Tigran Petrosian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tigran Petrosian |

|

|---|---|

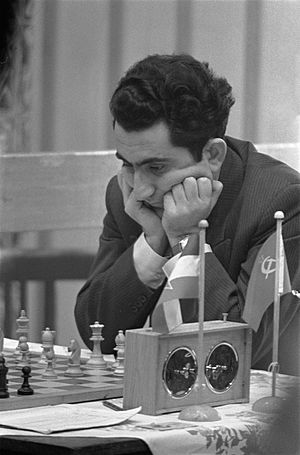

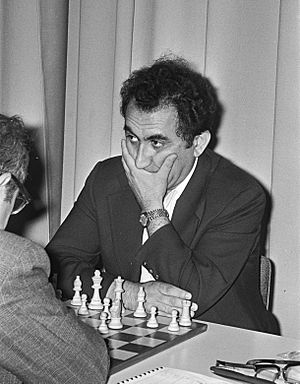

Petrosian in 1962

|

|

| Full name | Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Born | 17 June 1929 Tiflis, Georgian SSR, USSR |

| Died | 13 August 1984 (aged 55) Moscow, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Title | Grandmaster (1952) |

| World Champion | 1963–1969 |

| Peak rating | 2645 (July 1972) |

Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian (Armenian: Տիգրան Վարդանի Պետրոսյան, Russian: Тигран Вартанович Петросян; 17 June 1929 – 13 August 1984) was a famous Soviet-Armenian chess grandmaster. He was the World Chess Champion from 1963 to 1969. People called him "Iron Tigran" because of his super strong defensive playing style. He always focused on being safe and not letting his opponents attack. Petrosian is often seen as the person who made chess in Armenia very popular.

Petrosian tried to become World Chess Champion many times. He was a candidate eight times between 1953 and 1980. He won the World Championship in 1963 by beating Mikhail Botvinnik. He then successfully defended his title in 1966 against Boris Spassky. However, he lost his title to Spassky in 1969. He also won the Soviet Championship four times (1959, 1961, 1969, and 1975).

Contents

Early Life

Tigran Petrosian was born on June 17, 1929, in Tbilisi, which is now in Georgia. His parents were Armenian. As a child, Tigran loved to study, just like his brother and sister. He started playing chess when he was 8 years old. His father wanted him to keep studying, as he didn't think chess would be a good career.

During World War II, Petrosian became an orphan. He had to sweep streets to earn money. Around this time, his hearing started to get worse. This problem stayed with him for his whole life.

Petrosian used his food rations to buy a chess book called Chess Praxis by Aron Nimzowitsch. He later said this book helped him the most as a chess player. He also bought The Art of Sacrifice in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann. Another player who influenced him early on was José Raúl Capablanca. When he was 12, he started training at the Tiflis Palace of Pioneers. His coach, Archil Ebralidze, liked Nimzowitsch and Capablanca's ideas. This scientific way of playing chess helped Petrosian develop a strong, safe style. He learned openings like the Caro–Kann Defence. After only one year of training, he even played a draw against the famous Soviet grandmaster Salo Flohr.

By 1946, Petrosian became a Candidate Master. That year, he drew a game against Grandmaster Paul Keres. He then moved to Yerevan, where he won the Armenian Chess Championship and the USSR Junior Chess Championship. He earned the title of Master in 1947. To get even better, he studied Nimzowitsch's My System and moved to Moscow for tougher competition.

Becoming a Grandmaster

After moving to Moscow in 1949, Petrosian's chess career grew quickly. He came in second place in the 1951 Soviet Championship. This earned him the title of international master. In this tournament, he played against the world champion Botvinnik for the first time. Petrosian played a very long game, lasting eleven hours over two days, and managed to get a draw. His good result helped him qualify for the Interzonal tournament in Stockholm the next year. He became a Grandmaster by finishing second in Stockholm. This also qualified him for the 1953 Candidates Tournament.

Petrosian finished fifth in the 1953 Candidates Tournament. After this, his career seemed to slow down a bit. He often played for a draw against weaker players. He seemed happy to keep his Grandmaster title instead of trying harder to become World Champion. For example, in the 1955 USSR Championship, he didn't lose any games, but he only won four and drew the rest. Many of his draws were very short. People and chess experts in the Soviet Union didn't like this cautious approach.

However, Petrosian changed his style in the 1957 USSR Championship. He took more risks, winning seven games and losing four. Even though he only finished seventh, the Soviet chess community liked his new, more ambitious way of playing. He won his first USSR Championship in 1959. Later that year, he showed his tactical skills by beating Paul Keres in the Candidates Tournament. He won another Soviet title in 1961. His excellent play continued into 1962, when he qualified for the Candidates Tournament again. This time, it would lead to his first World Championship match.

1963 World Championship

After playing in the 1962 Interzonal tournament in Stockholm, Petrosian qualified for the Candidates Tournament in Curaçao. Other strong players like Bobby Fischer were also there. Petrosian, from the Soviet Union, won the tournament. He scored 17½ points, just ahead of two other Soviet players. Bobby Fischer later said that the Soviet players worked together to prevent him from winning. He pointed out that all 12 games between Petrosian and the other two Soviet players were draws. To prevent similar situations, FIDE (the world chess organization) later changed the rules for the Candidates Tournament.

Since he won the Candidates Tournament, Petrosian earned the right to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the World Chess Champion title. This was a long match of 24 games. Petrosian prepared by playing chess and also by skiing for several hours each day. He believed that being physically fit would help him in the later games of such a long match. Botvinnik was much older than Petrosian, which gave Petrosian an advantage. Petrosian's careful playing style was perfect for a match. He could wait for his opponent to make mistakes and then use them to his advantage. Petrosian won the match against Botvinnik with a score of 5 wins to 2 losses, with 15 draws. This made him the World Champion!

World Champion Years

After becoming World Champion, Petrosian pushed for a chess newspaper for the whole Soviet Union, not just Moscow. This newspaper became known as 64. Petrosian also studied at Yerevan State University. He earned a degree in Philosophical Science in 1968. His main project was about "Chess Logic, Some Problems of the Logic of Chess Thought."

In 1966, three years after winning the title, Petrosian was challenged by Boris Spassky. Petrosian successfully defended his title by winning the match. This was a big achievement, as it hadn't happened since 1934. However, Spassky won the next Candidates cycle. This meant he earned a rematch with Petrosian in 1969. This time, Spassky won the match by 12½–10½, and Petrosian lost his title.

Later Career

In 1976, Petrosian, along with other Soviet chess champions, signed a paper against Viktor Korchnoi. Korchnoi had left the Soviet Union. This was part of a long-standing disagreement between Petrosian and Korchnoi. In their 1977 match, they refused to shake hands or speak to each other. They even asked for separate eating and bathroom areas. Petrosian lost this match. He was also fired from his job as editor of 64, Russia's biggest chess magazine. Some people criticized him for not attacking enough, saying he lacked courage. But Botvinnik, a former world champion, defended him. He said Petrosian only attacked when he felt safe, and his greatest strength was in defense.

Some of Petrosian's later successes included winning tournaments in Lone Pine in 1976 and the Paul Keres Memorial in Tallinn in 1979. He shared first place in the Rio de Janeiro Interzonal in the same year. In 1981, he came in second place in Tilburg. It was there that he had his last famous victory, a surprising win against the young Garry Kasparov.

Personal Life and Death

Petrosian lived in Moscow from 1949. When asked if he was Russian, Petrosian replied, "Abroad, they call us all Russians. I am a Soviet Armenian."

In 1952, Petrosian married Rona Yakovlevna. She was an English teacher and interpreter. They had two sons.

Petrosian enjoyed many hobbies, including football, backgammon, cross-country skiing, table tennis, and gardening.

Tigran Petrosian died in Moscow on August 13, 1984, from stomach cancer. He is buried in the Moscow Armenian Cemetery.

Deafness

Petrosian was partly deaf and wore a hearing aid during his chess matches. This sometimes led to funny situations. Once, he offered a draw to another player, Svetozar Gligorić. Gligorić first said no, but then quickly changed his mind and offered a draw back. Petrosian didn't respond and later won the game. It turned out he had turned off his hearing aid and didn't hear Gligorić's offer! In 1971, he played a match in a noisy area. The noise didn't bother Petrosian, but it bothered his opponent, Robert Hübner, so much that Hübner quit the match.

Recognition and Legacy

At the time of his death, Petrosian was working on a book of chess lectures and articles. His wife, Rona, finished editing them. The book was published in Russian in 1989 and in English as Petrosian's Legacy in 1990.

In 1987, World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov unveiled a memorial at Petrosian's grave. It shows the laurel wreath given to Chess World Champions. It also has an image of the sun shining above the two peaks of Mount Ararat. This mountain is a national symbol of Armenia, Petrosian's homeland. On July 7, 2006, a statue honoring Petrosian was opened in Yerevan, on a street named after him. Petrosian was also honored on the Armenian 2,000 dram banknote.

Chess Olympiads and Team Championships

Petrosian was a key player for the Soviet Union's Olympiad team. He played in ten straight Olympiads from 1958 to 1978. He won nine team gold medals and one team silver medal. He also won six individual gold medals for his performance on his board. His record in Olympiad games is amazing: he only lost one game out of 129 played! This makes him one of the best Olympiad players ever.

He also played for the Soviet team in eight European Team Championships. He won eight team gold medals and four board gold medals in these events.

Playing Style

| This section uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves. |

Petrosian was a very careful and defensive chess player. He was greatly influenced by Aron Nimzowitsch's idea of prophylaxis. This means he spent a lot of effort stopping his opponent's attacks, even more than trying to make his own attacks. He rarely attacked unless he felt his position was completely safe. He usually won by playing steadily until his opponent made a mistake. Then, he would use that mistake to win without showing any weaknesses of his own.

This style often led to draws, especially against other careful players. But his patience and strong defense made him incredibly hard to beat. He didn't lose a single tournament game in 1962. His consistent ability to avoid losing earned him the nickname "Iron Tigran." Many chess experts consider him one of the hardest players to beat in chess history. Future World Champion Vladimir Kramnik called him "the first defender with a capital D."

Petrosian liked to play closed openings. These openings don't force his pieces into a specific plan too early. As Black, he often played the Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation and the French Defence. As White, he often used the English Opening. Petrosian sometimes moved the same piece many times in a few moves. This could confuse his opponents in the opening.

Many interesting comparisons have been used to describe Petrosian's style. One person said playing him was "like trying to put handcuffs on an eel. There was nothing to grip." He has been called a centipede hiding in the dark, a tiger waiting to pounce, a python slowly squeezing its victims, and a crocodile waiting hours for the right moment to strike. Boris Spassky, who became World Champion after Petrosian, said: "Petrosian reminds me of a hedgehog. Just when you think you have caught him, he puts out his quills."

Some people criticized Petrosian's style for being "dull." They thought his "ultraconservative" play was not as exciting as the "daring" Soviet chess style. His 1971 match with Viktor Korchnoi had so many draws that even the Russian newspapers complained. However, Svetozar Gligorić said Petrosian was "very impressive in his incomparable ability to foresee danger on the board and to avoid any risk of defeat." Petrosian replied to his critics by saying: "They say my games should be more 'interesting'. I could be more 'interesting'—and also lose."

Because of his style, Petrosian didn't win many tournaments, even though he often finished second or third. But his style was very effective in one-on-one matches. Petrosian could also play in an attacking way sometimes. In his 1966 match with Spassky, he won Game 7 and Game 10 with sacrifices. Spassky later said: "It is to Petrosian's advantage that his opponents never know when he is suddenly going to play like Mikhail Tal." (Tal was known for his aggressive attacks.)

The Positional Exchange Sacrifice

Petrosian was famous for using something called the "positional exchange sacrifice." This is when a player gives up a rook for a less valuable piece, like a bishop or knight. They do this not to win material right away, but to get a better position on the board.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

One famous example is from his game against Samuel Reshevsky in 1953 (see diagram). Petrosian, playing Black, was in a difficult spot. His pieces were stuck defending. He saw that White might attack his king's side. So, Petrosian came up with a plan to move his knight to a strong square in the center (d5). This would block White's pawns.

- 25... Re6!

By moving the rook, the black knight is now free to go to d5. From there, it can attack a pawn and help Black's pawns on the queen's side move forward. If White takes the rook with 26.Bxe6, then after 26...Qxe6, Black gets full control of the light squares. The knight will still go to d5, and Black will have a winning position.

- 26. a4 Ne7 27. Bxe6 fxe6 28. Qf1 Nd5 29. Rf3 Bd3 30. Rxd3 cxd3

The game eventually ended in a draw after 41 moves.

Contributions to Opening Theory

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Petrosian was an expert against the King's Indian Defence. He often played a specific set of moves that is now called the Petrosian System: 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.e4 d6 5.Nf3 0-0 6.Be2 e5 7.d5. This way of playing closes the center of the board early. One idea for White is to move their bishop to g5, which pins Black's knight to the queen. Black can respond by moving the queen or by playing ...h6, but h6 can make the king's side weaker.

The Queen's Indian Defence also has a variation developed by Petrosian: 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 b6 4.a3. The idea here is to stop Black from playing ...Bb4+. This system became very popular in 1980 when young Garry Kasparov used it to beat several grandmasters. Today, the Petrosian Variation is still considered a very strong way to play.

Other chess openings also have variations named after Petrosian. These include the Grünfeld Defence and the French Defence. There's also a variation in the Caro–Kann Defence named after him and former world champion Vassily Smyslov.

Quotes

- "In those years, it was easier to win the Soviet Championship than a game against 'Iron Tigran'." — Lev Polugaevsky

- "It is to Petrosian's advantage that his opponents never know when he is suddenly going to play like Mikhail Tal." — Boris Spassky

- "I'm absolutely convinced that in chess – although it remains a game – there is nothing accidental. And this is my credo. I like only those chess games, in which I have played in accordance with the position requirements... I believe only in logical and right game." — Tigran Petrosian

- "During tournament analysis sessions players all speak at once, but whenever Petrosian said anything, everyone would shut up and listen." — Yasser Seirawan

- "I associate Tigran Petrosian with Warne Marsh. A unique style of play which, it seemed, was too calm and dull, while in reality it was deep and cunning." — Levon Aronian

|

See also

In Spanish: Tigrán Petrosián para niños

In Spanish: Tigrán Petrosián para niños

- Chess in Armenia