American Civil Liberties Union facts for kids

|

|

| Predecessor | National Civil Liberties Bureau |

|---|---|

| Formation | January 19, 1920 |

| Founders | |

| Type | 501(c)(4) nonprofit organization |

| Purpose | Civil liberties advocacy |

| Headquarters | 125 Broad Street, New York City, U.S. |

|

Region served

|

United States |

|

Membership

|

1.7 million (2024) |

| Deborah Archer | |

|

Executive Director

|

Anthony Romero |

|

Budget

|

$383 million (2024; combined ACLU and Foundation, excludes affiliates) |

|

Staff

|

500 staff attorneys |

|

Volunteers

|

Several thousand attorneys |

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a group in the United States that works to protect the rights and freedoms of all people. These rights, called civil liberties, are guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. The ACLU was founded in 1920 and has offices in every state.

The ACLU helps people in court when they believe their rights have been violated. They might provide lawyers or write legal papers to support a case. The ACLU also works to change laws to better protect everyone's freedoms.

Some of the ACLU's goals include protecting free speech, ending unfair treatment, and making sure the justice system is fair. They also support the right for people to make their own health care choices and believe in the separation of church and state, which means the government should not favor any religion.

Contents

Leadership and Organization

The ACLU is led by a president, who is in charge of the board of directors, and an executive director, who manages the daily work. The main office is in New York City, but most of the ACLU's work is done by its local offices, called affiliates, in each state.

Sometimes, the leaders of the ACLU disagree on what to do. Over the years, they have had big debates. For example, they have argued about whether to defend the rights of business owners, communists, or people protesting wars. These debates show that protecting everyone's rights can be complicated.

How the ACLU Gets Its Funding

The ACLU is a non-profit organization, which means it runs on donations from people and other groups. It does not work to make a profit. The local state offices raise their own money, but the national office sometimes helps smaller affiliates.

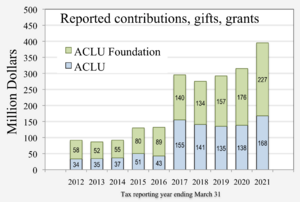

Sometimes, when the ACLU wins a court case against the government, the government has to pay the ACLU's legal fees. For example, the ACLU has won money in cases about religious displays on government property. In 2024, the ACLU received $268 million in donations from its supporters.

What Does the ACLU Stand For?

The ACLU works to protect many different rights found in the U.S. Constitution. Its main goals include defending free speech, equality, and justice for all people.

Protecting Free Speech

When the ACLU started, its main focus was on freedom of speech. The ACLU believes everyone should have the right to speak their mind, even if their ideas are unpopular or offensive. This includes supporting the rights of protesters and even protecting speech that criticizes the government.

Fighting for Equality

The ACLU fights against unfair treatment, also known as discrimination, based on a person's race, gender, religion, or other identities. They have been very active in supporting the rights of women, minority groups, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Reforming the Justice System

The ACLU has long worked to make the criminal justice system fairer. They focus on issues like unfair punishments and making sure everyone has the right to a lawyer. The ACLU also supports the rights of immigrants, whether they are in the country legally or not.

Other Important Issues

The ACLU also takes positions on other rights. For example, it supports a person's right to own a gun under the Second Amendment but also supports some gun safety laws. The organization also strongly supports a woman's right to make her own health care decisions.

History of the ACLU

The ACLU has a long history of defending people's rights, starting in the 1920s and continuing to this day.

The Early Years (1920s)

The ACLU grew out of an earlier group called the National Civil Liberties Bureau (CLB), which was started in 1917 during World War I. The CLB focused on protecting free speech for people who were against the war. In 1920, the group was reorganized and renamed the American Civil Liberties Union.

In the 1920s, the ACLU's main goal was to protect free speech, especially for workers who were trying to form unions. They also famously defended a teacher named John T. Scopes in 1925. Scopes was charged with breaking a Tennessee law that banned teaching evolution in public schools. This case, known as the Scopes Trial, made the ACLU famous across the country.

One of the most important cases for the ACLU in the 1920s was Gitlow v. New York. The Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment's protection of free speech applied to state governments, not just the federal government. This was a huge victory for civil liberties.

Fighting for Rights in the 1930s

In the 1930s, the ACLU expanded its work. It helped pass laws to protect workers' rights to form unions. It also fought against police misconduct and worked to protect the rights of Native Americans and African Americans.

The ACLU also began to fight against censorship. They defended writers and artists whose work was banned for being "obscene." A major victory came in 1933 when a court allowed the book Ulysses by James Joyce to be sold in the U.S.

During this time, the ACLU had a difficult relationship with the Communist Party. While the ACLU defended the free speech rights of communists, the two groups often disagreed. This led to a major debate inside the ACLU, and in 1940, the ACLU voted to ban communists from being leaders in the organization. This decision was very controversial and was later reversed in 1968.

World War II and the Cold War (1940s–1950s)

During World War II, the U.S. government took actions that limited civil liberties. One of the most serious was forcing over 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps. The ACLU was divided on how to respond. Some local offices wanted to challenge the government's actions in court, but the national leaders were more hesitant. This period is seen as a difficult time in the ACLU's history.

After the war, the Cold War began, and there was a lot of fear about communism in the United States. This period, known as McCarthyism, led to many people losing their jobs or being jailed for their political beliefs. The ACLU was again divided on how to act but eventually became a strong defender of those accused of being communists.

In 1954, the Supreme Court made a historic decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The ACLU supported this case and played a key role in the growing civil rights movement.

The Civil Rights Era (1960s)

The 1960s was a time of great change in America, and the ACLU was at the center of it. The organization's membership grew, and it became more involved in fighting for racial justice, protecting protesters, and expanding individual rights.

The ACLU worked closely with groups like the NAACP to fight segregation in the South. They provided lawyers for students who participated in sit-ins and for the Freedom Riders, who challenged segregation on buses.

The ACLU also won several major Supreme Court cases during this decade.

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): This case established that people who cannot afford a lawyer must be given one in criminal cases.

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966): This case led to the famous "Miranda rights," which police must read to suspects before questioning them.

- Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969): This case protected the free speech rights of students in schools, as long as it doesn't disrupt education.

The ACLU also fought against the Vietnam War, defending people who protested the war and burned their draft cards. This was controversial and led some to say the ACLU was becoming a political organization.

New Challenges (1970s)

In the 1970s, the ACLU began to focus on new areas of civil liberties. It started projects to protect the rights of women, prisoners, students, and gay and lesbian people.

The Women's Rights Project, co-founded by future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, won important cases that fought gender discrimination. The ACLU also played a key role in the landmark 1973 Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade, which established a woman's right to make decisions about her own body.

In 1973, the ACLU was the first national organization to call for the impeachment of President Richard Nixon because of the Watergate scandal. This move was controversial and led to more criticism that the ACLU was too political.

One of the most famous and difficult cases for the ACLU was the Skokie case in 1977. The ACLU defended the right of a neo-Nazi group to march in Skokie, Illinois, a town with many Holocaust survivors. The ACLU argued that free speech must be protected for everyone, even for those with hateful views. The decision caused many members to leave the ACLU, but the organization stood by its principles.

Recent History (1980s–Today)

In recent decades, the ACLU has continued to tackle new and challenging issues. During the 1980s, it fought against efforts to bring prayer into public schools.

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the ACLU challenged government policies like the Patriot Act, arguing that they violated privacy and other rights in the name of national security.

In the 21st century, the ACLU has been very active in defending LGBTQ+ rights, including the right to same-sex marriage. They have also been involved in debates about free speech on the internet, government surveillance, and immigration policies.

Following the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, the ACLU saw a huge increase in donations and members. The organization filed many lawsuits against the Trump administration, particularly over its immigration policies. This has led some critics to say the ACLU has become more of a partisan political group than a neutral defender of rights. The ACLU says it is simply continuing its mission to defend the Constitution for everyone.

Images for kids

-

Norman Thomas was an early leader of the ACLU.

-

The ACLU defended writer H. L. Mencken when he was arrested for distributing a banned magazine.

-

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was removed from the ACLU board in 1940 because of her political beliefs but was welcomed back after her death.

-

In the 1950s, the ACLU chose not to defend singer Paul Robeson, a decision that was later criticized.

-

The ACLU was the first national organization to call for the impeachment of President Richard Nixon.

-

The ACLU defended Oliver North in 1990, arguing his trial was unfair.

See also

In Spanish: Unión Estadounidense por las Libertades Civiles para niños

In Spanish: Unión Estadounidense por las Libertades Civiles para niños

- American Civil Rights Union

- British Columbia Civil Liberties Association

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association

- Common Cause

- Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)

- Institute for Justice

- Liberty, a British equivalent

- List of court cases involving the American Civil Liberties Union

- National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee

- Political freedom

- Southern Poverty Law Center

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |