Élisabeth of France facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Élisabeth of France |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princess of France | |||||

Portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (circa 1782)

|

|||||

| Born | 3 May 1764 Palace of Versailles, Versailles, Kingdom of France |

||||

| Died | 10 May 1794 (aged 30) Place de la Révolution, Paris, French First Republic |

||||

| Burial | Cimetière des Errancis, Paris, France (first) Catacombs of Paris (final) |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Louis, Dauphin of France | ||||

| Mother | Duchess Maria Josepha of Saxony | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Coat of arms |

|||||

Élisabeth Philippe Marie Hélène of France (born May 3, 1764 – died May 10, 1794), also known as Madame Élisabeth, was a French princess. She was the youngest child of Louis, Dauphin of France, and Duchess Maria Josepha of Saxony. She was also the sister of King Louis XVI. Élisabeth's father, the Dauphin, was the son and heir of King Louis XV. Élisabeth stayed with her brother and his family during the French Revolution. She was executed at age 30 in Paris during the Reign of Terror, a very dangerous time. The Catholic Church sees her as a martyr, and she was declared a Servant of God by Pope Pius XII.

Contents

Early Life of Princess Élisabeth

Élisabeth Philippe Marie Hélène was born on May 3, 1764, at the Palace of Versailles. She was the youngest child of Louis, Dauphin of France, and Marie-Josèphe of Saxony. Her grandparents were King Louis XV of France and Queen Maria Leszczyńska. As the king's granddaughter, she was known as a Petite-fille de France.

In 1765, her father died suddenly. Her oldest surviving brother, Louis-Auguste (who later became Louis XVI), became the new Dauphin, meaning the heir apparent to the French throne. Their mother, Marie Josèphe, died in March 1767 from tuberculosis. This made Élisabeth an orphan at just two years old. Her older siblings were Louis-Auguste, Louis Stanislas, Charles Philippe, and Marie Clotilde of France.

Élisabeth and her older sister, Clotilde, were raised by Madame de Marsan, who was the governess for the royal children. The sisters had very different personalities. Élisabeth was described as "proud, stubborn, and strong-willed." Clotilde, however, was seen as "kind and easy to guide." They received the usual education for princesses, focusing on skills, religion, and good behavior. Clotilde enjoyed her studies. They learned botany, history, geography, and religion. They moved with the court between royal palaces, spending their days studying, walking in the park, and riding in the forest.

At first, Élisabeth didn't like to study. She would say that "Princes always had people whose job it was to think for them." She was also impatient with her staff. Madame de Marsan, who found Élisabeth difficult, preferred Clotilde. This made Élisabeth jealous. Their relationship got better when Élisabeth became ill. Clotilde insisted on taking care of her. During this time, Clotilde taught Élisabeth the alphabet and helped her find an interest in religion. This changed Élisabeth's personality a lot. Clotilde became her sister's friend, teacher, and advisor. After this, Élisabeth got a new tutor, Marie Angélique de Mackau. She was firm but kind. Under her teaching, Élisabeth made good progress in her studies and became softer in personality. Her strong will was now used for religious principles.

In 1770, her oldest brother, the Dauphin, married Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, who was better known as Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette found Élisabeth delightful. She showed openly that she liked Élisabeth more than Clotilde, which caused some issues at court.

Life as a Princess

On May 10, 1774, her grandfather, King Louis XV, died. Her older brother Louis-Auguste became King Louis XVI.

In August 1775, her sister Clotilde left France to marry the Crown Prince of Sardinia. Their farewell was very emotional. Élisabeth found it hard to let go of Clotilde. Queen Marie Antoinette wrote about Élisabeth:

"My sister Élisabeth is a charming child. She is smart, has character, and is very graceful. She showed great emotion, far beyond her age, when her sister left. The poor little girl was heartbroken. Since her health is delicate, she became ill and had a severe nervous attack. I admit to my dear mother that I fear I am becoming too attached to her. I see, from my aunts' example, how important it is for her happiness not to remain an old maid in this country."

Becoming an Adult

On May 17, 1778, Élisabeth officially became an adult. She left the children's quarters and got her own royal household. This was at the wish of her brother, the King. She was put under the care of Diane de Polignac as her maid of honor and Bonne Marie Félicité de Sérent as her lady-in-waiting.

There were several attempts to arrange a marriage for her. First, she was suggested to marry Jose, Prince of Brazil. She didn't object, but was reportedly relieved when the talks stopped.

Next, she received a proposal from the Duke of Aosta (who would later become Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia). He was the brother of the Crown Prince of Savoy and her sister Clotilde's brother-in-law. However, the French court didn't think it was proper for a French princess to marry someone of lower status than a king or an heir to a throne. So, the marriage was refused.

Finally, a marriage was suggested between her and her sister-in-law's brother, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. He had liked her when he visited France the year before. He said he was attracted by her "lively mind and kind character." But, a group at court that was against Austria thought an alliance between France and Austria was bad for France. By 1783, these plans were stopped, and no more marriage suggestions were made. Élisabeth herself was happy not to marry. Marrying a foreign prince would mean leaving France. She said: "I can only marry a King's son, and a King's son must rule over his father's kingdom. I would no longer be French. I don't want to stop being French. It's much better to stay here near my brother's throne than to go to another."

Madame Élisabeth didn't have a big royal role before the Revolution. She saw the royal court as too focused on luxury and a threat to her morals. She tried to stay away from it. She only attended court when she absolutely had to, or when the king or queen specifically asked her. When she became an adult and had her own household, she decided to protect herself from court life. She continued to follow the rules her governesses and tutors had taught her. She spent her days in religious devotion, studying, riding, and walking. She only socialized with her trusted ladies and her aunts.

She often visited her aunt, Louise of France, at the Carmelite convent. The king was a bit worried she might become a nun. He once told her, "I want nothing more than for you to visit your aunt, as long as you don't follow her example: Élisabeth, I need you." Élisabeth strongly believed in absolute monarchy. She had great respect for her brother the king and felt it was her duty to stand by him. She was also very close to her second brother, the Count of Provence. She said he was "the best advisor and the most charming storyteller." Her youngest brother, the Count of Artois, was different from her. She sometimes gave him "loving lectures" for his scandals, but he came to admire her.

Her relationship with Queen Marie Antoinette was complex because they were quite different. Marie Antoinette reportedly found Élisabeth delightful when she first joined the court as an adult. Élisabeth, however, was close to her aunts, the Mesdames de France. These aunts were against the queen and her informal changes to court life. Élisabeth shared this view. As a monarchist, she thought the queen's disregard for royal rules was a threat to the monarchy. She once said that if rulers spent too much time with common people, the people would see that "the Queen was only a pretty woman, and they would soon conclude that the King was merely the first among officials." She tried to criticize the queen's behavior, but she asked her aunt Madame Adélaïde to do it for her. Despite these differences, she sometimes visited Marie Antoinette at the Petit Trianon. There, they would fish, watch cows being milked, and welcome the king and his brothers for supper. She also took part in one of the queen's amateur theater shows. She became very fond of the king and queen's children, especially the first dauphin and Marie Thérèse of France. Élisabeth became the godmother of Sophie Hélène Beatrix of France in 1786. That same year, she attended the 100-year celebration of St. Cyr, a school she was very interested in.

In 1781, the king gave her Montreuil, a private estate near Versailles. The queen presented it to her, saying: "My sister, you are now at home. This place will be your Trianon." The king didn't let her spend nights at Montreuil until she was twenty-four. But she usually spent her whole days there, from morning Mass until she returned to Versailles to sleep. At Montreuil, she followed a strict schedule. Her days were divided into hours for studying, exercising (riding or walking), dinner, and prayers with her ladies-in-waiting. This schedule was inspired by her childhood governesses. Élisabeth was interested in gardening and helped the poor in the nearby village of Montreuil. Her former tutor, Lemonnier, was her neighbor at Montreuil. She made him her almoner, meaning he helped her give charity in the village. She imported cows from Switzerland and hired a Swiss man named Jacques Bosson to manage them. She also brought his parents and his cousin-bride Marie to Montreuil. She arranged for Marie to marry him and become her milkmaid. The Bosson family managed her farm at Montreuil, producing milk and eggs that she gave to the poor children of the village.

Élisabeth was interested in politics and strongly supported absolute monarchy. She attended the opening of the National Assembly at Versailles on February 22, 1787. She wondered what the Assembly would achieve. She felt that the King was sincere in asking for advice, but doubted if the Assembly would be as honest. She also noted the Queen's pensive mood and her own differing views, stating, "She is an Austrian. I am a Bourbon." She had a feeling that "all this will turn out badly." She added, "intrigues tire me. I love peace and rest. But I will never leave the King while he is unhappy."

The French Revolution

Élisabeth and her brother Charles-Philippe, Comte d'Artois, were the most conservative members of the royal family. Unlike Artois, who left France on July 17, 1789, after the storming of the Bastille, Élisabeth refused to leave. She stayed even when the serious events of the French Revolution became clear.

On October 5, 1789, Élisabeth saw the Women's March on Versailles from Montreuil. She immediately returned to the Palace of Versailles. She advised the king to strongly stop the riot instead of negotiating. She also suggested the royal family move to a town further from Paris to avoid being influenced by different groups. Her advice was not taken by Necker, and she went to the queen's rooms. She was not harmed when the crowd stormed the palace to try and harm the queen. When the crowd demanded the king return to Paris, and Lafayette advised him to agree, Élisabeth tried to convince the king otherwise. She said: "Sire, it is not to Paris you should go. You still have loyal soldiers, faithful guards, who will protect you. But I beg you, my brother, do not go to Paris."

Élisabeth went with the royal family to Paris. She chose to live with them in the Tuileries Palace instead of with her aunts Adélaïde and Victoire at the Château de Bellevue. The day after they arrived, Madame de Tourzel said the royal family was woken by large crowds outside. Every family member, "even the Princesses," had to show themselves to the public wearing the national cockade (a revolutionary symbol).

In the Tuileries, Élisabeth lived in the Pavillon de Flore. She was first on the first floor next to the queen. But after some fish market women climbed into her apartment through the windows, she swapped with the Princesse de Lamballe to the second floor.

Unlike the queen, Madame Élisabeth had a good reputation with the public. The market women of Las Halles called her the "Sainte Genevieve of the Tuileries." Life at the Tuileries court was quiet. Élisabeth had dinner with the royal family, worked on a tapestry with the queen after dinner, and had supper with the count and countess of Provence every evening. She also continued to manage her property in Montreuil through letters. She wrote many letters to friends both in and outside France, especially her exiled brothers and her friend Marie-Angélique de Bombelles. These letters still exist and show her political views.

In February 1791, she chose not to leave France with her aunts Adélaïde and Victoire. She wrote in a letter: "I didn't think it was my duty to take this step, and that's what decided me. But believe that I will never betray my duty or my religion, nor my affection for those who alone deserve it, and with whom I would give the world to live."

Escape Attempt to Varennes

In June 1791, she went with the royal family on their unsuccessful escape attempt. They were stopped at Varennes and forced to return to Paris. During the journey, Madame de Tourzel pretended to be a Baroness de Korff. The king acted as her valet, the queen as her maid, and Élisabeth as the children's nurse.

She didn't lead the escape, but she played a role on their way back to Paris. Soon after leaving Epernay, three representatives from the Assembly joined them: Barnave, Pétion, and La Tour-Maubourg. Barnave and Pétion rode inside the carriage with the family. During the journey, Élisabeth spoke to Barnave for several hours. She tried to explain why the king had tried to escape and his views on the revolution.

Élisabeth later wrote about the journey to Marie-Angélique de Bombelles: "Our journey with Barnave and Pétion was very funny. You probably think we were in agony! Not at all. They behaved very well, especially Barnave, who is very smart, and not fierce as people say. I started by frankly telling them my opinion of their actions, and after that, we talked for the rest of the journey as if we weren't involved in the matter. Barnave saved the Royal Guards who were with us, whom the National Guard wanted to kill when we arrived here."

After their return, the king, queen, and dauphin (and his governess Tourzel) were watched closely. But no guards were assigned to watch the king's daughter or sister. Élisabeth was actually free to leave whenever she wanted. She chose to stay with her brother and sister-in-law. According to Tourzel, she was "their comfort during their captivity. Her care for the King and Queen and their children always increased as their troubles grew." She was urged by a friend to join her aunts in Rome, but she refused. She said: "There are certain situations where one cannot decide for oneself, and such is mine. The path I should follow is so clearly marked by Providence that I must remain faithful to it."

Events of 1792

On February 20, 1792, Élisabeth went with the queen to the Italian Theatre. This was the last time the queen was applauded in public during such a visit. Élisabeth also attended the celebrations after the king signed the new constitution and the Federation celebration on July 14, 1792. The new constitution led her exiled brothers to plan a French exile government. Élisabeth secretly informed her brother, the Count of Artois, about the political changes. She unsuccessfully opposed the king's approval of a law against priests who refused to take an oath to the new constitution.

Élisabeth and Marie Antoinette were also visited by slave owners from Saint Domingue. They had come to ask the king for protection against a slave rebellion. Élisabeth told them: "Gentlemen, I have deeply felt the misfortunes that have happened in the Colony. I sincerely share the interest the King and Queen have in it, and I ask you to assure all the Colonists of this."

During the Demonstration of 20 June 1792 at the Tuileries Palace, Élisabeth showed great courage. She was famously mistaken for the queen for a short time. She was in the king's room during the event and stayed by his side. When the demonstrators forced the king to wear the revolutionary red cap, Élisabeth was mistaken for the queen. Someone warned her: "You don't understand, they take you for the Austrian." She famously replied: "Oh, I wish it were so! Don't tell them, save them from a greater crime." She pushed aside a bayonet pointed at her, saying: "Be careful, sir. You might wound someone, and I'm sure you would be sorry." When a royalist man trying to protect the king fainted, she reached him and helped him with her smelling salts. After this event, some demonstrators actually said that the failed attack on the royal family was due to Élisabeth's brave behavior. A female demonstrator reportedly said: "There was nothing to be done today; their good St. Genevieve was there."

On August 10, 1792, when rebels attacked the Tuileries, the king and queen were advised to leave the palace and seek safety in the Legislative Assembly. This was because the palace could not be defended. When Élisabeth heard this, she asked: "Monsieur Roederer, will you guarantee the lives of the King and Queen?" He replied: "Madame, we guarantee that we will die by their side; that is all we can guarantee." The royal family, including Élisabeth, then left the palace for the National Assembly. One witness described Élisabeth as "calm and resigned, religion inspired her."

When Élisabeth saw the crowd, she reportedly said: "All those people are misled. I desire their conversion, but not their punishment."

Élisabeth was described as calm in the Assembly, where she later saw her brother lose his throne. She followed the family to the Feuillants, where she shared a room with her nephew, Tourzel, and Lamballe. The whole family was moved to the Temple Tower three days later. Before leaving the Feuillants, Élisabeth told Pauline de Tourzel: "Dear Pauline, we know your discretion and your loyalty to us. I have a very important letter that I want to get rid of before leaving here. Help me make it disappear." They tore up an eight-page letter, but taking too long, Pauline swallowed the pages for her.

Imprisonment in the Temple

After the former king was executed on January 21, 1793, and her nephew, the young "Louis XVII", was separated from the family on July 3, Élisabeth was left with Marie Antoinette and Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, Madame Royale, in their apartment in the Tower. The former queen was taken to the Conciergerie prison on August 2, 1793. When her sister-in-law was removed, both Élisabeth and her niece tried unsuccessfully to follow her. However, they initially stayed in touch with Marie Antoinette through a servant.

Marie Antoinette was executed on October 16. Her last letter, written on the day of her execution, was addressed to Élisabeth, but it never reached her.

Élisabeth and Marie-Thérèse were not told about Marie Antoinette's death. On September 21, they lost their privilege of having servants. This meant their ability to send secret letters to the outside world was also lost. Élisabeth focused on her niece, comforting her with religious words about martyrdom. She also protested against how her nephew was being treated, but without success. Marie-Thérèse later wrote about her: "I feel I have her nature . . . [she] treated me and cared for me as her daughter, and I, I honored her as a second mother."

Trial and Execution

Élisabeth was not seen as dangerous by Robespierre at first. The original plan was to send her away from France. An order from August 1, 1793, which called for Marie Antoinette's trial, actually stated that Élisabeth should not be tried but exiled.

However, Hébert insisted on her execution. On May 9, 1794, Élisabeth, called only "sister of Louis Capet," was moved to the Conciergerie prison. She hugged Marie-Thérèse and promised her she would return. When a commissary said she would not return, she told Marie-Thérèse to be brave and trust in God. Two hours later, she was brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal in the Conciergerie for her first questioning.

She was accused of being part of Marie Antoinette's secret meetings. She was also accused of talking with enemies of France, including her exiled brothers, and planning against the safety of the French people. Other accusations included giving money to French people who had left the country (émigrés) to help them fight France by selling her diamonds. She was also accused of knowing about and helping with the king's Flight to Varennes. Finally, she was accused of encouraging royal troops to fight during the events of August 10, 1792, to cause a massacre of the people attacking the palace.

Élisabeth stated that Marie Antoinette had not held secret meetings. She said she only knew and had contact with friends of France, and had no contact with her exiled brothers since she left the Tuileries. She denied giving money to émigrés. She also said she didn't know about the Flight to Varennes beforehand and that its purpose was not to leave the country, but only for the king to rest in the countryside. She said she went with her brother because he ordered her to. She also denied visiting the Swiss Guard with Marie Antoinette the night before August 10, 1792.

After the questioning, she was taken to a single cell. She refused a public lawyer. However, a lawyer named Claude François Chauveau-Laofarde was called, supposedly by her. He was not allowed to see her that day. He was told she wouldn't be tried for some time, so there would be plenty of time to talk. But, she was actually tried immediately the next morning. So, Chauveau-Laofarde had to defend her without having spoken to her first.

Élisabeth was tried with 24 other people accused of being her accomplices. She was placed in a visible spot during the trial. She was reportedly dressed in white and attracted a lot of attention. She was described as calm and comforting to the others.

The jury found Élisabeth and all 24 co-accused guilty. The Tribunal then sentenced them to death by guillotine the next day. One of her co-accused was spared because she was pregnant.

When she left court, a prosecutor remarked that she had not complained. The president replied: "Why should Élisabeth of France complain? Have we not today given her a court of aristocrats worthy of her? There will be nothing to stop her from imagining herself still in the salons of Versailles when she sees herself, surrounded by this loyal nobility, at the foot of the holy guillotine."

After her trial, Élisabeth joined the other prisoners waiting for their execution. She asked for Marie Antoinette. One of the female prisoners told her, "Madame, your sister has suffered the same fate that we ourselves are about to undergo."

She reportedly comforted and strengthened the other prisoners with religious words and her own calm example.

Élisabeth was executed along with the 23 men and women who had been tried and sentenced with her. She reportedly talked with two women on the way. In the cart taking them to their execution, and while waiting her turn, she helped several of them through the difficult time. She encouraged them and recited a psalm until it was her turn. Near the Pont Neuf, the white scarf covering her head blew off. She was the only one with her head uncovered, so she attracted special attention. Witnesses said she was calm throughout the whole process.

At the foot of the guillotine, there was a bench for those waiting. Élisabeth got out of the cart first, refusing the executioner's help. But she was called last, so she watched all the others die. The first woman called bowed to Élisabeth and asked to hug her. Élisabeth agreed. All the women prisoners who followed did the same. The men bowed to her. Each time, she repeated the psalm "De Profundis." She greatly strengthened the spirits of her fellow prisoners, who all acted bravely. When the last person before her, a man, bowed to her, she said, "Courage, and faith in the mercy of God!" Then she stood up for her own turn.

Her execution reportedly caused some emotion among the onlookers. They did not shout "Long live the Republic," which was common. The respect Élisabeth had among the public worried Robespierre, who had not wanted her executed and "feared the effect" of her death.

Her body was buried in a common grave at the Errancis Cemetery in Paris. When the monarchy was restored in France, Élisabeth's remains were placed in the Catacombs of Paris. A medallion representing her is at the Basilica of Saint Denis.

Efforts for Beatification

The process to declare Élisabeth a blessed person began in 1924, but it is not yet finished. In 1953, Pope Pius XII recognized her heroic virtues because of her martyrdom. The princess was declared a Servant of God, and the official process for beatification started on December 23, 1953.

In 2016, Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, Archbishop of Paris, restarted the process for Princess Élisabeth's beatification. In May 2017, he recognized an association of people who support her cause.

On November 15, 2017, Cardinal Vingt-Trois, after talking with the French Bishops and getting approval from Rome, expressed hope that the process would lead to the canonization (being declared a saint) of Princess Élisabeth, sister of Louis XVI.

Historical View

Élisabeth, who turned thirty a week before her death, was executed mainly because she was the king's sister. However, many French revolutionaries believed she supported the very conservative royalist group. There is evidence that she actively supported plans by the Comte d'Artois to bring foreign armies into France to stop the Revolution. In royalist circles, her good private life was much admired. Élisabeth was praised for her kindness, loyalty to her family, and strong Catholic faith. She clearly saw the Revolution as evil and believed that a civil war was the only way to get rid of it.

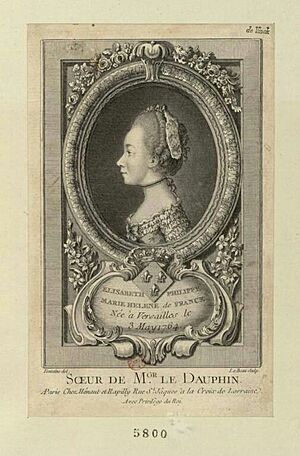

Images for kids

-

Portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (circa 1782)

-

Élisabeth Philippe Marie Helene de France (engraving by Pierre François Léonard Fontaine, c. 1775)

-

Madame Élisabeth, painted in the manner of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

-

Élisabeth de France in 1787 (portrait by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard)

See also

In Spanish: Madame Isabel de Francia para niños

In Spanish: Madame Isabel de Francia para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |