Nevile Henderson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

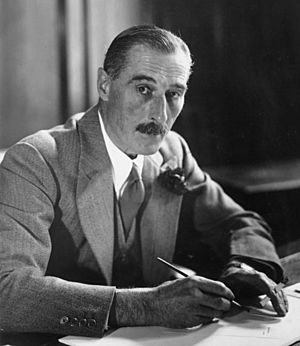

Sir Nevile Henderson

|

|

|---|---|

Ambassador Henderson in office, May 1937

|

|

| British Ambassador to Germany | |

| In office 28 May 1937 – 3 September 1939 |

|

| Monarch | George VI |

| Preceded by | Eric Phipps |

| Succeeded by | Sir Brian Robertson (1949) |

| British Ambassador to Argentina | |

| In office 1935–1937 |

|

| Monarch | George V (1935–36) Edward VIII (1936) George VI (1936–37) |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Henry Chilton |

| Succeeded by | Esmond Ovey |

| British Minister to Yugoslavia | |

| In office 21 November 1929 – 1935 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Sir Howard William Kennard |

| Succeeded by | Sir Ronald Ian Campbell (1939) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 April 1882 Sedgwick, Sussex, England |

| Died | 30 December 1942 (aged 60) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Education | Eton College |

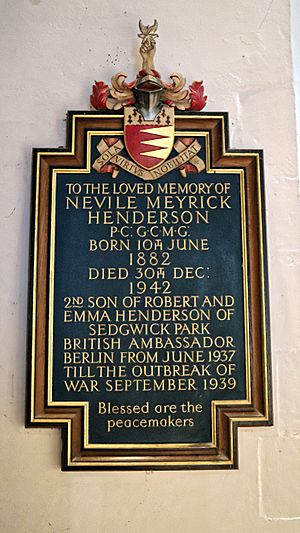

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat. He is best known for being the ambassador from the United Kingdom to Germany from 1937 to 1939. This was a very important time, just before the start of World War II.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Nevile Henderson was born at Sedgwick Park in Sussex, England. He was the third child of Robert Henderson and Emma Caroline Hargreaves. Nevile loved the countryside of Sussex, especially his home at Sedgwick. He felt a deep connection to it throughout his life. His mother, Emma, was a strong person who managed their family estate well after his father died in 1895.

He went to Eton College, a famous school in England. In 1905, he joined the Diplomatic Service. This meant he would work for the British government in other countries. Henderson enjoyed sports, especially hunting. He was also known for his elegant style. He always wore expensive suits and a red carnation flower. People thought he was one of the best-dressed men in the Foreign Office.

Ambassador to Turkey

In the early 1920s, Henderson worked at the British embassy in Turkey. This was a new country at the time. He helped manage the often difficult relationship between Britain and Turkey. Henderson played a big part in talks about the Mosul region in Iraq. Turkey's leader, Mustafa Kemal, claimed this area. Henderson strongly supported Britain's claim to Mosul. He also understood that Britain could not fight over every issue.

Ambassador to France and Yugoslavia

From 1928 to 1929, Henderson was an envoy in France. Then, from 1929 to 1935, he served as the British Minister to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He became good friends with King Alexander I of Yugoslavia. They both loved hunting and guns. In 1929, King Alexander had taken control of the government. He ended democracy and became a dictator. Henderson admired King Alexander greatly. His reports from Yugoslavia showed his strong support for the country. This friendship helped Britain's influence in Yugoslavia grow. It also brought Henderson to the attention of the Foreign Office.

After King Alexander was killed in 1934, Henderson felt very sad. He wrote that he felt more emotion than at any other funeral except his mother's. Henderson also worked closely with Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, who became regent for Alexander's young son, Peter II of Yugoslavia.

Ambassador to Argentina

In 1935, Henderson moved to become the British ambassador to Argentina.

Ambassador to Germany

On 28 May 1937, Henderson was appointed ambassador to Berlin, Germany. This was considered a very important diplomatic job. Henderson felt he had a special mission to help keep world peace. He read Adolf Hitler's book, Mein Kampf, to understand Hitler's ideas. Henderson wanted to see the good and bad sides of the Nazi government. He aimed to explain their goals to the British government fairly.

Henderson believed in a policy called appeasement. This meant trying to avoid war by giving in to some of Germany's demands. Like many British leaders, he thought the Treaty of Versailles had been too harsh on Germany after World War I. He believed that if Germany's concerns were addressed, another war could be prevented.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Henderson often disagreed with Sir Robert Vansittart, a senior official in the Foreign Office. Vansittart felt Henderson was getting too close to Nazi leaders. Henderson became particularly friendly with Hermann Göring, a powerful Nazi official. Göring and Henderson shared a love for hunting. They often went on hunting trips together to discuss relations between Britain and Germany. Henderson saw Göring as a "moderate" voice within the Nazi government. He believed that working with these "moderates" could prevent war.

Hitler called Henderson "the man with the carnation" because of the flower he always wore. However, Hitler actually disliked Henderson. Henderson's relationship with Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop was very difficult. Henderson thought Ribbentrop was full of himself. Henderson believed the Nazi government had different groups. He thought Göring led the "moderates," who wanted reasonable changes. He saw Ribbentrop, Josef Goebbels, and Heinrich Himmler as the "extremists." Henderson thought Britain should help the "moderates" by allowing Germany to regain some lost territories. These included the Free City of Danzig, parts of Poland, and former colonies. Henderson thought these demands were fair. However, he was wrong about Hitler. Hitler was the most extreme, and he would not be satisfied with small changes.

Henderson attended the 1937 Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg. He did this without asking the Foreign Office first. Vansittart was very angry. He worried that Henderson's attendance would make it seem like Britain approved of the Nazi system. Henderson believed it was important to be polite to Hitler. He thought ignoring Nazism would not make it go away. The Nazis saw his attendance as a sign of official approval.

Henderson spoke with Hitler at the rally. He thought Hitler seemed to want "reasonableness" in foreign affairs. Henderson believed Hitler's main goal was to get back Germany's former colonies in Africa. Some historians believe Hitler used these demands to pressure Britain. He wanted Britain to let Germany have a "free hand" in Eastern Europe.

The Sudetenland Issue

In 1938, a crisis grew over the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. This area had many German-speaking people. Henderson believed that the Sudeten Germans should have more rights. He thought Czechoslovakia should become a "Federal State" to solve its problems with different ethnic groups. Henderson worked with other diplomats to try and prevent a war. They wanted the Sudetenland to be given to Germany peacefully.

As the crisis got worse, Henderson became convinced that Britain should not fight a major war over the Sudetenland. He felt it was unfair that the Treaty of Versailles had given the Sudetenland to Czechoslovakia in the first place. Henderson was one of the few people who knew about Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's plan to fly to Germany. Chamberlain wanted to meet Hitler in person to find out what he truly wanted.

After Hitler gave a speech in September 1938 demanding the Sudetenland, Henderson reported that Hitler might have gone "insane." However, he still admired Hitler's "sublime faith" and called him a "constructive genius." Henderson believed Hitler did not want a full war. He thought Hitler only wanted fair treatment for Germans in Austria and the Sudetenland.

Henderson was the ambassador during the 1938 Munich Agreement. He advised Chamberlain to agree to it. This agreement gave the Sudetenland to Germany. Shortly after, Henderson returned to London for medical treatment. He was already ill with cancer, which would later cause his death.

Changes in Policy

When Henderson was away for treatment, another diplomat, Sir George Ogilvie-Forbes, took over the embassy in Berlin. Ogilvie-Forbes sent different reports to London. He believed Hitler wanted Germany to become a "world power." He also paid more attention to the suffering of German Jews under the Nazis. Ogilvie-Forbes even predicted the "extermination" of Jews in Germany.

When Henderson returned to Berlin in February 1939, he was upset by Ogilvie-Forbes's reports. He told his staff that all reports to London must match his own views. Henderson continued to believe that Hitler did not plan any new attacks. He also criticized British newspapers for their negative stories about Nazi Germany. He even suggested that the government should control the press. Henderson still praised Hitler and blamed Czechoslovakia's leader for the Munich crisis.

However, on 15 March 1939, German troops occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia. This went against the Munich Agreement. Chamberlain realized Hitler had betrayed their trust. Britain decided to resist further German aggression. Henderson delivered a protest note to Germany. He admitted that Germany's takeover of the "Czech lands" could not be justified.

By late March 1939, some in the British government felt Henderson could no longer represent Britain well in Berlin. But they kept him there because they had no other suitable important job for him. Henderson still believed Hitler wanted good relations with Britain. But only if Britain stopped trying to "encircle" Germany. He also thought Germany's demand for the Free City of Danzig to return to Germany was fair.

Leading to War

During the Danzig Crisis, Henderson continued to argue that Germany was right to demand Danzig back. He felt that the Treaty of Versailles had been unfair to Germany. He wanted Britain to pressure Poland to make concessions. However, he also believed Britain needed to show Germany that it would defend Poland. So, he supported an alliance with the Soviet Union as a deterrent.

Just before World War II began, Henderson often clashed with Sir Alexander Cadogan, a top Foreign Office official. Henderson thought Britain should rearm secretly. He worried that public rearming would make Germany think Britain wanted war. Cadogan and the Foreign Office disagreed.

The signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union on 23 August 1939 made war very likely. Two days later, Britain signed a military alliance with Poland. On 30 August, Henderson had a very tense meeting with Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop gave Germany's "final offer" to Poland. He warned that if there was no reply by dawn, it would be rejected. Henderson realized this was just an excuse for Germany to start a war.

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September. On the morning of 3 September 1939, Henderson had to deliver Britain's final warning to Ribbentrop. It said that if Germany did not stop fighting Poland by 11 a.m., Britain would be at war with Germany. Germany did not respond. So, Chamberlain declared war at 11:15 a.m. Henderson and his staff were briefly held by the German secret police before returning to Britain on 7 September.

Later Life

After returning to London, Henderson asked for another ambassador job, but he was not given one. He wrote a book called Failure of a Mission: Berlin 1937–1939, which was published in 1940. In his book, he spoke highly of some Nazi officials, like Hermann Göring, but not Ribbentrop.

Death

Nevile Henderson died on 30 December 1942 from cancer. He was staying at the Dorchester Hotel in London. Knowing he had little time left, he wrote another book of memories called Water Under the Bridges. It was published after he died in 1945. In this book, he defended his work in Berlin and the policy of appeasement. He praised Chamberlain and argued that Britain was not strong enough to fight Hitler in 1938.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |