Thomas C. Hindman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

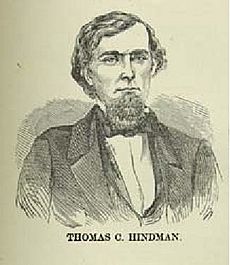

Thomas C. Hindman

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arkansas's 1st district |

|

| In office 1859–1861 |

|

| Preceded by | Alfred B. Greenwood |

| Succeeded by | Logan H. Roots (1868) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Thomas Carmichael Hindman Jr.

January 28, 1828 Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | September 28, 1868 (aged 40) Helena, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Maple Hill Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Mary Watkins Biscoe

(m. 1856) |

| Children | 5 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | United States Volunteers |

| Years of service | 1846–1848 (USV) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

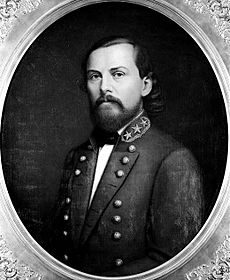

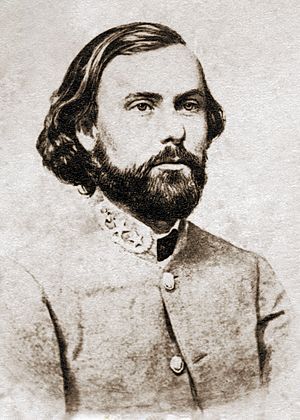

Thomas Carmichael Hindman Jr. (born January 28, 1828 – died September 28, 1868) was an American lawyer and politician. He also served as a high-ranking officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, Hindman later moved to Mississippi. There, he became involved in politics. He fought in the Mexican–American War from 1846 to 1848. After the war, Hindman became a lawyer. In 1853, he was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives. When his term ended in 1854, he moved to Helena, Arkansas, seeking more political chances.

Hindman quickly became a political leader in Arkansas. He opposed the Know-Nothing party and the powerful Conway-Johnson political group. In 1858, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He supported slavery and the idea of states leaving the Union. When the American Civil War began in 1861, Arkansas left the Union. Hindman joined the Confederate Army. He first led the 2nd Arkansas Infantry Regiment. Later, he commanded a larger group of soldiers at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, where he was wounded.

After Shiloh, Hindman was promoted to major general. He was sent to the Trans-Mississippi Department. This area included Arkansas, Missouri, the Indian Territory, and parts of Louisiana. As commander, Hindman's actions were sometimes questioned, but he successfully built up the region's defenses. Public complaints led to his removal from this command. He was defeated at the Battle of Prairie Grove in December. In 1863, he moved to the Army of Tennessee. He led a division at the Battle of Chickamauga in September, where he was wounded again. After healing, he commanded a division during the early parts of the Atlanta campaign.

In the summer of 1864, Hindman was injured during the retreat after the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. He took time off and traveled to Texas with his family. When the Confederacy lost the war in 1865, he fled to Mexico. He returned to Helena in 1867. He again became involved in politics, opposing the new state government during the Reconstruction Era. Hindman was shot at his home on September 27, 1868. He died the next morning. Before he died, Hindman believed the shooting was for political reasons.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Carmichael Hindman Jr. was born on January 28, 1828. His parents were Thomas C. Hindman Sr. and Sallie Holt Hindman. His family had English and Scottish roots. His father served in the War of 1812. The family moved to Jacksonville, Alabama, in 1841.

Thomas Jr. was sent to New York to live with relatives. He later attended the Lawrenceville Classical Institute in New Jersey. His studies focused on English, Greek, Latin, math, and history. He also learned about debate and public speaking. Hindman graduated in 1843 with high honors.

After school, Hindman moved to Ripley, Mississippi. His family had moved there while he was away. In Mississippi, Hindman farmed cotton. He also studied law with a local lawyer named Orlando Davis. In 1846, the Mexican–American War began. Hindman felt strongly about the war and wanted to join.

Serving in the Mexican-American War

In 1846, President James K. Polk asked states for volunteer soldiers. Mississippi's Governor Albert G. Brown formed several companies. But Mississippi was only allowed to send one unit, the Mississippi Rifles. This meant many volunteers, including Hindman, could not join.

Later, Mississippi was allowed a second infantry unit. Hindman and his older brother Robert joined. Thomas served as a second lieutenant. His brother Robert left the army due to health issues.

Hindman's unit, the 2nd Mississippi, trained in January 1847. They then moved to New Orleans, Louisiana. The unit traveled to the Rio Grande River in February. They also went to places like Saltillo and Buena Vista. The unit saw little direct fighting. Instead, many soldiers became sick. Hindman served well as a junior officer.

Returning to Mississippi Politics

Hindman's regiment returned to Mississippi in 1848. In May 1849, his brother Robert was killed in a fight. Thomas Jr. later had a gunfight with the same person, but no one was hurt. A duel was almost fought between them.

Hindman joined the Sons of Temperance, a group that promoted avoiding alcohol. He became active in the early 1850s. After finishing his law studies, he became a lawyer in 1851. But he found his true passion in politics.

A big political topic in Mississippi in 1851 was whether slavery should be allowed in new territories. Hindman supported expanding slavery. He became a delegate for the Democratic Party. He was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1853. He supported tax and education changes. He also supported the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. His term ended in March 1854. This was the end of his political career in Mississippi.

Moving to Arkansas

In 1854, Hindman felt Mississippi's politics were too crowded. He saw more chances in Arkansas, which was less developed. He moved to Helena in June 1854. He quickly became involved in Arkansas politics. He started a law firm with John Palmer.

Hindman gained attention in a political debate on July 4. He was known for his fancy style. After a debate, a local politician insulted him. They almost dueled with bowie knives, but friends stopped them. In 1854, Hindman spoke about railroads that would help Helena. He did not run for office that year.

In 1855, Hindman continued to support temperance groups. He became more active in Arkansas politics in May 1855. He opposed the Know-Nothings. This group was against immigrants and Catholics. Hindman opposed them because they were against slavery. He also disagreed with their views on immigration and religious freedom.

Hindman formed a Democratic Party group. He spent the rest of 1855 speaking against the Know-Nothings. He held a big rally in Helena in November. During a yellow fever outbreak in Helena, Hindman and his friend Patrick Cleburne helped as nurses. They became close friends. They bought a newspaper together and called it the States Rights Democrat.

In 1856, Hindman decided to run for Congress. He campaigned across northern Arkansas. He spoke against the Know-Nothings and the idea of ending slavery. He faced Alfred B. Greenwood for the Democratic nomination. After many rounds of voting, Hindman withdrew to help party unity. Even so, he actively campaigned for Greenwood.

Hindman's strong opposition to the Know-Nothings led to a conflict with state politician W. D. Rice. In May 1856, Rice and his relatives fought Hindman and Cleburne in the street. Everyone was armed. Rice shot Hindman in the arm and side. Hindman and Cleburne shot back. Cleburne was shot in the lung. One of Rice's relatives died. Both Hindman and Cleburne were found not guilty for their actions.

In 1856, Hindman began dating Mary Watkins Biscoe. They married on November 11. Cleburne was Hindman's best man. Mary's father was a rich landowner. Her uncles had held state offices. This marriage helped Hindman's money and social standing.

Changing Arkansas Politics

Hindman ran for Congress again in late 1857. The Know-Nothings had lost power. Hindman was popular with Arkansas Democrats. He easily won his party's nomination. He then won the election against William M. Crosby. During the campaign, he broke his leg in a carriage accident. The injury made one leg two inches longer than the other. He had to wear a special boot and walked with a limp for the rest of his life.

For many years, Arkansas politics had been controlled by a group called "the Family." By the late 1850s, their power was weakening. Hindman wanted to become a Senator. He led a Democratic group called the Old Line Democrats, which opposed the Family. Hindman also started a newspaper called the Old Line Democrat.

In November 1858, a political meeting changed rules for choosing candidates. Hindman protested, believing it was to help a Family member. The Family leaders threatened to stop Hindman's re-election. They saw Hindman as a troublemaker.

Hindman and the Family disagreed on money matters. A state bank had failed, leaving Arkansas in debt. Hindman suggested collecting money from the bank's debtors. Many of these debtors were Family members. The Family accused Hindman of trying to help his father-in-law, who owed the bank money. Hindman also said the state unfairly gave a printing contract to a Family-owned newspaper. The Family said Hindman just wanted the contract for his own newspapers.

In November 1859, Hindman promised to speak against the Family in Little Rock. But he went to Mississippi instead, saying his family was sick. This led to more arguments. Another fight almost happened between Hindman and Robert Ward Johnson. Hindman later admitted to writing letters that supported himself under a fake name.

Hindman's rise caused problems in Arkansas politics. The state Democratic Party was split. In 1860, the Family leaders tried to control who would be nominated for governor. But Henry Massey Rector, a lower-ranking Family member, entered the race. Hindman supported Rector. Hindman easily won his own nomination for Congress. Rector defeated the Family's candidate for governor. Hindman also won his election. The 1860 elections ended the Family's power in Arkansas politics.

American Civil War Service

Arkansas Leaves the Union

Throughout his political life, Hindman supported slavery. He believed the United States should allow slavery to continue. He also supported bringing back the international slave trade, which was against the law. In 1859, Hindman and other Southern Democrats opposed Republican John Sherman for Speaker of the House. Sherman had supported an anti-slavery book. In January 1860, Hindman gave a speech against Sherman. His speech was popular in the South.

In Congress, Hindman supported a canal on the Red River of the South. He also wanted to lower the cost of public land. He supported a railroad from Memphis, Tennessee to Albuquerque. He also suggested turning the Little Rock Arsenal into a school.

In 1860, the Democratic Party split. Hindman supported John C. Breckinridge, who was seen as more supportive of slavery. Breckinridge won Arkansas, but Republican Abraham Lincoln won the national election. Hindman believed Lincoln's election meant slavery was no longer safe. He supported states leaving the Union, even if it meant war.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina left the Union. The next day, Hindman asked Arkansas to hold a meeting about leaving the Union. By January 1861, several Southern states had left. Arkansas took control of the Little Rock Arsenal in February. On February 18, Arkansas voters approved a meeting about secession. This meeting first voted against leaving the Union. But they agreed to hold a public vote on secession in August.

Things changed in mid-April. On April 12, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter. This started the American Civil War. President Lincoln asked states for soldiers to stop the rebellion. Arkansas refused. Public opinion in Arkansas shifted towards leaving the Union. Hindman gave speeches supporting secession. On May 6, the convention voted for Arkansas to leave the Union. Hindman told Confederate President Jefferson Davis the news. With war starting, Hindman resigned from Congress. Historians say Hindman played a big part in Arkansas leaving the Union.

Joining the Confederate Army

After Arkansas left the Union, the state prepared for war. Hindman helped write a plan to create a military board. He got permission to recruit a regiment for the Confederate Army. Hindman had to pay for his men's weapons, food, and clothes himself.

His unit became the 2nd Arkansas Infantry Regiment. Hindman joined the Confederate States Army as a colonel on June 12. His men were assigned to General William J. Hardee. Other Arkansas troops stayed in state service. Many went home because they were not paid or clothed.

In September, General Albert Sidney Johnston took command of all forces west of the Allegheny Mountains. Hardee's force, including Hindman's regiment, moved to Kentucky. Hindman was recruiting and joined them later. He was promoted to brigadier general on September 28. In Kentucky, Hindman's men fought in small battles, like the Battle of Rowlett's Station in December.

Fighting at Shiloh

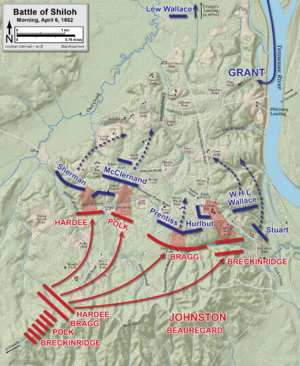

In February 1862, after Union victories, General Johnston ordered his army to leave Kentucky. Hindman's men moved to Corinth, Mississippi. At Corinth, Johnston gathered over 40,000 men. He planned an attack on Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Union army at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. This attack was the Battle of Shiloh, launched on April 6.

Hindman commanded a group of soldiers in Hardee's corps. The battle started with Hindman's men fighting a Union brigade. This stopped the Confederates from surprising the Union completely. Hindman personally led another attack that broke a Union brigade. During the fighting, Hindman's horse was killed. He fell and broke a leg, taking him out of the battle.

Union forces were pushed back but not fully defeated. Union reinforcements arrived the next day. They drove the Confederates from the field. Hindman received praise for his actions at Shiloh.

Commanding the Trans-Mississippi Department

After Shiloh, Hindman went home to Helena to recover. He was promoted to major general on April 14. On May 26, he was ordered to command Arkansas and the Indian Territory. These orders soon expanded to include Missouri and parts of Louisiana. Hindman arrived in Little Rock on May 30. Most soldiers and supplies in the Trans-Mississippi Department had been moved east of the Mississippi River. Arkansas was left with very little.

Hindman had to build his department from almost nothing. He worked with great energy. He made sure men joined the army. He encouraged guerrilla warfare, which is fighting in small, unofficial groups. He also declared martial law, meaning the military took control. He took troops passing through the state. He ordered all white troops in the Indian Territory to Arkansas. He set up places to make supplies and weapons. He also brought back Missouri troops that had been sent east. He reorganized the cavalry units.

Hindman's actions helped make the cavalry useful. However, his policies on guerrilla warfare later caused more lawlessness in the state. He also set up defenses on the White River. But Union forces won battles there and took Helena. Helena was the only permanent loss of land for the Confederates in Arkansas at that time.

Hindman's methods were sometimes outside the law. He angered many powerful people in Arkansas. Plantation owners objected when Hindman ordered cotton burned to keep it from Union forces. They also disliked him taking enslaved people for military building projects. Joining the army was unpopular. Many Arkansans saw him as a harsh leader.

Hindman also had problems with Brigadier General Albert Pike. Pike disagreed with moving his white troops from the Indian Territory. Hindman supported another officer who ordered Pike's arrest. Arkansas leaders complained about Hindman to the Confederate government. Hindman was replaced by Major General Theophilus Holmes on July 16. Holmes arrived in Arkansas on August 12.

Battle of Prairie Grove

Holmes kept some of Hindman's unpopular rules, like martial law. Holmes divided his department into three areas. Hindman was given command of the District of Arkansas. This included Arkansas, Missouri, and the Indian Territory. Both Holmes and Hindman wanted to invade Missouri. Hindman was ordered to Fort Smith to prepare for this.

The Confederate troops were not ready for a big attack. Only a few months were left before winter made travel hard. In early September, Hindman moved 6,000 men into southwestern Missouri. He set up his headquarters at Pineville. On September 10, Holmes called him back to Little Rock. Hindman was needed for administrative tasks.

While Hindman was away, Brigadier General James S. Rains took command. The Confederates in Missouri retreated into Arkansas. Hindman returned to Fort Smith in mid-October. He had Rains removed from command. Hindman learned that Union Major General John Schofield had entered Arkansas with many men. Hindman moved his force south. Schofield then took two of his divisions back to Missouri. He left Brigadier General James G. Blunt's division in northwestern Arkansas.

The Confederates had lost a battle at Corinth. Holmes was ordered to send 10,000 men east of the Mississippi River. Hindman disagreed. He suggested an attack instead. Holmes agreed. Hindman's plan was to send cavalry to Cane Hill to distract Blunt. Then, he would move most of his force behind Blunt, defeating him before Union help arrived.

Union scouts found the cavalry. Blunt moved to attack the Confederate cavalry. Fighting broke out on November 28. The Confederate cavalry had to retreat. Hindman then moved most of his force, about 11,000 men, towards Cane Hill on December 3. Blunt learned of this and prepared for a fight.

On December 6, Hindman learned that Union forces, led by Brigadier General Francis J. Herron, were already on their way. They would be at Cane Hill on December 7. Hindman changed his plan. He decided to attack Herron at Prairie Grove on December 7. Then he would attack Blunt. This new plan was risky. It depended on Blunt not moving to help Herron.

Hindman did not attack. Instead, he took a defensive position at Prairie Grove on December 7. The Battle of Prairie Grove began between Hindman and Herron. Blunt arrived on the field later that day. The Confederates fought Herron and Blunt to a draw. But Hindman decided to retreat to Van Buren, Arkansas, after the battle. Historians say Hindman's decision to play defense was a big mistake. The Confederates retreated again after a defeat at the Battle of Van Buren on December 28. They went to Little Rock.

Battle of Chickamauga

Hindman's past actions and the defeat at Prairie Grove made him unpopular. Arkansas politicians asked President Davis to move him out of the state. This request was granted on January 30, 1863. Hindman was assigned to a special court. He left Arkansas on March 13. He was then sent to command a division in Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk's corps of the Army of Tennessee. He arrived in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on August 13. But he soon had a bad relationship with the army commander, General Braxton Bragg.

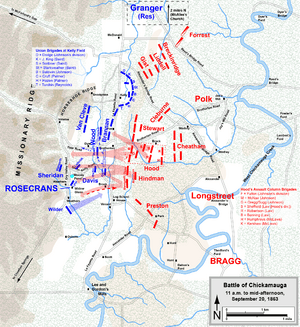

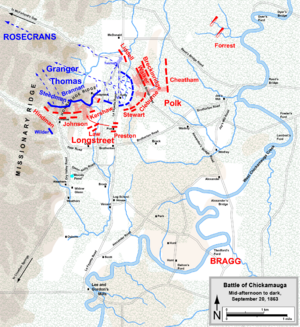

On August 16, Union Major General William Rosecrans began moving towards Chattanooga. Bragg's army was outnumbered. He left Chattanooga and moved into northern Georgia. Rosecrans followed, but stretched his army too far. Bragg saw a chance to attack.

On September 9, Bragg ordered Hindman to attack a Union division. He also ordered D. H. Hill to send another division to attack from the other side. Hill said this was not possible. Hindman's division also stopped early. He sent a message to Bragg saying he would not move further unless he knew the other division was moving too. Hindman continued his movement on September 11. Bragg ordered an attack but then changed his mind. There was only light fighting. Hindman's actions were seen as poor.

Bragg then decided to attack Rosecrans at Lee and Gordon Mill. The Battle of Chickamauga began on September 18. The main Confederate attack started on September 19. Hindman's division was on the left side of the Confederate army. The battle continued on September 20. A mistake caused a gap in the Union lines. Confederate troops attacked into this gap.

Hindman's division quickly broke two Union divisions. The entire Union right side collapsed. Hindman was wounded in the neck by a piece of metal. But he stayed on the field. Later, a Union brigade attacked Hindman's left side, stopping his division's attack. Fighting continued until nightfall. The Union forces retreated. Bragg decided not to chase them.

Suspension and Transfer

On September 29, 1863, Bragg removed Polk and Hindman from command. Hindman was accused of not obeying orders. This was related to the earlier incident where he stopped his advance. Hindman was sent to Atlanta to wait. Historians say the suspensions were unfair. They might have been because Bragg wanted to get rid of critics.

After recovering, Hindman prepared documents to fight his suspension. He asked for a review of his case. Many officers and civilians criticized Bragg's leadership. President Davis said the suspensions of Hindman and Polk were invalid. Bragg later dropped the charges against Hindman. Hindman was allowed to take leave until December 15. Meanwhile, Bragg was removed from command. General Joseph E. Johnston replaced him. Hindman temporarily commanded a corps until Major General John Bell Hood arrived.

Over the winter of 1863-1864, Hindman supported arming enslaved people for the Confederacy. This was a very controversial idea and was rejected. Hindman did not want to serve under Hood. He asked for a transfer to another job or a different location. His request was denied. His support for arming enslaved people and his past unpopularity in Arkansas hurt his chances for promotion. His resignation was denied on March 23. Hindman officially returned to command his division on April 3.

Atlanta Campaign Battles

In early May 1864, Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman began the Atlanta campaign. He moved nearly 100,000 men against Johnston's army in northern Georgia. The Confederates retreated from Dalton, Georgia, to Resaca. The Battle of Resaca began on May 13. Hindman's division was attacked. They pushed back the Union soldiers. The battle continued on May 14 and 15.

Union cavalry attacked the Confederate rear. They hit Hindman's field hospital, destroying supplies and taking prisoners. Union troops attacked Hindman's line again, but were pushed back. Johnston learned that Union troops were threatening his supply lines. He ordered a retreat that night.

The Confederate retreat continued with some fighting. Johnston took up a new position in the Marietta area in June. On June 22, Union troops attacked Hood's division near Kolb's Farm. Hood ordered an attack. The Battle of Kolb's Farm was a bloody defeat for the Confederates. Hindman's division was ordered to charge. They ran into a swamp and were driven back.

On June 27, Sherman was defeated in attacks at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. He then moved around Johnston's army, forcing the Confederates to retreat. During the retreat from Kennesaw Mountain, Hindman was hit in the face by a tree branch. He fell from his horse and was injured. He had severe eye problems. The eye injury stopped him from leading in the field. Hindman went to Atlanta and then Macon to recover.

Time in Texas and War's End

On July 10, 1864, Hindman again asked for a transfer, specifically to the Trans-Mississippi. This was denied because he was still unpopular in Arkansas. He was offered time off to recover from his injury. Hindman chose San Antonio, Texas for his leave. He expected to be out of action for several months.

To support his family in Texas, Hindman bought tobacco in Alabama. He had it shipped to Texas using Confederate military wagons. He planned to sell it there. He left with his family in late August. One of his daughters died of illness during the trip. In November, they crossed the Mississippi River. They arrived in Shreveport, Louisiana. Hindman was criticized for using military wagons for his personal goods, but it was a common practice.

The Hindmans reached San Antonio in January 1865. By this time, the Confederacy was losing the war. False rumors spread about Hindman. In April, the main Confederate armies surrendered. General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered to Union forces on June 2. Hindman, who faced charges from Union authorities in Arkansas, refused to surrender. With his family and other Confederates, Hindman left Texas in June. They crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico. The Hindmans settled in Monterrey.

Life After the War

Hindman hoped to easily start a law practice in Mexico. But he had trouble finding work, even after learning Spanish. The Mexican leader, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, ordered the ex-Confederates to leave Monterrey. He worried they would become too powerful. The Hindmans moved to Saltillo and then Montelise.

They traveled to Mexico City in September. Hindman hoped to talk to Maximilian about land for the Confederate refugees. The Hindmans became friends with Maximilian and his wife Carlota of Mexico. Hindman's fifth child was born in Mexico City in December. Hindman also published two books about military ideas. The family later moved to Carlota, where many ex-Confederates settled.

In Carlota, farming did not go well. Hindman could not start a successful law practice because people were poor. Hindman was part of a plan in 1866 to start a colony in the Yucatán Peninsula. But this failed when foreign support for Maximilian ended. The family moved to Orizaba before June. Rebels against Maximilian destroyed Carlota soon after they left. Maximilian's rule collapsed. The Hindmans had to return to the United States. They returned to Helena in April 1867. Hindman asked for a pardon from President Andrew Johnson, but it was denied. In Helena, Hindman started his law practice again.

Hindman also re-entered politics. He spoke against the Radical Republicans. He also argued against the 1868 Arkansas Constitution. He opposed the Republican candidate for governor, Powell Clayton. To try and silence Hindman, Republican leaders in Arkansas brought back the 1865 charges against him. Hindman was arrested on March 20, 1868. He was allowed to remain free until his trial. But the charges meant he was not included in a July 1868 pardon for most former Confederates.

He then became the leader of a political group called the Young Democracy. This group supported taking a loyalty oath and participating in future elections. The Young Democracy claimed that Republicans were using Reconstruction for their own gain. They said that formerly enslaved people should support the Democrats. Hindman began to gain followers, both former Confederates and formerly enslaved people.

Assassination

On the night of September 27, 1868, Hindman was sitting in his home with his children. He was shot through a window. He was hit in the neck and jaw. His wife carried him outside. Neighbors gathered around. Hindman believed the shooting was for political reasons. He asked a relative to take care of his family. He died early the next morning. His assassination shocked Arkansas.

Many people blamed the Republican Party for the murder. But the person who shot him was never found. In 1876, a person in Georgia claimed to have murdered Hindman. But his story did not match the known facts. Hindman is buried at Maple Hill Cemetery in Helena. Hindman Hall, a museum at Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, was built with money left by Hindman's son for a memorial.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of United States representatives from Arkansas

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |