Battle of Landen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Landen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nine Years' War | |||||||

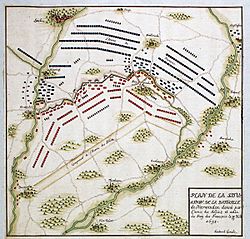

Map of the battle. The Allied armies are in red. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 66,000-70,000 70 guns |

50,000-60,000 80-100 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000 to 10,000 killed or wounded 15,000 killed or wounded |

9,500 killed, wounded or captured, plus 80 guns 12,000 to 14,000 killed, wounded or captured plus 60 guns 16,500 killed, wounded or captured, plus 84 guns 18,000 to 20,000 killed, wounded or captured, plus 80 guns |

||||||

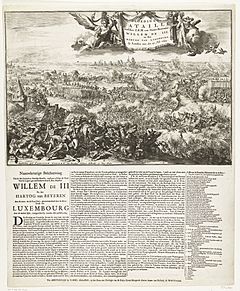

The Battle of Landen, also known as Neerwinden, happened on July 29, 1693. It was a major battle during the Nine Years' War. The battle took place near Landen in what is now Belgium.

A French army, led by Marshal Luxembourg, fought against an Allied army. The Allied forces were led by William III, who was King of England and ruler of the Dutch Republic. The French won the battle.

By 1693, all the countries fighting in the war were having money problems. They were also running out of supplies. King Louis XIV of France wanted to end the war with a good peace deal for France. To do this, he decided to attack first and try to win a big victory.

Marshal Luxembourg, the French commander in the Spanish Netherlands, saw a chance to fight William's army near Landen. The Allied army was in a strong position. However, it was also very risky because a river was behind them.

Most of the fighting happened on the Allied right side. This area was near the only bridge over the river. It was well-protected and had most of the Allied cannons. The French attacked this spot three times. Finally, they broke through the defenses. The Allies had to retreat and leave their cannons behind.

Even though France won, both sides lost many soldiers. This battle was similar to the Battle of Steenkerque the year before. King Louis XIV did not get the big win he needed to force the Allies to make peace. William quickly got new soldiers. By 1694, his army in Flanders was bigger than the French army for the first time in the war.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Nine Years' War was a big conflict in Europe. Since it started, the French army had generally done well in the Spanish Netherlands. They captured Namur and stopped an Allied surprise attack at Steenkerque in 1692. However, they had not won a decisive victory. They also failed to break up the Grand Alliance, which was a group of countries fighting against France.

Attempts to bring back James II as King of England had failed. This happened after the Treaty of Limerick in 1691. Then, the English and Dutch navies won a big sea battle at La Hogue in 1692. For a while, it seemed like the Allies were gaining the upper hand.

However, all sides were struggling with money and food shortages. This was made worse by the "Little Ice Age," a period of colder weather. After several bad years, the harvest failed completely in 1693 across Europe. This caused a terrible famine. It was very hard to feed large armies during these times.

Armies had grown much larger during this period. In 1648, an army might have 25,000 soldiers. By 1697, some had over 100,000. It was very difficult for countries to support such large armies.

These problems especially affected France. France was fighting on many fronts at once. King Louis XIV wanted peace, but he always tried to improve his position before talking about it. He had two main advantages: he was the only commander, and his army was much better at moving supplies. This meant the French could attack earlier than the Allies. They could quickly achieve their goals and then defend their positions.

In 1693, Louis XIV decided to attack in the Rhineland, Flanders, and Catalonia. When the attack in Germany went better than expected, Marshal Luxembourg was told to send 28,000 of his soldiers to help. He also had to stop the Allies from sending their own troops. Louis also ordered Luxembourg to capture Liège, an important city.

Getting Ready for Battle

Luxembourg gathered a large army of 116,000 soldiers. He did this by taking soldiers from towns like Dunkirk and Ypres. On June 9, he started marching his troops. He made it seem like he might attack Liège, Huy, or Charleroi. This made the Allies divide their army to protect all three places.

However, Luxembourg didn't have enough soldiers to attack Liège and also keep the main Allied army busy. William III used this chance. He sent Lieutenant-General Ferdinand Willem of Wurttemberg with about 15,000 soldiers into a French area called Artois. Wurttemberg's job was to collect money from the people there. If they refused, he was ordered to burn their homes and farms. The people of Artois ended up paying a lot of money.

On July 18, Luxembourg ordered another general, Villeroy, to attack the small town of Huy. The Allies marched to help Huy, but the town surrendered on July 23 before they could get there. William then stopped and sent ten more groups of soldiers to Liège. This made the defense of Liège very strong.

William's remaining troops set up a line in a half-circle. It stretched from Eliksem on the right to Neerwinden on the left. This position allowed them to react quickly, but moving around was hard because the Little Geete River was behind them.

Luxembourg saw an opportunity. On July 28, he quickly changed his plans. After marching 30 kilometers, he arrived at the village of Landen in the evening. Luxembourg thought William would retreat and wait for Wurttemberg's soldiers to return. But William was told about the French approach by mid-afternoon. Even though he was advised to cross the river at night, he decided to stay and fight. He wanted Wurttemberg to finish his mission.

William's main reason for staying was that he didn't have enough horse soldiers for an organized retreat. Also, the ground he chose was good for causing heavy losses to the French cavalry. The French outnumbered him, with 66,000 soldiers to his 50,000. The battlefield was small, which meant Luxembourg couldn't fully use his larger army.

The Allied right side was key to their position. It protected their only way to retreat across the Geete River. They built strong defenses there, especially around the villages of Laar and Neerwinden. They put 80 of their 91 heavy cannons behind these defenses. In the middle, the open ground between Neerwinden and Neerlanden was heavily dug with trenches. The village of Rumsdorp was an advanced outpost. The left side, which was hard to attack, saw little action until the end of the battle.

Maximilian of Bavaria led the Allied right wing. Spanish dragoons (soldiers who rode horses but fought on foot) and Hanoverian foot soldiers were on the far right in Laar. English soldiers were between Laar and Neerwinden. Troops from Brandenburg were inside Neerwinden. Behind them, William placed 47 groups of cavalry (horse soldiers) in two lines. These were mostly from Hanover, Brandenburg, Bavaria, and Spain.

William himself led the center, which was mainly English and Scottish soldiers. Danish and Dutch soldiers were under Henry Casimir II in and around Neerlanden on the left side. Behind them were 59 groups of English and Dutch cavalry led by the Prince of Nassau-Usingen. Four groups of foot soldiers were sent to hold Rumsdorp.

Luxembourg focused his main attack force of 28,000 men on the Allied right side. His other commanders made smaller attacks on the Allied left and center. This was to stop the Allies from sending more soldiers to their right. These attacks involved three lines of cavalry, supported by two lines of foot soldiers, and three more lines of cavalry behind them. A strong force of foot soldiers and dragoons attacked Rumsdorp.

The Battle Begins

The cannon fight probably started between 6:00 and 7:00 in the morning. The Dutch army always had many cannons, and the Allied cannons were better than the French ones. So, the cannon fight went well for the Allies. They caused a lot of damage to the French. With about 150 cannons firing, the battle was very loud and intense. The Prince de Conti wrote that even the bravest officers had never seen such a long and close cannon fight. He said it was more like a sea battle than a land battle.

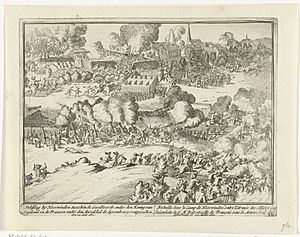

Between 8 and 9 a.m., the French began their attack on Laar and Neerwinden. Three groups of 28 battalions (large groups of soldiers) attacked fiercely. The Duke of Berwick led the attack on Neerwinden in the middle. Other generals supported his attack on his left and right. Laar was captured quickly. But things were harder for the French in Neerwinden. The French had to fight for every part of the village, and the defenders fought very bravely. Berwick gained ground slowly.

While this was happening, French cavalry, after taking Laar, crossed a small stream and attacked the Spanish cavalry. They defeated the Spanish. But then the French were pushed back across the stream and lost many soldiers. This attack, however, caused the English cannon operators behind Laar to leave their positions without being told to.

Berwick managed to get to the edge of Neerwinden. But the other French generals could not keep up with him. They faced heavy fire from the defenders and moved more towards the center of the village. Finally, they retreated behind Berwick. This proved to be a mistake for them. The Elector of Bavaria led a counterattack on the sides of the French generals' troops. This forced them out of the village. Then Berwick's troops were also pushed back, and Laar was recaptured. This important counterattack, helped by English soldiers sent by William III, brought the Allied lines back to their original positions. The French had lost many soldiers. One general was killed, and Berwick was captured.

Around the same time, the French also attacked Rumsdorp and Neerlanden. Rumsdorp was taken, but their attack on the trenches behind it was stopped. East of a small stream, dragoons (horse soldiers who fought on foot) attacked Neerlanden. They got in twice but were pushed back each time. The fighting here became very fierce, more than Luxembourg had planned. Both he and William rushed to this part of the battle. Luxembourg was unhappy and ordered his troops to fall back and just hold the outer fence of Rumsdorp. He then went back to his left side, where the tired troops from the Neerwinden attack were gathered. He reorganized them and added 12 new battalions from his reserve. He ordered a second attack on Laar and Neerwinden, this time led by the Prince de Conti.

This second attack was much like the first. Again, Laar was taken first. In Neerwinden, the defenders fought bravely from behind hedges, walls, and houses. They were very determined. But the Prince de Conti slowly pushed his way to the northern edge of the village. Here, the defenders held their ground with great effort. Again, William III rushed in with English soldiers and counterattacked. Most of Neerwinden was recaptured after a long and bloody fight, and then Laar was taken back too. The fighting was very intense in this small area. Many soldiers, about 30,000 to 40,000 men from both sides, fought closely, causing heavy losses for everyone.

It was almost midday, and Luxembourg was still far from his goal. His officers advised him to stop fighting. They pointed out that his troops were losing courage and his foot soldiers had suffered many losses. But Luxembourg decided to keep fighting. He still had 20 battalions of foot soldiers in reserve, including seven elite battalions from the French King's own guard. His cavalry (horse soldiers) of 30,000 men was also almost untouched.

Luxembourg took 7,000 foot soldiers from his center and left side for a third attack on the Allied right. He ordered all the foot soldiers to attack at once. He personally led the attack on Laar and Neerwinden. William again moved more English units to stop this threat. But this could not prevent the villages from finally falling to the French after very heavy fighting. The defenders were also running out of ammunition.

After this, de Feuquières ordered his cavalry to charge the weakened Allied center. The Irish Brigade was among them. They suffered severe losses, including the Irish hero Patrick Sarsfield. But the French broke through the Allied trenches, causing many casualties.

This French breakthrough happened around 3:00 p.m. An hour later, William ordered the Allies to retreat across the Geete River. As they retreated, they left behind most of their cannons. These cannons were dug into the ground and could not be moved in time. By then, there were many cavalry groups behind the Allied lines. The battle turned into a close-quarters fight with many horsemen clashing in a small area. William himself led several cavalry charges. This helped the right side of his army retreat across the Geete. They retreated in a messy way, but William and Maximilian managed to escape safely with many of their troops.

The Dano-Dutch left side, led by Henry Casimir, retreated better. They faced strong resistance. During their retreat, his troops fought enemy foot soldiers and most of the French cavalry. They were surrounded from all sides. However, they managed to fight their way through the French for about 7 kilometers. They crossed the Geete River in good order. Nine more battalions of Dutch and Danish foot soldiers, led by Count Solms and Brigadier François Nicolas Fagel, also fought bravely to protect the retreat. They were helped by some British units holding positions around the bridge. Solms was badly wounded and later died. A few hundred Allied horsemen drowned trying to cross the Geete. But by 5:00 p.m., most of the army had reached the other side of the river. They continued their retreat without being bothered by the French cavalry.

What Happened After

Usually, French generals would announce their victories with many details and praise. But this time, Luxembourg only sent a short message to the king. The Battle of Landen could have been a huge victory if the French attacks on the Allied left and center had gone as planned. As it was, both sides lost many soldiers. However, the numbers of dead and wounded varied a lot in different reports.

The French themselves said they lost between 7,000 and 8,000 men. A Dutch newspaper editor disagreed. He said it was "a regular habit" for the French to change the numbers, but this time they had really exaggerated. A French officer also said they lost 18,000 to 20,000 men. He wrote that the French won, but they paid a very high price. He said they lost many officers and soldiers. He also mentioned that the enemy called it the "Battle of the Fascines" because of the many French dead used to fill ditches. Estimates for Allied losses range from 8,000 to 18,000 killed and wounded. Another 1,500 or 2,000 were captured, mostly Dutch soldiers cut off in Rumsdorp. A visitor to the area in 1707 noted that the fields were still covered with bones.

William had a silver medal made to celebrate his success in "saving Liege" and escaping with most of his troops. This was partly to counter the news of the Battle of Lagos on June 27. In that battle, the French attacked a large English and Dutch trade convoy, causing serious financial damage. But William's claim was also true. Luxembourg's foot soldiers were so tired and damaged that he could not attack Liège. The Dutch were able to replace their losses within days.

A mutiny (rebellion) even broke out in the French army. Whole regiments rioted and demanded their unpaid wages. King Louis XIV sent money and ordered Luxembourg to return to the French border. This was to reassure the troops that they would not have to fight another battle right away. Because of these reasons, the battle has also been called a Pyrrhic victory. This means a victory that costs so much that it feels like a defeat.

William was able to save Liège and Maastricht from attack. Also, the Duke of Württemburg's raid in French Flanders was successful. This meant that the 1693 campaign could be seen as an overall success for the Allies. Still, losing Namur in 1692 and then the defeat at Landen showed William and Anthonie Heinsius, the Dutch leader, that the Allies had too few soldiers. This made it hard to protect the Spanish Netherlands well. As a result, the English and Dutch armies grew much bigger in the following years. This allowed William and the Allied army to go on the attack for the next three years.

Luxembourg has been criticized for not using his victory better. However, his troops were exhausted. Also, the bad harvests meant there wasn't enough food for the horses and supply wagons needed to chase his enemies. This problem was so bad that capturing the Allied cannons was actually difficult. The French barely had enough supplies to move their own cannons. The French attacks stopped, although Charleroi was captured in October. Landen was Luxembourg's last battle. He died in January 1695, and King Louis XIV lost his best general.

Legacy

Laurence Sterne's famous 1759 novel, Tristram Shandy, mentions the Nine Years' War. Most of the references are about the 1695 Second Siege of Namur. However, a character named Corporal Trim talks about the Battle of Landen:

Your honour remembers with concern, said the corporal, the total rout and confusion of our camp and army at the affair of Landen; every one was left to shift for himself; and if it had not been for the regiments of Wyndham, Lumley, and Galway, which covered the retreat over the bridge Neerspeeken, the king himself could scarce have gained it – he was press'd hard, as your honour knows, on every side of him...

During this battle, the French were very determined to gain the high ground, even with heavy Allied cannon fire. William is said to have exclaimed, "Oh! That insolent nation!"

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Landen para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Landen para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |