St Padarn's Church, Llanbadarn Fawr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Padarn's Church |

|

|---|---|

|

Eglwys Sant Padarn

|

|

St Padarn's Church

|

|

| OS grid reference | SN 599 809 |

| Location | Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| Previous denomination | Catholic |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Padarn |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building (9832) |

| Designated | 21 January 1964 |

| Years built | 1257 |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Llanbadarn Fawr and Elerch and Penrhyncoch and Capel Bangor |

| Deanery | Llanbadarn Fawr |

| Archdeaconry | Cardigan |

| Diocese | Diocese of St David's |

Saint Padarn's Church is a very old parish church in Llanbadarn Fawr, near Aberystwyth, in Ceredigion, Wales. It belongs to the Church in Wales. It is the largest mediaeval (Middle Ages) church in mid-Wales.

This church has a long history, starting in the early 500s. It has been many things: a Welsh monastic center (called a clas), a Benedictine priory, and a royal church. Since 1538, it has been a parish church led by a vicar.

Contents

- History of St Padarn's Church

- How the Church Started in the 500s

- Who Was Saint Padarn?

- The Church as a Learning Center

- Sulien and His Family's Influence

- Norman Influence and Changes

- A Short Time as a Priory

- The Church's Decline and Royal Control

- Later Middle Ages and New Control

- Chancel Extension and Monastery Closures

- Later Life as a Parish Church

- The Church Today

- Organ

- Architecture of St Padarn's Church

- Churchyard

History of St Padarn's Church

The land where St Padarn's Church stands has been used for Christian worship since the early 500s. It was likely started by Saint Padarn, who the church is named after. We don't have many old records or archaeological finds from this very early time. So, much of the church's first history is based on guesses rather than solid facts.

How the Church Started in the 500s

We don't know the exact year Saint Padarn founded the church. But it's clear that Llanbadarn Fawr began in the early 500s as a Celtic clas church. A clas was a type of early Christian settlement, often with a group of religious people. It was not a cathedral like we think of today. Llanbadarn Fawr was one of the most important clasau in early Christian Wales. It was also a key place for writing and learning.

Who Was Saint Padarn?

Very little is known for sure about Saint Padarn (also called Paternus). The first written mention of him was around 1097. We can only guess at the general outline of his life.

Like many people in Europe during the early Middle Ages, he was called a saint after he died. In the 1100s, people decided to write a Vita or Latin Life about him. These "Lives" were not like modern biographies. They were hagiographies, stories meant to show the saint as a holy person who performed miracles.

Tradition says Padarn came from Brittany, a region in France. But he might have been from south-east Wales. He was said to be both an abbot (leader of a monastery) and a bishop for many years. From his base at Llanbadarn Fawr (which means "great church of St Padarn"), he spread Christian teachings to the nearby areas.

The Vita Sancti Paternus tells many supposed details of his life. He might have been connected to Roman-British civilization. His churches seem to be linked by Roman roads. Llanbadarn Fawr is thought to be near where the Roman road called Sarn Helen crosses the River Rheidol.

One famous story from Padarn's Life is about King Arthur. King Arthur supposedly tried to steal Padarn's special tunic. When Padarn refused, Arthur stamped his foot, and Padarn made the earth swallow him up! Arthur had to beg for forgiveness to be released. This story might have borrowed from an older legend about a different Padarn. It's important because it links Saint Padarn to the legendary King Arthur.

The Life also says Padarn, along with Saint David and Saint Teilo, went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. There, the Patriarch of Jerusalem honored them. Padarn was given a tunic and a staff. Many of these stories about early saints are likely made up from different sources.

Padarn was said to lead his church for 21 years. During this time, he supposedly built many churches and started monasteries in the area of Ceredigion. He might have been buried on Bardsey Island, known as the "Island of 20,000 saints." But we cannot be sure about any of these details.

The Church as a Learning Center

The clas church remained important after 601. In 720, the area of Llanbadarn was attacked. This might have led to the church losing its bishop. However, this is not certain. Another tradition says the bishop was killed by locals, which caused the loss of the bishop's status.

Even if there was no bishop at Llanbadarn later on, the clas remained powerful. By the mid-800s, it was the wealthiest in the region. Asser, a famous scholar and advisor to King Alfred the Great, might have studied at Llanbadarn Fawr. This shows that Llanbadarn was known for its learning.

Sulien and His Family's Influence

By the 900s, records become clearer. The Welsh coast was often raided by Vikings. In 987, the clas was destroyed by the Danes. In 1038, the church was burned down by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. But the clas always survived.

During this time, the Llanbadarn community was led by Sulien (1011–1091) and his family. Sulien was born into a family that had been educated at Llanbadarn Fawr for many generations. He studied in Scotland and Ireland before returning around 1055. After this, Llanbadarn Fawr became perhaps the most important place of learning in Wales. Sulien became known as Sulien the Wise. He was the abbot of Llanbadarn Fawr and served as Bishop of St David's twice. Under his leadership, the church's monastic library grew very large. It was said to be bigger than the libraries of Canterbury Cathedral and York Minster.

Sulien's son, Rhygyfarch, wrote the Life of St David around 1081–1090. This book was meant to help restore the damaged church. Rhygyfarch and his brother Ieuan were talented poets. Ieuan also copied manuscripts and wrote a poem about Padarn's staff, Cyrwen.

The Ricemarch Psalter, a rare manuscript from the 1000s, was also created at Llanbadarn around 1079.

Norman Influence and Changes

In the late 1000s, the church in Wales began to be influenced by the Normans. But Llanbadarn Fawr still kept its Welsh traditions. However, bigger political changes were coming.

The Normans arrived in Ceredigion around 1073. Their influence grew, especially after 1115 when Norman bishops were appointed to St David's. Around 1106, Llanbadarn Fawr was one of the few places not destroyed by fighting.

A Short Time as a Priory

Between 1111 and 1117, the old clas church was given to St Peter's Abbey in Gloucester. This abbey was a Benedictine house. Llanbadarn became a small priory (a smaller monastery dependent on a larger one). This might have been when the first stone church was built here. A new tower and porch were added.

The Benedictine monks stayed for only about 20 years. In 1136, Welsh princes fought and won against the Normans. They drove the English monks away from Llanbadarn. It seems the Celtic monks then returned to their old clas.

The Church's Decline and Royal Control

The church was restored as a clas or a college of secular priests before 1144. But the golden age of the clas churches was over. Gloucester Abbey tried to get the church back several times but failed.

In 1188, Gerald of Wales, a writer and church leader, visited Llanbadarn Fawr. He described the church as being run by secular canons (priests who were not monks) under a lay abbot (a non-religious leader). Gerald was a reformer and didn't approve of everything he saw. He mentioned that the abbot was "an old man, grown old in wickedness." He also heard a story about a bishop of Llanbadarn being murdered.

Welsh rule was briefly interrupted in 1211. By 1246, the church came under the control of the English Crown. King Henry III took control of the church's advowson (the right to appoint the priest). This was possibly to help pay for building the new church. The building of the current church likely began around this time. Its large size suggests it was a royal project.

The church was now led by a rector, who replaced the lay abbot. Any remaining clas priests were probably removed. The church's status declined as the college gradually ended.

The church was said to have been rebuilt after a serious fire around 1257–1265. This fire might have happened when Llywelyn ap Gruffudd seized Llanbadarn Fawr from Norman control in 1256. The construction of such a large church would have taken many years.

The rectors were usually royal favorites or important church leaders who rarely visited the church. One notable rector was Antony Bek, who was also a bishop and a warrior.

Later Middle Ages and New Control

The college of priests likely ended before 1361. In 1346, King Edward III gave the right to appoint the rector to his son, the Black Prince. One of his appointments was Thomas Bradwardine, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. He was rector of Llanbadarn Fawr from 1347 to 1349.

The church continued to be a rich position for its rector, but the actual work was done by a resident vicar. Many rectors were important figures, but some were less respectable. One rector, Robert Stretton, was nominated as a bishop even though it was claimed he couldn't read or write.

Dafydd ap Gwilym, one of Wales's greatest poets, is traditionally said to have been born in the Llanbadarn Fawr parish in the 1300s. He wrote a famous poem called "The Girls of Llanbadarn" about the church.

In 1360, the church was given to Vale Royal Abbey, a Cistercian monastery in Chester. The abbot and monks of Vale Royal became the corporate rector until 1538. This meant they received the church's income, and Llanbadarn Fawr was left in the hands of a vicar. This transfer helped Vale Royal Abbey fund repairs to their own church.

Chancel Extension and Monastery Closures

Even though it was controlled by Vale Royal Abbey, Llanbadarn Fawr church remained important. The building was greatly extended in 1475, with a large new sanctuary (the area around the altar). It also had a Rood screen and loft, with a carved image of Christ. These are now gone.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII in 1538, Vale Royal Abbey was closed. St Padarn's Church became independent again, but only as a parish church. It no longer had a religious community living there. The church remained important because its parish was one of the largest in Wales, covering over 240 square miles. However, the church lost its income from tithes (payments) and lands.

Later Life as a Parish Church

Even after the monks and priests left, the church remained an important center for education and culture. William Morgan, who later became a bishop, was the first person to translate the entire Bible into Welsh in 1588. He was the vicar of Llanbadarn Fawr from 1572 to 1575.

Because the mediaeval parish of Llanbadarn was so huge, it was impossible for everyone to travel to the main church for Sunday worship. So, smaller churches and chapels were built in distant areas. These were called "chapels of ease." Churches like Llanbadarn, with many smaller churches around them, are often called mam-eglwysi (mother churches).

Over time, as the population grew, the original parish of Llanbadarn Fawr was divided into about 17 new parishes with 20 churches.

By the mid-1800s, the church building itself was in poor condition. It needed major repairs. While necessary, this work removed many of the old details inside the church. Today, most of what you see inside is from the 1800s, except for the church's main structure and some older monuments.

The Church Today

In 2014, the church had £100,000 worth of repairs. This included replacing the old heating system and replastering the inside walls.

The church is now part of a group of churches called the Benefice of Llanbadarn Fawr and Elerch and Penrhyncoch and Capel Bangor. It is in the Diocese of St David's.

The church has both Welsh and English language services. The current Vicar is the Reverend Andrew Loat, who was appointed in 2014.

The church is also part of "Peaceful Places", a heritage tourism trail that shares the stories of churches and chapels in North Ceredigion.

Organ

The church has a large pipe organ from 1885, made by Forster and Andrews. It has two keyboards and 14 stops (different sounds). You can find more details about it on the National Pipe Organ Register.

Architecture of St Padarn's Church

There are no parts left of the very first clas church. Most buildings in the 500s were made of wood and mud. Even churches were usually wooden. Stone was rarely used in Wales until the 1100s. Early churches were small, often less than 40 feet long, with a single main room and a small square area for the altar.

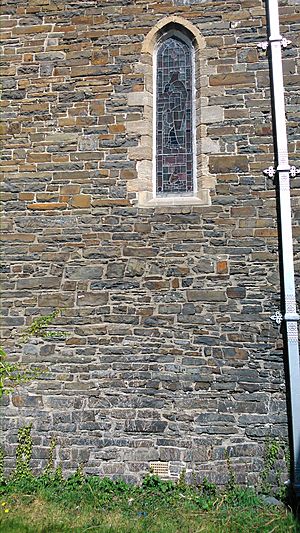

The current church building has many signs of being very old. It is large and shaped like a cross. The earliest stone parts you can see are from the 1200s, in the tower and the arches that support it. The outside of the church looks big and old, built with rough stone. The thick walls of the main part (nave) suggest Norman style, but the pointed windows show it's early Gothic, probably from the early 1200s. The church was rebuilt after a fire in the 1200s, and the chancel (area around the altar) was extended in the 1400s. After that, the church looked much as it does today.

The Outside of the Church

Outside, the church has slate roofs and pointed gables. The roofs have patterns made from different colored slates. The walls are large and plain. There is a porch on the south side, two side sections (transepts), and the chancel. A new vestry (room for priests) was added in the 1800s.

The tower has many small holes from its construction. It stands on four huge columns and has a short, eight-sided spire from the 1800s. The tower has a set of bells. The oldest bells were made in 1749. More bells were added in 1886 and 2000. The tower is one of the most noticeable sights in Aberystwyth. It also has a clock from 1859.

The church is about 163 feet long.

The Chancel

The inside of the church has a chancel, a nave (main seating area), transepts, and a south porch. The walls are mostly plastered and whitewashed.

The large chancel was restored around 1475. It was made longer, and new red sandstone windows were added. These windows now have stained glass from the 1800s.

There are old inscriptions on the window frames. One might be a memorial to William Stratford from the 1400s. Another is for Thomas ap Dafydd and his wife Angharad. The large five-light east window is also made of red stone with 1800s Gothic style patterns.

The chancel has a beautiful wooden ceiling with carved angels and patterns. This ceiling was put in during 1882–1884. It hides the original 1400s ceiling above it.

The entrance to the chancel has red marble steps and patterned tiles. The sanctuary (the area closest to the altar) has more marble steps and pink and black marble flooring.

There are three small doors on the north wall of the chancel. One leads to a hidden staircase that went up to the old rood loft (a platform above the screen). The third door leads to the priests' vestry.

The high altar from the 1880s has a beautiful carved screen (reredos) behind it, made of red sandstone and white marble. It has symbols like Alpha and Omega and phrases like "Praise be to God." Wooden altar rails protect the sanctuary.

The Crossing

The crossing is the central area where the nave and transepts meet. It has a complex oak roof with heavy beams and carved decorations. The massive arches that support the tower are from the early 1200s.

The pews in the crossing are made of pine and are more decorated than those in the nave.

The organ is located at the entrance to the south transept. It was a gift from Sir Pryse Pryse in 1885.

The South Transept (St Padarn's Chapel and Exhibition)

The transepts have wooden ceilings. Each transept has pointed spaces in the end wall that might have held tombs.

The south transept is now a museum and a chapel dedicated to St Padarn. It was built between 1985 and 1988. The exhibition shows the rich history of the area, with displays about St Padarn and people like William Morgan. There are also three niches (recesses) that might have held statues of priests.

A pine screen with etched glass panels leads to the new rooms in the transept. The screen has lines from the poetry of Dafydd ap Gwilym. There is also a ceramic coat of arms on the screen.

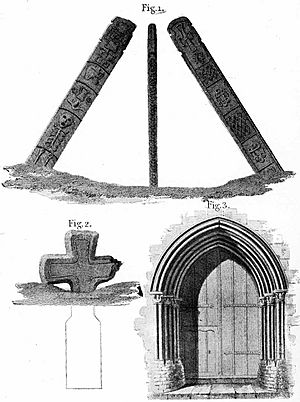

The church has two very old carved stone crosses, which have been in the south transept since 1987. One cross is short and squat, with a rough human figure. It might be from the late 900s.

The second cross is tall and slender, with carvings in a traditional Welsh style. One figure looks like a saint. This cross is made of granophyre stone and has Celtic patterns. It is thought to be from between the 800s and 1000s.

In the center of the transept, there is a low slate altar stone with a Chi-Ro emblem (an early Christian symbol). There is also a rough granite seat and kneeling desk. The floor has white and red tiles around the two old Celtic crosses. In the south wall, there are windows from the 1920s/1930s showing Saints Padarn, Dewi, and Teilo. The Padarn window shows St Padarn holding a staff and chalice.

The staff in the window is probably meant to be Cyrwen, Padarn's staff, which was a very important relic. The Life of Padarn says he received it from the Patriarch of Jerusalem.

There are also small exhibition rooms. One is Sulien's room, which has text from a poem about Sulien. Another room has historical exhibits in display cases.

The North Transept (The Lady Chapel)

The north transept is now called the Lady Chapel. It has two niches, similar to those in the south transept. One holds a picture of St Padarn. A statue of the Virgin and Child was given in memory of parents of a local priest.

The fittings in the north transept are from 1936 and are made of pale oak. They include a beautifully carved screen (reredos) with a Crucifixion scene. There is also a small Orthodox icon of the Virgin and Child.

The floor of the Lady Chapel is made of quarry tiles.

The nave, the main seating area, has no side aisles. The pews are made of pine. Most of the stonework in the nave's south wall is from the 1800s.

The nave roof becomes more detailed closer to the chancel.

The old font near the west door is from the 1100s. It has an arched basin and an eight-sided shaft. It is made of Purbeck Marble, which is unusual for Wales. The font was restored in the 1860s. The font cover is from the 1800s.

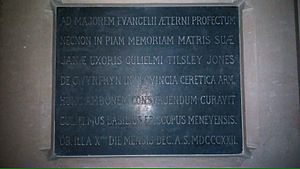

The pulpit (where sermons are given) is from 1879. It was given in memory of the mother of Bishop Basil Jones. It is made of stone and has carved figures of Saints John and Paul. Opposite the pulpit is a brass eagle lectern (for reading lessons).

The lights in the nave and transepts were designed by George Pace in the 1960s.

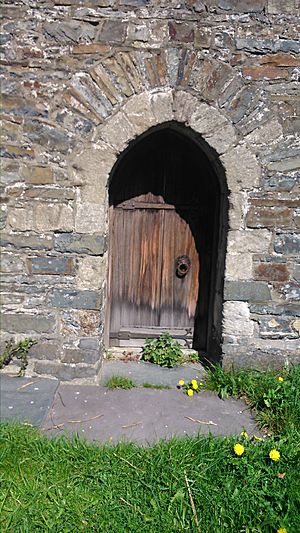

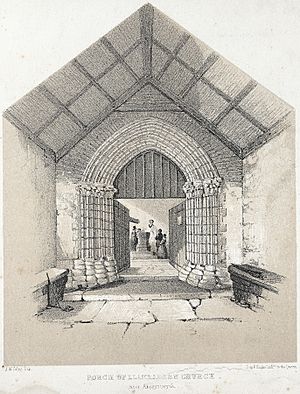

The Porch and Archway

The inner porch, made of oak with narrow leaded windows, was built by George Pace in the 1960s.

The west door, which is actually on the south side of the church, is a beautiful pointed arch. It is traditionally said to have come from Strata Florida Abbey, but this is uncertain. It is very ornate and is considered the finest work of its kind in the county.

The 1800s porch has a large stone arch, stone benches, and a tiled floor. It has three steps leading up to the oak double doors.

The Monuments

Many monuments from the 1600s and 1700s survive, mostly in the chancel. These include memorials to important landowning families like the Powells of Nanteos and the Pryses of Gogerddan. Some are very large.

The central aisle and cross aisles have a beautiful mosaic floor with patterned tiles.

The Windows

Almost every window in the church has colored glass. Most are narrow single windows. The west and south ends have three windows, two below and one above. The north side has two windows.

The east window is a memorial to Mrs. Rosa Edwyna Powell and her daughter Harriet. It shows the Transfiguration of Jesus Christ. It was designed in the 1880s. Other stained glass windows were added by parishioners in 1894 in memory of the Reverend John Pugh.

The last window that had plain glass was given stained glass in the late 1900s. It was commissioned by Professor Ian Parrott, a local musician, and designed by John Petts. The window's theme is "Music in Praise of the Lord."

1800s Restoration Work

In 1810, the church still had beautiful mediaeval screens, but these were lost during repairs between 1813 and 1816.

The church was in poor condition in the mid-1800s. The walls were leaning, and the roofs were decaying. Major restoration work was carried out from 1867 to 1884 by John Pollard Seddon. The church was largely rebuilt at a cost of £8,500. The roof was replaced, except for the 1400s chancel roof, which survives above Seddon's new roof.

The nave was in the worst condition and was largely rebuilt. Traces of painted decorations, including a huge St Christopher, were found on the nave walls. Sadly, these could not be saved and were destroyed.

The tower and transepts were restored between 1878 and 1880. The pulpit also dates from this time. The chancel was restored from 1880 to 1884.

Further repairs and additions were made in the 1930s and 1960s. The museum and St Padarn's chapel are the most recent additions, apart from the bells being re-cast.

Building Listing

The church has been a Grade I listed building since January 21, 1964. This means it is considered a very important mediaeval church in the region, with excellent monuments and beautiful 1800s fittings and stained glass.

Churchyard

The churchyard covers about two acres. Most of the headstones are from the 1800s, but there are some older monuments. The churchyard is now closed for new burials. The entire churchyard and church are surrounded by an oval shape of trees, which was typical for early Celtic churches. There might also be signs of an old pond, possibly used for keeping fish for the priests and monks who lived there long ago.

Lewis Pugh Evans

Brigadier-General Lewis Pugh Evans, a hero from World War I who received the Victoria Cross, is buried in the churchyard. His grave has a simple slate headstone. He was awarded the Victoria Cross for his incredible bravery and leadership in 1917 during a battle in Belgium. He led his battalion through heavy enemy fire, captured enemy positions, and continued to command even after being badly wounded twice. His courage inspired everyone around him.

He was also a local judge and a Freeman of Aberystwyth. A memorial plaque for him has been on the wall near the village war memorial since 1991.

Churchyard Gates

The churchyard gate to the south-west of the church is a Grade II listed building (since October 26, 2002).

The lychgate (a roofed gateway to a churchyard) to the south-east is also a Grade II listed building (since October 25, 2002). It is a stone gate with arches and iron gates, dating from 1814.

The Church Hall

There is a modern church hall just outside the church grounds, to the west. It was restored in 2000.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |