Vale Royal Abbey facts for kids

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The abbey church of St Mary the Virgin, St Nicholas, and St Nicasius, Vale Royal |

| Other names | Vale Royal Abbey |

| Order | Cistercian |

| Established | 1270/1277 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Mother house | Dore Abbey |

| Dedicated to | Virgin Mary, St Nicholas, St Nicasius |

| Diocese | Diocese of Lichfield |

| Controlled churches | Frodsham, Weaverham, Ashbourne, Castleton, St Padarn's Church, Llanbadarn Fawr |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Edward I |

| Important associated figures | Edward I, Thomas Holcroft |

| Site | |

| Location | Whitegate, Cheshire, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°13′29″N 2°32′33″W / 53.2247°N 2.5426°W |

| Visible remains | Foundations of the church, surviving rooms within later house, earthworks. Gate chapel survives as parish church |

| Public access | None |

Vale Royal Abbey was once a large monastery in Whitegate, England. It was built for Cistercian monks during the Middle Ages. Later, it became a grand country house. Today, it's hard to see exactly where the original abbey stood.

The abbey was started around 1270 by Lord Edward, who later became King Edward I. He supposedly made a promise to build it after a scary sea journey. Building was delayed until 1272 because of civil wars. The first location at Darnhall wasn't good, so the abbey was moved a few miles north to Delamere Forest.

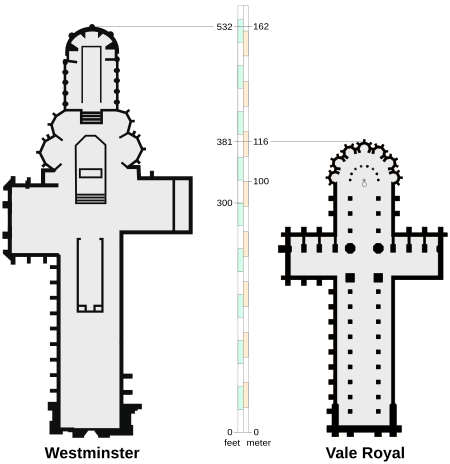

King Edward wanted Vale Royal Abbey to be huge. If it had been finished, it would have been the biggest Cistercian monastery in England. But the king often had money problems, which stopped the work.

During construction, England went to war with Wales. This meant the king needed money for his army, so Vale Royal lost its funding and skilled builders. When work started again, the abbey had to be much smaller. The abbey also had problems with its management and with local people, which sometimes led to fights.

Vale Royal Abbey was closed in 1538 by King Henry VIII. This was part of his plan called the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The abbey's lands were sold to Thomas Holcroft. He tore down most of the abbey, including the church. But he used some of the old buildings, like parts of the cloister, to build his new mansion in the 1540s.

The mansion was changed and made bigger over many years. In the early 1600s, the Cholmondeley family took over Vale Royal. It stayed their family home for more than 300 years. After World War II, the house was sold and became a private golf club. Today, the building is still used and has parts of the medieval abbey inside, like the dining hall and kitchen.

Contents

Starting the Abbey

Vale Royal Abbey was first planned at Darnhall by Lord Edward, before he became King Edward I. The abbey's own history book says that Edward was caught in a bad storm at sea in the 1260s. He and his crew were very scared. Edward prayed to the Virgin Mary and promised to build an abbey in her name if they were saved. The story says the storm stopped right away, and they landed safely. As soon as Edward left his ship, the storm returned and destroyed it.

However, this story doesn't quite match what we know about Edward's travels. He went on a crusade in 1270 and didn't return until 1272, after his father died. By then, the abbey's first official document was already written. Historians think Edward might have founded the abbey to ask for Mary's protection during his crusade, rather than for a past event.

The political situation in England, with civil wars, delayed the abbey's construction. After the rebels were defeated in 1265, plans for the Cistercian monastery at Darnhall in Cheshire moved forward. The abbey was to be paid for with land that now belonged to the king. In 1270, Edward gave more land and churches to his new abbey.

Moving the Abbey Site

Building the abbey was difficult. The first monks arrived at Darnhall in 1274 from Dore Abbey, their "motherhouse." Local people were angry because the abbey's new lands affected their way of life. The abbey had rights to Darnhall Forest, where villagers used to roam freely.

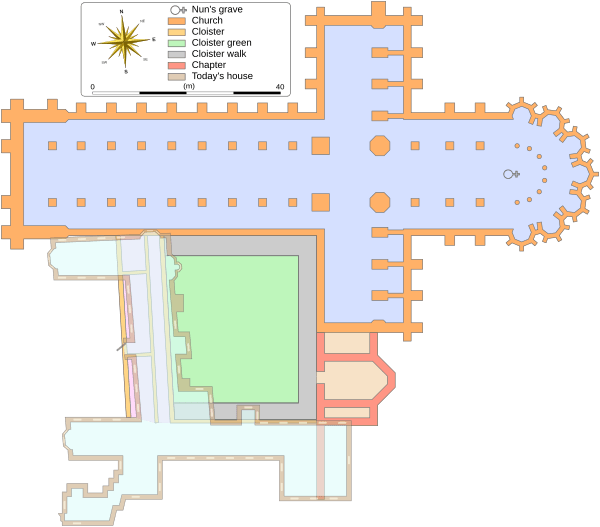

The Darnhall site was also not good for a large building. It might have been meant as a temporary spot. In 1276, King Edward agreed to move the abbey to a better place. A new site was chosen in Over, near the Forest of Mondrem. On August 13, 1277, the king, Queen Eleanor, and their son Alphonso laid the foundation stones for the new abbey's main altar. The monks moved to temporary homes at Vale Royal in 1281 while the abbey was being built. Vale Royal was meant to be the largest and most detailed Cistercian church in Christian Europe.

The exact location of the abbey is hard to pinpoint today. It was mostly within the monks' land called Conersley, which was later renamed Vale Royal. The whole area was about 400 acres (160 hectares).

Building the Abbey

In 1958, during an excavation, the abbey site was described as being on the left bank of the River Weaver, southwest of Northwich. It was on flat ground that sloped down to the river, which helped with drainage.

King Edward had big plans for Vale Royal. He wanted it to be a very important abbey, bigger and more beautiful than any other Cistercian house in Britain. It was also meant to show off the wealth and power of the English monarchy and Edward's own faith. He wanted it to be grander than his grandfather King John's abbey at Beaulieu. The project was similar to his father's Westminster Abbey. Edward may have even planned to be buried at Vale Royal. This was his biggest act of faith; he didn't fund any other monasteries.

The building plans were very detailed. Fifty-one masons (skilled stoneworkers) from all over the country were hired. The main architect was Walter of Hereford, one of the best of his time. He was paid well and worked on the abbey from 1277 to 1290. Work began on a huge, detailed High Gothic church, almost the size of a cathedral.

The abbey was planned to be 116 meters (381 feet) long with a central tower. The east end was rounded with 13 chapels. South of the church was a cloister (a covered walkway) 42 meters (138 feet) square, surrounded by other buildings. From 1278 to 1280, John of Battle was the undermaster of the works. He later built the King's memorial crosses for Queen Eleanor.

From 1277 to 1281, 35,000 cartloads of stone were brought from quarries nine miles away. Timber came from local forests to build workshops and homes for the workers and monks. About £3,000 was spent on construction in these four years. In 1283, £1,000 was set aside each year for building, taken directly from the King's money. The King put his clerk, Leonius, in charge of the money.

In the early 1280s, the king gave more land and money. Work went quickly. In 1283, the new church was consecrated (made sacred) by the Bishop of Durham. Edward and his court attended. The King even gave the abbey a piece of the True Cross that he had captured on his crusade. In 1287, marble columns for the cloister were ordered from the Isle of Purbeck.

Money Troubles

The abbey's money problems started soon after. In the 1280s, the royal finances ran low. War with Wales broke out in 1282, and Edward needed money for soldiers and to build castles. He took money that was meant for Vale Royal and its workers. This happened around the time the monks' cloister was being built. The monks were still living in temporary homes.

In 1290, Edward announced he was no longer interested in the abbey. The reasons are not fully known. Historians think the monks might have upset him, or it could be linked to Queen Eleanor's death that year. Edward was known for suddenly stopping funds for his religious projects. It's also possible some building money was used for other things without the King's permission.

Royal grants became very small. The abbey also didn't receive money it was owed, like a legacy from Queen Eleanor's will. By 1291, they owed £1,808. The King paid £808, but the rest wasn't paid until 1312, after Edward's death.

The monks struggled to finish the huge project without royal help. Even though they had income from their own lands, the abbey owed a lot of money to other churches, royal officials, and builders. Work stopped for at least ten years after 1290. When it started again, it was on a much smaller scale.

When Edward II became king in 1307, some money arrived. But this only lasted five years.

Problems with Local People

Besides money troubles, Vale Royal faced other serious issues. Like any landlord, a religious house depended on income from its lands. Monasteries often tried to control their tenants more strictly. From its start, Vale Royal had problems with its tenants and neighbors.

The abbey was disliked by people in Darnhall and Over. They found themselves under the abbey's feudal lordship, which meant they were no longer free tenants. The dispute was mainly about forestry rights. The abbey was in the Forest of Mondrem, which had been mostly common land. The abbey gained special rights, which locals felt took away their livelihoods.

Abbots were also feudal lords and could be strict. The villagers fought back, sometimes in court and sometimes with violence. The villagers of Darnhall and Over had probably been used to more freedom under previous landlords.

Abbey's Wealth and Income

The village of Over was the center of the abbey's lands. It was under the abbot's feudal lordship. The abbey's first endowment included the Delamere Forest site and lands in Darnhall. They also received rights to churches in Frodsham, Weaverham, and Ashbourne. More land grants came later, including estates on the Wirral.

The abbey also had a glassmaking forge in Delamere Forest. It made a small profit for a few decades but stopped around 1309.

Wool exports were the abbey's main source of income. Cistercian monks were known for producing wool. In 1283, the abbot received money in advance for wool that the abbey would deliver.

In the mid-1330s, Abbot Peter calculated the abbey's income was about £248. A lot of this money was spent on hospitality (welcoming guests), wages for staff, and the abbot's own expenses. There was not enough left for the monks' daily needs. By 1342, the abbey was in debt. A fire had also burned down their farm buildings at Bradford and Hefferston, destroying all their corn. The monks had to buy food until the next harvest.

Vale Royal's finances seemed to get better by the 1400s. Taxes in 1509 and 1535 showed the abbey's income had increased. Expenses were also down. Although the abbey was rich in goods, it had fewer monks than planned. In 1509, a visitor found only fifteen monks instead of the thirty that were expected.

Later Years of the Abbey

Even with money problems, building continued slowly. By 1330, the monks could move into their main living quarters. The east end of the church was finished, and enough of the cloister buildings were done to make the abbey livable. But much of the main roof was still open to the weather.

Royal funding had almost stopped. In 1336, Abbot Peter complained that the main vaults, cloisters, chapter house, and dormitories still needed to be built. He said their income was not enough to finish the huge church.

In 1353, there was new hope. Edward the Black Prince, son of King Edward III and now Earl of Chester, was very involved in his father's wars in France. He gave a lot of money to the county's important families and institutions, including Vale Royal. He wanted the abbey finished. He gave 500 marks (a type of money) right away and another 500 five years later when he visited. In 1359, Prince Edward gave Vale Royal the church of Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion to help pay for construction.

William Helpeston was hired to oversee construction in August 1359. He was paid wages, and the abbey provided food and lodging for him and his men. This work was expected to take six years. The abbey choir was finished in the first year.

However, a great storm on October 19, 1359, destroyed much of the nave (the main part of the church). The new lead roof and the unfinished arches collapsed. There were no signs of poor building, so it was just a very strong storm.

Repairs were made slowly over the next thirteen years. The church was rebuilt to be smaller than before. The Black Prince died in 1376, and the monks knew that royal gifts would stop. Work continued on a smaller scale into the reign of Richard II, who supported the abbey a little because it was a royal foundation. The King was happy that the abbey was smaller and cost less.

Repairs and building continued off and on into the 1400s. An aisle was added to the church in 1422. Not much else is known about the abbey until the 1500s, during the time of King Henry VIII.

Relations with Local Gentry

The abbey's relationships with the local gentry (wealthy landowners) were also difficult. The abbey was often involved in disputes with powerful local families, which sometimes led to violence.

Choosing a New Abbot

Abbot John Butler died in the summer of 1535. The election of his replacement shows how much local gentry tried to control the abbey's affairs. William Brereton and Piers Dutton, two powerful local knights, each wanted their own candidate to become abbot.

The election was full of corruption. Dutton's candidate, for example, offered Thomas Cromwell, King Henry VIII's chief minister, £100. Even the church visitor, Thomas Legh, who was supposed to be fair, accepted a bribe. Queen Anne Boleyn also favored a candidate. In the end, King Henry ordered a free election, and John Hareware was chosen. Even though his candidate lost, Brereton still managed to get a yearly payment of £20 from the new abbot for the rest of his life.

Cromwell was appointed steward of the abbey by the King. Knowing that monasteries might soon be closed, Abbot Hareware started raising money quickly. He did this by renting out abbey lands for very low rents but with high upfront fees.

The Abbey Closes Down

By 1535, Vale Royal was one of only six monasteries left in Cheshire. That year, it was reported to have an income of £540, making it the wealthiest of the Cistercian monasteries founded in the 1200s. Much of this money was used to bribe local gentry and pay them pensions. Because it was so wealthy, Vale Royal avoided being closed down by King Henry VIII's first act against monasteries. At this time, its monk population had dropped to 15.

Abbot John Hareware tried two things: to save the abbey and to make sure he and his monks would be safe if it closed. He bribed powerful people like Thomas Cromwell with money and property. He also leased most of the abbey's lands to friends to keep them out of the King's hands if the abbey fell. Many of these leases would be canceled if the abbey survived. Hareware also sold other abbey assets, like animals and timber, for cash.

The closing of Vale Royal started in September 1538 by Thomas Holcroft, a royal official. Holcroft claimed the abbey had given up its rights to him on September 7, probably with a fake signature. The abbot and monks denied this. Holcroft then accused the abbot of trying to take over the abbey himself. The monks kept asking the government for help. Abbot John wrote to Thomas Cromwell, saying he and his monks had never agreed to give up their monastery.

In December 1538, Abbot John and his monks were allowed to join another religious order. To make sure the abbey's surrender was legal, a special court was held at the abbey on March 31, 1539, with Cromwell as judge. Instead of looking into the surrender, the court accused the abbot of treason. The abbot was found guilty, and Vale Royal was given to the crown. However, Abbot John was not executed. He was given a large yearly payment of £60 and the abbey's silver, which suggests the trial was a way to make him agree to the closure. The other monks also received payments. The abbey's lands became part of the new parish of Whitegate.

After the Abbey Closed

After long talks with the king, Thomas Holcroft leased Vale Royal. This made him a very important man. In 1539, he tore down the church. On March 7, 1544, the King confirmed Holcroft's ownership, giving him the abbey and its lands for £450. Holcroft removed many of the abbey's buildings. He kept the south and west cloister areas, including the abbot's house, the monks' dining hall, and kitchen. These became the center of his new mansion.

Holcroft's family lived at Vale Royal until 1615. During their time, new windows were added to the mansion. In 1615, the Cholmondeley family took over the house. Mary Cholmondeley, a wealthy widow, bought the abbey as her home. In August 1617, she hosted King James I and a deer-hunting party at Vale Royal. The king enjoyed himself so much that he knighted two family members. He offered to help Mary's sons in their careers, but she refused so strongly that the King called her "the Bolde Lady of Cheshire." Mary gave the abbey to her fourth son, Thomas, when she died in 1625.

During the English Civil War, the Cholmondeley family supported King Charles I. This had serious results. Fighting happened at Vale Royal, the house was robbed, and the south wing was burned down by Parliamentarian forces.

Despite this, the Cholmondeley family continued to live in the abbey. A new wing was added in 1833. In 1860, Hugh Cholmondeley, Baron Delamere hired architect John Douglas to redesign the center of the south side. Douglas added another wing and changed the dining room. The church of St Mary, which was outside the abbey gates, was largely rebuilt in 1728 and again in 1874–1875.

The Cholmondeley family lived in the abbey for over 300 years. In 1907, they rented it to a rich businessman, Robert Dempster. His daughter, Edith, lived at Vale Royal with her father. Edith later inherited half of his money and the lease on Vale Royal. She eventually gave up the lease and bought the Sutton Hoo estate, where she later discovered a very rich Anglo-Saxon burial ground.

Another Cholmondeley, Thomas, Baron Delamere, moved into the abbey in 1934. He was forced out in 1939 when the government took over Vale Royal to use as a hospital for soldiers during World War II. The Cholmondeleys got the abbey back after the war but sold it in 1947 to Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). ICI used it for staff housing and later as headquarters for its salt division. In 1958, ICI allowed and helped with an archaeological excavation.

ICI moved out in 1961. There were ideas to use the abbey as a health center, a country club, a school, or a prison. In 1977, it became a care home for people with learning disabilities. In 1998, Vale Royal became a private golf club. A plan to turn the house into apartments led to a detailed archaeological study in 1998.

Finding Abbey Remains

Nothing remains of the great church, and almost nothing of the other abbey buildings. However, archaeological work has shown many details of the church's structure. Excavations in 1911–1912 found that the church was 421 feet (128 meters) long, with a decorated floor in its 92-foot (28-meter) nave.

Much of the abbey's stonework was sold after it was destroyed. Some was used to build a well. Abbey stones were found in the walls of other houses. The ceiling of Weaverham church's north aisle might have come from Vale Royal. The south wing of the current house includes the original dining hall roof, which dates back to the late 1400s. The 1958 excavation uncovered parts of the 1359 additions, including the rounded east end. Pieces of stained glass and other architectural fragments were also found.

A circular stone monument, called the Nun's Grave, is said to honor Sister Ida. She was a 14th-century nun who supposedly cared for an abbot of Vale Royal. The monument was put up by the Cholmondeley family. It uses parts from an old medieval cross and a pillar base. The current country house includes parts of the original abbey, like a door arch. In 1992, old medieval graffiti was found scratched into plaster on an internal wall.

The building is a Grade II* listed building, meaning it's a very important historic building. St Mary's church is listed at Grade II, and what's left of Vale Royal Abbey is a scheduled ancient monument.

See also

- Abbot of Vale Royal

- Grade II* listed buildings in Cheshire West and Chester

- Listed buildings in Whitegate and Marton

- List of houses and associated buildings by John Douglas

- Round Tower Lodge

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |