Battle of Borgerhout facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Borgerhout |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

Engraving of the Battle of Borgerhout by Frans Hogenberg, 1579–81. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

For the Union of Utrecht: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alexander Farnese, Prince of Parma | François de la Noue John Norreys |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 infantry and cavalry, 2 or 3 cannons | 3,000–4,000 infantry, 100 cavalry, unknown artillery | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Max. 500 killed | Max. 1,000 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Borgerhout was an important fight during the Eighty Years' War. It happened on March 2, 1579. The Spanish Army, led by Prince Alexander Farnese, attacked a fortified camp. This camp was in the village of Borgerhout, near the city of Antwerp.

Inside the camp were thousands of soldiers from France, England, Scotland, and Wallonia. They were fighting for the Union of Utrecht, a group of Dutch provinces. This battle was part of Spain's effort to take back control of the Burgundian Netherlands. These provinces had joined together in 1576 under the Pacification of Ghent. Their goal was to remove foreign troops and allow religious liberty for Protestants.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After a rebel victory in July 1578, the Spanish Army still took back much of the southern Netherlands. The city of Brussels was in danger. So, the States General (the Dutch government) moved to the safer city of Antwerp.

Prince Farnese, the Spanish commander, noticed that the Dutch rebel army was not well-organized. He decided to attack the city of Maastricht. To trick the Dutch and also to scare the people of Antwerp, Farnese moved his troops. He aimed to surprise Borgerhout, a village very close to Antwerp.

Who Was There

A part of the Dutch army was staying in Borgerhout. This included 3,000 to 4,000 foot soldiers. They were the main strength of the rebel army. These soldiers included French Calvinists led by François de la Noue. There were also English and Scottish troops under John Norreys.

The Attack on Borgerhout

On March 2, Farnese spread out his army on a flat area. This area was between his position at Ranst and the Dutch camp in Borgerhout. Norreys and De la Noue had made their camp strong. They dug moats, built palisades (wooden fences), and made earthworks (dirt walls).

How the Spanish Attacked

The Spanish attack was split into three groups. Each group had a portable bridge to cross the camp's moat. One of the attacks, carried out by Walloon troops, successfully got a bridge across. This allowed the Spanish forces to get inside the camp.

Norreys and De la Noue's soldiers fought hard to defend their position. But Farnese sent his light cavalry (fast horsemen) into the battle. This forced the Dutch troops to leave Borgerhout. They ran for safety under the cannons of Antwerp's city walls. William of Orange, the leader of the Dutch revolt, watched the fight. He was on Antwerp's walls with Archduke Matthias of Habsburg. Matthias was the Governor-General of the Netherlands at the time.

After the Battle

The battle led to the destruction of Borgerhout and the nearby village of Deurne. About 1,500 soldiers from both sides were killed. After this victory, Farnese went on to besiege Maastricht. The Spanish Army attacked Maastricht less than a week later. They captured it on June 29 of the same year. Farnese's successful campaign started a nine-year period. During this time, Spain took back many parts of the Netherlands.

Why the War Started

The Eighty Years' War began due to several reasons. The Netherlands, which was part of the Habsburg empire, was ruled by Philip II of Spain. People were unhappy about religious differences between Protestants and Catholics. Also, the local nobles and cities did not want to pay for Philip's wars. They also didn't want to give up their power to the king's government.

In 1567, Philip sent an army to the Netherlands. It was led by the Duke of Alba. His job was to bring back order. But Alba treated religious and political rebels harshly. This caused William of Orange, a leader of the nobility, to flee to Germany. He then planned to invade the Netherlands to remove Alba.

Orange tried to invade twice, in 1568 and 1572. Both times, Alba defeated him. However, in 1572, the revolt spread to Holland and Zealand. Alba could not stop it. In 1576, there was no strong leader after Alba's replacement died. Also, Spain went bankrupt. This caused Spanish soldiers to riot and loot several towns, including Antwerp. Because of this, the loyal and rebel provinces joined together. They signed the Pacification of Ghent to force out the foreign troops.

New Leaders and Divisions

John of Austria, a famous Spanish commander, took over. He had to agree to the Pacification of Ghent in 1577. But he later became frustrated with William of Orange. John then took the citadel of Namur and called back his troops. John won a big victory at the Battle of Gembloux in January 1578. But he suffered a tactical defeat at Rijmenam in July. John himself died of plague in October.

Even with the Spanish defeat at Rijmenam, the victory at Gembloux helped Spain politically. It broke the unity of the Dutch rebels. Leaders in the southern provinces lost faith in Orange. They also doubted the promises of help from Queen Elizabeth I. This was a big setback for Orange.

To help the Dutch rebels, Elizabeth arranged for a German army to be raised. This army was paid by England and led by John Casimir. But John Casimir sided with extreme Calvinists. This made the split between Catholic and Protestant rebels even wider. The States General also asked for help from Francis, Duke of Anjou, the French king's brother. He came to Mons in July 1578 but soon returned to France.

The Union of Arras and Utrecht

The Catholic nobles and southern provinces started leaving the rebel cause in late 1578. The provinces of Hainaut and Artois formed the Union of Arras on January 6, 1579. Walloon Flanders soon joined them. The Catholic provinces of Namur, Luxembourg, and Limburg were already controlled by Spain.

The Union of Arras began talks with Alexander Farnese in February. Farnese had taken over as Governor-General after his uncle John of Austria died. They wanted to make peace with Philip II. In response, the northern provinces met in Utrecht. Holland, Zealand, Utrecht, Friesland, Gelderland, and Ommelanden signed an alliance on January 23.

Meanwhile, Farnese planned to capture Maastricht. He wanted to use its stone bridge over the Meuse river as a base. From there, he could conquer Brussels and Antwerp. In November 1578, the Spanish Army left Namur. They marched through the Ardennes and Limburg. But Farnese thought it was too risky to start the siege of Maastricht in winter. Also, John Casimir's large cavalry force was still in the area.

The Military Plan

For the 1579 military plan, Farnese had two main goals. One part of his army, led by Cristóbal de Mondragón, would clear Dutch troops from the area between Maastricht and the German border. Farnese himself, with the main army, would move toward Antwerp. His goals were to defeat the Dutch army before besieging Maastricht and to distract the Dutch from his real target.

The first part of the plan worked. Mondragón captured Kerpen, Erkelenz, and Straelen between January 7 and 15. On January 24, Farnese moved to attack the States General army. This army was in Weert, east of Antwerp. The Dutch commander, François de la Noue, was outnumbered. He left some troops in Weert Castle and retreated to Antwerp with his unpaid soldiers.

Where the Dutch Camped

De la Noue's soldiers asked to enter Antwerp, but the city council refused. So, De la Noue had to set up his army outside the city walls, in the village of Borgerhout. This area had country houses and gardens belonging to rich people from Antwerp. One famous garden belonged to Peeter van Coudenberghe, which had over 600 exotic plants.

Farnese then sent Count Hannibal d'Altemps to capture Weert. D'Altemps surrounded Weert with 6,000 men and broke its walls with two cannons. The castle defenders surrendered, but Farnese ordered them to be executed. Farnese then stayed in Turnhout to gather supplies. Before moving to Antwerp, he dealt with John Casimir's German army. Spanish troops attacked and defeated some German horsemen near Eindhoven on February 10.

While John Casimir was in England, Farnese made a deal with his second-in-command, Maurice of Saxe-Lauenburg. Maurice agreed to withdraw the Calvinist army, and the Spanish allowed them to leave the Netherlands freely. Once this was done, Farnese advanced on Borgerhout.

Troops and Positions

The Dutch States' troops in Borgerhout had about 25 to 40 infantry companies. This meant 3,000 to 4,000 soldiers, plus 100 mounted troops. These were the strongest part of the rebel army. William of Orange called them "his braves." They were led by skilled officers like François de la Noue and John Norreys.

To face the Spanish, they spread out along Borgerhout. They had fortified the village by digging a moat and building an earth rampart around it. This defense stretched from the bridge of Deurne over the Groot Schijn stream to the road of Voetweg.

Antwerp's Defenses

Orange also placed four more French infantry groups and Walloon troops behind Borgerhout. These came from nearby garrisons and were protected by Antwerp's citadel and moat. The city's civic guard (armed citizens), with 80 groups of trained fighters, was ready to defend Antwerp. However, they were not willing to join the battle outside the walls. They also would not let the regular troops enter Antwerp.

A Spanish soldier and writer, Alonso Vázquez, claimed that Orange's army had 25,000 men in total. Farnese used a 5,000-man advance force of both foot soldiers and cavalry. This force was in the flat area between his camp at Ranst and Borgerhout.

Spanish Battle Formations

Three small groups, each with no more than 12 companies but made of chosen men, went first. The right side was taken by the Spanish `tercio` (a large infantry unit) of Lope de Figueroa. The center had a German regiment under Francisco de Valdés. The right had a Walloon regiment under Claude de Berlaymont, also known as Haultpenne.

Each group had 100 musketeers (soldiers with muskets). They also had men with axes to cut down wooden fences and a wheeled bridge to cross the moat. A group of light cavalry led by Antonio de Olivera followed the foot soldiers. Their job was to cover a retreat if the attack went badly, or to push forward if they won.

According to Alonso Vázquez, Farnese made the Walloon soldiers in the Spanish army wear white shirts over their armor. This was common in night attacks, called `camisades`, to tell them apart from the Walloons fighting for the Union of Utrecht. Vázquez said they looked like "a very colorful procession of clerics and sacristans."

In reserve, Farnese had a large group of German regiments. These were led by Hannibal d'Altemps and Georg von Frundsberg. On their right were horsemen under Duke Francis of Saxe-Lauenburg. On their left were lancers (soldiers with lances) under Pierre de Taxis. The rest of the Spanish cavalry, led by Ottavio Gonzaga, covered the rear. Farnese led his troops himself. Before the battle, he scouted the Dutch positions. He told his troops not to move until he returned.

On the Dutch side, De la Noue and Norreys led the men in Borgerhout. William of Orange watched the battle from Antwerp's walls. He was with Archduke Matthias, the Holy Roman Emperor's brother. The States General had chosen Matthias as Governor of the Netherlands.

The Battle Unfolds

The fight began with the three Spanish groups moving toward the Dutch camp. Each group tried to be the first to put its bridge over the moat. Haultpenne's Walloons, led by Sergeant-Major Camille Sacchino, moved to Deurne. They crossed the Schijn river at the small village of Immerseel. Valdés' Germans advanced directly on Borgerhout along the Borsbeek road. Figueroa's Spaniards took the Voetweg road to attack the Dutch camp from the south.

The musketeers from the Spanish and German units exchanged fire with the Dutch troops. The Dutch were protected by their rampart. Sacchino's Walloons pushed the defenders of Deurne back behind the Groot Schijn stream. They then took its bridge.

De la Noue sent more soldiers to help, but they arrived too late. The Walloons had already put their bridge over the moat. They began to climb the rampart, starting a close fight with the Dutch troops. Meanwhile, the Spanish and German troops, supported by two or three artillery pieces, broke through the rampart. They crossed the moat and entered Borgerhout. De la Noue and Norreys' men regrouped and fought in the barricaded streets.

Spanish Victory

Farnese saw that his attack was going well. He ordered Olivera to advance with his cavalry to support the foot soldiers. The light horsemen entered Borgerhout through the gap made by Figueroa's men. Farnese himself took command of Taxis' lancers and entered through Valdés' path. The French and English soldiers fought strongly. But after two hours of fighting inside the camp, De la Noue began to pull his forces back to Antwerp. He wanted to avoid his army being completely destroyed.

The retreating troops set fire to their living areas. They sought safety under the protection of Antwerp's cannons. Many Spanish soldiers chased them, even though their officers told them to stay together. They chased the rebels all the way to Antwerp's moat.

At William of Orange's orders, the cannons on the city walls fired shrapnel (small metal pieces) at the Spanish troops. The results are described differently by various sources. The Spanish soldier Alonso Vázquez said the shots were not effective. He claimed the battlefield was covered by smoke from the burning Borgerhout. However, the Flemish official Guillaume Baudart said the shots were accurate. He claimed they made "arms and legs fly on the air."

By then, Farnese did not want his troops to stay near Antwerp's cannons for long. He ordered drums and trumpets to signal a retreat. He gathered his men in Borgerhout. Meanwhile, people from Antwerp came out to carry the wounded French, British, and Walloon officers and soldiers into the city for treatment.

Once the fire in Borgerhout was out, the Spanish soldiers looted the basements of the burned buildings. They then ate a meal and prayed to thank God. After that, the Spanish army marched along the roads to Lier and Herentals, heading for Turnhout. Farnese wanted to reach Turnhout the next day. Fearing another attack, Antwerp's civic guards stayed at their posts all night.

Impact of the Battle

The number of soldiers killed in the battle varies depending on who wrote about it. The Italian Jesuit Famiano Strada wrote that Farnese, in a letter to his father Ottavio, said the Dutch lost 600 men killed. He also said his own troops lost eight men killed and 40 wounded. Strada also mentioned that other estimates said 1,040 Dutch soldiers were killed. On the other hand, the Flemish writer Guillaume Baudart said the Dutch lost 200 men killed. He claimed the Spanish army lost 500 men.

The villages of Deurne and Borgerhout were badly damaged by fire during the battle. In 1580, Deurne had 133 standing buildings, but 146 had been destroyed by fire. In Borgerhout, 206 buildings remained, and 280 were ruined.

Farnese's attack achieved its goal of distracting the Dutch forces from Maastricht. After the battle, the Spanish army quickly moved to Turnhout. They captured the castle of Grobbendonk along the way. They appeared before Maastricht on March 8, just six days after the Battle of Borgerhout. François de la Noue followed the Spanish with some troops, but when he realized Farnese was going to besiege Maastricht, it was too late to send more soldiers to defend the city.

Challenges for the Dutch

Also, mutinies (rebellions by soldiers) and defections (soldiers leaving their side) made it harder for the Dutch to save Maastricht. The English soldiers under John Norrey's command, who stayed outside Antwerp, kidnapped the abbot of St. Michael's Abbey. They demanded their unpaid wages. William of Orange had to step in to calm them down.

Politically, the battle caused more Walloon soldiers to leave the States General and join the Spanish side in the following months. Emanuel Philibert de Lalaing joined the Spanish Army with 5,000 Walloon troops from the Dutch States army. He then drove out a garrison loyal to the States General from Menen.

Farnese besieged Maastricht with 15,000 foot soldiers, 4,000 cavalry, 20 cannons, and 4,000 sappers (engineers who dig tunnels). Later, 5,000 more troops joined him. In May, while the siege was happening, peace talks were held in Cologne. The Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf tried to help keep the Netherlands united. However, the divisions became even worse during these talks.

Civil War and Spanish Reconquest

In Brussels, fighting broke out in early June. It was between Catholics led by Philip of Egmont and Calvinists under Olivier van den Tympel. This led to Egmont and his supporters being expelled. In Mechelen, the Catholic people forced the Dutch soldiers to leave. In 's-Hertogenbosch, fighting resulted in the city leaders supporting the Spanish king.

The revolt turned into a civil war. Because of the religious problems, the peace conference in Cologne failed. After this, Farnese began to take back Flanders and the Brabant town by town. He even forced Antwerp to surrender in 1585 after a long and difficult siege.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Borgerhout para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Borgerhout para niños

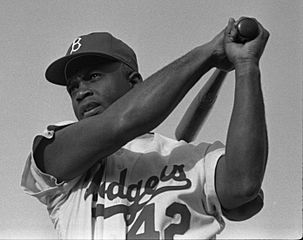

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |