Great American Interchange facts for kids

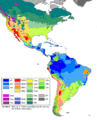

The Great American Interchange was a huge natural event that happened about three million years ago. It was when land animals and freshwater creatures moved between North America and South America.

This big migration took place during a time called the Pliocene epoch, roughly 3.6 to 2.6 million years ago. A chain of volcanoes pushed up from the ocean floor, forming the Isthmus of Panama. This created a natural land bridge connecting the two continents.

This new land bridge in what is now Panama linked the Neotropic region (which is mostly South America) with the Nearctic region (mostly North America). Together, they formed the Americas.

We can see the effects of this interchange in the rocks and in nature today. It had the biggest impact on where different mammals live. But other creatures also moved, like birds that don't fly well, reptiles, amphibians, arthropods (like insects), and even freshwater fish.

Scientists like Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin knew that the animals in North and South America were very different. The idea of this "interchange" was first fully explained in 1876 by Alfred Russel Wallace. He is sometimes called the "father of biogeography" (the study of where living things are found). Wallace had explored the Amazon Basin and collected many specimens. Other important scientists who helped us understand this event were Florentino Ameghino and George Gaylord Simpson.

Similar animal movements happened earlier in Earth's history. For example, when the old supercontinent Gondwana broke apart, India and Africa later connected with Eurasia. This happened about 50 and 30 million years ago.

Contents

How Continents Moved: Plate Tectonics

Long, long ago, there was one giant continent called Pangaea. It started to break apart during the Jurassic period. This led to the formation of a huge southern supercontinent called Gondwana. Gondwana separated from Laurasia about 200 to 180 million years ago.

Over time, Gondwana also broke into smaller pieces. These pieces eventually became the continents we know today: Australasia (Australia), India, Africa, Madagascar, Antarctica, and South America.

South America slowly drifted west from Africa. This started about 130 million years ago. By 110 million years ago, there was a wide ocean between them. The very last connection South America had with any part of Gondwana was with West Antarctica. This link finally broke about 30 million years ago, during the Oligocene epoch.

Why Continent Movement Matters for Animals

When Gondwana separated from Laurasia, most animals and plants on each supercontinent evolved on their own. Later, as Gondwana itself broke apart, the living things on each new landmass continued to evolve separately.

This also happened when Africa and India moved north and joined the Eurasian continent a very long time ago. However, that was so many millions of years ago that it's hard to see the original patterns today. But in Australasia and South America, the patterns of evolution are still very clear.

Mammals are a great example. Most modern mammals, called Eutherians, evolved in Laurasia. But only a few reached Gondwana before it split up. Older groups of mammals did get to Gondwana. These included marsupials (like kangaroos), monotremes (like platypuses), and other early mammals that are now extinct.

So, when South America became a completely separate island continent, it only had these older types of mammals. This included some early eutherians like the xenarthrans. The mammal groups that evolved later, and which are common in the northern continents, only arrived in South America because of the Great American Interchange.

South America's Unique Animals

After the supercontinent Gondwana broke up, South America spent most of the Cainozoic era as an island continent. This "splendid isolation" allowed its animals to evolve into many unique forms. Most of these are now extinct.

Early Mammals in South America

The unique mammals that first lived in South America included metatherians (like opossums and shrew opossums), xenarthrans (like armadillos and sloths), and a wide variety of South American ungulates (hoofed animals).

It seems that marsupials traveled from South America, through Antarctica, and then to Australasia (Australia and New Zealand). This happened in the late Cretaceous or early Tertiary period.

Large, flightless birds called Ratites (like ostriches, related to South American tinamous) probably also used this route. They likely moved from South America towards Australia and New Zealand around the same time.

Other animals that might have spread this way (if they didn't fly or float on rafts of vegetation) include parrots, certain turtles, and extinct giant turtles.

One living South American marsupial, the tiny Monito del Monte, is actually more closely related to Australian marsupials than to other South American ones. Since it's a very old type of marsupial, its group likely evolved in South America. Then, some of them moved to Australia.

A 61-million-year-old fossil of a monotreme (like a platypus) found in Patagonia might be an ancient immigrant from Australia.

Ancient Predators

The borhyaenids and the sabertooth Thylacosmilus were once thought to be marsupials. They are actually sparassodont metatherians, which are a related group to marsupials. Sparassodonts were the only South American mammals that became specialized meat-eaters. They weren't super efficient predators. This left opportunities for non-mammal predators to be more common, similar to what happened in Australia.

Sparassodonts shared their hunting roles with scary, flightless "terror birds" (phorusrhacids). Their closest living relatives are the seriemas. Land-dwelling crocodilians were also present at least until the middle Miocene epoch. Some of South America's water-dwelling crocodilians grew to enormous sizes, up to 12 meters long!

About 6 million years ago, the largest flying bird known, the teratorn Argentavis, soared through the skies over South America. It had a wingspan of 6 meters or more. It might have eaten the leftovers from Thylacosmilus kills.

Later Herbivores

Xenarthrans are a very interesting group of mammals. They developed special body features for their diets very early in their history.

Besides the ones alive today (like armadillos, anteaters, and tree sloths), there were many other large types. These included pampatheres, the ankylosaur-like glyptodonts, and various ground sloths. Some ground sloths were as big as elephants, like Megatherium. There were even sloths that lived partly in water!

The notoungulates and litopterns were other strange groups of hoofed animals. They showed many examples of convergent evolution, meaning they developed similar features to animals in other parts of the world.

Both these groups started evolving in the early Paleocene epoch. They became very diverse but started to decline before the Great American Interchange. They finally became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Other strange groups like the pyrotheres and astrapotheres were less diverse and disappeared even earlier, long before the interchange.

The animals in North America were typical northern eutherian mammals. They also had some Afrotherian animals like proboscids (elephants and their relatives).

Animal Invasions

Once the continents were connected, many animals moved from North America to South America. This had a big impact. However, far fewer animals moved from South America to North America, and their impact was much smaller. This is clearest when we look at mammals.

Why Did More Animals Move South?

Scientists have suggested reasons for this. Animals from the wet, tropical areas of South America moving north would have faced desert or very dry conditions in Mexico. The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, also known as the Sierra Nevada, stretches 900 km across central-southern Mexico. This dry area might have been a barrier.

However, the most common idea is that North American animals were "topped up" with new species from Eurasia. These Eurasian species could cross the Bering Strait from time to time.

Mammals: A Special Case

This idea is especially true for mammals. Eutherian mammals first appeared in Asia and had evolved a lot before they reached South America. Marsupials that once lived in Eurasia had been out-competed and died out long ago. So, it's not surprising that the eutherians did very well when they arrived in South America.

Marsupials in both South America and Australasia were not very strong when it came to predators. The borhyaenids and Thylacosmilus (the 'marsupial' sabretooth) were not true marsupials; they were the related group called sparassodonts. For a long time in South America, the terror birds (like Phorusrhacos) were the top predators.

All these native South American predators were eventually wiped out. New predators like short-faced bears, wolves, nine species of small cats, cougars, jaguars, lions, and sabretooths (Smilodon and Homotherium) established themselves.

The animals that successfully moved from South America to North America are interesting. Opossums, like the Virginia opossum, are now common across a wide area. They are the only marsupial still living in North America today, though others lived there before humans arrived.

For a long time, the most successful native South American mammals to move north were the xenarthrans. Two different groups of large xenarthrans made it to North America. One group was the giant ground sloths, like Megalonyx. This group lived in North America for over 10 million years, long before the Great Interchange. How they got there is still a mystery. They even reached as far north as Alaska and the Yukon.

The other group was the glyptodonts, such as Glyptotherium texanum. These were large, heavily armored relatives of the armadillo.

The ability of South America's xenarthrans to compete well against the northern animals is a special case. One reason for their success was their defense against predation. This was based on body armor and/or powerful claws. Xenarthrans didn't need to be fast or super smart to survive. This strategy might have been necessary because of their low metabolic rate (the lowest among mammals). Their low metabolism also meant they could survive on less food or food that wasn't as nutritious. Sadly, the defenses of the large xenarthrans were useless against humans armed with spears and other projectiles.

Images for kids

-

The giant anteater, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, the largest living descendant of South America's early Cenozoic mammalian fauna

-

Capybara, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris

-

Emperor tamarin, Saguinus imperator

-

Red-footed tortoise, Chelonoidis carbonaria

-

†Titanis walleri, the only known North American terror bird

-

The Virginia opossum, Didelphis virginiana, the only marsupial in temperate North America

-

The North American porcupine, Erethizon dorsatum, the largest surviving Neotropic migrant to temperate North America

-

Baird's tapir, Tapirus bairdii, the largest surviving Nearctic migrant to South America

-

Gray tree frog, Hyla versicolor

-

Nine-banded armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus

-

The glyptodont †Glyptotherium

-

The megatheriid ground sloth †Eremotherium

-

Strawberry poison-dart frog, Oophaga pumilio

-

Spectacled caiman, Caiman crocodilus

-

The two-toed sloth Choloepus hoffmanni

-

Central American agouti, Dasyprocta punctata

-

White-headed capuchin, Cebus capucinus

-

Great tinamou, Tinamus major

-

The camelid Lama guanicoe

-

†Cuvieronius, a gomphothere

-

The coati Nasua nasua

See also

In Spanish: Gran intercambio americano para niños

In Spanish: Gran intercambio americano para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |