Pope Alexander VI facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pope Alexander VI |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

|

|

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 11 August 1492 |

| Papacy ended | 18 August 1503 |

| Predecessor | Innocent VIII |

| Successor | Pius III |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1468 |

| Consecration | 30 October 1471 |

| Created Cardinal | 17 September 1456 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Roderic de Borgia (Rodrigo Borja) |

| Born | 1431 Xàtiva, Kingdom of Valencia, Crown of Aragon |

| Died | 18 August 1503 (aged 72) Rome, Papal States |

| Buried | Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli, Rome |

| Nationality | Aragonese – Spanish |

| Denomination | Catholic (Roman Rite) |

| Parents |

|

| Children |

|

| Previous post |

|

| Education | University of Bologna |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other Popes named Alexander | |

Pope Alexander VI (1431 – 18 August 1503) was born Rodrigo de Borja. He was the leader of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1492 until his death in 1503. Rodrigo came from the important Borgia family in Xàtiva, which was part of the Crown of Aragon (now Spain).

Rodrigo studied law at the University of Bologna. He became a deacon and a cardinal in 1456. This happened after his uncle was elected Pope Callixtus III. A year later, Rodrigo became the vice-chancellor of the Catholic Church. He worked for the next four popes, gaining a lot of power and wealth. In 1492, Rodrigo was chosen as pope and took the name Alexander VI.

Pope Alexander VI's official papers, called papal bulls, in 1493, confirmed Spain's rights in the New World. This was after Christopher Columbus discovered new lands in 1492. During the Second Italian War, Alexander VI supported his son Cesare Borgia. Cesare was a military leader for the French king. Alexander's main goal in foreign policy was to help his family gain power and wealth.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Rodrigo de Borja was born in 1431 in Xàtiva, a town near Valencia. This area is now part of Spain. He was named after his grandfather, Rodrigo Gil de Borja y Fennolet. His parents were Jofré Llançol i Escrivà and Isabel de Borja y Cavanilles. He had a younger brother named Pedro.

The family name was Llançol in the Valencian language and Lanzol in Castillian. Rodrigo changed his family name to Borja (or Borgia in Italian) in 1455. This was after his mother's uncle, Alonso de Borja, became Pope Callixtus III.

How Rodrigo Became a Cardinal

Rodrigo de Borja's career in the Church started in 1445 when he was 14 years old. His powerful uncle, Alfons Cardinal de Borja, appointed him as a sacristan at the Cathedral of Valencia. His uncle had become a cardinal the year before.

In 1448, Rodrigo became a canon at several cathedrals. His uncle convinced Pope Nicholas V to let Rodrigo hold these positions and receive income even when he was not there. This allowed Rodrigo to travel to Rome. In Rome, Rodrigo studied under a humanist teacher. He then studied law at the University of Bologna and became a highly skilled lawyer.

When his uncle, Alfons Cardinal de Borja, became Pope Callixtus III in 1455, Rodrigo received more important roles in the Church. This practice of giving positions to family members was common at the time. In 1455, Rodrigo took over his uncle's job as bishop of Valencia. The next year, he became a deacon and a cardinal-deacon.

In 1457, Pope Callixtus III sent Cardinal de Borja to Ancona to stop a revolt. Rodrigo succeeded in this mission. His uncle then made him vice-chancellor of the Holy Roman Church. This job was very powerful and brought in a lot of money. Rodrigo held this position for 35 years until he became pope in 1492.

Rise to Power and Influence

In the papal election of 1458, Rodrigo Borgia was too young to become pope himself. So, he worked to support a cardinal who would let him keep his job as vice-chancellor. Borgia helped elect Cardinal Piccolomini, who became Pope Pius II. The new pope allowed Borgia to keep his chancellorship and gave him more profitable church positions.

In 1463, Borgia helped Pope Pius fund a new crusade. However, Pope Pius II died before leading the crusade. Borgia then needed to make sure another ally was elected pope to keep his important position.

In the election of 1464, Borgia's friend Pietro Barbo became Pope Paul II. Borgia remained in a good position with the new pope and kept all his roles, including vice-chancellor. After the election, Borgia got sick with the plague but recovered. Pope Paul II died suddenly in 1471.

Borgia had become wealthy and powerful enough to try to become pope in the 1471 election. However, there were only three non-Italian cardinals, making it very difficult for him to be chosen. So, Borgia again focused on helping to choose the next pope. He helped elect Francesco della Rovere, who became Pope Sixtus IV. Sixtus IV was a religious monk who did not have many political connections in Rome. He seemed like a good choice to reform the Church and someone Borgia could influence.

Pope Sixtus IV rewarded Borgia for his support. He promoted him to cardinal-bishop and made him the Cardinal-Bishop of Albano. This required Borgia to become a priest. Borgia also received another profitable church position and remained vice-chancellor.

Later that year, the pope sent Borgia to Spain to negotiate a peace treaty between Castile and Aragon. He also asked Borgia to get their support for another crusade. In 1472, Borgia was also made the papal chamberlain. Borgia arrived in Aragon and met with King Juan II and Prince Ferdinand. The pope allowed Cardinal Borgia to decide whether to approve the marriage between Ferdinand and his cousin Isabella of Castile. Borgia approved the marriage. The couple then asked Borgia to be the godfather of their first son. This marriage was very important for uniting Castile and Aragon into Spain. Borgia also helped bring peace to Castile and Aragon. He gained the favor of the future King Ferdinand, who would help the Borgia family in Aragon.

Borgia returned to Rome the next year. He barely survived a storm that sank a nearby ship carrying 200 people from his household. In 1476, Pope Sixtus made Borgia the cardinal-bishop of Porto. By 1483, Borgia had become the wealthiest cardinal. He also became the Dean of the College of Cardinals that year. In 1484, Pope Sixtus IV died, meaning another election for Borgia to influence.

Borgia was rich and powerful enough to try to become pope himself. But he faced competition from Giuliano della Rovere, the late pope's nephew. Della Rovere had many supporters because Sixtus had appointed many of the cardinals. Borgia tried to get votes through bribery and by using his connections to Naples and Aragon. However, many Spanish cardinals were not at the election, and della Rovere's group had a huge advantage. Della Rovere chose to support Cardinal Cibo. Cibo then made a deal with the Borgia group. Borgia again helped choose the pope, supporting Cardinal Cibo, who became Pope Innocent VIII. Borgia kept his job as vice-chancellor. He had successfully held this position through five popes and four elections.

In 1485, Pope Innocent VIII wanted Borgia to become the Archbishop of Seville. However, King Ferdinand II wanted this job for his own son. In response, Ferdinand angrily took over Borgia's lands in Aragon and put Borgia's son Pedro Luis in prison. Borgia fixed the problem by turning down the appointment.

Pope Innocent, urged by his ally Giuliano della Rovere, decided to declare war against Naples. But Milan, Florence, and Aragon supported Naples. Borgia led the cardinals who opposed this war. King Ferdinand rewarded Borgia by making his son Pedro Luis the Duke of Gandia. He also arranged a marriage between his cousin Maria Enriquez and the new duke. This connected the Borgia family directly to the royal families of Spain and Naples. While Borgia gained Spain's favor, he was against the pope and the della Rovere family. As part of his opposition to the war, Borgia tried to stop an alliance between the papacy and France. These talks failed, and in July 1486, the pope gave up and ended the war.

In 1488, Borgia's son Pedro Luis died, and Juan Borgia became the new Duke of Gandia. In 1492, Pope Innocent VIII died. Since Borgia was 61, this was likely his last chance to become pope.

Becoming Pope Alexander VI

When Pope Innocent VIII died on July 25, 1492, there were three main candidates to become pope. These were the 61-year-old Borgia, Ascanio Sforza, and Giuliano della Rovere.

It was rumored that Borgia bought the most votes, and that Sforza was bribed with a lot of silver. However, records show that Borgia was in the lead from the start. The rumors of bribery began after the election when positions were given out. Other candidates were also willing to offer bribes.

In the first round of voting, Borgia received seven votes. Borgia convinced Sforza to join his side by promising him the job of vice-chancellor and other benefits. With Sforza's help, Borgia's election was certain. Borgia was elected on August 11, 1492, and took the name Alexander VI. Many people in Rome were happy with their new pope. He was known as a generous and skilled administrator who had served as vice-chancellor for decades.

Early Years as Pope

At first, Pope Alexander VI was very strict about justice and good government. However, he soon started giving gifts and positions to his relatives using Church money and at the expense of his neighbors. His son, Cesare Borgia, who was seventeen and a student, was made Archbishop of Valencia. His other son, Giovanni Borgia, inherited the Spanish Dukedom of Gandia, which was the Borgia family's original home in Spain.

Pope Alexander wanted to create new lands for Giovanni and his son Gioffre (also known as Goffredo) from the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples. This plan caused conflict with Ferdinand I of Naples and Cardinal della Rovere. Della Rovere strengthened his position in his bishopric of Ostia. Alexander then formed an alliance against Naples on April 25, 1493, and prepared for war.

Ferdinand allied with Florence, Milan, and Venice. He also asked Spain for help. Spain wanted to stay on good terms with the papacy to get rights to the recently discovered New World. Alexander, in an official paper called the bull Inter caetera on May 4, 1493, divided the new lands between Spain and Portugal. This division became the basis for the Treaty of Tordesillas.

French Involvement in Italy

Pope Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his power. He sought help from Charles VIII of France (1483–1498). Charles was allied with Ludovico "il Moro" Sforza, who was the ruler of Milan. Ludovico needed French support to make his rule official. Since King Ferdinand I of Naples was threatening to help the rightful duke, Alexander encouraged the French king to conquer Naples.

However, Alexander always looked for chances to help his family. He then made peace with Naples in July 1493. He strengthened this peace by arranging a marriage between his son Gioffre and Doña Sancha, another granddaughter of Ferdinand I. To gain more control over the College of Cardinals, Alexander created 12 new cardinals. This caused a lot of talk. Among the new cardinals was his own son Cesare, who was only 18 years old.

On January 25, 1494, Ferdinand I died, and his son Alfonso II became king. Charles VIII of France then formally claimed the Kingdom of Naples. Alexander allowed Charles to pass through Rome, supposedly for a crusade against the Ottoman Empire, without mentioning Naples. But when the French invasion became real, Pope Alexander VI became worried. He recognized Alfonso II as king of Naples and formed an alliance with him. In return, Alexander received various lands for his sons in July 1494.

A military plan was put into action to stop the French. A Neapolitan army was to attack Milan, and the fleet was to capture Genoa. Both plans failed. On September 8, Charles VIII crossed the Alps and joined Ludovico il Moro in Milan. The Papal States were in chaos. Charles VIII quickly moved south and arrived in Rome in November 1494.

Alexander tried to gather troops and defend Rome, but his position was weak. When the Orsini family offered to let the French into their castles, Alexander had to make a deal with Charles. On December 31, Charles VIII entered Rome with his troops and his supporters. Alexander feared that Charles might remove him from power. Alexander managed to win over a key French bishop by making him a cardinal. Alexander agreed to send Cesare with the French army to Naples. He also agreed to give Cem Sultan, who was a hostage, to Charles VIII, and to give Charles the city of Civitavecchia on January 16, 1495. On January 28, Charles VIII left for Naples with Cem and Cesare. However, Cesare escaped to Spoleto. The Neapolitan resistance collapsed, and Alfonso II fled. The Kingdom of Naples was conquered very easily.

French Retreat and Papal Power

Soon, other European powers became worried about Charles VIII's success. On March 31, 1495, the Holy League was formed. This alliance included the pope, the emperor, Venice, Ludovico il Moro, and Ferdinand of Spain. The League was supposedly against the Turks, but its real goal was to remove the French from Italy.

Charles VIII was crowned King of Naples on May 12. But a few days later, he began his retreat north. He fought the League at Fornovo and made his way back to France by November. Ferdinand II was put back on the throne in Naples with Spanish help. This expedition showed that Italy was vulnerable to powerful invading forces like France and Spain.

Alexander VI then worked to reduce the power of the great feudal lords and create a more centralized government in the Papal States. He used the French defeat to weaken the Orsini family. From then on, Alexander was able to build a strong power base in the Papal States.

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spanish, died in prison. The Pope took his property. The rest of the Orsini family continued to fight. They defeated the papal troops at Soriano in January 1497. Peace was made with the help of Venice. The Orsini paid 50,000 ducats to get their lands back. The Orsini remained very powerful, and Pope Alexander VI could only rely on his 3,000 Spanish troops. His only successes had been capturing Ostia and getting the Colonna and Savelli cardinals to submit.

Then, a sad event happened for the Borgia family. On June 14, Pope Alexander's son, the Duke of Gandia, disappeared. The next day, his body was found in the Tiber River. Alexander was overcome with sadness. He said that from then on, his only goal would be to reform the Church. Efforts were made to find the killer, but no clear answer was ever found.

The Jubilee Year of 1500

In the Jubilee year 1500, Alexander VI started the tradition of opening a holy door on Christmas Eve and closing it on Christmas Day the following year. After talking with his Master of Ceremonies, Pope Alexander VI opened the first holy door in St. Peter's Basilica on Christmas Eve 1499. Papal representatives opened doors in the other three main basilicas. For this, Pope Alexander had a new opening made in the entrance of St. Peter's and ordered a marble door.

Alexander was carried to St. Peter's. He and his helpers, carrying candles, walked to the holy door. The choir sang a psalm. The pope knocked on the door three times, workers opened it from the inside, and everyone then crossed the doorway to enter a time of reflection and forgiveness. This way, Pope Alexander made this a formal ceremony, starting a long tradition that continues today. Similar ceremonies took place at the other three basilicas.

Alexander also created a special ceremony for closing a holy door. On the Feast of the Epiphany in 1501, two cardinals began to seal the holy door with two bricks, one silver and one gold. Church workers finished sealing it, placing special coins and medals inside the wall.

Views on Slavery

While Spanish explorers used a form of forced labor called "encomienda" on the native peoples in the New World, some popes had spoken against slavery. In 1435, Pope Eugene IV spoke out against slavery in the Canary Islands. He said that anyone involved in the slave trade with native chiefs there would be excommunicated (removed from the Church). A type of indentured servitude was allowed, which was similar to a peasant's duty to his lord in Europe.

After Columbus landed in the New World, the Spanish monarchy asked Pope Alexander to confirm their ownership of these new lands. The official papers issued by Pope Alexander VI, including Inter caetera (May 4, 1493), gave rights to Spain regarding the newly discovered lands in the Americas. These rights were similar to those Pope Nicholas V had given to Portugal earlier.

Some historians believe these papers allowed the enslavement of natives. Others argue that Alexander never approved of slavery. Later popes, like Pope Paul III in 1537 and Pope Gregory XVI in 1839, continued to condemn slavery.

In 1993, the Indigenous Law Institute asked Pope John Paul II to cancel Inter caetera. They also asked for apologies for the historical harm caused. The Parliament of World Religions made a similar request in 1994.

Final Years and Legacy

A new danger appeared from a group of deposed rulers, the Orsini family, and some of Cesare's own military leaders. At first, the papal troops were defeated, and things looked bad for the Borgia family. But a promise of French help quickly forced the group to make peace. Cesare then tricked the leaders at Senigallia and had them killed on December 31, 1502. When Alexander VI heard the news, he tricked Cardinal Orsini into coming to the Vatican and put him in prison, where he died. His property was taken, and many other family members in Rome were arrested. Alexander's son Goffredo Borgia led an expedition and captured their castles. This way, the two powerful Orsini and Colonna families, who had often challenged the pope's authority, were brought under control. The Borgias' power grew.

Cesare then returned to Rome. His father asked him to help Goffredo take the last Orsini strongholds. Cesare was not eager to do this, which annoyed his father. But he eventually marched out, captured Ceri, and made peace with Giulio Orsini.

The war between France and Spain for control of Naples continued. The pope was always involved in secret plans, ready to ally with whichever power offered the best terms. He offered to help Louis XII if Sicily was given to Cesare. Then he offered to help Spain in exchange for Siena, Pisa, and Bologna.

Cesare was preparing for another military trip in August 1503. After he and his father had dinner with Cardinal Adriano Castellesi on August 6, they both became ill with a fever a few days later. Cesare eventually recovered, but the elderly pope did not have much chance.

Many people believe the pope died from malaria, which was common in Rome at the time, or another disease. One official wrote that it was not surprising that Alexander and Cesare both got sick, as the bad air had caused many people in Rome to fall ill.

After a short time, Pope Alexander VI's body was moved from the crypts of St. Peter's. It was placed in the Spanish national church of Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli.

After Alexander VI died, his rival and successor, Julius II, said: "I will not live in the same rooms as the Borgias lived. He disgraced the Holy Church like no one before." The Borgia Apartments remained sealed until the 19th century.

Some people who defend Alexander VI argue that his actions were not unusual for the time period. They say that popes are judged more harshly than kings.

Alexander VI tried to reform the Church. He gathered a group of his most religious cardinals to help. The planned reforms included new rules about selling Church property, limiting cardinals to one diocese, and stricter moral rules for clergy. However, these reforms were not fully put into practice.

Alexander VI was known for supporting the arts. A new style of architecture began in Rome during his time with the arrival of Bramante. Famous artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Pinturicchio all worked for him. He asked Pinturicchio to paint a beautiful set of rooms in the Vatican, which are now known as the Borgia Apartments. He was also very interested in plays.

Besides the arts, Alexander VI also encouraged education. In 1495, he issued an official paper to create King's College, Aberdeen in Scotland. This college is now part of the University of Aberdeen. Alexander VI also approved the University of Valencia in 1501.

Alexander VI treated Jewish people relatively well. After the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain, about 9,000 poor Iberian Jews arrived at the borders of the Papal States. Alexander welcomed them into Rome. He stated that they were "permitted to live their life, free from interference from Christians, to continue in their own rites, to gain wealth, and to enjoy many other privileges." He also allowed Jews expelled from Portugal in 1497 and from Provence in 1498 to immigrate.

Despite the hostility from Julius II, the powerful Roman families and regional rulers were no longer a big problem for the papacy. Julius's successes were built on the foundations laid by the Borgias. Unlike Julius, Alexander rarely went to war unless it was absolutely necessary. He preferred to use negotiation and diplomacy.

Some historians argue that the bad things said about the Borgias were exaggerated by people at the time. This was because they were outsiders who were gaining power at the expense of Italians. Also, they were Spanish, and many felt Spain had too much control in Italy. After Alexander's death, the family lost its influence, so no one had a reason to defend them.

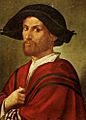

Images for kids

-

Giovanni Borgia, 2nd Duke of Gandia.

-

Portrait of a Gentleman (Cesare Borgia)

-

Presumed portrait of Lucrezia Borgia by Bartolomeo Veneto

-

Gioffre Borgia (1482–1517) Prince of Squillace.

-

Giulia Farnese as – A young Lady and a Unicorn, by Domenichino, c. 1602, from Palazzo Farnese

-

Luisa de Guzmán, Queen consort of Portugal

-

Alexander VI kneeling in front of the Madonna, said to be a likeness of Giulia Farnese.

See also

In Spanish: Alejandro VI para niños

In Spanish: Alejandro VI para niños

- Banquet of Chestnuts

- Birthplace of Pope Alexander VI

- Cardinals created by Alexander VI

- List of popes from the Borgia family

- List of sexually active popes

- Route of the Borgias

- Spanish Empire

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |