Thalassocnus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thalassocnus |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| T. natans skeleton in its hypothesized swimming pose, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Nothrotheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Thalassocninae |

| Genus: | †Thalassocnus de Muizon & McDonald, 1995 |

| Type species | |

| †Thalassocnus natans de Muizon & McDonald, 1995

|

|

| Other species | |

|

|

Thalassocnus (say "Tha-lass-ock-nus") was an amazing extinct ground sloth. It lived a long time ago, during the Miocene and Pliocene periods. This sloth was special because it was semi-aquatic, meaning it lived partly in water and partly on land. Its fossils have been found along the Pacific coast of South America.

Scientists believe the five different species of Thalassocnus actually represent a single group that slowly changed over millions of years. They gradually adapted to life in the ocean. Thalassocnus is the only known sloth that lived in the water.

Over about 4 million years, Thalassocnus developed many cool features for marine life. Its bones became very dense and heavy, helping it sink in water. Its nose moved further back on its head, making it easier to breathe while submerged. The snout became wider and longer to help it eat water plants. Its long tail was likely used for diving and balance, much like a modern beaver's tail.

Thalassocnus probably walked along the seafloor and used its claws to dig for food. It wasn't a fast swimmer, but could paddle if needed. Early Thalassocnus likely ate seaweed and seagrass close to shore. Later species became specialists, eating seagrass in deeper waters. Large sharks and macroraptorial sperm whales, like Acrophyseter, might have hunted them.

Contents

Discovering Thalassocnus

How Scientists Found Them

Thalassocnus ground sloths lived from about 7 to 1.5 million years ago. All five species were found in different layers of rock in the Pisco Formation in Peru. Each layer represents a different time period. For example, T. antiquus lived about 7 or 8 million years ago. T. natans lived around 6 million years ago. The latest species, T. yaucensis, lived about 3 to 1.5 million years ago.

Fossils of Thalassocnus have also been found in Chile. These include T. carolomartini, T. natans, and T. antiquus.

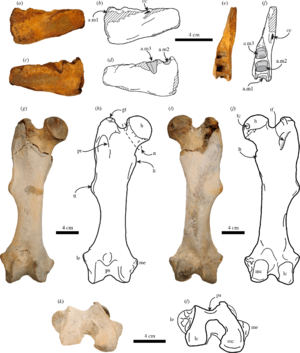

In 1995, paleontologists Christian de Muizon and H. Gregory McDonald officially described the genus Thalassocnus. They named the first species T. natans from a partial skeleton. Other species were described later, based on skulls, jaws, and other bones.

What Their Names Mean

The species name carolomartini honors Carlos Martin. He was the owner of the Sacaco hacienda and found many bones in the Pisco Formation. The name yaucensis comes from the village of Yauca, which is near where that species was discovered.

Thalassocnus Family Tree

Scientists have debated where Thalassocnus fits in the sloth family tree. At first, it was placed in the Megatheriidae family. Then, it was moved to the Nothrotheriidae family. Later, it was moved back to Megatheriidae. These two families are very closely related, so it's tricky to be sure.

The five species of Thalassocnus seem to form a direct line of ancestors and descendants. This means one species slowly changed into the next over time.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of Thalassocninae assuming placement in the family Megatheriidae |

What Thalassocnus Looked Like

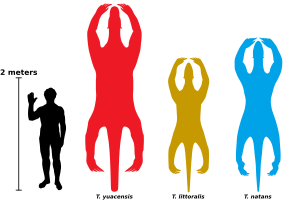

Thalassocnus is the only known aquatic xenarthran. Xenarthrans are a group of mammals that includes sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. As time went on, Thalassocnus species grew larger. The most complete skeleton, T. natans, was about 2.55 meters (8.4 feet) long from nose to tail. The largest species, T. yuacensis, could be around 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) long.

Heavy Bones for Diving

Later species of Thalassocnus had very thick and dense bones. This condition is called pachyosteosclerosis. These heavy bones helped the animal sink to the seafloor, much like modern manatees. Early Thalassocnus had bone density similar to sloths that lived only on land. But over just 4 million years, their bones became incredibly compact. This shows how quickly they adapted to water.

Differences Between Males and Females

Thalassocnus might have shown sexual dimorphism. This means males and females of the same species looked a bit different. For example, some skulls of T. littoralis and T. carolomartini show differences in size and snout length. This is similar to how male elephant seals have larger noses than females.

Their Unique Skull

Later Thalassocnus species had longer snouts. Their lower jaws became more spoon-shaped. This might have helped them scoop up aquatic plants. They likely had strong lips, similar to modern plant-eating animals. Their nostrils moved from the front of the snout to the top, like in seals.

To help them feed underwater, the internal parts of their nose and throat were more developed. This allowed them to breathe even when their head was mostly submerged. Their bite also became stronger to grasp seagrass better. The latest species, T. carolomartini and T. yaucensis, might even have had a short trunk, like a tapir or an elephant seal.

Thalassocnus had special teeth with high crowns. They lacked canine teeth. Their teeth were prism-shaped and interlocked tightly for chewing. In earlier species, the teeth were more rectangular and used for cutting food. Later species had squarer, larger teeth designed for grinding food.

Backbone and Tail

Thalassocnus had a strong, stiff backbone. They had 7 neck bones, 17 back bones, and 3 lower back bones. What's really interesting is their tail: it had 24 tail bones, which is more than other ground sloths. This made their tail proportionally longer.

Their small neck bones suggest they had weak neck muscles. This is common in aquatic animals that don't need to hold their heads up high. However, the joint connecting their head to their neck was strong. This helped them keep their head in a fixed position while feeding on the bottom. Like whales, their head could line up directly with their spine.

The tail bones suggest strong muscles, similar to a beaver or platypus. These animals use their tails for balance and diving, not for swimming fast. The long tail of Thalassocnus probably helped them dive by providing downward force, resisting buoyancy.

Limbs and Claws

Later Thalassocnus species had strong arm muscles and relatively shorter arms. These features were likely adaptations for digging. They had five claws on each foot.

Their legs became less important for support, as they relied more on the water's buoyancy. They probably preferred to sit semi-submerged while resting. Their legs also became more flexible. Unlike other ground sloths that often stood on two legs, Thalassocnus's leg bones were slender.

Early species walked on the sides of their feet, like other sloths. But later species planted their feet flat on the ground. This helped them paddle and walk along the seafloor. One of their claws was always bent, possibly acting like a hook to anchor them while digging.

How Thalassocnus Lived

Thalassocnus were plant-eaters that lived near the coast. They likely became aquatic because the land became a desert, and there wasn't enough food on shore. Early species were general eaters, finding seagrass and seaweed along the sandy coast. They probably fed in shallow water, less than 1 meter (3.3 feet) deep. T. antiquus might have even eaten plants that washed ashore.

Later species, like T. carolomartini and T. yaucensis, likely fed in deeper waters. They were specialists, eating only seagrass from the seafloor. This is similar to how manatees and dugongs eat today. They probably ate Zostera tasmanica seagrass, which was found in the Pisco Formation.

Later Thalassocnus mostly walked across the seafloor instead of swimming through the water. They didn't have adaptations for fast swimming. They probably dug up seagrasses by their roots with their claws. They also used their strong lips to pull out grasses. Their diet might have included buried food too.

Thalassocnus may have used their claws to loosen dirt, cut plants, grab food, or anchor themselves to the seafloor. They might have even used their claws to hold onto rocks during strong waves. Some fossil bones show breaks that healed, suggesting an individual might have been thrown against rocks during a storm. This sloth might have used its claws to drag itself back onto shore.

Thalassocnus might have competed with dugongs for seagrass, though dugongs were rare in the area. They could have been killed by harmful algae blooms. Large predators like the sperm whale Acrophyseter probably hunted them. Injured sloths would have been easy targets for sharks.

Where Thalassocnus Lived

Fossils of Thalassocnus have been found in Peru and Chile. This area has been a desert since the Middle Miocene period.

The Pisco Formation in Peru is famous for its many marine animal fossils. Scientists have found several types of whales there, including baleen whales and beaked whales. Other animals found include seals, sea turtles, crocodiles, and many seabirds. There are also lots of shark fossils, including requiem sharks, hammerhead sharks, and the giant megalodon. Tuna and other fish fossils are also common. Livyatan (a giant sperm whale) and megalodon were likely the top predators in this ancient ocean.

In Chile, the Bahía Inglesa Formation also has many shark fossils. These include the great white shark and blue shark. Other marine mammals like seals and sperm whales have been found there too.

The Coquimbo Formation and Horcón Formation in Chile also have diverse shark populations. These include megalodon, great white sharks, and many other types of sharks. Several ancient penguin species have been found in all three of these formations.

Why Thalassocnus Disappeared

Thalassocnus became extinct at the end of the Pliocene period. This was due to a cooling trend in the ocean. The closing of the Central American Seaway changed ocean currents and made the water colder. This cooling killed off much of the seagrass along the Pacific South American coast.

Since later Thalassocnus species were specialists in eating seagrass, they lost their main food source. Their heavy bones and thin layer of fat, which helped them sink, would have made it hard for them to stay warm in colder water. Sloths also have a slow metabolism, meaning their bodies don't produce much heat. So, even if there was enough seagrass, Thalassocnus would have struggled to survive in the changing conditions.

See also

In Spanish: Thalassocnus para niños

In Spanish: Thalassocnus para niños

- Eionaletherium

- Pezosiren

- Metamynodon

- Desmostylia

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |