Todor Zhivkov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Todor Zhivkov

|

|

|---|---|

| Тодор Живков | |

Zhivkov in 1971

|

|

| General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party (until 4 April 1981 as First Secretary) |

|

| In office 4 March 1954 – 10 November 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Valko Chervenkov |

| Succeeded by | Petar Mladenov |

| 1st Chairman of the State Council (until 12 June 1978 as President) |

|

| In office 7 July 1971 – 17 November 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Georgi Traykov (as Chairman of the Presidium of the National Assembly) |

| Succeeded by | Petar Mladenov |

| 36th Prime Minister of Bulgaria | |

| In office 19 November 1962 – 7 July 1971 |

|

| Preceded by | Anton Yugov |

| Succeeded by | Stanko Todorov |

| 48th Mayor of Sofia | |

| In office 27 May 1949 – 1 November 1949 |

|

| Preceded by | Anton Yugov |

| Succeeded by | Stanko Todorov |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Todor Hristov Zhivkov

7 September 1911 Pravets, Kingdom of Bulgaria |

| Died | 5 August 1998 (aged 86) Sofia, Bulgaria |

| Resting place | Central Sofia Cemetery |

| Political party | Bulgarian Communist Party (1932–1989) |

| Spouse |

Mara Maleeva-Zhivkova

(m. 1936; died 1971) |

| Children | Lyudmila, Vladimir |

| Signature |  |

Todor Hristov Zhivkov (Bulgarian: Тодор Христов Живков; 7 September 1911 – 5 August 1998) was a very important Bulgarian politician. He was the de facto (meaning "in practice") leader of Bulgaria from 1954 to 1989. He held the top position as General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party.

Zhivkov was one of the longest-serving leaders in the Eastern Bloc, a group of communist countries in Eastern Europe. He was also the longest-serving non-royal ruler in Bulgarian history. His time in power brought a lot of stability to Bulgaria. He worked closely with the Soviet Union but also tried to build connections with Western countries. He stayed in power for 35 years. His rule ended in 1989 when other leaders in his party pressured him to resign. This happened because of economic problems and growing public unhappiness. Soon after he left office, communist rule in Bulgaria ended.

Contents

Early Life and Political Beginnings

Todor Zhivkov was born in 1911 in a small Bulgarian village called Pravets. His family were farmers. The exact date of his birth was a bit of a family joke, but he believed it was September 7th.

In 1928, when he was 17, he joined the Bulgarian Communist Youth Union. This group was connected to the Bulgarian Workers Party, which later became the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP). He started working for the government's official publisher in Sofia the next year. In 1932, he officially joined the BCP. Even when the party was banned in 1934, Zhivkov kept his roles in its Sofia branch.

During World War II, Zhivkov was part of Bulgaria's resistance movement. This group fought against Bulgaria's alliance with Nazi Germany. He also showed support for the Jewish people in the country. In 1943, he helped organize a group of fighters called the Chavdar partisan detachment. He became a deputy commander for operations in the Sofia area in 1944. Many people who fought with him in Chavdar later became important figures in Bulgaria.

How Zhivkov Rose to Power

After September 9, 1944, Zhivkov became the head of the police force in Sofia. He was elected to the BCP's Central Committee in 1945 and became a full member in 1948. He was known for being a strong supporter of Stalin's ideas. In 1950, he joined the BCP's Politburo, which was the main decision-making body.

The April Plenum and Zhivkov's Leadership

After Joseph Stalin died, there was a shift towards shared leadership. In 1954, the then-leader, Valko Chervenkov, stepped down as General Secretary of the BCP. Zhivkov took his place. However, Chervenkov still had a lot of power as prime minister.

In 1956, after Nikita Khrushchev gave a famous speech criticizing Stalin, the BCP held a meeting. At this meeting, Zhivkov criticized Chervenkov for being too much like Stalin. Chervenkov was then moved from prime minister to a less powerful role. This is when Zhivkov truly became the main leader of Bulgaria. He started a policy of making things more open and less strict, similar to what was happening in the Soviet Union.

Starting to Make Changes

Zhivkov began to change things in Bulgaria, making the country more open and less focused on a "cult of personality" (where one leader is worshipped). He removed monuments and renamed places that were part of this cult. For example, "Mount Stalin" became Mount Musala again, and the city of "Stalin" returned to its old name, Varna. Zhivkov didn't want a cult around himself either. When people in his hometown of Pravets put up a statue of him, he thanked them but ordered it to be removed. It was only put back up after he passed away.

Zhivkov also stopped many harsh practices and reduced, but didn't completely end, forced labor. He pardoned and restored the rights of many people who he felt were unfairly punished. This included famous Bulgarian author Dimitar Talev.

These changes made many people hope for even more freedom. People started asking for more freedom of the press and cultural expression. Some even protested against local party leaders they didn't like. Zhivkov responded by firing and punishing those leaders. He then promoted younger, more ambitious people to take their places. This helped him gain more control over the Communist Party and also increased public support for his government.

In 1962, Zhivkov accused another important leader, Anton Yugov, of working against the party. Yugov was removed from the BCP and placed under house arrest.

An Attempted Coup

As Zhivkov's power grew, some former military leaders disagreed with his policies. In 1965, a group of high-ranking military officers planned to overthrow him. This event was called the "April Conspiracy" or the "Plot of Gorunia." Their goal was to create a new leadership that followed stricter communist ideas, similar to those in China. However, the plot was discovered, and most of the people involved were arrested and removed from the party.

Leading Bulgaria as Prime Minister and Chairman

As prime minister, Zhivkov remained loyal to the Soviet Union. But he also became more open than the leader before him. He allowed some market reforms, like letting farmers sell extra crops for profit. He also stopped the persecution of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

In the early 1970s, Zhivkov decided to update Bulgaria's constitution. This led to the creation of the "Zhivkov Constitution." This new constitution aimed to improve the country's image without causing instability. It separated the party and government roles. It gave more power to Bulgaria's National Assembly and allowed labor unions and youth groups to propose laws. It also created a "State Council" as a collective head of state. This council could make laws when the National Assembly was not meeting.

The new constitution also stated that political power would be shared between the Communist Party and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union. This was the communists' partner party. Bulgarian voters approved the new constitution in a referendum in 1971. After this, Zhivkov resigned as prime minister and became the Chairman of the State Council. This made him the official head of Bulgaria's collective presidency. Even though it looked like a two-party system, Zhivkov's Communist Party still had the most power.

How Zhivkov's Policies Shaped Bulgaria

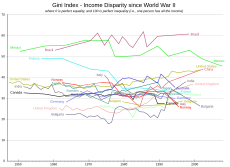

Economic Changes

In the mid-1950s, Bulgaria's economy, planned like the Soviet Union's, showed improvements. People's wages increased, and they ate more meat, fruit, and vegetables. More people had access to doctors. In 1957, farmers received the first pension system in Eastern Europe.

In 1959, the Communist Party launched a big economic plan. They wanted to double industrial production and triple farm production by 1962. They also combined many collective farms to make them more efficient. Zhivkov removed some rivals who criticized his economic plans. However, by 1960, he had to admit that the goals were too ambitious. There weren't enough skilled workers or materials. Harvests were bad in the early 1960s, and food prices went up, causing unhappiness in cities. Despite these problems, heavy industry grew, and food processing for export increased.

By the early 1960s, changes were needed for continued growth. In 1962, a new economic reform era began. They introduced the "New System of Management" in industry from 1964 to 1968. This system aimed to make businesses more responsible for their performance. Wages and bonuses were linked to profits. This led to good results for the pilot businesses.

However, by the late 1960s, Bulgaria started to move back towards a more traditional planned economy. This might have been due to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. But it also seemed that some party leaders were unhappy with the reforms' results. Despite this, Bulgaria made significant progress in science. They sent two cosmonauts into space and supplied 70% of all electronics in the Eastern Bloc.

In 1981, a new economic reform program, the New Economic Model (NEM), was introduced. It aimed to improve the supply of goods. However, it didn't greatly improve the quality or quantity of Bulgarian products. In the early 1980s, many high-quality goods were sent abroad to pay off Bulgaria's debt. This hurt technical progress and disappointed consumers. The NEM was not very successful.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev visited Bulgaria and encouraged Zhivkov to make the economy more competitive. This led to Bulgaria's own version of the Soviet "perestroika" program. In 1989, a new decree allowed "firms" to be the main economic units. It also allowed private citizens to hire up to ten people permanently. This last set of reforms confused the economy more than it helped.

Social Improvements

Under Zhivkov, Bulgaria made great progress in public health. Life expectancy increased, and infant mortality rates (deaths of babies under one year old) decreased significantly. By 1990, Bulgaria had the lowest infant mortality rate in Eastern Europe. The country also had many long-lived people. One of the first mass HIV-testing programs was started under Zhivkov.

People's incomes increased, especially for farmers. The availability of things like televisions, radios, refrigerators, washing machines, and cars greatly improved in the 1970s. Many of the cars were Soviet-made Fiats, some even built in Bulgaria.

Housing also improved with more and better homes being built. However, many homes were still small. Families often had to wait several years for an apartment, especially in Sofia. Priority was given to certain groups, like those who fought against fascism.

The education system remained largely the same, but in 1979, Zhivkov introduced a big reform. He created "Unified Secondary Polytechnical Schools." All students would receive the same general education, with a strong focus on technical subjects. In 1981, computers were introduced to most of these schools.

Foreign Relations

Zhivkov's government often sought closer ties with neighboring countries like Yugoslavia, Turkey, and Greece. However, old issues often prevented major improvements. Zhivkov always followed or supported the Soviet Union's foreign policies. This was because of strong historical and economic connections. In the 1970s and 1980s, Bulgaria improved its relations with countries outside the Soviet sphere. The 1970s were a time of close ties between the Soviet Union and Bulgaria. Zhivkov even received the "Hero of the Soviet Union" award in 1977.

Some people believed Zhivkov used the Soviet Union for Bulgaria's benefit. For example, Bulgaria would buy Soviet oil at low prices, process it, and then sell it on the world market for a large profit.

In 1963 and 1973, Zhivkov's government even asked if Bulgaria could become part of the Soviet Union. This was partly because they were worried about the Soviet Union making up with Yugoslavia, which Bulgaria had disagreements with.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Bulgaria also supported many national liberation movements around the world. This included countries like North Vietnam, Libya, and Angola. Bulgaria also sold weapons to other countries.

Bulgaria's relations with Western Europe and the United States were mostly decided by the Soviet Union's position. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, which Bulgaria strongly supported, it made relations with the West colder. There were also accusations of Bulgarian involvement in the attempted assassination of Pope John Paul II in 1981.

Relations with Greece, a traditional enemy, were stable in the 1970s and 1980s. Zhivkov wanted this stability to be a model for cooperation in the Balkans. In 1986, Bulgaria and Greece signed an agreement of friendship.

In 1988, Zhivkov met with a German delegation. He asked for ideas on how to reform Bulgaria's economy. He even asked about Bulgaria potentially joining the European Economic Community (EEC), which surprised the German leader. However, this discussion didn't lead to anything because the German leader died shortly after.

Cultural Developments

Zhivkov managed to prevent major unrest among Bulgarian intellectuals for a long time. Being a member of the writers' union brought many benefits. This encouraged many writers to join the officially approved group. However, it also meant they had to compromise their ideas. Zhivkov also brought back symbols of Bulgaria's cultural past. He encouraged people to remember "our motherland Bulgaria." In the late 1970s, he improved relations with the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

In 1980, Zhivkov appointed his daughter, Lyudmila Zhivkova, to a powerful position in science, culture, and art. Lyudmila became very popular by promoting Bulgaria's unique cultural heritage. She spent a lot of money to support scholars, collect Bulgarian art, and sponsor cultural institutions. She also encouraged closer cultural contact with the West. Her biggest project was the celebration of Bulgaria's 1,300th anniversary in 1981. When Lyudmila died in 1981, her work had successfully connected her father to Bulgarian national traditions.

Sports also thrived under Zhivkov's rule. From 1956 to 1988, Bulgaria won many Olympic medals and world competitions in sports like volleyball, rhythmic gymnastics, and wrestling.

Zhivkov's Personality

Zhivkov's way of speaking and sometimes rough manners made him the subject of many jokes in Bulgaria's cities. Even though the secret police were known to punish people for political jokes, Zhivkov himself was said to find them funny and even collected them. People often called him "bai Tosho" (meaning "Ol' Uncle Tosho") or "Tato" (a dialect word for "Dad").

The End of Zhivkov's Rule

Zhivkov had gained popularity by promoting Bulgarian national symbols, like those on the country's national emblem. This created a sense of national pride. However, in 1984, Zhivkov started a controversial policy called the "Revival Process." This policy aimed to make Bulgarian Turks change their names to Bulgarian ones. The government said it was to unite the country, but many Bulgarian Turks saw it as an attack on their identity.

Protests against this policy began in December 1984. Some protests turned violent, with clashes between demonstrators and police. Organized opposition groups formed, and some even took local officials hostage. The government responded with armed police and tanks.

The name-changing campaign ended after only a month, but the "Revival Process" continued. Some groups resorted to terrorism, setting off bombs in public places, causing deaths and injuries. The secret police reported finding many illegal pro-Turkish groups. In May 1989, Zhivkov announced that anyone who didn't feel at home in Bulgaria could leave for Turkey. He didn't expect so many people to leave, but over 360,000 people left the country. This campaign was a big failure and is seen as Zhivkov's biggest mistake. In 2012, the Bulgarian parliament condemned the "Revival Process" as a form of "ethnic cleansing."

This event marked the beginning of the end for Zhivkov. The international community strongly criticized Bulgaria, and even the Soviets were unhappy. Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet leader, decided Zhivkov had to go. Several high-ranking Bulgarian officials also started plotting to remove him.

In October 1989, the foreign minister invited a group of environmental activists to a conference in Sofia. Zhivkov ordered the police to beat up and arrest some of these activists. This caused international outrage. The plotters, including the defense minister, decided it was time for Zhivkov to leave.

On November 9, 1989, the defense minister told Zhivkov he needed to resign. Zhivkov was surprised and tried to get support, but couldn't. The next day, just before a meeting, Zhivkov was given an ultimatum: resign or be removed and possibly executed. Seeing he had no choice, Zhivkov resigned, officially due to age and health. A new leader, Petar Mladenov, was chosen. On November 17, the National Assembly removed Zhivkov from his position as Chairman of the State Council.

Within a month of Zhivkov's removal, the Communist Party gave up its guaranteed right to rule. By January 1990, the parts of the constitution that gave the Communist Party a monopoly on power were removed. The communist system Zhivkov had led for 33 years was gone.

After his removal, Zhivkov was criticized in parliament. In December, he was expelled from the party for "gross violations of laws and gross mistakes." The new leaders said he had left the country in a very bad state.

Trials and Later Life

After he lost power, Zhivkov faced five separate trials. These trials accused him of various things, including the "Revival Process," misusing public money, and human rights violations.

Zhivkov said he was not guilty of any of the charges. He was initially found guilty of one charge, misusing public funds for security services, and sentenced to seven years in prison. He appealed this decision. An appeals court confirmed the verdict but lowered his sentence to one year and six months. Zhivkov refused to ask for a pardon, saying pardons are only for guilty people, and he believed he was innocent.

In 1993, he was found innocent of human rights violations. In 1994, his sentence for misusing funds began, but he was placed under house arrest due to his poor health.

Zhivkov continued to insist on his innocence. In 1995, the Supreme Court of Bulgaria agreed to review his case. He threatened to go to the European Court of Human Rights if he wasn't found innocent. The prosecutor in his case even said there was "strong pressure" to find Zhivkov guilty.

On February 9, 1996, the Bulgarian Supreme Court ruled that the prosecution had not provided enough evidence for Zhivkov's guilt. They reversed the earlier verdict and declared him innocent of all charges.

Zhivkov was then released. He gave many interviews to foreign journalists and wrote his memoirs.

In his memoirs, he called himself an "ordinary village boy from Pravets." He described his life and shared his thoughts on his government. He believed that the socialist society in Bulgaria was good, but the "system" of government was too bureaucratic and failed. He thought the collapse of socialism was due to his own failures to reform the system. He still believed in socialism but thought a new, younger generation would lead to a "more prosperous, more just and more democratic Bulgaria."

In his last interview in 1997, he criticized the former members of his party who had taken state assets after he left. He blamed them for leading Bulgaria into economic ruin. He maintained that he still believed in socialism.

In early 1998, Zhivkov rejoined the Bulgarian Socialist Party. He died as a free man on August 5, 1998, at the age of 86, from pneumonia. After his death, all attempts to bring back the dismissed cases against him were dropped.

The government at the time refused his family's request for a state funeral. He was buried after a large private ceremony organized by the local Socialist Party.

Zhivkov's Legacy in Bulgaria

Public Image and Approval

Even years after his death, Zhivkov remains a part of Bulgarian pop culture. You can find songs, shirts, and souvenirs featuring him. In 2011, a billboard celebrating his 100th birthday was put up in Nesebar. His portraits and calendars are still common.

In 2001, a monument of Zhivkov from the communist era was put back up in his hometown of Pravets. His former home there was turned into a museum in 2002. Annual celebrations of his birthday have become a big event across the country. Since 2012, these celebrations have even included the flag of Europe.

Today, many Bulgarians view Zhivkov as popular and look back at his government with fondness. Surveys in the 2010s showed that his approval ratings were between 41% and 55%. One study found him to be among the top 5 most approved Bulgarian politicians ever. Another survey found that 74% of Bulgarians believe the country was "ruined" by politicians after his resignation. Half of those surveyed wished they could go back and live during "Zhivkov's time."

In 2019, some history textbooks in Bulgaria described Zhivkov as a "moderate ruler" who aimed to improve the lives of ordinary people. This caused some debate, with the education minister ordering the textbooks to be changed to condemn "bloody communism."

Political and Social Impact

Zhivkov managed to stay in power through many big events, like the split between China and the Soviet Union, and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

However, after he fell from power, the Soviet Bloc and the Soviet Union itself collapsed. The Communist Party in Bulgaria changed its name to the Bulgarian Socialist Party. This party won the first free elections in 1990. This was seen as a victory for socialism in Bulgaria. However, the Socialist government struggled to solve the country's problems. It eventually collapsed, and the opposition party won the next election.

Zhivkov's attempts to force Bulgarian Turks to change their names did not work. Instead, it led to the creation of the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, a party for ethnic Turks. Even though Bulgaria's new constitution limited parties based on ethnicity, this party was ruled legal in 1992.

So, many of Bulgaria's political ideas and foreign policies from Zhivkov's time have now been reversed.

Economic Legacy

After facing difficulties in the 1940s and 1950s, Bulgaria's economy grew quickly from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s. Many of today's large factories and industrial sites were built under Zhivkov. Bulgaria's nuclear power station was built in the 1970s, making the country a major exporter of electricity.

By the 1970s, Bulgaria focused on high technologies like electronics and even space exploration. In 1979, Bulgaria launched its first cosmonaut into space. The country was also one of the first to sell electronic calculators and digital watches. In 1982, Bulgaria launched its own personal computer, the "Pravets." Mass tourism also grew under Zhivkov's leadership starting in the early 1960s.

However, Bulgaria's economy relied heavily on the Soviet Union. After the Soviet oil price shock in 1979, the economy went into a severe recession. After the Soviet markets disappeared in the early 1990s, Bulgaria's economy struggled. Many of the industrial facilities built under Zhivkov were not attractive to investors and fell into disrepair. Many skilled workers retired, left, or moved to private jobs.

It is widely believed that poor and corrupt management after 1989 had a much bigger impact on the economy's decline. State properties were often misused, and money was sent to tax havens. This created a new class of wealthy individuals but destroyed much of Bulgaria's industry.

Family and Personal Life

Zhivkov married Mara Maleeva in 1938. They had two children, a daughter named Lyudmila Zhivkova and a son named Vladimir. Mara Maleeva was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1969 and died in 1971. Her death deeply affected Zhivkov.

Lyudmila became a notable cultural figure. She promoted unusual artistic ideas and was interested in Eastern religions. Her mother had not wanted her to be involved in politics. But after her mother's death, Zhivkov appointed Lyudmila to a role in cultural diplomacy. She actively promoted cultural openness and spent a lot of money supporting artists and cultural institutions. She also encouraged cultural contact with the West. Lyudmila died suddenly in 1981 at the age of 38.

Zhivkov's son-in-law, Ivan Slavkov, became the head of Bulgaria's state television company. He later became president of the Bulgarian Olympic Committee.

Zhivkov had a special connection to his birthplace, Pravets. In the 1960s, this small village became a town. In 1982, Bulgaria's first personal computer was named "Pravets." The people of Pravets put up a statue of Zhivkov, but he had it taken down to prevent a personality cult. It was put back up after his death.

Images for kids

-

Todor Zhivkov and Georgi Dimitrov in a Fatherland Front congress in 1946.

See also

In Spanish: Todor Zhivkov para niños

In Spanish: Todor Zhivkov para niños