Arkansas Post facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Arkansas Post |

|

|---|---|

Partial reconstruction of the

Revolutionary War era fort |

|

| Nearest city | Gillett, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Area | 757.51 acres (306.55 ha) |

| Elevation | 174 ft (53 m) |

| Built | 1686 |

| Built for | Louis XIV of France |

| Original use | Trading post |

| Restored | February 27, 1929 |

| Restored by |

|

| Visitors | 25,032 (in 2023) |

| Governing body | U.S. National Park Service |

| Official name: Arkansas Post National Memorial | |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000198 |

| Designated | July 6, 1960 |

| Designated by | President Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Arkansas Post was the very first European settlement along the Mississippi River. It was also the first in what is now the state of Arkansas. In 1686, a French explorer named Henri de Tonti started it. He built it for King Louis XIV of France as a place to trade with the Quapaw people.

This spot was very important to the French, Spanish, and later the Americans. The U.S. got the land in 1803 with the Louisiana Purchase. Arkansas Post was even the capital of Arkansas from 1819 to 1821. Then, the government moved to Little Rock.

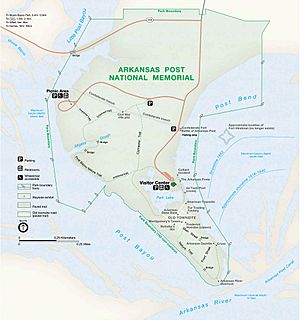

Over the years, Arkansas Post had many forts to protect its trade. These forts and towns were built in a few different places. Some of the old buildings have been lost because the river's edge has been washed away or flooded. Today, about 757 acres of the site are protected as the Arkansas Post National Memorial. It's a special place that remembers history.

Scientists have done three archeological digs at Arkansas Post since the 1950s. They say the most important historical items are found underground. These include remains from the 1700s and 1800s European-American towns. There are also older Quapaw villages. The Arkansas River has changed over time, and some old forts are now underwater.

Contents

Exploring the History of Arkansas Post

French Control: 1686 to 1763

The First Settlement Location

Henri de Tonti and other Frenchmen started Arkansas Post in the summer of 1686. It was a trading post near a Quapaw village called Osotouy. This spot was about 35 miles upriver from where the Arkansas River meets the Mississippi River. De Tonti received this land for his help in an expedition in 1682.

The French agreed to trade their goods for beaver furs from the local Quapaw people. This trade wasn't very profitable because the Quapaw didn't hunt many beavers. But having good relationships with the Quapaw and other local tribes, like the Caddo and Osage, was key to the post's survival.

The French settlers first called the post Aux Arcs. This meant "at the home of the Arkansas." The word Arkansea was an Algonquian name for the Quapaw people. The traders built a simple wooden house and a fence. This was the first European town on the entire Mississippi River. It was also the first permanent French settlement west of the Mississippi. Here, the French held the first Christian services in Arkansas.

The post became more important in 1699 when King Louis XIV of France put more money into French Louisiana. A company tried to bring German settlers to the area from 1717 to 1724. The idea was to grow crops for trade with Arkansas Post, New Orleans, and French Illinois. The French brought about 100 enslaved people and workers to help. But this plan failed when the company ran into money problems. Most of the enslaved people and workers were moved or sold. However, a few stayed near the post and became hunters, farmers, and traders.

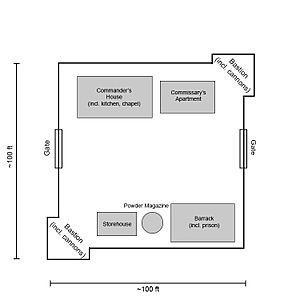

By 1720, the post was not as important to the French because it wasn't making much money. The population was small. In 1723, thirteen French soldiers guarded the post. In 1731, the post was made much bigger. New buildings included a place for soldiers, a gunpowder storage, a jail, and a house for the commander.

On May 10, 1749, during the Chickasaw Wars, the post had its first battle. Chief Payamataha of the Chickasaw attacked the farms and homes around the post. He killed and captured several settlers.

The site of this first post is thought to be near the Menard–Hodges site. This area is about 5 miles from the Arkansas Post Memorial. It is also a National Historic Landmark.

The Second Location: Red Bluff

After the Chickasaw attack, the commander moved the post upriver. This was further from Chickasaw land and closer to the Quapaw villages. The Quapaw were the main trading partners and possible allies. This new spot was about 45 miles from the river's mouth. It was called Écores Rouges (Red Bluff) and was on higher ground.

In 1752, the next commander rebuilt the main buildings. These included the soldiers' quarters, jail, and gunpowder storage. He also made the commander's house bigger to include a chapel and rooms for the priest. He added a storehouse, a hospital, a bakery, and a restroom. To protect these new buildings, he built a tall wooden fence called a stockade.

The Third Location

In 1756, the Seven Years' War started between France and England. The post was moved again to a spot 10 miles from the Mississippi River. This was to help it respond better to British and Chickasaw attacks. The first two posts were on the north side of the Arkansas River. This new one was on the south side. It had similar important buildings protected by a stockade.

Spanish Control: 1763 to 1802

After the British won the Seven Years' War, France gave its land west of the Mississippi to Spain. This was part of a deal. The post officially became Spanish in 1763, but Spain didn't take control until 1771.

At first, the Spanish kept the post at the third site. They built the first Fort Carlos there to defend it. Most of the people living at the post were still French. This made things tricky for Spain. In 1772, the Spanish commander was told to show that Spain was in charge. He was also told to give fewer parties and gifts to the Quapaw. This was because it cost too much. The Quapaw almost started a fight, but the commander eventually gave in and restored the gifts.

The Fourth Location: Back to Red Bluff

In 1777 and 1778, floods partly covered the post. The army captain asked the Spanish governor of Louisiana to move the post upriver. He worried about the yearly floods and being far from the Quapaw villages. In 1778, some American officers stopped here on their way to ask Spain to help the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War.

The governor allowed the post to move back to the second French site at Red Bluff. In 1779, the post was moved. People hoped it would flood less there. Fort Carlos III was built here in July 1781. It had several small buildings surrounded by a stockade. In the late 1700s, some Americans from the new United States settled at the post. They built a separate American village closer to the Quapaw villages. Many of these settlers were seeking safety from the American Revolutionary War.

The only battle of the Revolution fought in what is now Arkansas happened on April 17, 1783. A British captain led British fighters and Chickasaw allies in an attack on the Spanish at Arkansas Post. This was part of a small British effort against the Spanish during the war. The Spanish defended the fort with their soldiers, Quapaw allies, and settlers.

Fort Carlos III was slowly being washed away by the river. So, the Spanish moved the army base about half a mile from the river. In March 1791, they built Fort San Estevan. This fort included a commander's house, large soldiers' quarters, a storehouse, and a kitchen. All were surrounded by a stockade. After the Louisiana Purchase, it was renamed Fort Madison.

Brief French Ownership Again: 1802 to 1804

Spain gave Louisiana and Arkansas Post back to France in 1800. But no French officials came to run the post. Spanish soldiers stayed in charge until the United States bought the land.

United States Control: 1804 to Today

In 1804, Arkansas Post became part of the United States. This happened because of the Louisiana Purchase from France. At that time, the post had 30 houses on two streets. Most of the people living there were French.

American settlers mostly lived in separate villages north of the post. More Americans moved in after the purchase. Americans built new buildings alongside the French and Spanish ones. Fort Madison guarded the post until 1810. It was then abandoned because of erosion and floods.

In 1805, the U.S. government built a trading house at the north end of the post. It was a major stop for travelers heading west. Explorers like Stephen Harriman Long and Thomas Nuttall passed through. The government closed the trading house in 1810.

Arkansas Post was chosen as the capital of Arkansas County in 1813. In 1819, it became the first capital of the new Arkansas Territory. It was the center for business and government in Arkansas. The territory's first newspaper, the Arkansas Gazette, started here in 1819.

A tavern operated at the post from 1819 to 1821. This building also hosted the first Arkansas Territorial General Assembly in February 1820. While it was the capital, Arkansas Post grew a lot. Two new towns were built nearby.

Over time, more people settled further into the Arkansas River Valley. Little Rock became the main settlement. When the capital moved there in 1821, many businesses and government offices moved too. Arkansas Post lost much of its importance.

The town continued to be active as a river town through the 1840s. This was because more steamboats traveled on the rivers. A French businessman, Colonel Frederick Notrebe, became very important in the town's business. He owned a house, a store, a brick store, a warehouse, a machine to clean cotton, and a press. In the 1840s, the post grew with new buildings. One was for the Arkansas Post Branch of the State Bank of Arkansas. By the 1850s, the post was getting smaller, and its population dropped a lot.

A well and a cistern (water tank) were built at the post in the early 1800s. They are still at the memorial site today.

Civil War and Confederate Control: 1861 to 1863

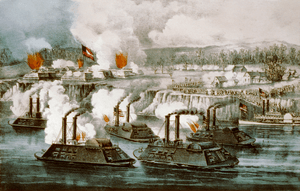

During the American Civil War, Arkansas Post was still an important military spot. In 1862, the Confederate States Army built a huge dirt fort called Fort Hindman. It was named after Confederate General Thomas C. Hindman. The fort was on a bluff 25 feet above the river. It had a one-mile view up and down the river. Its purpose was to stop Union forces from going upriver to Little Rock. It also aimed to disrupt Union movement on the Mississippi.

From January 9–11, 1863, Union forces attacked the fort from both land and water. They had warships covered in iron helping them. The Union forces had many more soldiers (33,000) than the Confederates (5,500). They won easily and captured the post. Most of the Confederate soldiers surrendered. During the battle, cannon attacks destroyed or badly damaged the fort and some town buildings. Arkansas Post lost any importance it had left and became mostly a farming area.

The Union victory helped stop Confederate trouble on the Mississippi River. It also helped the Union win the battle at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

While the Confederates controlled the post, the state bank building was used as a hospital. Parts of the Confederate road, trenches, and cannon positions from this time are still visible at the memorial site.

About the Arkansas Post National Memorial

The Arkansas Post National Memorial is a protected area of about 757 acres in Arkansas County, United States. The National Park Service manages most of the land. The Arkansas Department of Parks, Heritage, and Tourism manages a museum on the rest of the grounds.

The Memorial remembers the rich history of many cultures and times. These include the Quapaw people, the first French settlers, the short time of Spanish rule, a small fight during the American Revolutionary War in 1783, and its role as the first capital of Arkansas. It also remembers an American Civil War battle in 1863.

The old site of Arkansas Post became a state park in 1929. It started with 20 acres given by Fred Quandt. His family, descendants of German immigrants, still lives in Arkansas. More land was bought later. Many improvements were made with help from a government program called the Works Progress Administration.

On July 6, 1960, the site was named a National Memorial. It became a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960.

Discovering History Through Archaeology

From 1956 to 1957, Preston Holder led the first archeological digs at the site. His team found remains of the French colonial village from the 1700s. They found trenches that showed how French colonial houses were built, using wooden posts in the ground. By this time, the remains of the 1752 French fort, Fort Carlos III, the 1790s Fort San Estevan, and Fort Hindman were all underwater. They were in the old Arkansas River channel, now a lake for boats. There is no archeological evidence left for those forts because of the river washing them away.

In 1964, the National Park Service partly rebuilt some colonial remains. This included Fort Carlos III, built by the Spanish. More archeological digs of the colonial settlement happened in 1966 and from 1970 to 1971. Buildings from the 1800s were found, like the state bank and homes. Most homes were built in a French or Spanish style. However, a house's look often depended on the culture of the person living there. Thousands of broken pieces of pottery were also found.

John Walthall, the state archeologist for Arkansas, said in the 1990s that the archeological finds are the most valuable historical items at the memorial. This includes Quapaw villages that haven't been fully studied. It also includes the European and American settlements from the 1700s and 1800s. Archeological work has been more successful in the northern part of the site. This is because it was less likely to be washed away or flooded. No physical traces of the post's old riverfront remain due to erosion.

More to Explore

- List of French forts in North America

- List of newspapers in Arkansas

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Arkansas

- List of national memorials of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Arkansas County, Arkansas

See also

In Spanish: Puesto de Arkansas para niños

In Spanish: Puesto de Arkansas para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |