European, and American). Jefferson thought it was important for all children to learn history. He believed that "apprising them of the past will enable them to judge of the future." He also thought these schools would teach children basic morals.

Jefferson did not want religious texts in these schools. He felt children were too young to understand complex religious ideas. However, he did want to teach children that happiness comes from a "good conscience, good health, occupation, and freedom in all just pursuits."

There is a certain period of life, say from eight to fifteen or sixteen years of age, when the mind, like the body, is not yet firm enough for laborious and close operations. If applied to such, it falls an early victim to premature exertion; exhibiting indeed at first, in these young and tender subjects, the flattering appearance of their being men while they are yet children, but ending in reducing them to be children when they should be men.

Step 2: Intermediate School (Ages 9–16)

Each year, an official would visit the primary schools. They would choose one boy whose parents were too poor to pay for more schooling. This boy would go to one of Virginia's 20 grammar schools for one to eight years. Other parents who could pay could also send their children.

In grammar schools, children would learn Greek and Latin, advanced geography, higher math, geometry, and basic navigation.

Jefferson believed that a child's memory is best between ages 8 and 16. He thought this was the perfect time to learn languages, which involve a lot of memorizing. He also thought this age was best for learning "tools for future operation," like "useful facts and good principles." He warned that if this time was wasted, the mind would become "lazy and weak."

After about two years, the "best genius" from each grammar school would be chosen to continue studying for six more years. The rest would leave. Jefferson said, "By this means twenty of the best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish annually, and be instructed, at the public expence, so far as the grammar schools go."

By that part of our plan which prescribes the selection of the youths of genius from among the classes of the poor, we hope to avail the state of those talents which nature has sown as liberally among the poor as the rich, but which perish without use, if not sought for and cultivated.

Step 3: University (Ages 17–19)

At the end of grammar school, half of the boys would leave. This group would include future grammar school teachers. The other half, chosen for being smart and having good attitudes, would study for three more years at the university. They would choose which sciences to study. Jefferson saw the university as the top of the education system. He suggested that the College of William and Mary should be made bigger to include "all the useful sciences."

Father of a University

After being president, Jefferson stayed active in public life. He became very focused on starting a new university. He wanted one that was free from church control. Students there could specialize in many new subjects not offered elsewhere. Jefferson believed that educating people helped create an organized society. He also felt that schools should be paid for by the public so that less wealthy people could attend. He had been planning this university for decades before it was founded.

We fondly hope that the instruction which may flow from this institution, kindly cherished, by advancing the minds of our youth with the growing science of the times, and elevating the views of our citizens generally to the practice of the social duties and the functions of self-government, may ensure to our country the reputation, the safety and prosperity, and all the other blessings which experience proves to result from the cultivation and improvement of the general mind.

His dream came true in 1819 with the founding of the University of Virginia. When it opened in 1825, it was the first university to let students choose all their courses. Jefferson was very involved with the university until he died. He invited students and teachers to his home. The famous writer Edgar Allan Poe was one of those students.

The university was one of the biggest building projects in North America at that time. It was special because it was built around a library, not a church. Jefferson did not include a chapel in his original plans.

Jefferson is famous for designing the University of Virginia and its grounds. His design showed his hopes for public education and a farming-based democracy in the new country. He called his campus plan the "Academical Village." Different academic areas were separate buildings, called Pavilions. These faced a grassy quadrangle, with each Pavilion having classrooms, offices, and homes for teachers. They all looked equally important and were connected by open walkways for student housing. Gardens and vegetable plots were placed behind the buildings, surrounded by wavy walls. This showed the importance of a farming lifestyle.

Jefferson's plan created a group of buildings around a central rectangular area called The Lawn. The academic buildings and their walkways lined both sides. The library, which held all the knowledge, was at one end, like the head of a table. The other end was left open for future growth. The Lawn gently sloped upwards in terraces to the library, which was in the most important spot at the top.

Jefferson liked Greek and Roman architectural styles. He thought they best represented American democracy. Each academic building had a two-story temple-like front facing the quad. The library was designed like the Roman Pantheon. The whole group of buildings showed how important non-religious public education was. Not having religious buildings emphasized the idea of separating church and state. This campus design is seen as a perfect example of how buildings can express ideas. A survey of architects even called Jefferson's campus the most important work of architecture in America.

The University was meant to be the highest level of Virginia's education system. Jefferson imagined that any young white male citizen of Virginia could attend if they had the right skills and achievements from earlier schooling.

Jefferson's Ideas on Citizen Education

Jefferson strongly supported public education. In a letter to George Wythe in 1786, he said that the most important law was "that for the diffusion of knowledge among the people." He believed that education was the only sure way to keep freedom and happiness. If people were not educated, they would remain "in ignorance." However, Jefferson did not believe in forcing parents to send their children to school. He thought it was better to allow a parent to refuse than to force a child to be educated against their father's will.

Views on Classical Learning

Jefferson was a big fan of classical learning, which means studying ancient Greek and Latin. He said, "For classical learning I have ever been a zealous advocate." He believed these languages were the "foundation preparatory for all the sciences." He thought they were best learned when young, between ages nine or ten, because memory is strong then.

He explained that classical languages help us in several ways:

- They provide "models of pure taste in writing," influencing modern writing styles.

- They offer the "luxury of reading the Greek and Roman authors in all the beauties of their originals."

- They contain "stores of real science" in history, ethics, math, geometry, astronomy, and natural history.

Jefferson believed that reading Greek and Latin authors in their original languages was a "sublime luxury." He also said, "I make it a rule never to read translations where I can read the original." However, he didn't think a super-detailed knowledge of these languages was needed, just a good understanding of the authors.

Views on Textbooks and Professors

Jefferson was okay with textbooks. He thought that professors, not school leaders, should usually choose the books for their classes. But he made one exception: if a professor wanted to use a book that taught ideas against the government's principles, Jefferson believed the leaders should step in. This was "to guard against such principles being spread among our youth."

Jefferson thought professors should be good at explaining things and know about many sciences, not just their own subject. He believed they should be able to talk with other scientists and help make decisions for the university. If a professor wasn't well-educated, Jefferson thought they would "incur...contempt, and bring disreputation on the institution."

How Should Learning Be Organized?

Jefferson wanted institutions where "every branch of science, useful at this day, may be taught in its highest degree." He listed important subjects for an American college education: classical knowledge, modern languages (especially French, Spanish, and Italian), math, natural philosophy (including chemistry and agriculture), natural history (including botany), civil history, and ethics.

He thought agriculture was a very important science. He believed that "in every College and University, a professorship of agriculture, and the class of its students, might be honored as the first." He also valued botany, saying it was "more at hand for his amusement" for a country gentleman.

Jefferson's plan for schools was simple:

- Elementary schools: Reading, writing, basic math, and general geography.

- District colleges: Ancient and modern languages, full geography, higher math, measurement, and basic navigation.

- University: All useful sciences at the highest level.

He disagreed with colleges that made all students follow the same course of study. He wanted students to have "uncontrolled choice in the lectures they shall choose to attend." He believed that the university should be based on "the illimitable freedom of the human mind." He said, "here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it."

Jefferson knew that schools wouldn't make students experts right away. He said, "We do not expect our schools to turn out their alumni already enthroned on the pinnacles of their respective sciences; but only so far advanced in each as to be able to pursue them by themselves."

He also believed that education should be practical. It should give every citizen the information they need for their daily lives. This included being able to read, write, do math, understand their duties, know their rights, and make good decisions. He thought history was important because "by apprising them of the past will enable them to judge of the future."

Jefferson warned against reading too many novels, which he called "poison." He thought they could make people dislike "wholesome reading" and lead to "a bloated imagination, sickly judgment, and disgust towards all the real businesses of life." He suggested reading some poetry and authors like Pope, Dryden, Thompson, Shakespeare, Moliere, and Racine for style and taste.

He wanted to "promote in every order of men the degree of instruction proportioned to their condition and to their views in life." He hoped that people would see the importance of education "on the broad scale."

Views on Educational Conformity

Jefferson believed that humans learn by imitating others. He said, "Man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him."

He worried about discipline in American schools. He felt that "premature ideas of independence, too little repressed by parents, beget a spirit of insubordination." This, he thought, was a big problem for learning. He suggested avoiding too many rules and letting students handle minor discipline themselves.

Jefferson also had strong opinions about American students studying in Europe. He thought it was dangerous because they might become "fascinated with the privileges of the European aristocrats." He believed this could make them dislike the "lovely equality" that rich and poor people enjoyed in America. He felt that the most learned and trusted Americans were those educated in their own country, whose "manners, morals and habits are perfectly homogeneous with those of the country."

He hoped that spreading knowledge among people would lead to "great advancement in the happiness of the human race." He believed that liberty was the "great parent of science and of virtue." He urged people to "preach... a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people."

Views on Religion in Schools

Jefferson believed there was a gap in education because religious instruction wasn't part of public institutions. However, he thought it was less dangerous to have this gap than to let public authorities decide on religious teaching. He also didn't want to favor one religious group over another.

He suggested encouraging different religious groups to set up their own teaching areas near the university. This way, their students could attend university lectures and use the library. He believed that bringing different religious groups together with other students would "soften their asperities, liberalize and neutralize their prejudices, and make the general religion a religion of peace, reason, and morality."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Jefferson y la educación para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Jefferson y la educación para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |