Arab Agricultural Revolution facts for kids

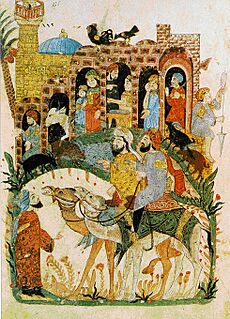

The Arab Agricultural Revolution describes a big change in farming across the Old World between the 8th and 13th centuries. This period is also known as the Islamic Golden Age. During this time, people in Islamic lands learned a lot about farming and gardening. They shared many useful plants, like olives and pomegranates, especially in medieval Spain, called al-Andalus.

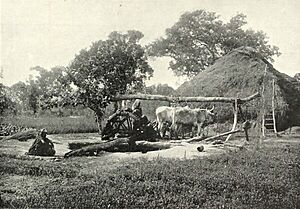

Archaeologists have found proof of better ways to raise animals and improved irrigation systems, like the saqiyah waterwheel. These changes made farming much more productive. This helped more people live in cities and led to new ways of organizing society. The idea of an "Arab Agricultural Revolution" was first suggested by historian Andrew Watson in 1974. Today, many historians agree that these changes were very important.

Contents

A Time of Big Changes in Farming

How Farming Grew in Islamic Lands

Smart Farming Ideas

The study of farming is called agronomy. The first Arabic book on agronomy to reach al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) was The Nabatean Agriculture from Iraq in the 10th century. Later, scholars in al-Andalus wrote their own books. For example, Al-Zahrawi from Cordoba wrote an abridged book around 1000 AD.

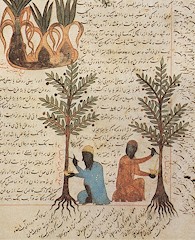

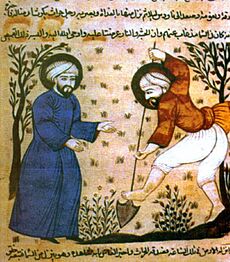

A famous agronomist named Ibn Bassal from Toledo lived in the 11th century. He traveled widely and learned a lot about farming. His book, Dīwān al-filāha (The Court of Agriculture), described 177 different plant species. He explained how to grow and care for many useful plants, including vegetables, herbs, spices, and trees.

Another important agronomist was Ibn al-'Awwam in the 12th century. His book, Kitāb al-Filāha (Treatise on Agriculture), gave detailed instructions. He wrote about how to plant olive trees, how to graft them (joining parts of two plants), how to treat their diseases, and how to harvest them. He also gave similar advice for crops like cotton.

These scholars described many farming and gardening techniques. They explained how to grow olives and date palms. They also wrote about crop rotation, which means planting different crops like flax and wheat in the same field over time. This helps keep the soil healthy. These books show that farming was both a traditional skill and a serious science. In al-Andalus, these guides helped farmers try new plants and methods. Even rulers, like the sultan in Seville, were interested in improving fruit production.

Raising Animals Better

Archaeological studies of animal bones show changes in animal farming. In southern Portugal, sheep grew larger during the Islamic period. This suggests that farmers were using selective breeding to improve their animals. When the area later became Christian, cattle increased in size instead. Historians believe these changes show better animal husbandry (the care and breeding of farm animals). The preference for sheep might be linked to the Islamic liking for mutton.

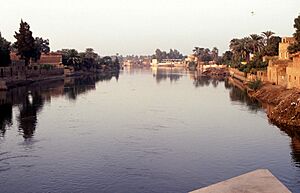

Watering the Land: Irrigation

During this period, farmers used more animal power, water power, and wind power to water their fields. Windpumps, which use wind to pump water, were used as early as the 9th century in places like Afghanistan and Iran.

In areas like the Fayyum in Egypt and al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), huge irrigation systems were built. These systems used canals to bring water to farms. Local communities often managed these water systems. In al-Andalus, the network of irrigation canals grew much larger. New villages, orchards, and sugar cane farms, all needing water, were also developed.

The sakia, an animal-powered waterwheel, likely came to Islamic Spain in the 8th century. Agronomists in Spain later improved it. From Spain, the sakia spread to other parts of Spain and Morocco. One observer in the 13th century claimed there were "5000" waterwheels along the Guadalquivir river in Islamic Spain. Even if this was an exaggeration, it shows how widespread irrigation was. These water systems also supplied cities. For example, the Roman aqueducts in Cordoba were repaired and expanded during the Islamic period.

Life in Islamic Spain

Medieval historians and geographers described Islamic Spain as a very lucky and rich place. They said it had good soil, many rivers and springs, and plenty of water channels. It was known for wheat, olive oil, wine, and many kinds of fruits. They mentioned beautiful gardens and orchards with all sorts of fruit trees, including white mulberry trees for silkworms.

One writer, Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Musa al-Razi, described al-Andalus as a fertile land "flowing copiously with plentiful rivers and fresh springs." It was famous for cultivated trees like olive and pomegranate. After the Reconquista (when Christians took back control), some farming was stopped, and land became pasture. However, some farmers tried to continue using Islamic farming methods. Historians today have found that archaeological evidence largely supports these old descriptions of a rich and fertile land.

Was it a "Revolution" or Just "New Ideas"?

The First Ideas of a Farming Revolution

In 1876, historian Antonia Garcia Maceira suggested that farming in Spain changed a lot under "the Arabs." She believed they brought new knowledge and improved crops, leading to an agricultural "revolution."

Later, in 1974, historian Andrew Watson expanded on this idea. He proposed that the trade networks created by Arab and Muslim traders helped spread many crops and farming techniques across the Old World. He listed 18 crops, like sorghum from Africa, citrus fruits from China, and rice, cotton, and sugar cane from India. Watson believed these new crops, along with better farming tools and irrigation, caused big changes. These changes affected the economy, where people lived, what food was grown, and even what people ate and wore.

Other historians agreed. Howard R. Turner wrote in 1997 that Islamic studies of soil and climate led to "remarkably advanced horticulture and agriculture." He noted that this knowledge, passed to Europe, improved farming and increased crop variety. In 2006, James E. McClellan III and Harold Dorn said that Islamic farmers helped create a "scientific civilization." They adapted new crops to the Mediterranean climate and used improved irrigation to grow more food. They also mentioned many books on farming and animals like horses and bees. They linked these farming improvements to population growth, city development, and new social structures.

By 2008, archaeozoologist Simon Davis confirmed that in Spain, Muslims introduced new irrigation and plants like sugar cane, rice, cotton, spinach, pomegranates, and citrus trees. He called Seville a "Mecca for agronomists." In 2011, Paulina B. Lewicka noted that in medieval Egypt, this farming revolution led to a "commercial revolution" and even a "culinary revolution," changing Egyptian food.

Some Historians Had Doubts

Not everyone agreed with Watson's idea right away. In 1984, historian Jeremy Johns questioned some of Watson's claims. He pointed out that some of the crops Watson listed, like banana and mango, were not very important in the Islamic region at that time. Johns also noted that the evidence for crop spread was not perfect.

Other historians, like Eliyahu Ashtor (1976) and Michele Campopiano (2012), looked at records from Iraq and Egypt. They suggested that agricultural production actually went down in some areas right after the Arab conquest. Campopiano thought this decline was due to different ruling groups fighting over land.

Spreading Ideas, Not Always New Ones

In 2009, historian Michael Decker argued that many important crops were already common centuries before the Islamic period. These included durum wheat, Asiatic rice, sorghum, and cotton. He suggested that their role in Islamic agriculture might have been exaggerated. Decker believed that Muslim farming methods were not completely new. Instead, they built upon the water management skills and plants inherited from the earlier Roman and Persian empires.

For example, cotton was grown by the Romans in Egypt. Decker said it remained a minor crop in the Islamic period, with flax being the main fiber, just like in Roman times. He also argued that ancient irrigation was already advanced. Archaeological findings in Spain showed that the Islamic irrigation system often developed from existing Roman networks, rather than replacing them entirely. Decker agreed that Muslims helped spread some crops to the west. However, he thought the introduction of new farming techniques was less widespread than Watson had suggested. Many farming tools, like watermills, waterwheels, and water pumps, were known and used in Greco-Roman agriculture long before the Muslim conquests.

New Ways of Organizing Farming

| The main trade of [Seville] is in [olive] oils which are exported to the east and the west by land and sea. These oils come from a district called al-Sharaf which extends for 40 milles and which is entirely planted with olives and figs. It reaches from Seville as far as Niébla, having a width of more than 12 milles. It comprises, it is said, eight thousand thriving villages, with a great number of baths and fine houses.—Muhammad al-Idrisi, 12th century |

Historian D. Fairchild Ruggles offered a different view. She disagreed with the idea that medieval Arab historians were wrong about a farming revolution. She argued that even if they didn't know much about farming before their time, they were right about big changes in Islamic Spain. She believed a whole new system of crop rotation, fertilizing, transplanting, grafting, and irrigation was quickly put in place. This was supported by new laws about land ownership and how land was rented.

So, for Ruggles, there was indeed an agricultural revolution in al-Andalus. But it was mainly about new ways of organizing society and farming, rather than just new techniques. She stated that this "dramatic economic, scientific, and social transformation" started in al-Andalus and spread across the Islamic Mediterranean by the 10th century.

Looking Back at the Debate

In 2014, Paolo Squatriti looked back at 40 years of research since Watson's theory. He noted that Watson's idea had been very useful to many historians and archaeologists. It helped them discuss how technology spreads, the history of Islamic civilization, and the start of global connections.

Squatriti mentioned that Watson, who studied economics, focused on the "diffusion and normalization" of plants. This meant plants became widely used, even if they were known before. Squatriti was surprised that recent studies using archaeobotany (the study of ancient plants) had not "decisively undermine[d]" Watson's main idea. This suggests that even with new evidence, the core idea of significant agricultural change during this period remains strong.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |