Xenarthrans facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Xenarthrans |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Placentalia |

| Superorder: | Xenarthra Cope, 1889 |

| Orders and suborders | |

|

|

Xenarthra is a special group of placental mammals that live in the Americas. The name comes from ancient Greek words meaning "foreign" or "strange" and "joint." This is because they have unique joints in their spines. Today, there are 31 different kinds of xenarthrans. These include anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos. Long ago, there were also huge extinct xenarthrans like glyptodonts and giant ground sloths.

Xenarthrans first appeared in South America about 60 million years ago. They developed many different forms while South America was separated from other continents. Later, they spread to the Antilles and then to Central and North America. This happened about 3 million years ago during an event called the Great American Interchange. Sadly, most of the very large xenarthrans died out at the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age.

Xenarthrans have several features that other placental mammals do not. These features suggest their ancestors might have been diggers that hunted insects underground. Their name, "Xenarthra," means "strange joints" because their backbones have extra connections. These extra joints are different from those in other mammals. Also, their hip bones are joined to their spine. Xenarthrans have strong limb bones with large areas for muscles to attach. Living xenarthrans are incredibly strong for their size. They also have unusual limb structures and can only see one color. Their teeth are very unique, too. Many scientists think xenarthrans are among the oldest types of placental mammals. They also have the lowest metabolic rates (how fast their bodies use energy) among mammals.

Here are some types of xenarthrans and how they live:

- Armadillos: These are usually small, but some are larger. They eat both plants and insects. They have flexible, banded armor covering their bodies.

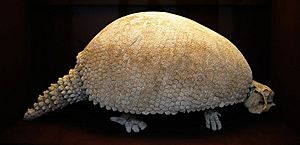

- Glyptodonts: These were large plant-eaters. They had a hard, dome-shaped shell.

- Pampatheres: These were also large plant-eaters, and possibly ate some meat. They had banded body armor like armadillos.

- Anteaters: These range from small to large. They are special eaters of social insects like ants and termites.

- Tree sloths: These are medium-sized animals that eat leaves. They are experts at hanging upside-down in trees.

- Ground sloths: These were medium to very large sloths that lived on the ground. They ate plants, and some might have eaten meat.

- Aquatic sloths: Thalassocnus is the only known sloth that lived in water. It was a medium-sized plant-eater.

Contents

How Xenarthrans Are Related

Xenarthrans were once grouped with pangolins and aardvarks in an order called Edentata. This name meant "toothless" because these animals often lacked front teeth or had simple back teeth. However, scientists later found that Edentata was not a true group. The animals in it were not closely related. So, aardvarks and pangolins were placed in their own groups. The new order Xenarthra was created for the remaining families, which are all related.

Scientists now generally agree that anteaters and sloths are more closely related to each other than they are to armadillos. This idea is supported by studies of their DNA. Xenarthra is now often seen as a very important group, sometimes called a "cohort" or "superorder."

This big group, Xenarthra, is divided into two main orders:

- Cingulata: This group includes armadillos and the extinct glyptodonts and pampatheres. Their name means "the ones with belts or armor."

- Pilosa: This group means "the ones with fur." It is divided into two sub-groups:

- Vermilingua: These are the anteaters, whose name means "worm-tongues."

- Folivora: These are the sloths, both tree sloths and the extinct ground sloths. Their name means "leaf-eaters."

How xenarthrans relate to other placental mammals is still a bit of a mystery. Some studies suggest they are related to a group called Afrotheria. Others say they are related to Boreoeutheria. Still others suggest they are a sister group to all other placental mammals. Studies using DNA have given different answers. However, a large study of both living and fossil mammals suggests that placental mammals first split into Xenarthra and all other placentals after the time of the dinosaurs.

Amazing Xenarthran Features

Xenarthrans have several features that are not found in other mammals. Many experts agree that they are a very old group of placental mammals. They are not closely related to other mammal groups. In 1931, scientist George Gaylord Simpson suggested that their unique features show they came from ancestors that were highly specialized. These early ancestors likely lived underground or were active at night. They probably used their front limbs to dig for social insects like ants or termites. Most researchers since then have agreed with this idea. These extreme features made it hard to tell them apart from unrelated animals with similar habits, like aardvarks and pangolins.

Unique Teeth

The teeth of xenarthrans are different from all other mammals. Most species have very few teeth, or their teeth are greatly changed, or they have no teeth at all. Except for Dasypus armadillos, xenarthrans do not have baby teeth. They have only one set of teeth throughout their lives. These teeth do not have strong enamel, which is the hard outer layer found on most mammal teeth. Also, they usually have few or no teeth at the front of their mouths. Their back teeth all look very similar. Because most mammals are identified by their teeth, it has been hard to figure out how xenarthrans relate to other mammals.

Xenarthrans might have come from ancestors that had already lost basic mammal tooth features. These include tooth enamel and teeth with pointed tops (cusps). Simple, reduced teeth are often found in mammals that eat social insects by licking them up. Some xenarthran groups did develop cheek teeth to chew plants. But since they lacked enamel, patterns of harder and softer dentine created grinding surfaces. Dentine wears down more easily than enamel-covered teeth. So, xenarthrans developed teeth that grow continuously from their roots. Today, no living or extinct xenarthrans have the standard mammal tooth arrangement or tooth shape.

Strong Spines

The name Xenarthra means "strange joints." This name was chosen because the backbones of these animals have extra joints. These are unlike those of any other mammals. This feature is called "xenarthry." (Tree sloths lost these extra joints to make their spines more flexible, but their fossil ancestors had them.) These extra points where vertebrae connect make the spine stronger and stiffer. This is a useful adaptation for animals that dig for food.

Xenarthrans also tend to have different numbers of vertebrae than other mammals. Sloths have fewer lower back vertebrae. They also have either more or fewer neck vertebrae than most mammals. Armadillos have neck vertebrae that are fused together. Glyptodonts even had their chest and lower back vertebrae fused.

Single-Color Vision

Scientists have found that xenarthrans can only see one color. Studies of their DNA show that a change in an early xenarthran led to them having only one type of light-sensing cell (cone) in their eyes. This type of single-color vision is common in animals that are active at night, live in water, or live underground. Further changes led to even more reduced eyesight in early armadillos and sloths/anteaters. This suggests their ancestors lived underground. Some experts also believe that xenarthrans do not have a working pineal gland. This gland is involved in how animals sense light.

Low Metabolism

Living xenarthrans have the lowest metabolic rates (how fast their bodies use energy) among mammals. Very large ancient burrows have been found, up to 1.5 meters wide and 40 meters long. These burrows have claw marks from giant ground sloths. Remains of ground sloths are common in caves, especially in colder areas. This suggests ground sloths might have used burrows and caves to help control their body temperature.

Studies of ancient animals in South America suggest that many more large plant-eating mammals lived there than similar places today could support. Most of these large plant-eaters were xenarthrans. Their low metabolic rate might have allowed even dry, scrubby lands to support many huge animals. Studies also show that before the Great American Interchange, South America had far fewer large predators than expected. This suggests that other things, not just predators, controlled the number of xenarthrans. South America had no placental predatory mammals until the Ice Age. So, xenarthran populations might have been vulnerable to new predators, competition from North American plant-eaters with faster metabolisms, and climate change.

See also

In Spanish: Xenartros para niños

In Spanish: Xenartros para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |