Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository facts for kids

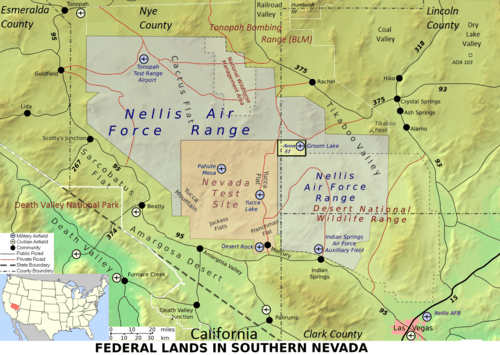

The Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository was a planned underground storage place for used nuclear fuel and other highly radioactive waste in the United States. It was meant to be built inside Yucca Mountain in Nye County, Nevada. This location is federal land, close to the Nevada Test Site, about 80 miles (129 km) northwest of Las Vegas.

The U.S. Congress approved the project in 2002. However, funding for the site was stopped in 2011 during the Obama Administration. The project faced many challenges and was strongly opposed by the public, the Western Shoshone people, and many politicians. The Government Accountability Office said the project stopped for political reasons, not because of safety or technical problems.

Because of this, the U.S. government and American nuclear power plants do not have a long-term storage solution for their high-level radioactive waste. This waste is currently kept in steel and concrete containers called dry casks at 76 reactor sites across 34 states.

Under President Barack Obama, the Department of Energy (DOE) looked into other options besides Yucca Mountain. A special group, the Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future, suggested in 2012 that a new, independent organization should find a suitable site. This new group would have direct access to the Nuclear Waste Fund, so it wouldn't be controlled by politics as much as the DOE. However, the Yucca Mountain site faced strong opposition in Nevada, especially from then-Senate leader Harry Reid.

Later, under President Donald Trump, the DOE stopped looking into other waste storage ideas. For a while, there were requests for money to continue work on Yucca Mountain, but Congress decided not to provide any funding. In 2020, it was confirmed that President Trump was strongly against the Yucca Mountain project. In 2021, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said that Yucca Mountain would not be part of the Biden administration's plans for nuclear waste disposal.

Contents

What is Yucca Mountain?

Used nuclear fuel is a radioactive leftover from making electricity at nuclear power plants. High-level radioactive waste also comes from processing used fuel to create materials for nuclear weapons. In 1982, Congress passed a law called the Nuclear Waste Policy Act. This law made the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) responsible for finding, building, and running an underground storage facility.

Scientists had suggested storing waste deep underground since 1957. They believed this was the best way to keep the environment and people safe. The DOE started studying Yucca Mountain in 1978. They wanted to see if it was a good place for the nation's first long-term underground storage site.

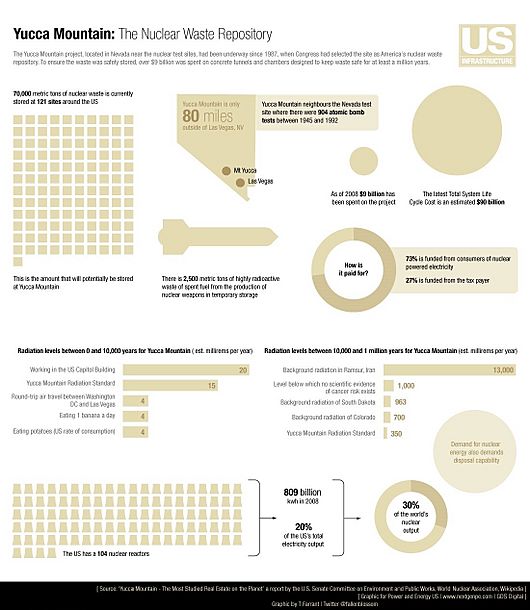

The plan was to store over 70,000 metric tons (150 million pounds) of used nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste. This waste was stored at 121 sites across the country. About 10,000 metric tons of this waste would come from America's military nuclear programs.

In 1984, the DOE chose ten possible locations in six states. After more studies, President Ronald Reagan approved three sites for detailed scientific study: Hanford, Washington; Deaf Smith County, Texas; and Yucca Mountain.

In 1987, Congress changed the law to focus only on Yucca Mountain. The law said that if Yucca Mountain was found unsuitable, studies would stop. However, this option ended when President Reagan officially recommended the site.

On July 23, 2002, President George W. Bush signed a resolution allowing the DOE to move forward with building the repository. The DOE was supposed to start accepting used fuel by January 31, 1998. But there were many delays due to legal challenges, worries about transporting the waste, and political pressure that led to not enough funding.

In 2006, the DOE suggested March 31, 2017, as the new opening date, assuming they got full funding. However, after the 2006 elections, Harry Reid, a strong opponent of the project, became the Senate Majority Leader. He said he would continue to block the project, famously stating, "Yucca Mountain is dead. It'll never happen."

The project's budget was cut in 2008. During his 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama promised to stop the project. After he was elected, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission told him he couldn't simply cancel it. Later, a court ruled in 2013 that nuclear power companies could stop paying into a special fund for nuclear waste storage. This was because the DOE wasn't following the law that named Yucca Mountain as the storage site. The fee ended in May 2014.

Without an operating storage site, the government had to pay utility companies hundreds of millions of dollars each year. This was compensation for not taking the used nuclear fuel by 1998, as promised in their contracts.

Inside the Facility

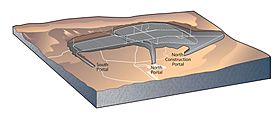

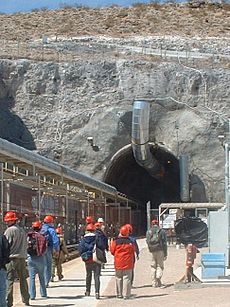

The Yucca Mountain project aimed to follow the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982. Its goal was to create a national site for storing used nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste. The main tunnel of the Exploratory Studies Facility is U-shaped, 5 miles (8 km) long and 25 feet (7.6 m) wide.

There are also several large, cave-like areas branching off the main tunnel. Most of the scientific experiments were done in these areas. The smaller tunnels where waste would have been stored were never built. This is because they needed special permission from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The repository had a legal limit of 77,000 metric tons (84,878 short tons) of waste. Storing that much waste would have needed 40 miles (64 km) of tunnels. The law also limited the amount of commercial used fuel to 63,000 metric tons. U.S. nuclear reactors would produce this much used fuel by 2014, if the fuel wasn't reprocessed. The U.S. currently has no reprocessing plants for civilian nuclear fuel.

By 2008, Yucca Mountain was one of the most studied geological sites in the world. The United States had spent $9 billion on the project, studying its geology and materials. The cost of the facility was paid for by a tax on nuclear power and by taxpayers for military nuclear waste.

The total cost of the project was estimated at $90 billion in 2008. This estimate was much higher than previous ones because it included a larger storage capacity and a longer operating period. The cost kept going up because there wasn't enough funding to finish the project efficiently. By 2007, the DOE wanted to double the size of the repository to 135,000 metric tons (148,812 short tons).

The tunnel boring machine (TBM) that dug the main tunnel cost $13 million. It was 400 feet (122 m) long when it was working. It now sits at the tunnel's exit point. The shorter side tunnels were dug using explosives.

Why People Opposed It

The DOE was supposed to start accepting used fuel at Yucca Mountain by January 31, 1998. But years after this deadline, the project's future was still uncertain. This was due to ongoing lawsuits and strong opposition from politicians like Harry Reid.

Because of construction delays, many nuclear power plants in the U.S. started storing waste on their own sites. They used large steel and concrete containers called dry casks.

The project is widely opposed in Nevada and is a big national debate. Many Nevadans feel it's unfair for their state to store nuclear waste when Nevada doesn't have any nuclear power plants. Their opposition also came from a 1987 law that stopped studies at other potential sites before conclusions were made. However, Nye County, where the facility would be, and six nearby counties supported the project. A 2015 survey found that 55% of Nevadans were open to discussing possible benefits.

One major concern was the safety standard for radiation over 10,000 to 1,000,000 years. In 2005, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggested a limit of 350 millirem per year for that period. The DOE later reported that the expected radiation dose would be much lower than this limit. For comparison, a hip X-ray gives a dose of about 83 millirem, and the average background radiation in the U.S. is about 350 millirem per year.

In 2002, Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham decided the site was suitable. Nevada's governor objected, but Congress overruled the objection. If the objection had stood, the project would have been stopped.

In 2005, some government hydrologists were accused of possibly faking quality control documents about water seeping into the mountain. However, a DOE report in 2006 confirmed that the water infiltration modeling was technically sound. A U.S. Senate committee report in 2006 concluded that Yucca Mountain was a good site, that not moving forward was costly, and that nuclear waste disposal was important for the environment and national security.

The DOE also brought in Sandia National Laboratories and Oak Ridge Associated Universities to review the scientific work. This was to ensure the project was based on sound science and to build trust.

Despite these efforts, there was significant public and political opposition in Nevada. For large projects that take decades, strong local opposition can often win, and this happened with Yucca Mountain. Successful nuclear waste storage projects in other countries have involved local communities in the decision-making process and given them a say. This did not happen with Yucca Mountain.

In 2009, Energy Secretary Steven Chu said that Yucca Mountain was no longer an option for storing reactor waste. In 2010, the DOE tried to withdraw its license application, but several lawsuits were filed to stop this.

A costly nuclear accident in 2014 at New Mexico's Waste Isolation Pilot Plant caused doubts about using that site as an alternative to Yucca Mountain. In 2019, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak vowed that "not one ounce" of nuclear waste would be allowed at Yucca Mountain. The Western Shoshone people view Yucca Mountain as sacred. A tribal elder said that a nuclear storage facility "will poison everything. It's people's life, our Mother Earth's life, all the living things here, all the creatures; whatever's crawling around, it's their life too."

Radiation Safety Standards

Original Rules

The EPA set its Yucca Mountain safety rules in June 2001. The storage rule set a limit of 15 millirem per year for people outside the site. The disposal rules had three parts: a limit for individuals, a rule for if humans accidentally intruded into the repository, and a groundwater protection rule. These rules set a limit of 15 millirem per year for the most exposed people.

The groundwater protection rule was similar to EPA's Safe Drinking Water Act standards. These disposal rules were meant to apply for 10,000 years after the facility closed.

Changing Rules

Soon after the EPA set these rules in 2001, the nuclear industry, environmental groups, and the State of Nevada challenged them in court. In 2004, a court ruled that the 10,000-year time frame was too short. The court said it didn't follow recommendations from the National Academy of Sciences.

The Academy had suggested that standards should be set for the time of highest risk, which could be up to one million years. By limiting the time to 10,000 years, the EPA didn't meet a legal requirement to follow the Academy's advice.

EPA's New Rule

In 2009, the EPA published a new rule. This new rule limits radiation doses from Yucca Mountain for up to 1,000,000 years after it closes. For the first 10,000 years, the limit remains 15 millirem per year. This is a very strict radiation limit. From 10,000 to one million years, the EPA set a dose limit of 100 millirem per year.

The EPA's rule requires the DOE to show that Yucca Mountain can safely contain waste. This includes considering the effects of earthquakes, volcanic activity, climate change, and container corrosion over one million years. Current studies suggest the repository would cause less than 1 millirem per year public dose for 1,000,000 years.

Geology of the Mountain

Yucca Mountain was formed by large eruptions from a caldera volcano. It is made of layers of volcanic rock called tuff. The tuff around the burial sites is expected to protect people by acting as a natural barrier to radiation. The mountain is located where the Mojave and Great Basin Deserts meet.

The volcanic tuff at Yucca Mountain has many cracks. Water moves through an underground water source (aquifer) below the waste repository mainly through these cracks. While most cracks stay within single layers of rock, some faults extend from the planned storage area all the way to the water table, which is 600 to 1,500 feet (183 to 457 m) below the surface.

Some opponents of the site worry that after the waste containers eventually fail, these cracks could allow radioactive waste to dissolve in water and move downward from the desert surface. Officials say that the waste containers would be stored in a way that would greatly reduce this possibility.

The area around Yucca Mountain received much more rain in the past. The water table was much higher then, but still well below the planned storage level.

Earthquakes

The DOE has stated that earthquakes and ground movements would not significantly affect the safety of the Yucca Mountain repository. Yucca Mountain is in an area where the ground is still moving, but these movements are too slow to greatly affect the mountain during the 10,000-year safety period. Any rises in the water table caused by earthquakes would be small and would not reach the repository.

The cracked and faulted volcanic rock of Yucca Mountain shows that many earthquakes have happened there over millions of years. However, the way water moves through the rock would not change much from earthquakes in the next 10,000 years. The engineered barriers would protect the waste from water, even during strong earthquakes.

In 2007, it was found that the Bow Ridge fault line ran under the facility, hundreds of feet from where it was first thought to be. This meant some structures had to be moved. Critics said that officials should have known about the fault line's location years earlier. In 2008, a nuclear equipment supplier criticized the DOE's safety plan. They worried that in an earthquake, unanchored containers of radioactive waste could be thrown around.

Moving the Waste

The plan was to ship the nuclear waste to the site by train or truck. It would be carried in strong containers called spent nuclear fuel shipping casks, approved by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. While the routes in Nevada would be public, the routes, dates, and times of transport in other states would be kept secret for security reasons. State and tribal leaders would be told before shipments entered their areas.

Nevada Routes

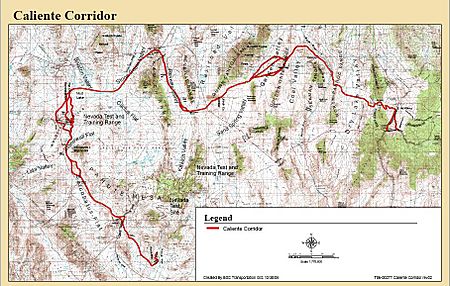

Within Nevada, the main way to transport the waste was by rail through the Caliente Corridor. This route would start in Caliente, travel along the northern and western edges of the Nevada Test Site for about 200 miles (322 km), and then turn south.

Another option was a rail route along the Mina corridor. This route would start near Wabuska and go southeast through Hawthorne, Blair Junction, Lida Junction, and Oasis Valley. Then it would turn north-northeast towards Yucca Mountain. Using this route would need permission from the Walker River Paiute Tribe to cross their land. It would also need permission from the Department of Defense.

Environmental groups and Nevada's Attorney General worried about the transportation routes. They were concerned about the waste passing through sensitive natural areas.

Effects of Transport

Since the early 1960s, the U.S. has safely moved over 3,000 shipments of used nuclear fuel. There have been no harmful releases of radioactive material. This safety record is similar to worldwide experience, where over 70,000 metric tons of used nuclear fuel have been transported since 1970. This amount is roughly equal to all the used nuclear fuel that would have been shipped to Yucca Mountain.

However, cities were still worried about radioactive waste being transported on highways and railroads through populated areas. An adviser to the state of Nevada said that cities like Buffalo, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Omaha, Atlanta, Nashville, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Las Vegas would be heavily affected. Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham said, "I think there's a general understanding that we move hazardous materials in this country, an understanding that the federal government knows how to do it safely." In 2018, a Utah state senator argued that transferring nuclear waste on state highways and railways could be a health hazard.

Cultural Importance

Archaeological studies have found signs that Native Americans used the Yucca Mountain area temporarily or seasonally. Some Native Americans disagree with these findings. They believe their ancestors farmed the area before Europeans arrived, not just hunted and gathered.

Yucca Mountain and the surrounding lands were very important to the Southern Paiute, Western Shoshone, and Owens Valley Paiute and Shoshone peoples. They used these lands for religious ceremonies, gathering resources, and social events.

Delays Since 2009

Starting in 2009, the Obama administration tried to close the Yucca Mountain repository. This was despite a U.S. law that named Yucca Mountain as the nation's nuclear waste site. The DOE began to carry out the President's plan in May 2009. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission also supported the administration's plan to close the site.

However, various states and members of Congress tried to challenge these closure plans in court and through laws. In August 2013, a U.S. Court of Appeals decision told the NRC and the Obama administration that they must either "approve or reject" the DOE's application for the waste storage site. The court said they could not simply plan for its closure against U.S. law. The court stated that "The president may not decline to follow a statutory mandate or prohibition simply because of policy objections."

In response, the NRC released reports saying that the site would meet all safety standards. However, they also said that construction shouldn't start until land and water rights were settled and an environmental impact statement was finished. In March 2015, the NRC ordered staff to complete this statement and make the Yucca Mountain licensing documents public.

In 2008, a U.S. Senate committee found that not following the contracts could cost taxpayers up to $11 billion by 2020. By 2013, this estimate rose to $21 billion. In 2009 and 2013, the House of Representatives voted against cutting funding for Yucca Mountain.

In April 2010, the state of Washington sued to prevent Yucca Mountain from closing. They argued it would slow down cleanup efforts at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. South Carolina and others joined the lawsuit. The court dismissed the suit in 2011, saying the Nuclear Regulatory Commission had not yet ruled on the withdrawal of the license application.

With $32 billion collected from power companies for the project, and $12 billion spent, the federal government still had $27 billion left. In 2012, Senator Lamar Alexander suggested a bill to give three-fourths of that money back to customers and the rest to companies for storage improvements.

In March 2015, Senator Lamar Alexander introduced a bill to create an independent Nuclear Waste Administration. This new group would develop storage and disposal facilities. Building these facilities would need the agreement of affected states, local areas, and tribal governments. The goal was to open a pilot storage facility by 2021 and a permanent repository by the end of 2048. This bill did not pass.

As of September 30, 2021, the Nuclear Waste Fund had an investment value of $52.4 billion.

Recent Laws (2017–2019)

On March 15, 2017, the Trump Administration asked Congress for $120 million to restart work on Yucca Mountain. This money would also be used to create a temporary storage program. The project aimed to bring nuclear waste from across the United States to Yucca Mountain. However, the Senate refused this budget proposal. Although his administration had asked for money, President Donald Trump later said in October 2018 that he opposed using Yucca Mountain for dumping, agreeing with "the people of Nevada."

On May 11, 2018, a bill (H.R. 3053) was approved in the House of Representatives by a vote of 340–72. This bill told the DOE to restart the licensing process for Yucca Mountain. It would also transfer land to the DOE and make it easier to fund the project. The bill aimed to bring together waste from 121 locations in 39 states. All Nevada representatives opposed the bill.

The Hill newspaper noted that the bill had wide support from lawmakers who wanted nuclear waste moved out of their districts to Yucca Mountain. Nevada representatives, like Dina Titus, called it the "Screw Nevada 2.0" bill. Titus proposed an amendment that would have required long-term storage to be in places that agreed to it, but the House rejected it.

In June 2018, the Trump administration and some members of Congress again suggested using Yucca Mountain, but Nevada Senators continued to oppose it. By early 2019, the use of Yucca Mountain was in "political limbo" due to the strong opposition. In January 2019, a group of scientists suggested including Yucca Mountain as a possible site, but only with a process where local communities had a say.

Officials at the Nevada National Security Site said in April 2019 that their Device Assembly Facility was safe from earthquakes. However, Nevada officials claimed that earthquake activity in the region made it unsafe for storing nuclear waste. In April 2019, the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported that Nevada Democrats in the House were trying to block transfers of plutonium into the state.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |