Blakeney Chapel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Blakeney Chapel |

|

|---|---|

No structures are now visible above ground at the site.

|

|

| General information | |

| Town or city | Cley next the Sea, Norfolk |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 52°57′56″N 1°02′31″E / 52.9656°N 1.0420°E |

| Designations | |

Blakeney Chapel is an old, ruined building on the coast of North Norfolk, England. Even though it's called a 'chapel,' it probably wasn't a church. It's also not in the village of Blakeney, but actually in a nearby area called Cley next the Sea.

This building stood on a small, raised area of land, like a tiny island, in the coastal marshes. It was less than 200 meters (about 220 yards) from the sea. It was also just north of the River Glaven, where the river turns to flow along the coastline.

The building had two rectangular rooms of different sizes. A map from 1586 shows it looking complete. However, later maps show it as ruins. Today, only the foundations and a small part of a wall remain.

Between 1998 and 2005, archaeologists studied the site three times. They learned more about how it was built and found signs of two different times when people actively used the building. Even though some maps call it a chapel, there is no proof that it was ever used for religious purposes. The only sign of a specific activity found was a small fireplace, likely used for melting iron.

Much of the building material was taken long ago. People reused it to build other structures in Cley and Blakeney villages. The remaining ruins are protected because they are historically important. They are a scheduled monument and a Grade II listed building. However, no one is actively managing the site. The sea is slowly moving closer, and this threat is growing. The river's path was changed, which means the ruins are now more exposed. They might eventually be lost to the sea.

Contents

What is Blakeney Chapel?

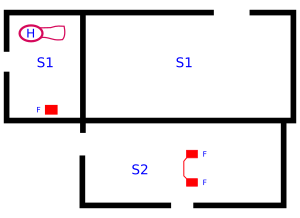

The Blakeney Chapel ruins are made up of two main parts. The larger part (called S1) is a rectangle, about 18 meters (59 feet) long and 7 meters (23 feet) wide. A smaller rectangular building (S2) is attached to the south side of the main room. It is about 13 meters (43 feet) long and 5 meters (16 feet) wide.

Most of the building is buried underground. Before the 2004–05 dig, only a 6-meter (20-foot) long wall made of flint and mortar was visible. It stood about 0.3 meters (1 foot) high. The ruins are on the highest point of Blakeney Eye, about 2 meters (7 feet) above sea level.

Blakeney Eye is a sandy mound in the marshes. It is located inside the sea wall. This is where the River Glaven turns west towards a safe harbor called Blakeney Haven. Cley Eye is a similar raised area on the east side of the river. Even though it's called Blakeney Eye, this area is actually part of the parish of Cley next the Sea.

The land where the building stands belonged to the Calthorpe family for a long time. In 1912, a banker named Charles Rothschild bought it. Rothschild then gave the property to the National Trust. They have managed the site ever since. People cannot visit the site.

The ruins are protected as a scheduled monument and a Grade II listed building. This is because they are historically important. These protections do not cover the land around the ruins. However, the entire marsh is part of the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). This area is important for its wildlife. The SSSI is also protected by other international agreements. It is part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB).

History of the Building

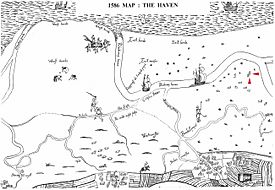

The building first appeared on a map in 1586. This map showed the Blakeney and Cley area. It was likely made for a legal case about who owned "wreck and salvage" (things found from shipwrecks). We don't know the result of that case. The original map was lost in the 1800s, but copies still exist.

On this 1586 map, the building on the Eye looks complete with a roof. But it doesn't have a name. A map from 1769 by the Cranefields calls the building "Eye House." However, by 1797, mapmaker William Faden's map of Norfolk shows "chapel ruins." This description was then used consistently from the 1800s onwards. Some maps, including Faden's, show another ruined chapel across the Glaven on Cley Eye. But there are no other records about that building.

The medieval churches of St Nicholas, Blakeney and St Margaret's, Cley, and the ruined Blakeney friary, were not the first religious buildings here. An early church was mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book. It was in Esnuterle, an old name for Blakeney. The current name, Blakeney, first appeared in 1340. The location of this 11th-century church is unknown. There is no reason to think it was on the 'chapel' site.

A booklet about Blakeney from 1929 said there was a "chapel of ease" in the marshes. It claimed a friar from the Convent served it. But the document it refers to, from 1343, only says a local hermit could ask for alms (donations) in "divers parts of the realms." There is no proof that any religious building was dedicated on the marshes. Also, no medieval documents mention a chapel there.

Archaeological Investigations

The first study of the chapel ruins happened in 1998–99. A local history group, supported by the National Trust, carried it out. They had a license that allowed them to access the site but not to dig. So, they used height measurements, geophysics (like checking electrical resistance and magnetism), and samples from molehills. They surveyed an area 100 meters (109 yards) long and 40 meters (44 yards) wide.

The magnetic survey did not find the buried parts of the chapel. But it did show an unexpected straight line, which was from buried iron from wartime defenses. The resistance survey clearly showed the larger room. However, it barely detected the smaller one. This suggests the smaller room had weaker foundations and was probably not as well-built. It might also have been built later.

Plans to change the Glaven river channel meant the Eye would no longer be protected from the sea. It would eventually be destroyed by coastal changes. So, it was decided to study the site while it still existed. A first look was done in 2003. This prepared for a full survey in 2004–05. The surveyed area covered 10 hectares (25 acres). This was much larger than the 0.4 hectares (1 acre) of the 1998 study.

Archaeologists dug 50 trenches outside the buildings. Each trench was 50 meters (164 feet) long and 1.8 meters (6 feet) wide. They also dug six trenches of different sizes inside the chapel. The total area of these trenches was equal to two of the standard ones. They also drilled eight boreholes to study the ground. They used geophysics and metal detection to find things buried underground.

The main excavation happened in the winter of 2004–05. It focused on the building and the area 10 meters (33 feet) around it. The results showed that people lived there at different times. After the dig, the remains of the building were reburied. So, nothing is visible on the surface today.

Archaeological Discoveries

Early Life at the Site

The oldest signs of people living here are ditches from the 11th or 12th century. These ditches likely formed an enclosed area. The southeast corner of this area is under the 'chapel.' Any signs of buildings within this enclosure have either been lost to the river or are buried outside the surveyed area.

Few items were found with the ditches. Some pieces of Roman or older pottery were found nearby. Also, three Henry III pennies were discovered. As with other finds on the site, it's hard to know if the old pottery was used where it was found. By the time the main building was constructed, around the 14th century, the ditches had filled with sand.

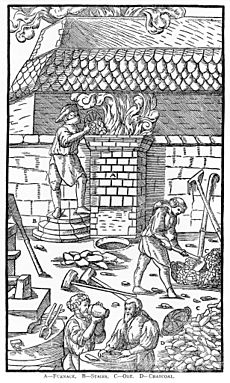

A small fireplace was built at ground level. This happened just before or during the building of S1. It seems it was not used very much. But the presence of slag (waste from metalwork) suggests it was used for smelting iron. Perhaps a smith worked there. There were signs of other small fires in S1 around the same time. It's unknown if they were related to the iron smelting. Back then, fireplaces couldn't melt iron completely. They produced a 'bloom,' which was a mix of iron and slag. This bloom could be turned into wrought iron by heating and hammering it many times. Another, even older, smelting fireplace was found at West Runton, about 17 kilometers (11 miles) east on the Norfolk coast. The main ore (rock with metal in it) in this area is iron-rich local carrstone.

Medieval Period

The larger north building (S1) was built without deep foundation trenches. But it was still a strong, well-made building of flint and mortar. The main archaeologist believed "substantial time and money" were spent on it. The flints used got smaller as the walls went up. The inside corners were decorated with limestone blocks called quoins. Seashells were found, suggesting they were part of the building's structure. They were used as galleting (strengthening for the mortar).

There were entrances in the west and northeast walls. There is also some evidence that windows were once in the northwest and south walls. The floor was packed earth. We don't know what the original roof was made of. However, a few glazed floor tiles and Flemish pantiles from a later time suggest it looked quite fancy. There was no inside wall at this time. There might have been a wooden extension on the southwest corner outside.

The medieval building was eventually left empty. Much of its material was taken to be reused in Blakeney and Cley villages. A stone archway in Cley is traditionally thought to have come from the chapel. It would fit the western entrance. However, it could have come from somewhere else, like the ruined Blakeney friary. The 'chapel' building was abandoned around 1600. We don't know if the collapse of its east end caused its disuse or happened because it was no longer used. The main building seems to have had a big fire at some point. No wooden parts have been found. The site was flooded at least three times after the building collapsed. At some point, part of the western wall was lost. The steep slope where it stood suggests the sea might have taken it.

Most of the pottery found in the larger room was from the 14th to 16th centuries. Nearly a third of this pottery came from other countries. This shows how important the Glaven ports were for international trade back then. The pottery seemed to be mostly for everyday use, like jugs and cooking pots.

Later Use (Post-Medieval)

The 17th-century room, S2, used the south wall of the older building as its own north wall. It was mostly built using materials saved from S1. However, the quality of the work was not as good. The new room had a double fireplace. But there was no sign of a wall dividing the two hearths. Limestone blocks, just like the decorative ones in S1, were used in the fireplace. Besides the pantiles from S1, there were also Cornish slate roof tiles. It's not clear if these were part of the S2 roof or linked to the possible wooden extension.

At the same time S2 was built, a dividing wall was added across S1. This wall was also not very well made. It created a western room. There were no molehills inside this smaller building. This suggested it had a solid floor, unlike its neighbor. Digging confirmed this. The floor was originally made of mortar and was relaid at least once. Then, it was covered with a layer of flint cobbles. This suggests it was a working area. The old fireplace was not covered, so it might still have been used. A new fireplace was also added. It looked like a home fireplace, but its location makes that use unlikely.

A clear path led southwest down the slope from S1. A large midden (a pile of waste) was near the path. It has been suggested that a "clean" pit north of S1 was a well. Fresh water would float above the saltwater below. This happens at Blakeney Point and other places on the Norfolk coast.

There is only limited proof of use after the 17th century. This includes a 19th-century tobacco pipe and some Victorian glass. A barbed wire fence from wartime ran through the ruins. It was found during digging and by magnetic surveys. Other modern finds included a gin trap, bullets, and other small metal objects.

What Was Its Purpose?

Blakeney Eye has a long history of people living there. Many items from the Neolithic (New Stone Age) have been found. But few items from Roman or Anglo-Saxon times were discovered. However, a gold bracteate (a thin metal disc) was a rare and important find from the 6th century.

Animal and plant remains showed that people ate both farm animals, like goats, and local wild animals, like curlews. Rabbit and dog remains might mean people used fur from these animals. Evidence of cereal (grain) processing and storage is hard to date. But it might be from the medieval period.

The buildings were abandoned during the 17th century. Their uses, which might have changed over time, are still unknown. The east–west direction and good quality of S1 would not stop it from being a religious building. But there is no other proof, from digs or old papers, to support that idea. The small number of items found, even things that couldn't be reused, suggests that few people lived there for a short time during the medieval period. Other possible uses have been suggested, like a custom house (where taxes on goods were collected) or a warrener's house (for someone who managed rabbits). But again, there is no proof for these ideas.

Threats to the Chapel

The River Glaven has been moved. This means the ruins are now north of the river bank. They are basically unprotected from the sea. The moving shingle (small stones) will no longer be washed away by the river. The chapel will be buried by a ridge of shingle as the spit continues to move south. Then, it will be lost to the sea. This might happen within 20–30 years (by 2035).

The ridge of shingle runs west from Weybourne along the Norfolk coast. Then it becomes a spit that extends into the sea at Blakeney. Saltmarshes can grow behind this ridge. But the sea attacks the spit with tides and storms. The amount of shingle moved by one storm can be "spectacular." The spit has sometimes been broken through, becoming an island for a while. This might happen again. The northernmost part of Snitterley village was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.

Over the last two hundred years, maps have been accurate enough to measure the distance from the ruins to the sea. In 1817, it was 400 meters (437 yards). By 1835, it was 320 meters (350 yards). In 1907, it was 275 meters (301 yards). By the end of the 20th century, it was 195 meters (213 yards). The spit is moving towards the mainland at about 1 meter (1 yard) per year. Several raised islands, or "eyes," have already been lost to the sea as the beach has rolled over the saltmarsh.

The shingle moving inland meant the Glaven river channel was getting blocked more often. This channel was dug in 1922 because an older, more northerly path was overwhelmed between Blakeney and Cley. The blocking led to flooding in Cley village and the important freshwater marshes. The Environment Agency looked at different solutions. Trying to stop the shingle or breaking through the spit to create a new river outlet would be expensive and likely not work. Doing nothing would harm the environment. The Agency decided to create a new path for the river south of its original line. Work to move a 550-meter (601-yard) stretch of river 200 meters (219 yards) further south was finished in 2007. It cost about £1.5 million.

Managed retreat is likely the long-term plan for rising sea levels along much of the North Norfolk coast. It has already been used at other important sites like Titchwell Marsh.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |