Germaine de Staël facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Germaine de Staël

|

|

|---|---|

"Madame de Staël" by Marie-Éléonore Godefroid (1813)

|

|

| Born |

Anne-Louise Germaine Necker

22 April 1766 |

| Died | 14 July 1817 (aged 51) Paris, France

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein

(m. 1786; died 1802)Albert Jean Michel de Rocca

(m. 1816) |

| School | Romanticism |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

| Signature | |

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (born Necker; 22 April 1766 – 14 July 1817), known as Madame de Staël, was an important French writer and thinker. She was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a banker and France's finance minister, and Suzanne Curchod, who hosted a famous social gathering called a salon.

Germaine de Staël was a calm and sensible voice during the French Revolution and the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. She was present at key events like the Estates General of 1789. She worked closely with Benjamin Constant, and they became a famous intellectual pair. She was one of the first to see that Napoleon was becoming a harsh ruler. Because of this, she lived in exile for many years.

While in exile, she became the center of the Coppet group, a network of thinkers across Europe. One person in 1814 said that three great powers were fighting Napoleon: England, Russia, and Madame de Staël. She was known for being witty and brilliant in conversation. Her books, which included novels and travel stories, focused on being an individual and having strong feelings. These ideas greatly influenced European thought. De Staël also helped spread the idea of Romanticism widely.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Germaine, also called Minette, was the only child of Suzanne Curchod and Jacques Necker. Her mother was a Swiss governess who was good at math and science. Her father was a well-known Swiss banker and statesman. He became the finance minister for King Louis XVI of France. Her mother hosted one of the most popular salons in Paris.

Madame Necker wanted her daughter to be educated based on the ideas of the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. She also wanted Germaine to have the strong intellectual training and discipline that her own father had taught her. On Fridays, Germaine often sat at her mother's feet in the salon. The guests enjoyed talking with the bright young child. By age 13, she had read works by Montesquieu, William Shakespeare, Rousseau, and Dante Alighieri.

In 1781, her father did something new. He made the country's budget public, which was unusual for a monarchy. This led to him being fired. In 1784, her family moved to Coppet Castle in Switzerland. They returned to the Paris area in 1785.

Her Marriage

When Germaine was 11, she joked that she wanted to marry Edward Gibbon, a guest at her mother's salon. She thought he was very interesting. At 17, she was courted by William Pitt the Younger and Jacques Antoine Hippolyte, Comte de Guibert. She found Guibert's conversations especially lively.

Since she didn't accept their offers, her parents became impatient. With help from a friend, a marriage was arranged with Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein. He was a Protestant and worked for the Swedish embassy in France. They married on 14 January 1786, when Germaine was 20 and her husband was 37. The marriage worked for both of them, even though they didn't have much affection for each other. Germaine continued to write plays. The Baron benefited greatly from the marriage, receiving money and being confirmed as ambassador for life.

Involvement in the Revolution

In 1788, de Staël published Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau. In this book, she showed her talent. She was excited by Rousseau's ideas about love and Montesquieu's ideas about politics.

In December 1788, her father convinced the king to double the number of representatives for the common people. This was to get support for raising taxes to pay for the American Revolution. This decision hurt her father's reputation. He was dismissed and exiled in July 1789. News of this led to calls for storming the Bastille. He was later reappointed but resigned in September 1790. Her parents then left for Switzerland.

As the Revolution grew, her status as an ambassador's wife protected her. Germaine held a salon at the Swedish embassy. Many moderate politicians and thinkers, like Talleyrand and Antoine Barnave, visited. She believed that Mirabeau was the only leader who could keep the Revolution on a path of constitutional reform. His death was a sign of great confusion.

After the French Constitution of 1791 was announced, she decided to step back from politics. However, she still played a role behind the scenes. She helped get Narbonne appointed as Minister of War. In August 1792, violence increased. De Staël helped Narbonne hide in the Swedish embassy. She also tried to help the royal family escape.

On 2 September 1792, the September massacres began. De Staël fled Paris dressed as an ambassadress. Her carriage was stopped, and she was taken to the Paris town hall, where Maximilien Robespierre was present. She was later escorted home and then helped to leave the city with a new passport.

Salons in Switzerland and Paris

After leaving Paris, de Staël moved to Rolle in Switzerland. She was supported by friends. In January 1793, she visited England for four months to be with Comte de Narbonne. She met important people like Horace Walpole. She was not impressed with the situation of women in English society. She valued individual freedom as much as political freedom.

In summer 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland. She published a defense of Marie Antoinette. She believed France should become a constitutional monarchy, like England. In September 1794, Benjamin Constant visited her.

In May 1795, de Staël moved back to Paris with Constant. She reopened her salon, where she had great political influence. However, she was ordered to leave Paris after being accused of political plotting. She was seen as a threat to stability. She corresponded with Francisco de Miranda. In 1796, she published Sur l'influence des passions, which caught the attention of German writers Schiller and Goethe.

In May 1797, she was back in Paris. She helped Talleyrand return from the United States and become Minister of Foreign Affairs. She became a close friend of Juliette Récamier. De Staël also wrote an important work on political theory, "Of present circumstances that can end the Revolution."

Conflict with Napoleon

On 6 December 1797, de Staël met Napoleon Bonaparte for the first time. She met him again in January 1798. She told him she disagreed with his plan to invade Switzerland, but he ignored her.

In January 1800, Napoleon appointed Benjamin Constant to a political body. Two years later, Napoleon forced Constant into exile, believing de Staël had written his speeches. In August 1802, Napoleon became first consul for life. This made de Staël oppose him for both personal and political reasons. She saw Napoleon as a tyrant. Napoleon, however, thought writers like Voltaire and Rousseau caused the French Revolution. He believed women should not be involved in politics. He said she "teaches people to think who had never thought before." It was clear they would never get along.

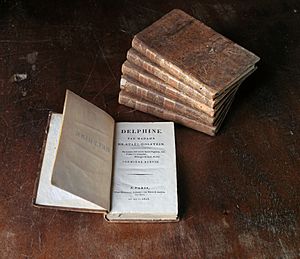

De Staël published a novel called Delphine in 1802. It was about a misunderstood woman in Paris facing conservative ideas. The book also touched on the French Revolution and the fate of those who fled France.

When Constant moved away in September 1803, de Staël visited him. She tried to assure Napoleon she would be careful. Her house became popular again, but Napoleon suspected a conspiracy. Her wide network of friends, including foreign diplomats and opponents, worried the government. On 13 October 1803, Napoleon exiled her without a trial.

Years of Exile

For ten years, de Staël was not allowed to come within 200 kilometers of Paris. She accused Napoleon of "persecuting a woman and her children." On 23 October, she left for Germany, hoping to gain support and return home soon.

German Travels

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped in Metz. In December, they arrived in Weimar, where she stayed for two and a half months. She met Goethe, who called her an "extraordinary woman." Schiller praised her intelligence. De Staël was always moving, talking, and asking questions. Constant left her in Leipzig and returned to Switzerland. De Staël traveled to Berlin, where she met August Wilhelm Schlegel. She hired him to teach her children. On 18 April, they all left Berlin after hearing of her father's death.

Mistress of Coppet Castle

On 19 May, de Staël arrived at Coppet Castle, now its wealthy owner. She spent the summer organizing her father's writings. In July, Constant wrote that she had an "inexplicable but real power." In December 1804, she traveled to Italy with her children and Schlegel. Her visit helped her understand the differences between northern and southern European societies.

De Staël returned to Coppet in June 1805. She spent almost a year writing her next book about Italy's culture and history. In Corinne, ou L'Italie (1807), she shared her impressions of Italy. The book combined romance with travel writing. It showed Italy's artworks still in place, not taken by Napoleon. The book reminded Napoleon of her, and he sent her back to Coppet. Her home became a center for European thought and a place where people discussed ideas against Napoleon. Many famous people, including Juliette Récamier and Chateaubriand, visited.

De Staël began working on her book about Germany. In it, she presented Germany as a model of ethics and art. She praised German literature and philosophy. Her conversations with Goethe and Schiller inspired her to write this important book.

Return to France and Second Exile

De Staël was given permission to re-enter France by pretending she wanted to move to the United States. She moved to Château de Chaumont in 1810. She wanted to publish De l'Allemagne in France. This book questioned French political structures, indirectly criticizing Napoleon. The police minister forbade her from publishing her "un-French" book. In October 1810, de Staël was exiled again and had to leave France within three days. August Wilhelm Schlegel was also ordered to leave. She found comfort in a younger officer named Albert de Rocca. They secretly got engaged in 1811 and publicly married in 1816.

Travels in Eastern Europe

De Staël's movements were watched by the French police. Her visitors were also persecuted. Friends like François-Emmanuel Guignard and Mme Récamier were exiled for visiting her. In May 1812, she left Coppet. She traveled through Bern, Innsbruck, and Salzburg to Vienna. There, she received passports to go to Russia.

During Napoleon's invasion of Russia, de Staël, her children, and Schlegel traveled through Galicia. They continued to Lemberg and then to Volhynia. Napoleon's army had already crossed the Niemen River. In Kyiv, she met the city's governor. She decided to go north instead of to Odessa. In Moscow, she was invited by the governor Fyodor Rostopchin. She left Moscow only a few weeks before Napoleon arrived.

Her party stayed in Saint Petersburg until September. The American ambassador there noted that her strong feelings against Napoleon came from both personal anger and her general political views. She complained that he wouldn't let her live in peace. She met Tsar Alexander I twice.

After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, she began writing "Ten Years' Exile," about her travels. She supported Jean Baptiste Bernadotte as the new ruler of France, hoping he would bring a constitutional monarchy. After eight months, she left for England.

In London, she received a warm welcome. She met Lord Byron, William Wilberforce, and Humphry Davy. Byron said she preached politics to everyone. In March 1814, she invited Wilberforce for dinner. She spent her remaining years fighting to end the slave trade. Her stay was saddened by the death of her son Albert, who died in a duel. In October, her book De l'Allemagne was published. It discussed nationalism and suggested new ideas about cultural boundaries. In May 1814, after Louis XVIII was crowned, she returned to Paris. Her salon again became a major attraction.

Later Life and Passing

When Napoleon returned to France in March 1815, de Staël fled to Coppet again. She never forgave Constant for supporting Napoleon's return. She managed to get back the large loan her father had made to the French state before the Revolution. In October, after the Battle of Waterloo, she went to Italy for her health and her husband de Rocca's health. In May, her daughter Albertine married Victor, 3rd duc de Broglie.

The family returned to Coppet in June. Lord Byron visited de Staël often. He thought she was Europe's greatest living writer. Byron supported Napoleon, but de Staël saw Napoleon as a harmful system of power. She believed Napoleon forced French culture on Europe, which she disliked.

Despite her worsening health, de Staël returned to Paris for the winter of 1816–17. She became friends with the Duke of Wellington. She used her influence to reduce the size of the army occupying France.

De Staël became paralyzed in February 1817 after a stroke. She passed away on 14 July 1817. Rocca died just over six months after her.

Her Children

De Staël had two daughters who died as babies. She had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827) and Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed that Louis, comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludwig August and Albert. Benjamin Constant is thought to be the father of Albertine. With Albert de Rocca, de Staël had one son, Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842).

After de Staël's death, Mathieu de Montmorency became the legal guardian of her children. He and August Schlegel were close friends with her until the end of her life.

Her Lasting Impact

Albertine Necker de Saussure, de Staël's cousin, wrote her biography in 1821. Auguste Comte included Madame de Staël in his "Calendar of Great Men." Her political ideas are known for strongly defending "liberal" values. These include equality, individual freedom, and limiting the power of the state through constitutional rules. She believed that politics was essential to her life. However, her views on women's role in politics changed. Sometimes she said women should only care for the home. Other times, she argued that denying women public roles was wrong.

Historians, including feminists, have recently looked at de Staël's contributions as a woman writer and thinker. She has been called an early supporter of feminism.

Her novels came before the works of Walter Scott and Lord Byron. They are very important in the development of modern Romanticism. They show a love for nature, arts, old things, and European history.

Her Writings

- Journal de Jeunesse, 1785

- Sophie ou les sentiments secrets, 1786

- Jane Gray, 1787

- Lettres sur le caractère et les écrits de J.-J. Rousseau, 1788

- Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine, 1793

- Réflexions sur la paix adressées à M. Pitt et aux Français, 1795

- De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations, 1796

- De la littérature dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales, 1799

- Delphine, 1802 – a novel about a woman's place in society.

- Vie privée de Mr. Necker, 1804

- Corinne, ou l'Italie, 1807 – a travel story and novel about female creativity.

- De l'Allemagne, 1813, translated as Germany 1813.

- Considérations sur les principaux événements de la révolution française, 1818 (published after her death)

- Dix Années d'Exil (Ten Years' Exile), 1818 (published after her death)

See also

In Spanish: Anne-Louise Germaine Necker para niños

In Spanish: Anne-Louise Germaine Necker para niños

- Liberalism

- Women in the French Revolution