Blakeney Point facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Blakeney Point |

|

|---|---|

The visitor centre, formerly a lifeboat station

|

|

| Location | North Norfolk, Norfolk, England |

| Operator | National Trust |

| Website | National Trust Blakeney Point |

Blakeney Point is a special place for nature found on the north coast of Norfolk, England. It's close to the villages of Blakeney, Morston, and Cley next the Sea. The main part of Blakeney Point is a long strip of land, about 6.4 km (4 mi) long, made of shingle (small, smooth stones) and sand dunes.

This amazing area also includes salt marshes (grassy areas flooded by tides), muddy flats, and old farmland. The National Trust has looked after Blakeney Point since 1912. It's part of many important protected areas, like a National Nature Reserve and a Special Protection Area for birds. Scientists have been studying Blakeney Point for over 100 years. They've learned a lot about its plants and animals.

People have lived in this area for a very long time. There are even old ruins of a medieval monastery hidden in the marshes. The towns nearby were once busy harbours, but changes to the land caused the river channels to fill with mud. Today, Blakeney Point is super important for birds that come to nest, especially terns. It's also a major stop for migrating birds in autumn. You can often see hundreds of seals resting at the end of the spit. The sand and shingle are home to unique insects and plants, like the tasty samphire, also called "sea asparagus."

Many visitors come to Blakeney Point to watch birds, sail, or just enjoy nature. This helps the local economy. However, too many people can disturb nesting birds and damage the fragile dunes. To protect the wildlife, some areas are restricted for people and dogs. Boat trips are a great way to see the seals without bothering them. The spit itself is always changing, slowly moving towards the coast and getting longer to the west. This means land is sometimes lost to the sea. The River Glaven can get blocked by the moving shingle, which might cause flooding in Cley village. Because of this, the river's path needs to be changed every few decades.

Contents

What is Blakeney Point?

Blakeney Point is mostly part of the village of Cley next the Sea. The main strip of land runs from west to east. It connects to the mainland at Cley Beach and then continues as a ridge towards Weybourne. This shingle bank is about 6.4 km (4 mi) long. In some places, it's 20 m (65 ft) wide and up to 10 m (33 feet) high. Scientists think there are about 2.3 million m3 (82 million ft3) of shingle here, mostly made of flint.

The Point was created by something called longshore drift. This is when waves move sand and shingle along the coast. The spit is still moving westward; it grew by 132.1 m (433 ft) between 1886 and 1925 alone! At the western end, the shingle curves south towards the mainland. This has happened many times, making it look like a series of hooks from above. Salt marshes have formed in these curved areas and along the sheltered coast. Sand dunes have also built up at the western end of the Point.

The Norfolk Coast Path, a very old walking trail, crosses the southeastern part of the reserve. It follows a sea wall between old farmland and the salt marshes. You can reach the very tip of Blakeney Point by walking along the shingle spit from the car park at Cley Beach. Or, you can take a boat from the quay at Morston. The boat trip offers great views of the seal colonies and saves you a long, tough walk.

The National Trust has an information centre and a tea room at Morston quay. There's also a visitor centre on the Point itself. This centre used to be a lifeboat station and is open during the summer. Halfway House, or the Watch House, is another building about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from Cley Beach car park. It was built in the 1800s for smugglers to watch out for ships. Later, it was used by coast guards and even the Girl Guides.

A Look Back in Time

Norfolk has a very long human history, going back to the Stone Age. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made here. Both modern humans and Neanderthals lived in this area thousands of years ago. The coastline was much further north back then. As the ice melted after the last Ice Age, the sea level rose. This brought the Norfolk coast closer to where it is today. Many ancient sites are now under the sea.

An "eye" is a higher piece of land in the marshes that stays dry enough for buildings. Blakeney's old Carmelite friary, built in 1296, was on such a spot. Pieces of old roof tiles have been found near its ruins. There was also a building called "Blakeney Chapel" that was used from the 1300s to the 1600s. Even though it was called a chapel, it was probably a house. Pottery found there shows that people traded with other countries a lot back then.

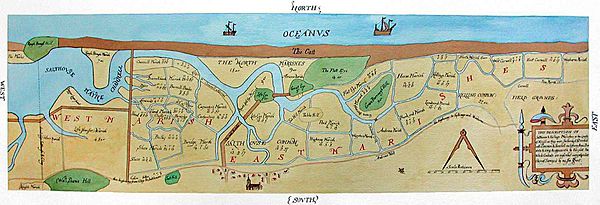

The shingle spit protected the ports along the River Glaven: Blakeney, Cley-next-the-Sea, and Wiveton. These were important harbours in the Middle Ages. Blakeney even sent ships to help King Edward I in 1301. Between the 1300s and 1500s, it was the only Norfolk port with customs officials. Blakeney Church has a second tower at its east end, which is unusual. Some people think it was a beacon to guide ships into the harbour.

Over time, people started reclaiming land, especially in the 1600s. This caused the Glaven shipping channel to fill with mud. Cley's wharf (dock) had to move. More land changes in the 1820s made the problem worse. By 1840, Cley had lost almost all its trade. Blakeney's shipping business did better because its rival was struggling. But eventually, ships became too big for Blakeney's harbour too.

National Trust Takes Over

Before World War I, this coast was famous for hunting wild birds. Locals hunted for food, but some richer visitors hunted to collect rare birds. In 1901, a group called the Blakeney and Cley Wild Bird Protection Society created a bird sanctuary. They hired Bob Pinchen as the first "watcher" to protect the birds.

In 1910, the owner of Blakeney Point, Baron Calthorpe, leased the land to University College London (UCL). When he died, his family put the Point up for sale. People worried it might be developed. So, in 1912, a public appeal helped buy Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe family. The land was then given to the National Trust. UCL set up a research centre at the Old Lifeboat House in 1913. Scientists like Francis Wall Oliver started studying Blakeney Point there. The building is still used by students and as an information centre today.

Blakeney Point became a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1954. Later, it became part of the larger North Norfolk Coast SSSI in 1986. This bigger area is now protected in many ways, including as a Special Protection Area (SPA) for birds and a Ramsar site for wetlands. The Point became a National Nature Reserve (NNR) in 1994. The whole coast, including Blakeney Point, is also a Biosphere Reserve.

Amazing Animals and Plants

Birds of Blakeney Point

Blakeney Point is one of the most important places in Europe for terns to nest. In the early 1900s, people taking eggs and disturbing the birds badly affected the small colonies of common and little terns. But with better protection, the common tern population grew. Today, Blakeney is the most important place in Britain for both Sandwich terns and little terns. About 200 pairs of little terns nest here, which is eight percent of all little terns in Britain!

About 2,000 pairs of black-headed gulls also nest with the terns. They are thought to help protect the whole colony from predators like red foxes. Other birds that nest here include Arctic terns, Mediterranean gulls, ringed plovers, oystercatchers, and common redshanks. Sadly, human disturbance and predators like gulls and stoats have made it harder for some of these birds to have successful nests. Ringed plovers have been especially affected.

Because Blakeney Point sticks out into the sea, it's a great place to see migrant birds in spring and autumn. Sometimes, huge numbers of birds arrive when the weather pushes them towards land. Autumn can bring "falls" of hundreds of European robins or common redstarts. Common birds are often joined by rarer species like greenish warblers. Seabirds can be seen flying past, and migrating waders feed on the marshes. Very rare birds, called vagrants, sometimes show up too.

A scientist named Emma Turner started ringing common terns here in 1909. This technique is still used to study bird migration. One Sandwich tern ringed here was later found in Angola! In winter, the marshes are home to golden plovers and wildfowl like common shelduck, Eurasian wigeon, and brent geese.

Other Wildlife

Blakeney Point has a mixed group of about 500 harbour and grey seals. Harbour seals have their babies between June and August. Their pups can swim almost right away and can be seen on the muddy flats. Grey seals have their young in winter, from November to January. Their pups can't swim until they lose their white fur, so they stay on dry land for their first few weeks. You can see them on the beach during this time. Grey seals started breeding regularly at Blakeney in 2001. Boat trips from Blakeney and Morston harbours are a great way to see the seals without disturbing them.

The rabbit population can grow very large. Their grazing and burrowing can harm the delicate dune plants. When rabbit numbers drop, the plants recover. Carnivores like red foxes, weasels, and stoats hunt the rabbits.

A survey in 2009 found 187 types of beetles here, including some new to Norfolk! There were also 24 kinds of spiders and five ant species. The rare millipede Thalassisobates littoralis, which likes shingle habitats, was found here in 1972. Tens of thousands of turnip sawflies appeared for a few days in 2006.

The tidal flats are full of life, including lugworms, polychaete worms, sand hoppers, and snails. These snails eat the algae on the mud surface. They are an important food source for wading birds. Clams like the edible common cockle also live here, though they are not harvested.

Unique Plants

Grasses like sea couch grass and sea poa grass are very important in the dry parts of the marshes and on the dunes. Here, marram grass, sand couch-grass, and lyme-grass help to hold the sand together. Other special plants that like this dry habitat include sea holly, sand sedge, and pyramidal orchid. Some special mosses and lichens also grow on the dunes, helping to keep the sand in place.

The plants change depending on how old the dunes are and how much moisture they have. Older dunes tend to be more acidic. Mosses and lichens also vary across the dunes. Some moss species are very important for stabilizing the sand. Non-native tree lupins have also started growing wild near the Lifeboat House.

The shingle ridge attracts plants like biting stonecrop, sea campion, yellow horned poppy, and sea thrift. In damper areas where the shingle meets the salt marsh, you can find rock sea lavender and scrubby sea-blite. The saltmarsh itself has plants like European glasswort and common cord grass in the most exposed areas. As the marsh gets older, other plants like sea aster and sea purslane appear.

European glasswort is picked between May and September and sold locally as "samphire." It's a fleshy plant that tastes a bit like asparagus when cooked. It's often eaten with fish. Rabbits also love to eat glasswort.

Visiting Blakeney Point

Millions of visitors come to the Norfolk coast each year, spending lots of money and supporting many jobs. A survey found that 39 percent of visitors to Blakeney and nearby areas came mainly for birdwatching. Besides birdwatching and boat trips to see the seals, sailing and walking are also popular activities.

However, many visitors can sometimes cause problems. Wildlife can be disturbed, especially birds that nest on the ground like ringed plovers and little terns. Plants can also be trampled, which is a big issue in sensitive areas like sand dunes. To help protect the wildlife, the main nesting areas for terns and seals are fenced off during breeding season. A boardwalk made from recycled plastic crosses the large sand dunes. This helps stop erosion and protects the dunes. It was put in place in 2009.

Dogs are not allowed in certain areas from April to mid-August because of the risk to ground-nesting birds. At other times, dogs must be on a lead or kept very close. Conservation groups divide the coast into different zones for tourism. Blakeney Point is in a "red-zone" area. This means it's a sensitive habitat already feeling pressure from visitors. So, no new development or parking improvements are suggested here.

Coastal Changes

The shingle spit at Blakeney Point is quite young in geological terms. Over the last few centuries, it has been moving westward and towards the land. This movement has likely increased because people reclaimed salt marshes along the coast. These marshes used to be a natural barrier to the shingle. A single storm can move a huge amount of shingle. Sometimes, the spit has even been broken through, becoming an island for a while.

Maps from the last two hundred years show how the Blakeney Chapel ruins have gotten closer to the sea. In 1817, they were 400 m (440 yd) from the sea. By the end of the 20th century, they were only 195 m (215 yd) away. The spit is moving towards the mainland by about 1 m (1 yd) each year. Several old "eyes" (raised islands) have already disappeared, first covered by the moving shingle, then lost to the sea. The massive 1953 flood covered the main beach, but the natural parts of the coast, like Blakeney Point, didn't suffer much lasting damage.

Because the shingle was moving inland, the River Glaven channel was getting blocked more and more often by 2004. This caused flooding in Cley village and the important Blakeney freshwater marshes. The Environment Agency decided to create a new path for the river. They moved a 550 m (600 yd) stretch of the river 200 m (220 yd) further south. This work was finished in 2007. The Glaven had been moved before in 1922. Now, the ruins of Blakeney Chapel are north of the new river path. This means they are no longer protected from coastal erosion. The chapel will likely be buried by the moving shingle and then lost to the sea, possibly within 20–30 years.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |