American services and supply in the Siegfried Line campaign facts for kids

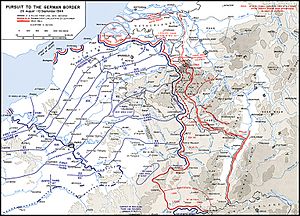

During World War II, American supply efforts were super important in the Siegfried Line campaign. This campaign lasted from mid-September 1944, when American forces chased German armies out of Normandy, until December 1944. That's when the Germans launched a surprise attack called the Ardennes offensive. In August 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the top Allied commander, decided to keep chasing the German forces. He wanted to push them beyond the Seine River and across France and Belgium all the way to Germany. This was different from the original plan, which said they should stop to build up supplies first.

This fast push to the German border really stretched the American supply system. It almost broke! The advance stopped in mid-September because of this. There were big problems with getting supplies through ports and moving them around. This caused many shortages. Some shortages were also due to mistakes in planning and not ordering enough supplies. For example, there wasn't enough winter clothing. People thought the war would end soon, so they didn't order enough warm clothes.

The winter of 1944–1945 in Europe was super cold and wet. American soldiers weren't taught how to avoid cold injuries. Because of this, about 71,000 American soldiers got sick or injured from the cold, like trench foot and frostbite. Also, there weren't enough artillery shells at the start of the campaign. This led to more soldiers getting hurt, delayed battles, and made the war last longer.

Contents

Why was supply a problem?

The fast chase across France

After the Allies landed in Normandy on D-Day (June 6, 1944), the Germans fought hard. The Allies moved slower than planned at first. But then, Operation Cobra started on July 25. This operation helped the American First Army break out of Normandy. The 12th Army Group started on August 1, led by Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley. It included the First Army and the Third Army. The Ninth Army joined later in September.

British General Sir Bernard Montgomery was in charge of all ground forces until September 1. Then, General Dwight D. Eisenhower took direct command. He also took control of the supply and communications groups.

On August 24, Eisenhower decided to keep chasing the Germans. This put a huge strain on the supply system. Between August 25 and September 12, the Allied armies moved very quickly. They covered a distance that was expected to take 350 days in just 19 days! Planners thought only 12 divisions could be supplied past the Seine River. But by September, 16 divisions were there, even if they had fewer supplies than normal. People became too confident that they could always overcome supply problems.

The advance stopped in September. This wasn't because there weren't enough supplies overall. There were still 600,000 tons of supplies in Normandy two months later. The real problem was getting fuel and supplies to the front lines. Railways couldn't be fixed fast enough, and pipelines couldn't be built quickly. Trucks were used as a temporary fix, but there weren't enough of the right kind. Too few heavy trucks were made in the U.S. So, smaller GMC CCKW 2½-ton 6×6 trucks were used for long trips, even though they weren't good for it. Roads also got bad quickly because of heavy military traffic and autumn rains.

Supply problems, especially shortages of food, fuel, ammunition, and spare parts, were serious. They slowed down military operations. But they weren't the only reasons the advance stopped. American forces also faced tough land, bad weather, and stronger German resistance. American forces were spread out. General Hodges, worried about supplies, told his commanders to stop when they met strong resistance. As American forces faced the Siegfried Line defenses, the most important supply changed from fuel to ammunition.

Where were supplies kept?

Supply depots and their challenges

The big supply system planned for the invasion didn't exist in September 1944. The fast advance meant some plans for ports and maintenance areas were dropped. This left the main supply area back in Normandy. Paris would have been a good spot for supplies because it was a major transport hub. But General Eisenhower wanted Paris to be a rest area for soldiers, not a supply base.

So, only small supply depots were set up near Paris. The supply staff looked for places near Antwerp in Belgium, but the British didn't agree. In September, large depots were set up near Liege to support the First and Ninth Armies. Another was near Verdun for the Third Army. These depots started getting supplies directly from ports in Normandy. They became the main places for food, clothing, equipment, and ammunition.

When the port of Antwerp opened in November, a huge amount of supplies arrived. This overwhelmed the depots near Liege and Verdun. To help, new supply areas were set up near Mons and Charleroi. The German Ardennes offensive caused major problems for the supply system. It threatened the main depots. So, shipments to Liege and Verdun were stopped. But ships still had to unload cargo at the port to avoid a global shipping crisis. This meant supplies piled up on the docks and rail lines.

After the attack, new depot areas were set up near Dijon and Nancy. The supply system slowly started to work better, with main, middle, and front-line depots.

What about winter clothes?

New uniforms and problems getting them

Before D-Day, American soldiers in the UK lived like regular soldiers. Looking neat was important. The wool service uniform was worn by staff and off-duty soldiers. But it was hard to keep clean and neat. The M1941 Field Jacket was criticized because it needed frequent washing and looked shabby quickly.

American officers liked the British battledress. It had high-waisted pants and a short jacket that fit snugly. It looked smart and was very durable. It could be scrubbed clean and didn't need ironing. An American version was made in the UK, called the ETO or Eisenhower jacket.

In March 1944, Eisenhower asked for over 4 million ETO jackets. But the wool used in the British design wasn't available in the U.S. So, a different wool was used, which made it less useful as a field uniform. It was also hard to mass-produce.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Quartermaster Corps designed a new winter uniform, the M1943 Uniform. This uniform used layers of clothing. The main piece was a cotton field jacket. It was lighter than older coats but kept soldiers just as warm in cold weather. It was tested in Italy during the Battle of Anzio.

Major General Robert McG. Littlejohn, the ETO quartermaster, didn't like the M1943 jacket. He thought it didn't look "neat and snappy." He said the ETO wouldn't accept it. But the older M1941 jacket was no longer made. So, shipments of the M1943 jacket began in May 1944. He did accept the sweater and new woolen sleeping bags that were part of the M1943 uniform.

For rain protection, Littlejohn ordered 250,000 ponchos. These were better than raincoats because one size fit all. He wanted nylon ponchos, but those were for the Pacific. He also rejected the leather gloves because they made it hard to use a gun. He asked for wool gloves instead. He also wanted "shoepacs," which were rubber boots good for wet conditions. But these were mostly sent to Alaska and North Africa.

Getting winter clothes to soldiers

Soldiers going into Normandy were given summer clothes. Winter clothes were taken away before they left the UK. When the fast chase ended in early September, soldiers had lost or thrown away a lot of equipment. Getting proper winter clothing was now very urgent. Army quartermasters were already warning that it was getting cold at the front.

Winter clothing wasn't a big part of the D-Day plans. The focus was on a summer campaign in Normandy. The plan didn't expect armies to reach cold areas like the Ardennes until May 1945. So, medical plans didn't even mention cold injuries. Few soldiers or officers knew how to prevent them.

Winter clothing was available, but not where it was needed most. Shipping was the main problem. By the end of September, 75 ships full of supplies were waiting to unload in Europe. There weren't enough places for them to dock. This problem continued even after the port of Antwerp opened in November.

Once unloaded, supplies faced delays because the land transport system was overloaded. Of 54,200 tons of clothing and footwear unloaded in September, only 15,400 tons were moved forward. This created a huge backlog. By December, the backlog was 88,600 tons.

Littlejohn suggested reducing food and fuel shipments to make room for winter clothing. He also wanted clothing for some armies to be flown in or brought through smaller ports. But other generals prioritized fuel and ammunition. General Bradley later took blame for this. He said he chose ammunition and gasoline over winter clothing during the race to the Rhine.

Littlejohn tried to work around these low priorities. He sent trucks loaded with warm underwear to the First Army. An LST (Landing Ship, Tank) was used to ship winter clothing to the Ninth Army through less busy ports. Ships carrying food were sent to different ports to free up trains for winter clothing. The Seventh Army even got winter clothing by air. Littlejohn also made a deal for bombers to deliver winter clothing to forward airstrips for the First and Third Armies.

When the Third Army moved to France, they brought their duffel bags. These were stored in Normandy. In September, they were moved forward by truck. But some bags were stolen, and many didn't have blankets or overcoats anymore. The First Army had turned in their duffel bags in the UK. The contents should have been reused, but this process was slow. Infantry divisions got winter clothing first. The First and Third Armies got full issues in early October, though some items like overshoes and raincoats were still short.

The number of blankets per soldier was cut from four to two. This was because sleeping bags were supposed to replace the other two. But only a small number of sleeping bags were delivered. Littlejohn then ordered 4 million blankets. By the end of the year, 2.5 million blankets and 2 million sleeping bags were shipped.

New orders for winter clothing were placed in October to rebuild supplies. These orders included millions of blankets, overcoats, overshoes, shirts, trousers, sweaters, and sleeping bags. This was a huge amount of cargo.

Footwear problems

Figuring out how many replacement items were needed was tricky. For socks, soldiers were supposed to get three pairs of cushion-soled socks and two pairs of wool socks. But cushion-soled socks were often in short supply. In October, the replacement rates for socks were increased. General Eisenhower also suggested that every soldier get a clean pair of socks each day.

According to the ETO Chief Surgeon, General Paul R. Hawley, "the plain truth is that the footwear furnished US troops is, in general, lousy." Most soldiers wore combat boots or service shoes. Service shoes needed canvas leggings, which made foot care harder. Both types of shoes were too tight, especially with thick socks. They also restricted blood flow. Many soldiers only had one pair of shoes, and they weren't waterproof. Dubbin was given to protect the leather, but it didn't make them waterproof.

The Seventh Army got 90,000 shoepacs in time for winter. But the First, Third, and Ninth Armies didn't get theirs until January. When it was clear combat boots weren't good enough, Littlejohn ordered another 500,000 shoepacs.

The shoepacs given to the armies were old types. They were too short for deep water or mud. They also lacked heels and arch supports, and the rubber soles wore out fast. They didn't breathe well, making feet sweat even in cold weather. When it was cold, the inner soles froze, making feet uncomfortable. This led to many foot problems and hospital visits. Soldiers weren't trained enough on how to use them.

Without proper footwear, soldiers made their own solutions. Some wore rubber overshoes with many pairs of socks, or even boots made from army blankets. Only the Seventh Army had enough overshoes. In the Third Army, there was only one pair for every four men in November. Many divisions didn't have enough even by January 1945. Large sizes were hard to find.

Overshoes made it hard to move fast and were difficult to carry. So, soldiers often threw them away before an attack. Older types of overshoes had canvas tops that tore easily and leaked. Newer ones were all rubber.

Health issues

The winter of 1944–1945 in Europe was very cold and wet. In October and November, there was heavy rain. Then, from December to January, temperatures stayed around freezing. American operations had been slow in September and October. But Eisenhower decided that supplies were good enough to start major attacks again. The Third Army began the Battle of Metz in November. The First and Ninth Armies followed. These battles happened on wet and often flooded land.

The weather caused cold injuries. Trench foot was common in wet conditions (October-November). Frostbite was common in colder weather (December-January). But weather wasn't the only reason. Bad clothing and footwear, keeping soldiers on the front lines too long, and poor foot care were also big factors. Five weeks of fighting in November and December caused about 64,000 battle injuries for the 12th Army Group. There were also 12,000 cases of trench foot. Most soldiers with trench foot could not return to combat. Many were crippled for life. In total, over 71,000 American soldiers got cold injuries in Europe during 1944–1945. In comparison, the British and Canadian armies combined reported only 206 cases.

On December 16, the Germans launched the Ardennes offensive. Fighting was very heavy. Hospitals near Liege quickly filled up. Hospital trains ran between Liege and Paris. Hospitals in Paris also filled up. Patients were moved to hospitals further back in Normandy and Brittany. Evacuation to the UK was difficult due to bad weather. In total, 85,000 patients were moved to the UK by sea in December, January, and February. Starting in February, planes began flying 2,000 patients a month across the Atlantic to the U.S.

Ammunition shortages

Why there wasn't enough ammo

It's hard to guess how much ammunition will be used. It depends on how battles go. Also, different battles need different types of ammunition. Ammunition shortages happened early in the campaign. This led to more casualties, delayed operations, and made the war last longer. The main reasons for the shortage of artillery ammunition in Europe in 1944 and 1945 changed over time:

- From June to November: Not enough capacity to unload ammunition from ships at beaches and ports.

- From August to October: Supply lines were too long and couldn't move enough ammunition to the front.

- From November 1944 to April 1945: Not enough ammunition was being made in the United States.

American tactics relied heavily on lots of gunfire. So, the ammunition shortage greatly affected battles. Especially in October, when armies faced the Siegfried Line defenses, major attacks were impossible. The First Army's operations were limited. The Third Army had to stop the Battle of Metz because of ammo shortages. For example, the 105 mm howitzer was a main weapon. The 12th Army Group suggested using 65 rounds per gun per day. But in one week in October, the First Army fired only 30 rounds per gun per day. The Third Army fired just 1.1 rounds per gun per day.

In September, unloading more troops was the priority at Cherbourg. Bad weather also affected unloading at Normandy beaches. So, only two ammunition ships were unloaded in the first week of October. General Lee found 4,000 tons of ammunition in abandoned dumps in Normandy. He also had ships loaded in England to unload ammo at Le Havre. The amount of ammunition unloaded slowly increased in October. By November, the depots near the front lines had almost 10,000 tons of ammunition.

How they tried to fix it

The armies found ways to deal with the shortages, usually by rationing ammunition. The 12th Army Group also tried to limit ammo use. But this rationing system often made shortages worse. It encouraged armies to grab as much ammo as possible if they thought it would be scarce. This created shortages for others. The rationing system also didn't react quickly to battle situations. Units facing a German counter-attack might not know how much ammo they'd have in a few days. Rationing also encouraged wasteful shooting to use up the allowance or faking reports to hide secret reserves.

On October 11, 1944, the 12th Army Group started a "credit system." Once enough ammo was stored in depots, armies were given a monthly allowance. This system helped the 12th Army Group know how much ammo was available. It stopped armies from ordering too much. Since ammo was given to a specific army, it encouraged them to save it during quiet times.

The armies didn't love the credit system at first. They still had rationing, so they couldn't always use the ammo they had. Also, they weren't sure about future deliveries. The 12th Army Group fixed this by ending rationing on November 5. They also gave 30-day forecasts for ammo, updated every ten days. The credit system didn't guarantee enough ammo, but it helped armies use what they had more wisely.

Sometimes, shortages could be helped by using non-standard ammunition. This wasn't ideal, as it reduced range and accuracy. Units also switched weapons. They used tanks, tank destroyers, and anti-aircraft guns if their ammo was more plentiful than artillery shells. Some battalions even used British 25-pounder guns, getting ammo from the British army.

Another source of ammo was captured German supplies. Dumps near Verdun and Soissons had French 155 mm howitzer ammunition, which worked with American 155 mm howitzers. The Third Army used only captured ammo for this type for a while. American tanks also used captured French 75 mm ammunition. German 8 cm mortar ammo worked with American 81 mm mortars. Some artillery battalions even used captured German weapons.

How ammo was organized

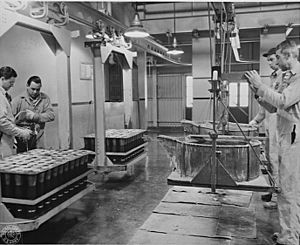

It was much easier to identify artillery ammunition than spare parts. Shells were usually painted olive drab. Different colored bands showed what was inside: yellow for high explosive, green for poison gas, red for tear gas, and yellow for smoke. The packaging showed the type and lot number. For best accuracy, ammunition from the same "lot" (batch made at the same time) should be fired together.

Ideally, a battalion would get ammo in large lots. But ammo lots often got mixed up between the factory and the battlefield. Small, mixed lots were common from the ports. Until November, the rush to unload ammo meant keeping lots together wasn't a priority. The First Army spent 25,000 man-hours sorting ammo by hand.

The New York Port of Embarkation (NYPE) tried to load ships with large, organized lots. Starting in November, all U.S. ammo came through just three ports. Here, special teams made sure the lots weren't broken up. Railroad cars were loaded with ammo from only one lot. All ammo from a ship went to a single depot. Armies then tried to get ammo from single lots from these depots.

Making more ammo

The United States wasn't as fully prepared for war as its enemies or allies. American production, while large, wasn't amazing considering its big population and industry. Munitions production peaked in late 1943. A review board then suggested cutting production. They thought too many supplies had been built up. The Ordnance Department disagreed, saying stocks weren't excessive. But their concerns were ignored.

To avoid making too much, war production in 1944 was limited. Many ammunition plants were closed or changed to make other goods. This especially affected larger artillery shells. In 1942, the U.S. Army thought heavy artillery wasn't mobile enough for Europe. They believed aircraft could replace it. So, heavy artillery and its ammo were given low priority and cut back.

This decision started to change in March 1944. Orders went out to increase production of large artillery ammo. For example, 155 mm howitzer ammo production was greatly increased. About $203 million (a huge amount of money back then) was spent on new factories to replace the ones that had just been closed.

By November 1944, shell shortages meant ammo was shipped directly from factories as soon as it was made. This saved about ten days of travel time.

In December, the Ordnance Department was told to increase production of light and medium artillery and mortar shells. Manpower was the biggest challenge. Many women were hired for jobs usually done by men. In some plants, half the workers were women. To get more skilled workers, some servicemen were temporarily released from duty to work in factories. The government also drafted men under 38 who had left essential factory jobs.

Tanks

Before D-Day, there were worries that tanks would be lost faster than expected. The War Department thought 7% of tanks would be lost each month. But actual losses were much higher. In August and September, tank losses were 25.3% and 16.5% respectively.

Tank reserves became very low. It was hard to keep tank battalions fully staffed. To share the tanks more fairly, the First Army reduced the number of tanks in its armored divisions. The Ninth Army did the same. By November, the 12th Army Group had fewer tanks than it needed. Two tank battalions had fewer than ten working tanks.

In December, the U.S. Army in Europe asked for 1,010 more tanks. At this time, the First Army was caught in the Ardennes fighting. It lost almost 400 tanks in December alone. They asked for a loan of 75 tanks meant for the Mediterranean. The commander there agreed to send 150 tanks. They also asked British General Montgomery, who agreed to send 351 Sherman tanks from British stocks. The British had a reserve of 1,900 Shermans from Lend-Lease. It was decided that all American tank production would go to U.S. forces until they built up a reserve of 2,000 tanks. But this wasn't expected until mid-1945.

Because of the tank shortage, plans to improve American armored forces were put on hold. The U.S. Army in Europe had to keep accepting older Shermans with 75 mm guns. They preferred the newer 76 mm gun version. But deliveries of the 76 mm version were behind schedule. This was due to changes needed for the heavier gun and retooling for a new 90 mm gun tank. It wasn't until January 1945 that the army felt they could ask for no more 75 mm gun Shermans.

Plans to upgrade 300 Shermans with the British 17-pounder gun were also stopped. There were no spare tanks to upgrade. Improved ammunition became available for the 76 mm gun, but very little arrived before March 1945. Shermans with the 105 mm howitzer were good for powerful explosive rounds. They were available, but their turrets couldn't turn fast enough. This was fixed, but these improved Shermans didn't arrive until April 1945. Meanwhile, the replacement for the Sherman, the M26 Pershing, started arriving in Europe in January 1945.

Food supplies

After the chase to the German border, food supplies were at their lowest on September 9. The First Army had only one and a half days of food. The Third Army had less than one day's worth. This was mainly because transportation problems meant deliveries didn't meet needs. For example, the First Army got 100,000 fewer rations than its strength on September 11. At the same time, the number of prisoners of war needing food jumped from 150,000 to 1,500,000. Captured German food helped. The Third Army seized 1,300 tons of frozen beef and 250 tons of canned meat. The First Army captured 265 tons of fresh beef.

Captured food also helped with boring diets. During the fast chase, transportation issues meant soldiers often ate only combat rations (C, K, and 10-in-1 rations). These made up 48% of food eaten, instead of the planned 18%. For a while, it looked like they would run out of combat rations. So, an order was given that combat units would get more B rations (standard garrison food without perishable parts).

Keeping the A and B rations "balanced" was hard. This meant having the right amounts of all food items so cooks could follow menus. Even though ships came with balanced rations, items could get mixed up or stolen. By September, there were 63 million pounds of unbalanced supplies. Since armies had almost no reserves, they ate whatever they got.

Food stock levels eventually got better. By the start of the November offensive, armies had several days' worth of supplies. The supply depot system became fully active in late November. During the German Ardennes offensive, the First Army got food from depots near Liege. Its forward depots were quickly emptied. The temporary stop in deliveries caused food to pile up at a depot in Cherbourg. The depot commander arranged for streets to be blocked off for open storage. This way, food from an entire ship could be kept together and stay balanced.

Even though combat rations provided enough nutrition, this was only true if all parts were eaten. To keep soldiers healthy, fresh produce was needed for those who had eaten only combat rations for over a month. Before D-Day, the British government set aside cold storage facilities for American needs. The first ships with perishable foods arrived from the U.S. They were unloaded in the UK and transferred to smaller refrigerated ships for the trip to France.

The U.S. Army in Europe had a fixed number of refrigerated ships. Monthly shipments depended on how fast these ships could unload and return. This was often slow. Littlejohn asked to cut shipments in October and November. He suggested shipping processed meats like bologna in regular storage. This saved refrigerated space and allowed for longer ship turnarounds. This worked well, and these meats arrived with little spoilage, as did fresh eggs.

Slow ship turnarounds were due to several reasons. Getting perishable goods delivered was complex. Unloading was often done by DUKWs because dock space was limited. Trains of refrigerated cars had to be ready. These cars needed to be cleaned, cooled, and inspected. A full train was best, as a few cars attached to other trains might be delayed. The slow return of refrigerated cars made it harder to assemble the next train, which slowed ship unloading.

The number of meat meals in the Communications Zone was cut from twelve to seven per week in October. This was to allow turkey for Thanksgiving. Poultry usually wasn't on the military menu because it took up more refrigeration space than beef or pork. But the promise of a turkey dinner had been made. It was felt that not providing it would hurt morale. In November, a ship arrived with 1,604 tons of turkey, which was distributed by refrigerated vans.

Fuel supplies

In September, both the armies and the Communications Zone faced a fuel shortage. By the third week of September, the Third Army had less than half a day's supply. The First Army had none. Even the Communications Zone had only a day and a half's worth in early October. By this time, the need for MT80 gasoline (80 octane fuel for vehicles) had risen greatly.

Part of the problem was how much fuel was being used. It reached a record high in September. It dropped in October and November. The Chief Petroleum Officer suggested a lower daily usage rate for future planning. Also, MT80 gasoline made up 90% of fuel used, not the expected 79%. So, the U.S. Army in Europe asked for 85% of shipments to be MT80.

It was unclear if this much fuel could be handled. In September, there were only two places on the continent where large amounts of petroleum could be received: Cherbourg and Port-en-Bessin in Normandy. Port-en-Bessin used floating pipelines that were often damaged by rough weather. Cherbourg also had limits, with only one tanker dock that was exposed to bad weather. Storage facilities at Cherbourg were thought to be enough but quickly proved too small. A pipeline was built to connect Cherbourg to other storage tanks.

The main pipeline system started at Cherbourg, but its construction was far behind the advancing armies. Progress was slow. The first pipeline didn't reach Coubert until early October. The other two didn't reach it until December. Coubert remained the eastern end of the pipeline system until January 1945. The pipeline systems had 950 miles of pipelines and large storage capacity. In September, responsibility for pipelines was given to the Military Pipeline Service.

From October, U.S. forces could get fuel from the British terminal at Ostend. Work also began to develop capacity at the Seine ports. At Le Havre, the petroleum facilities were mostly intact. Tankers could unload into barges or coastal tankers that could take fuel upriver. The first bulk fuel was unloaded at Le Havre on October 31.

Antwerp promised greater capacity. Its storage facilities could hold a lot of fuel. The first tanker docked at Antwerp on December 3. Plans were made to lay pipelines for MT80 gasoline and aviation fuel. Work began on December 8 and reached Maastricht by the end of January 1945.

Even though gasoline arrived in large amounts in tankers, most was given out in 5-gallon jerricans. There was a serious shortage of these due to wasteful practices in Normandy. By the end of November, a million discarded jerricans were found, but 500,000 were still missing. It was planned that the main supply group would pour fuel from large tanks into jerricans. But because pipeline construction was slow, armies received fuel in large amounts by train and truck directly from Cherbourg or the pipeline ends.

Armies started pouring their own fuel into jerricans. But this wasn't always successful. Proper equipment wasn't always available. Fuel deliveries were irregular. In November, large depots were set up near Liege and Verdun. Moving jerricans to and from Cherbourg was stopped. All fuel movement forward was then done in bulk by pipelines or rail. With Antwerp open, fuel for the First and Ninth Armies was landed there or at Ostend. It was then transported by tanker cars to Liege, where it was put into jerricans. By mid-December, armies had several days' supply of fuel.

During the German Ardennes offensive, the First Army's fuel depots at Spa and Stavelot were directly in the path of the German advance. The First Army Quartermaster ordered all fuel deliveries to be stopped. He heard that the Germans were relying on captured fuel. So, he ordered the depots to be emptied. Over the next three days, almost all the fuel was moved. The small amount left was burned to create a roadblock. The Germans did capture some fuel, and some was burned by American troops to prevent capture. But a nearby dump with 2 million gallons was emptied safely. By the end of December, the First Army's fuel stocks had dropped significantly.

Some 4,000 tons of supplies were moved from the depot at Eupen and the food depot at Welkenraedt. Attempts were made to keep ammunition supply points open as long as possible. The main ordnance depot was emptied, as were hospitals and engineer stores. But the map depot at Stevelot was lost. Large amounts of Bailey bridge equipment were too big to move. So, key parts were removed to make them unusable. At ammunition dumps, the highly secret proximity fuzes were prioritized for destruction if needed. Fuel depots near Liege were attacked by V-1 flying bombs. A V-1 attack on December 17 caused fires and the loss of 400,000 gallons of fuel. German jet bombers attacked Liege on December 24. Shipments to Liege were stopped. Once the fighting stabilized, the supply situation returned to normal in February 1945.

Coal supplies

Coal was needed for many military uses. It powered coal-burning trains, heated hospitals and barracks, cooked food, and provided hot water. Unlike other supplies, all coal came from the UK or was bought in Europe. For the invasion, 14,000 tons of sacked coal and 855 tons of bulk coal were set aside for the first six weeks. After that, only bulk coal would be supplied. The first coal arrived in July, three weeks late. Demand was higher than expected because coal was needed for public utilities in Cherbourg and Paris. The fast advance, the early liberation of Paris, and cold weather in September greatly increased the need for coal. But not enough coal arrived. Storms in early September delayed shipping from the UK. Cherbourg couldn't handle the planned amount due to a lack of railway cars. Other ports also had problems.

It was thought that the Germans would destroy coal mines, like they did in World War I. But the coalfields were captured before this could happen. A survey in September found 1 million tons of coal above ground. But only about 100,000 tons were suitable for trains or gas plants. Eisenhower ordered negotiations with France, Belgium, and the Netherlands for coal supplies. In November, the British agreed to ship another 25,000 tons of coal from the UK.

Stoves and water heaters at the front lines used liquid fuel. So, the main user of coal was the Communications Zone. Still, the armies and air force needed 82,000 tons of coal per month in winter. Deliveries were far short of this. The Third Army was supposed to get 18,000 tons per month but received only 8,297 tons in December. Where possible, wood was used instead of coal. The French provided some cut timber, but it wasn't enough. A program to get and cut more wood was started. But in January 1945, firewood production was only 36,000 cords, far less than the 1 million cords needed. This did help with the shortage of wooden supports needed in coal mines.

What was the result?

The decision to keep chasing the German army beyond the Seine River pushed the American supply system to its limits. Until the port of Antwerp opened in November 1944, no stable supply structure could be set up. Priority was given to the immediate needs of fighting units, first fuel, then ammunition. This sometimes meant other important things, like winter clothing and spare parts, were neglected.

The supply system struggled, which negatively affected battles. But it didn't completely break down. People at all levels found creative ways to work around the supply problems until transportation issues were fixed. The U.S. Army showed it could learn from its experiences and adapt to new situations. After the war, a board concluded that many problems in October and November could have been predicted. Time was lost as higher-ups tried to find solutions. By 1945, the supply difficulties were overcome. Even though supply losses during the fighting in the Ardennes were severe, they were quickly replaced.