Anglo-German Naval Agreement facts for kids

| Notes between His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and the German Government regarding the Limitation of Naval Armaments | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Naval limitation agreement |

| Signed | 18 June 1935 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Condition | Ratification by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the German Reichstag. |

| Parties | |

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) was a deal made on June 18, 1935. It was between the United Kingdom and Nazi Germany. This agreement set rules for how big Germany's navy, called the Kriegsmarine, could be compared to the British Royal Navy.

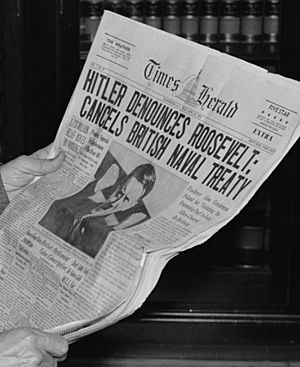

The agreement said that Germany's navy could only be 35% of the size of the Royal Navy. This rule was meant to last forever. It was officially recorded on July 12, 1935. However, Adolf Hitler ended the agreement on April 28, 1939.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement was an effort by both countries to get along better. But it didn't work out because they had different ideas about it. Germany saw it as a first step towards becoming allies with Britain against France and the Soviet Union. Britain, however, hoped it would be the start of many agreements to limit Germany's growing power. The agreement was always controversial. This was because the 35:100 size rule allowed Germany to build a navy bigger than what the Treaty of Versailles had allowed. Also, Britain made the deal without asking France or Italy first.

Contents

Why Was the Agreement Made?

Rules After World War I

After World War I, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles put strict limits on Germany's military. Germany was not allowed to have submarines or naval aircraft. It could only have a small number of old battleships and other ships. For example, Germany was allowed only six armored ships, six light cruisers, twelve destroyers, and twelve torpedo boats.

Over the years, many Germans felt these rules were unfair. They wanted Germany to be allowed to have a military like other European countries. In Britain, some people also felt the Versailles Treaty was too harsh. They thought it made sense to change the treaty to keep peace in Europe. A British official note from 1935 said their policy was to remove parts of the peace treaty that were "unstable and indefensible."

Britain's Concerns About Germany

When Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, Britain was worried. They weren't sure what Hitler's long-term plans were. Sir Maurice Hankey, a British defense official, visited Germany in 1933. He wondered if Hitler was still planning to attack other countries, or if he had become more responsible. This uncertainty about Hitler's plans shaped much of Britain's policy towards Germany until 1939.

The British Royal Navy had made big cuts to its size after the Washington Naval Conference (1921–1922) and the London Naval Conference 1930. These cuts, along with the Great Depression, hurt Britain's shipbuilding industry. This made it hard for Britain to build new ships later. So, the British Navy leaders, like Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield, thought it was better to make treaties. These treaties would limit the size and types of ships that other countries could build.

Admiral Chatfield especially wanted Germany to stop building its "pocket battleships" (called Panzerschiffe). These ships were a mix of battleships and cruisers, which he saw as dangerous. To encourage Germany to stop building them, Britain said in 1932 and 1933 that Germany had a "moral right" to have some of the Versailles Treaty rules relaxed.

World Disarmament Conference and German Demands

In February 1932, the World Disarmament Conference started in Geneva. A big debate was Germany's demand for Gleichberechtigung (equal rights in armaments). France, however, wanted sécurité (security), meaning they wanted to keep the Versailles rules. Britain tried to find a middle ground. They supported Germany's right to rearm a bit, but not so much that it would threaten France. Both France and Germany rejected Britain's ideas.

In September 1932, Germany left the conference. They said they couldn't get equal rights. Britain was worried that if Germany didn't get a foreign policy win, Hitler might gain more power. So, Britain pressured France, and in December 1932, other countries agreed to let Germany have "theoretical equality of rights." Germany then returned to the conference. This meant that before Hitler became chancellor, it was already accepted that Germany could rearm beyond Versailles limits. The exact amount of rearmament was still to be discussed.

When Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, Germany already had a strong position in the disarmament talks. Germany's plan was to offer small rearmament limits, expecting France to reject them. This would allow Germany to rearm as much as it wanted. France's strong opposition played into Germany's hands. In October 1933, Germany left the conference again. They said either everyone disarms to Versailles levels, or Germany reams beyond them.

Britain wrongly blamed France for Germany leaving the talks. Britain then felt they shouldn't miss any more chances for arms talks with Germany. Germany, however, kept making proposals that sounded good to Britain but were unacceptable to France.

Meanwhile, Admiral Erich Raeder, head of the German Navy, convinced Hitler to order two more "pocket battleships." By 1933, Raeder wanted a large German fleet by 1948. Hitler, from April 1933, wanted the German Navy to be 33.3% of the Royal Navy's size.

In November 1934, Germany officially told Britain they wanted a treaty. This treaty would allow the German Navy to grow to 35% of the Royal Navy's size. Admiral Chatfield advised that it would be best to make a naval treaty with Germany to control its future growth. The British Navy leaders thought 35:100 was the highest ratio they could accept for any European power. They believed Germany couldn't reach that size before 1942.

A British study in December 1934 suggested that a German navy focused on attacking merchant ships (a Kreuzerkrieg or "cruiser war" fleet) would be most dangerous. A "balanced fleet" (like Britain's, with battleships, cruisers, etc.) would be easier to defeat.

Secret U-boat Building

Even before Hitler, German governments had secretly broken the Versailles Treaty's rules. But after 1933, the Nazi government became more open about it. In 1933, Germany started building its first U-boats (submarines) since World War I. By April 1935, they launched their first ones. On April 25, 1935, Germany officially told Britain that they had laid down twelve 250-ton U-boats.

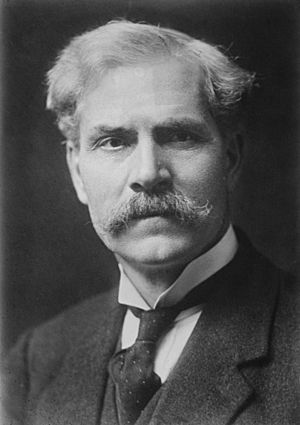

On April 29, 1935, British Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon told the British Parliament that Germany was building U-boats. On May 2, 1935, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced that his government planned to make a naval agreement with Germany.

Britain was in a difficult position to complain. They had supported Germany's "theoretical equality" at the disarmament conference. Germany argued they were just using rights that Britain had been ready to give them. A British official note in March 1934 said that the naval part of the Versailles Treaty was "dead." They felt it was better to make a new agreement while Hitler was willing to negotiate.

In December 1934, a secret British Cabinet meeting discussed German rearmament. They decided that since they weren't going to go to war to stop German rearmament, they should try diplomacy. This meant allowing Germany to rearm in exchange for Germany rejoining the League of Nations and the disarmament conference. In January 1935, Sir John Simon wrote that the choice was between Germany rearming without any rules, or Germany getting its rights recognized and helping with European stability. In February 1935, British and French leaders met in London. They proposed talks with Germany about limiting weapons and making security agreements.

The Talks Begin

In early March 1935, talks between Hitler and Sir John Simon were planned in Berlin. But Hitler postponed them, claiming he had a "cold." This happened after Britain released a report saying Germany was breaking the Versailles Treaty. During this delay, Germany formally rejected all parts of the Versailles Treaty that limited its land and air forces. Britain was very worried about German bombing attacks on London. So, they really wanted an air pact to ban bombing. A naval agreement was seen as a good first step towards that.

On March 26, 1935, Hitler told Simon and Anthony Eden that he would reject the naval disarmament part of Versailles. But he was willing to discuss a treaty to control German naval rearmament. On May 21, 1935, Hitler gave a speech in Berlin. He formally offered a treaty where the German Navy would always be 35% of the Royal Navy. Hitler said Germany had no intention of having a naval race with Britain like before 1914. He said Germany understood Britain's need for naval dominance to protect its empire. In return, Hitler expected Britain to accept Germany's power in Europe.

On May 22, 1935, the British Cabinet decided to accept Hitler's offer quickly. Sir Eric Phipps, the British ambassador in Berlin, advised London not to miss this chance for a naval agreement.

Hitler chose Joachim von Ribbentrop to lead the German team for the naval treaty talks. Ribbentrop arrived in London on June 2, 1935. The talks started on June 4. Ribbentrop was very eager to succeed. He immediately told the British that they had to accept the 35:100 ratio as "fixed and unalterable" by the weekend. Otherwise, the German team would leave, and Germany would build its navy to any size it wanted. Sir John Simon was angry and walked out of the talks.

However, on June 5, the British team changed its mind. They reported to the Cabinet that it was in Britain's best interest to accept Hitler's offer while it was still available. They feared that if they refused, Germany would build its navy even bigger than 35%. Also, on that day, the Germans agreed that the 35:100 ratio would apply to the total weight of ships in different categories. The British Cabinet voted to accept the ratio that afternoon.

For the next two weeks, talks continued on technical details. Ribbentrop was so desperate for success that he agreed to almost all British demands. On June 18, 1935, the agreement was signed in London by Ribbentrop and the new British Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare. Hitler called June 18, 1935, "the happiest day of his life." He truly believed it meant the start of an alliance between Britain and Germany.

How France Reacted

The Naval Agreement was signed without Britain talking to France or Italy first. France was very angry. They saw it as a betrayal and another way Britain was giving in to Hitler. France felt this deal further weakened the peace treaty and increased Germany's military power. France argued that Britain had no legal right to let Germany ignore the naval rules of the Versailles Treaty.

To make things worse for France, the agreement was signed on the 120th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. This was the battle where British and Prussian troops defeated the French under Napoleon.

What Was the Impact?

The agreement didn't have a huge impact because building warships takes a long time, and the agreement didn't last very long. Experts thought Germany couldn't reach the 35% limit before 1942. In reality, Germany had problems like not enough shipbuilding space, design issues, a lack of skilled workers, and not enough foreign money to buy raw materials. The German Navy (renamed Kriegsmarine in 1935) was third in line for resources, after the army and air force. So, the Kriegsmarine was still far from the 35% limit when Hitler ended the agreement in 1939.

The agreement forced Germany to build a "balanced fleet" that looked like the British Royal Navy. This was good for Britain. The Royal Navy believed a balanced German fleet would be easier to defeat in a war than a fleet designed to attack merchant ships. Also, the agreement stopped Germany from building more "pocket battleships," which the British didn't like.

By 1937, Hitler started giving more money and materials to the Kriegsmarine. This showed he was starting to think Britain would be an enemy, not an ally. In December 1937, Hitler ordered the building of six large battleships. He told British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax in November 1937 that the naval agreement was the only good thing left in Anglo-German relations.

By 1938, Germany used the agreement mainly to pressure Britain. They threatened to end it if Britain didn't accept Germany's control over Europe. Hermann Göring told the British ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, that the agreement was a mistake and Germany would build up to 100% of Britain's navy.

Britain responded that Göring's threat was "clearly bluff." They said Germany couldn't reach 100% because Britain would also keep building ships. Britain also warned that if Germany ended the agreement, it would be hard to have any general understanding between the two countries.

Hitler believed that by offering to limit his navy, Britain would let him have a "free hand" in Eastern Europe. But British politicians knew that Britain would always oppose any powerful country dominating Europe, especially if it threatened nearby countries like the Netherlands and Belgium. Britain would not trade one type of security for another.

Munich Agreement and Ending the Deal

At the Munich Agreement conference in September 1938, Hitler told Neville Chamberlain that if Britain planned to interfere in a European war, the agreement would no longer be valid. This led Chamberlain to mention the agreement in the Anglo-German Declaration of September 30, 1938.

By the late 1930s, Hitler was disappointed with Britain. German foreign policy became more anti-British. A big sign of this change was Hitler's decision in January 1939 to give the Kriegsmarine top priority for money and materials. He launched Plan Z, a huge plan to build a massive German navy by 1944. This fleet was meant to crush the Royal Navy. Since this planned fleet was much larger than the 35:100 ratio allowed, it was clear Germany would end the agreement.

Over the winter of 1938–1939, Britain realized Germany no longer planned to follow the agreement. This strained relations. Reports in October 1938 that Germany might end the agreement led Lord Halifax to push for a tougher policy with Germany. When Germany said on December 9, 1938, that it intended to build up to 100% of the submarine limit and the heavy cruiser limit, Chamberlain warned against "ambition, if ambition leads to the desire for domination."

When talks began in Berlin on December 30, 1938, Germany was uncooperative. Britain concluded that Germany didn't want the talks to succeed.

On March 31, 1939, Britain promised to help Poland if it was attacked. Hitler was furious. In a speech on April 28, 1939, he officially ended the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. To justify this, Germany stopped sharing information about its shipbuilding. This forced Britain to either accept Germany's unilateral move or reject it, giving Germany an excuse to end the agreement.

At a Cabinet meeting on May 3, 1939, British officials discussed the situation. They believed Germany still couldn't exceed the 35% ratio before 1942 or 1943. Lord Chatfield said Hitler had convinced himself that Britain had given him a "free hand" in Eastern Europe in exchange for the naval agreement. Chamberlain said Britain had never given such an understanding.

In the end, Britain sent a diplomatic note strongly denying Germany's claim that Britain was trying to "encircle" Germany with hostile alliances. Germany's ending of the agreement and reports of its increased shipbuilding (due to Plan Z) in June 1939 helped convince the British government that Germany's policies were a threat to Britain.

See also

- Appeasement

- Stresa front

- Events preceding World War II in Europe

Images for kids

-

Kurt von Schleicher in uniform, 1932

-

U-534, Birkenhead Docks, Merseyside, England

-

Nevile Henderson leaves for Berlin, Croydon Airport, August 1939

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |