Georgi Dimitrov facts for kids

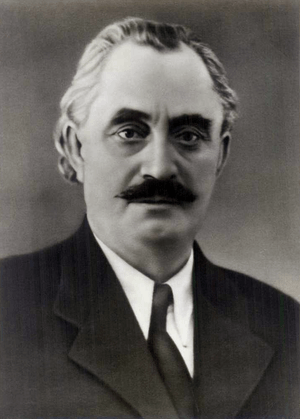

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (Bulgarian: Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (Russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian politician who believed in communism. He became the first communist leader of Bulgaria, serving from 1946 to 1949. Dimitrov also led an important international communist organization called the Communist International (Comintern) from 1935 to 1943.

Quick facts for kids

Georgi Dimitrov

|

|

|---|---|

| Георги Димитров | |

|

|

| General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party | |

| In office 27 December 1948 – 2 July 1949 |

|

| Succeeded by | Valko Chervenkov |

| 32nd Prime Minister of Bulgaria 2nd Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Bulgaria |

|

| In office 23 November 1946 – 2 July 1949 |

|

| Preceded by | Kimon Georgiev |

| Succeeded by | Vasil Kolarov |

| Head of the International Policy Department of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 27 December 1943 – 29 December 1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Suslov |

| General Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Communist International | |

| In office 1935–1943 |

|

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov

(Bulgarian: Георги Димитров Михайлов) 18 June 1882 Kovachevtsi, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Died | 2 July 1949 (aged 67) Barvikha, RSFSR, USSR |

| Political party | BCP |

| Other political affiliations |

BRSDP (1902–1903) BSDWP-Narrow Socialists (1903–1919) |

| Spouses | Ljubica Ivošević (1906–1933) Roza Yulievna (until 1949) |

| Profession | typesetter, revolutionary, politician |

Contents

Early Life and Activism

Dimitrov was born in Kovachevtsi, a village in what is now Pernik Province, Bulgaria. He was the first of eight children. His parents were refugees from Ottoman Macedonia. His father was a craftsman who later became a factory worker. His mother was a Protestant Christian.

His mother wanted him to become a pastor and sent him to Sunday school. However, he was expelled at age 12. He then trained as a typesetter, which is someone who arranges text for printing. From a young age, he became involved in the labor movement in Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. By age 15, he was an active member of a trade union. In 1900, he became the secretary of the printers' union in Sofia.

Political Career

Dimitrov joined the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers' Party in 1902. In 1903, he followed Dimitar Blagoev and his group, which formed the Social Democratic Labour Party of Bulgaria. This party was sometimes called "The Narrow Party." In 1919, this party became the Bulgarian Communist Party and joined the Comintern, an international organization for communist parties.

From 1904 to 1923, Dimitrov served as the Secretary of the General Trade Unions Federation. This organization was controlled by the "Narrow Party."

Early Challenges

In 1911, Dimitrov spent a month in prison. He was accused of speaking falsely about an official from a rival trade union. In 1915, during World War I, he was elected to the Bulgarian Parliament. He spoke out against the decision to approve new money for the war. In 1917, he was charged with encouraging soldiers to rebel. He lost his protection as a member of parliament and was imprisoned. He was released in 1919.

After his release, he went into hiding and tried to visit Russia. He finally reached Moscow in February 1921. He returned to Bulgaria later that year. In December 1922, he was elected to the executive committee of Profintern, an international communist trade union.

Uprising and Exile

In June 1923, the Prime Minister of Bulgaria, Aleksandar Stamboliyski, was removed from power in a coup. Dimitrov and other communist leaders initially decided not to take sides. However, the Comintern criticized this decision.

After another communist leader, Vasil Kolarov, came from Moscow, Dimitrov accepted the Comintern's view. In September 1923, Dimitrov and Kolarov led an uprising against the new government. This uprising failed, and many communist supporters lost their lives. Despite its failure, the Comintern approved the attempt. Dimitrov and Kolarov escaped to Vienna and became the joint leaders of the Bulgarian Communist Party.

In 1926, Dimitrov was put on trial in Bulgaria without being present. He was sentenced to death. His brother, Todor, was arrested and died in 1925. Dimitrov lived in the Soviet Union under different names until 1929. He then moved to Germany and became in charge of the Comintern's Central European section. In 1932, he was appointed Secretary General of the World Committee Against War and Fascism. This committee worked to oppose war and fascism.

The Leipzig Trial

Dimitrov was living in Berlin when the Nazis came to power in Germany. On March 9, 1933, he was arrested. He was accused of being involved in setting the Reichstag building on fire. This building housed the German Parliament.

During the Leipzig trial, Dimitrov chose to defend himself instead of using a lawyer. He used the trial to speak out against his Nazi accusers, especially Hermann Göring. His calm and strong defense gained him worldwide attention. Many people admired his courage. The Milwaukee Journal newspaper wrote that Dimitrov showed "the most magnificent exhibition of moral courage." A popular saying in Europe was: "There is only one brave man in Germany, and he is a Bulgarian."

Dimitrov and two other Bulgarians were found not guilty. Two months later, in December 1933, the Soviet Union helped them gain Soviet citizenship and be released.

Leading the Comintern

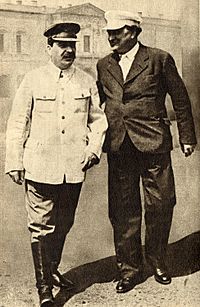

When Dimitrov arrived in Moscow in February 1934, Joseph Stalin encouraged him to change the Comintern's approach. Stalin wanted Dimitrov to focus on uniting different groups against fascism. Dimitrov's fame from the Leipzig Trial grew. In April, he was appointed to the Comintern's executive committee. He was chosen by Stalin to become the head of the Comintern in 1934. He became a close advisor to Stalin.

In July–August 1935, Dimitrov was the main figure at the 7th Comintern Congress. He was elected General Secretary of the Comintern at this meeting.

Leader of Bulgaria

In 1946, after 22 years away, Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria. He became the leader of the Communist party there. After the People's Republic of Bulgaria was established in 1946, Dimitrov became the Prime Minister of Bulgaria. He also kept his Soviet Union citizenship.

Balkan Federation Idea

Dimitrov began discussions with Josip Broz Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia. They talked about creating a federation of Southern Slavs. This idea had been discussed between Bulgarian and Yugoslav communist leaders since 1944. The goal was to unite Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, seeing them as the main homelands of Southern Slavs.

This led to the 1947 Bled accord, signed by Dimitrov and Tito. This agreement aimed to remove border controls and plan for a future customs union. Yugoslavia also agreed to forgive Bulgaria's war reparations. The initial plan for the federation included joining the Blagoevgrad Region of Bulgaria with the People's Republic of Macedonia. It also involved returning the Western Outlands from Serbia to Bulgaria. Bulgaria even allowed teachers from Yugoslavia to teach the Macedonian language in schools in the Blagoevgrad Region.

Differences and Fallout

However, differences soon appeared between Tito and Dimitrov. They disagreed on how the new country would be structured and on the "Macedonian question." Dimitrov imagined a state where Bulgaria and Yugoslavia would be equal. Tito, however, saw Bulgaria as a new republic within a larger Yugoslavia, controlled from Belgrade. They also disagreed on the identity of the Macedonians. Dimitrov thought they were a branch of Bulgarians, while Tito saw them as a separate nation. Bulgaria's initial acceptance of Macedonian identity in the Blagoevgrad Region slowly turned into concern.

By January 1948, Tito's plans to include Bulgaria and Albania became a problem for the Cominform and other Eastern Bloc countries. In December 1947, Dimitrov met with Albanian leaders. He advised them to keep their party strong and revolutionary.

After some disagreements, Stalin invited Tito and Dimitrov to Moscow. Dimitrov accepted, but Tito sent his associate, Edvard Kardelj. The disagreement between Stalin and Tito in 1948 gave the Bulgarian government a chance to criticize Yugoslavia's policy on Macedonia. The ideas of a Balkan Federation and a United Macedonia were dropped. Macedonian teachers were sent away, and the teaching of the Macedonian language in the region stopped. At a party congress, Dimitrov accused Tito of "nationalism" and being against international communist ideas. Despite this, Yugoslavia still kept its promise to forgive Bulgaria's war reparations from the 1947 Bled accord.

Personal Life

In 1906, Dimitrov married his first wife, Ljubica Ivošević, a writer and socialist from Serbia. They were together until her death in 1933. While in the Soviet Union, Dimitrov married his second wife, Roza Yulievna Fleishmann. They had one son, Mitya, born in 1936, who sadly died at age seven from diphtheria. Dimitrov also adopted two other children: Fani, the daughter of Wang Ming, and Boiko Dimitrov, born in 1941.

Death

Dimitrov died on July 2, 1949, at a sanatorium near Moscow. There has been some talk that he might have been poisoned, as his health declined quickly. However, this has never been proven. Some believe that Stalin did not like Dimitrov's idea of a "Balkan Federation" or his close relationship with Tito.

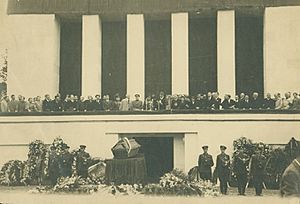

After his funeral, Dimitrov's body was preserved and put on display in a special building called the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum in Sofia, Bulgaria. After communism ended in Bulgaria, his body was buried in Sofia's central cemetery in 1990. His mausoleum was taken down in 1999.

Legacy

Many places were named after Georgi Dimitrov.

Bulgaria

- Dimitrovgrad, Bulgaria

- Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum (1949–1999)

Russia

- Dimitrovgrad, Russia

- In Novosibirsk, a large street and a bridge over the Ob River are named after him. The bridge opened in 1978.

Serbia

- Dimitrovgrad, Serbia

Romania

- In Bucharest, a boulevard was named after him (Bulevardul Dimitrov). After 1990, its name was changed to Ferdinand (Bulevardul Ferdinand), after a former Romanian king.

Armenia

- Dimitrov, Armenia

Hungary

- The Fővám tér square and the Máriaremetei út street in Budapest, Hungary were named after Dimitrov between 1949 and 1991. A statue of him was put up in 1954 and later moved. Both sculptures are now in the Memento Park.

Slovakia

- During communist rule, a chemical factory in Bratislava was named "Chemické závody Juraja Dimitrova" (Dimitrovka). After the Velvet Revolution, it was renamed Istrochem.

East Germany

- In East Berlin's Pankow district, a street called Danziger Straße was renamed Dimitroffstraße (Dimitrov Street) in 1950. An U-Bahn (subway) station was also named after him. After Germany reunited, the street's name was changed back to Danziger Straße in 1995, and the U-Bahn station was renamed Eberswalder Straße.

Benin

- A large painted statue of Dimitrov still stands in the center of Place Bulgarie in Cotonou, Republic of Benin. This is decades after the country moved away from Marxism–Leninism.

Ukraine

- Dymytrov, now Myrnohrad in Ukraine, was named Dymytrov between 1972 and 2016.

Yugoslavia

- After the 1963 Skopje earthquake, Bulgaria helped rebuild by donating money for a high school. It opened in 1964 and was named after Georgi Dimitrov to honor Bulgaria's first post-World War II president. It still has that name today.

- The town of Caribrod (Цариброд) in what was then Serbia was renamed Dimitrovgrad (Димитровград) in 1950. This was to honor the Bulgarian leader, even after the Tito-Stalin split. The name is still used, though some people prefer the older name.

Cuba

- A main avenue in the Nuevo Holguin neighborhood of Holguín, Cuba is named after him. This neighborhood was built in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias Jorge Dimitrov in Bayamo is named after him.

- IPUEC Jorge Dimitrov (Ceiba 7) school in Caimito

- Primary School Escuela Primaria Jorge Dimitrov in Havana

Nicaragua

- The Sandinista government of Nicaragua renamed one of Managua's central neighborhoods "Barrio Jorge Dimitrov" in his honor during the country's revolution in the 1980s.

Cambodia

- There is also an avenue (#114) named for him in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Italy

- There is a Georgi Dimitrov street in the city of Reggio Emilia, Emilia Romagna region.

Works

See also

In Spanish: Gueorgui Dimitrov para niños

In Spanish: Gueorgui Dimitrov para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |