North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Norfolk Coast SSSI |

|

|---|---|

Salt marsh near Brancaster Staithe

|

|

North Norfolk Coast SSSI shown within Norfolk

|

|

| Location | Norfolk, East of England, England |

| Established | 1986 |

The North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is a very important area for nature in Norfolk, England. It covers a huge 7,700 hectares (about 19,000 acres) of the north coast. This special place stretches from Holme-next-the-Sea to Kelling. It has extra protection as a Special Protection Area (SPA) and is on the Ramsar list for wetlands. It's also part of the beautiful Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Most of it is even a Biosphere Reserve, which means it's recognized globally for its unique environment.

This SSSI is home to many different habitats. You can find reed beds, salt marshes, freshwater lagoons, and sandy or shingle beaches. These wetlands are super important for wildlife. Rare birds like pied avocets, western marsh harriers, Eurasian bitterns, and bearded reedlings breed here. It's also a popular stop for migrating birds, including some very rare ones that get lost. Many ducks and geese spend the winter along this coast. Several nature reserves here protect water voles, natterjack toads, and many unusual plants and invertebrates (like insects and worms).

The area also has a rich history, with amazing finds from the Upper Paleolithic period (Stone Age). You can see an Iron Age fort mound at Holkham. There's also the site of a large Roman naval port and fort near Brancaster. Remains from both World Wars are here too. These include old gun ranges, hospitals, bombing ranges, and defensive structures like pillboxes and tank traps.

The SSSI is important for the local economy because it attracts many tourists. People come for birdwatching and other outdoor activities. However, sensitive wildlife areas are carefully managed to protect them from too many visitors. Another big challenge is the sea slowly taking over the soft coastline. Experts think that allowing the sea to move inland naturally (called "managed retreat") might be the best long-term plan. They are working to create new nature reserves further inland to replace lost habitats.

Contents

Discovering the North Norfolk Coast SSSI

The SSSI is a long, thin strip of coastline. It starts near Old Hunstanton and stretches east for about 43 kilometers (27 miles) to Kelling. The southern edge generally follows the A149 coast road, avoiding towns and villages.

Diverse Habitats Along the Coast

The SSSI has many different types of natural environments.

- Mud, Sand, and Shingle: The areas between high and low tide are mostly bare mud, sand, and shingle. Some higher spots might have algae or eelgrass, which ducks and geese eat in winter.

- Salt Marshes: These form in calm, sheltered areas. The SSSI has some of the best salt marshes in Europe. They are home to a huge variety of plants.

- Sand Dunes: You can find sand dunes in several places. The best ones are at Holme Dunes, Holkham, Blakeney Point, and Scolt Head Island.

- Shingle Ridges: Blakeney Point and Scolt Head Island are also important for studying how shingle ridges form.

- Reed Beds: These are found in specific spots, with large areas at Titchwell Marsh, Brancaster, and Cley Marshes.

- Grassland: Some areas are grasslands that used to be salt marshes. These are wetter at Cley and Salthouse marshes.

- Woodland: There isn't much woodland in the SSSI. However, a group of Corsican pine trees at Holkham helps other trees and shrubs grow.

A Journey Through Time: History of the Coast

Norfolk has been home to people for a very long time, going back to the Paleolithic (Stone Age).

Ancient Times: From Stone Age to Vikings

Both modern humans and Neanderthals lived here between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago. This was before the last Ice Age. Humans returned as the ice melted and moved north. Not many ancient finds exist from 20,000 years ago. This is partly because it was very cold, and the coastline was much further north. As the ice retreated during the Mesolithic period (10,000–5,000 BCE), the sea level rose. This created the North Sea and brought the Norfolk coastline closer to where it is today. Many ancient sites are now under the sea.

Early Mesolithic flint tools, up to 15 cm (6 inches) long, were found at Titchwell. These tools date from a time when the coast was 60–70 km (37–43 miles) from the sea. Other flint tools have been found from the Upper Paleolithic (50,000–10,000 BCE) to the Neolithic (5,000–2,500 BCE).

By 11,000 BC, the people who made the long flint blades were gone. Two wooden platforms found at Titchwell might be rare Bronze Age (2,500–800 BCE) structures. Seahenge is another early Bronze Age site found at Holme in 1998. It's a ring of 55 oak posts built in 2049 BC. A similar structure, Holme II, might be even older. A large Iron Age fort at Holkham covered 2.5 hectares (6.1 acres). It was at the end of a sandy spit in what was then salt marsh. This fort was used until the Iceni people were defeated in 47 AD.

Roman period settlements have been found all along the Norfolk Coast. A notable site is Branodunum, near Brancaster, which covered at least 23 hectares (57 acres). This site included a fort built like a Roman camp (a castrum). It had walls 2.9 meters (10 feet) wide and internal towers. Early Saxon sites are rare near the coast. However, a gold ornament found near Blakeney Chapel was a rare 6th-century discovery. There is also a later Saxon cemetery at Thornham. The Danelaw (Viking rule) left few physical traces. But place names like Holkham ("ship town") show the Viking influence.

From Medieval Times to the 1800s

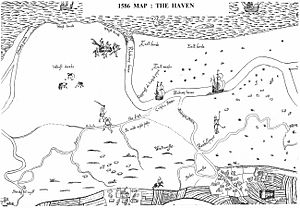

An "eye" is a higher area in the marshes that is dry enough for buildings. Cley Eye had been farmed since ancient times. It was 28 hectares (70 acres) in 1651, but coastal erosion has made it much smaller. The Eye and its Saxon barn were reached by an old causeway that could be crossed at low tide. A 1588 map showed "Black Joy Forte" in the same area. This fort might have been planned to defend against the Spanish Armada, but it was never finished.

On the other side of the Glaven River, Blakeney Eye had a fenced area in the 11th and 12th centuries. A building called "Blakeney Chapel" was used from the 14th century to around 1600, and again in the late 17th century. Despite its name, it was probably not a religious building. Nearly a third of the pottery found there was imported from other countries. This shows how important the Glaven ports were for international trade back then.

The calm waters of Blakeney Haven brought wealth to the Glaven ports of Cley, Wiveton, and Blakeney. Blakeney got its market charter in 1222. In 1322, these three ports, along with Salthouse, had to provide three ships for King Edward II. By the early 15th century, Blakeney was one of the few ports allowed to trade in horses, gold, and silver. This helped the town become even richer.

In 1640, projects to reclaim land from the sea, especially by Henry Calthorpe near Cley, caused the shipping channel to fill with silt. This forced the wharf to move. More land reclamation east of the Glaven meant all the Glaven ports declined. Cley and Wiveton became too shallow in the 17th century. Blakeney continued to have packet ships (ships carrying mail and passengers) until 1840. Similar land reclamation happened elsewhere, often with the same result for local harbors. Only Wells-next-the-Sea had significant trade into the late 20th century.

Coastal Defences in the 20th Century

There might have been cannons at Gun Hill near Burnham Overy during the Napoleonic Wars. However, there were no modern forts in north Norfolk at the start of World War I. After a German naval attack in November 1914, defences were built along the Norfolk coast. These included trenches, concrete pillboxes, and gun batteries. While the main military bases were outside the SSSI, Thornham Marsh was used as a bombing range by the Royal Flying Corps from 1914 to 1918. An old concrete building on Titchwell's west bank was a holiday home until the British Army used it in 1942. Some brick remains at Titchwell Marsh are all that's left of a military hospital from that time.

No new forts were built on this coast at the start of World War II. But after France fell in 1940, the threat of invasion led to new defences. Anti-tank obstacles and fourteen coastal batteries (each with two guns) were built. Some of these military sites were within the SSSI. The marsh at Titchwell was flooded again, and pillboxes were built into the beach bank. From 1942 to 1945, the marsh was used by the Royal Tank Regiment. They set up a gunnery range for armoured vehicles, with targets every 900 meters (980 yards). Some islands were built to hold "pop-up" targets, controlled by cables from a building whose foundations are now under a bird hide. Remains of the triangular concrete track used by the tanks can still be seen.

Military activities continued after the war. The Royal Air Force returned to Thornham Marsh from 1950 to 1959. Bombing practice was watched from a control tower, which was taken down in 1962. Only a concrete structure remains. The wrecks of two World War II Covenanter tanks, likely used as targets, sometimes appear at low tide. The SS Vina, an old cargo ship, was anchored offshore in 1944 as an RAF target. But a storm dragged her to the sands off Titchwell, where her wreck can still be seen at low tide.

Brancaster beach had a base with three pillboxes, Nissen huts, and two gun positions. Another possible base with about fifty structures was in a salt marsh near Burnham Overy Staithe. A wreck at Scolt Head Island was used as a bombing target. Remains of a Blenheim bomber were found there in 2004.

Royal Artillery forts were built at Cley beach. These included two large guns, five buildings, two pillboxes, a minefield, and concrete anti-tank blocks. A spigot mortar and an Allan Williams Turret (machine gun position) were closer to the village. One pillbox and parts of the gun positions were still there in 2012. The military camp housed 160 men and later held prisoners of war. Near the end of the war, the camp housed refugees from Eastern Europe. It was finally taken down in 1948. Many wartime buildings were destroyed in 1955. However, the generator house was used by the coastguard as an observation post. The Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) bought it in 1983. The top part was a lookout, and the bottom became a beach café. A storm in 2008 covered the building with shingle, and it was later demolished.

Protecting the Coast: Conservation Efforts

The first step to protect this coast was in 1912. Banker Charles Rothschild bought Blakeney Point and gave it to the National Trust. They have managed it ever since. In 1926, another protected area was created. Norfolk birdwatcher Dr. Sydney Long bought the land for the Cley Marshes reserve for £5,100. He wanted it to be "a bird breeding sanctuary forever." Long then started the Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT).

The current SSSI was created in 1986. It combined older SSSIs like Blakeney Point, Holme Dunes, Cley, and Salthouse Marshes (all from 1954). It also included national nature reserves (NNRs) at Scolt Head Island (1967) and Holkham (1968). Many areas that weren't protected before were also added.

While much of the SSSI is privately owned, large parts are managed by conservation groups. Besides the two NNRs, there's an RSPB reserve at Titchwell Marsh. The NWT manages reserves at Cley and Salthouse Marshes, and also the Holme Dunes NNR. The National Trust owns land at Brancaster Staithe and Blakeney Point.

The SSSI covers 7,700 hectares (19,027 acres). It has extra protection from Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA), and Ramsar listings. It's also part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Scolt Head Island and the coast from Holkham NNR to Salthouse are a Biosphere Reserve.

Amazing Animals and Plants

Birds: Feathered Friends of the Coast

The SSSI is a Special Protection Area because of its many coastal habitats for birds. Large groups of Sandwich terns and little terns breed here, especially at Blakeney Point and Scolt Head Island. These are important for Europe. The coast also has important numbers of common terns, pied avocets, and reedbed birds. These include western marsh harriers, Eurasian bitterns, and bearded reedlings. Other birds nesting in the wetlands are the northern lapwing, common redshank, and different kinds of warblers. Ringed plovers and Eurasian oystercatchers lay eggs on the bare sand dunes. Little egrets, Eurasian spoonbills, and black-tailed godwits are here most of the year. The egret and spoonbill have even started nesting in the SSSI.

In spring and early summer, migrant birds like the little gull and black tern might pass through. They are on their way to breed elsewhere. In autumn, birds arrive from the north. Some, like whimbrels, just stop for a few days to rest before flying south. Others stay for the winter. Out at sea, great and Arctic skuas, northern gannets, and black-legged kittiwakes might fly close by. Many ducks spend the winter along the coast. These include Eurasian wigeons, Eurasian teals, mallards, and gadwalls. Red-throated divers are usually on the sea. Brent geese eat sea lettuce and other green algae. Barn owls and sometimes hen harriers hunt over the marshes in winter. Flocks of snow buntings can be found on the beaches. Thousands of geese, mostly pink-footed, rest at Holkham.

The SSSI's location on the north-facing east coast is great for migrating birds when the weather is right. This can include very rare birds that have wandered off course. A black-winged stilt, nicknamed "Sammy," arrived at Titchwell in 1993 and stayed until 2005. Other rare visitors included a western sandpiper at Cley in 2012 and a rufous-tailed robin at Warham Greens in 2011.

Other Animals: From Toads to Tiger Beetles

Water voles are a very endangered animal in the UK. Their numbers have dropped a lot, mainly because of American mink (an animal that hunts them). But habitat loss and water pollution also play a part. Important places for water voles in East Anglia include Cley, Titchwell, and other Norfolk coastal sites. Brown hares are common. You might also see European otters in several spots. Both common and grey seals can be seen at the Blakeney Point colony and off the beaches.

The common frog, common toad, and common lizard all live in suitable habitats. The rare natterjack toad breeds at Holkham and Holme.

Butterflies like the green hairstreak and purple hairstreak are sometimes seen. You might also spot the hummingbird hawk-moth and ghost moth, especially in the woods at Holkham. In some years, many clouded yellow or diamondback moths appear. The dune tiger beetle is a nationally rare insect found in damp sand dunes.

The lagoons behind the shingle beach at Salthouse and Cley are salty. This is because seawater seeps through the bank. These salty lagoons are home to some rare and endangered invertebrates. These include the starlet sea anemone, lagoon sand shrimp, Atlantic ditch shrimp, and lagoon cockle. These marshes are the only reliable place in the UK to find the water beetle yellow pogonus.

Plants: Coastal Flora

On exposed parts of the coast, strong tides wash away mud and sand. So, there's no vegetation except for some algae or eelgrass. Where the shoreline is more protected, important salt marshes can form. These have several uncommon plant species. The most exposed parts of the salt marshes have glassworts and common cord grass. As the marsh becomes more established, other plants grow. First comes sea aster, then mainly sea lavender. You'll find sea purslane in the creeks. Smaller areas have sea plantain and other common marsh plants. The rare spiral tasselweed and long-bracted sedge are also found in the lower salt marsh.

Scrubby sea-blite and matted sea lavender are common in the drier upper salt marsh. They are uncommon in the UK away from this coast. You might see them with rare species like lesser centaury and sea pearlwort. Soft hornwort grows in the ditches.

Grasses like sea couch grass and sea poa grass are important in the driest parts of the marshes. On the coastal dunes, marram grass, sand couch-grass, and lyme-grass help hold the sand together. Sea holly and sand sedge are other special plants of this dry habitat. Petalwort is a nationally rare moss found on damper dunes. Bird's-foot trefoil, pyramidal orchid, and bee orchid flower on the dunes. Holkham's Corsican pines protect creeping lady's tresses and yellow bird's nest orchids. The shingle ridges on Scolt Head Island and from Blakeney Point to Salthouse attract plants like biting stonecrop, sea campion, and yellow horned poppy. Sea barley is a rarer plant in this habitat.

The reedbeds, largest at Cley, Salthouse, and Titchwell reserves, are mostly common reed. Other wetland plants include salt marsh rush and common bulrush. The coastal pastures at Cley and Salthouse Marshes have jointleaf rush and common silverweed. They also have less common grasses like annual beard grass. The flat land inland from the dunes at Holkham was reclaimed from the marshes. It was used for grazing, then for farming during World War II. Now, water levels are raised to attract breeding and wintering birds. These pastures are very important for the thousands of geese and ducks that feed there in winter.

Visiting the North Norfolk Coast

You can reach Scolt Head Island by a ferry from Burnham Overy Staithe from April to September. Boats from Morston quay can also take you to Blakeney Point. You can see the seal colonies or avoid the long walk along the shingle spit from Cley Beach. The National Trust has an information center and tea room at the quay. A visitor center on the Point, which used to be a lifeboat station, is open in the summer.

Most of the SSSI is close to the A149 coast road. You can get to it from many places using footpaths or roads. The main places for nature lovers are at the big reserves. Holme Dunes NNR is reached from Holme-next-the-Sea. It has a visitor center, three bird hides (one with disabled access), and a 4 km (2.5 mile) nature trail.

The other reserves are all next to the A149. Titchwell Marsh RSPB is just west of Titchwell village. It has a visitor center, café, and hides. Most of the reserve is wheelchair accessible. However, the last part of the path to the beach is rough and goes over a steep bank. The two bird hides at Holkham NNR can be reached from Lady Anne's Drive in Holkham village. There's also a car park further east on Beach Road, Wells-next-the-Sea. Cley Marshes visitor center and car park are south of the A149, across from the main reserve. The center and four of the five bird hides are accessible for people with limited mobility.

Because they are near the main coast road, you can reach the reserves by bus as well as car. The Peddars Way National Trail runs along the entire SSSI. Only short parts of this long walking path go south of the SSSI boundary.

Fun Activities and Local Economy

A survey in 2005 found that 39% of visitors to six North Norfolk coastal sites came mainly for birdwatching. In 1999, about 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million overnight visitors came to the area. They spent an estimated £122 million, which created about 2,325 full-time jobs. Titchwell Marsh RSPB, Cley Marshes NWT, and Holkham NNR each attract 100,000 or more visitors every year.

The small village of Titchwell shows how much wildlife visitors can help the local area. It's next to Titchwell Marsh, the RSPB's busiest reserve. A 2002 survey said that about 137,700 visitors spent £1.8 million in the area in 1998. The village has two three-star hotels and a shop selling telescopes and binoculars. However, it doesn't have a general store or a public house.

Sometimes, the large number of visitors can cause problems. Wildlife can be disturbed, especially species that breed in open areas like ringed plovers and little terns. Wintering geese can also be affected. Plants can get trampled, which is a big issue in sensitive places like sand dunes. To reduce damage, wardens protect breeding colonies. Fences, boardwalks, and signs help control where people go. Car parks are also placed carefully.

The Norfolk Coast Partnership, a group of conservation organizations, divides the coast into zones for tourism. Holme dunes, Holkham dunes, and Blakeney Point are sensitive habitats that get a lot of visitors. They are "red-zone" areas, meaning no new development or parking improvements are suggested. "Orange" locations have fragile habitats but fewer tourists, or they are large nature reserves ready for many visitors. The strongest sites, mostly outside the SSSI, are in the "green zone."

Challenges Facing the Coast

The North Norfolk coast is made of soft Quaternary glacial material, which lies over Cretaceous chalk. The chalk is visible at Hunstanton cliffs, just west of the SSSI. Unlike the fast-eroding cliffs further east, this SSSI coast has changed less consistently. Between 1880 and 1950, more beach material was added than lost. However, this coastline is threatened by climate change. Sea levels have been rising by about 1–2 mm per year for the last 100 years. This increases the risk of flooding and coastal erosion.

One of the most vulnerable parts is between Blakeney Point and Weybourne. This includes the Cley and Salthouse Marsh reserves. A shingle ridge protects the coast here. But the sea attacks the ridge and spit with tides and storms. A single storm can move a huge amount of shingle. The Blakeney Point spit has sometimes been broken, becoming an island for a while. This might happen again. The northern part of nearby Blakeney was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.

The spit is moving towards the mainland by about 1 meter (1 yard) per year. Maps from the last two hundred years show how much the sea has moved inland. Blakeney Chapel was 400 meters (440 yards) from the sea in 1817. By the end of the 20th century, this had shrunk to 195 meters (215 yards). The shingle moving inland means the River Glaven's channel gets blocked more often. This leads to flooding in the reserve and Cley village. The Environment Agency looked at ways to protect these areas. A new route for the river, south of its original line, was finished in 2007. It cost about £1.5 million.

The Environment Agency's long-term plan is to only protect communities and important buildings. Elsewhere, they plan for "managed retreat" as the sea level rises. This means allowing the sea to move inland naturally. This even applies to sites like Cley, where the money from tourism is more than the cost of keeping up sea defenses. A plan to allow tidal flooding in part of the reserve has already been put into action at Titchwell Marsh.

Another strategy is to create new reserves further inland. To make up for the reedbeds that will be lost at Cley, the Environment Agency and the Norfolk Wildlife Trust have been working since 2010. They are creating a new wetland near Hilgay. The 60-hectare (150-acre) Hilgay Wetland Creation Project is turning old farmland into different wetland habitats. They use banks, ditches, and a lake to control water levels. The Trust sees this as the first step in a long-term plan to create a roughly 10,000-hectare (25,000-acre) Wissey Living Landscape.

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |