Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gallic Wars | |||||||||

Roman invasion of Britain 54 BC |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Roman Republic | Celtic Britons | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Julius Caesar | Cassivellaunus | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 55 BC 7,000–10,000 legionaries plus cavalry and auxiliaries 100 transport ships 54 BC 17,500–25,000 legionaries 2,000 cavalry 600 transports 28 warships |

Unknown | ||||||||

Julius Caesar, a famous Roman general, invaded Britain twice. These invasions happened in 55 BC and 54 BC, during his larger Gallic Wars in Gaul (modern-day France).

The first time, Caesar brought only two legions (about 7,000-10,000 soldiers). He managed to land on the coast of Kent but didn't achieve much more. The second invasion was much bigger. He had 800 ships, five legions (around 17,500-25,000 soldiers), and 2,000 cavalry. This huge force was so impressive that the Britons didn't try to stop his landing.

Caesar's army moved inland, reaching Middlesex and crossing the Thames River. He forced a powerful British leader named Cassivellaunus to surrender. Cassivellaunus agreed to pay tribute to Rome. Caesar also set up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes tribe as a friendly king, loyal to Rome.

Caesar wrote about both invasions in his book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico. These writings are important because they are the first detailed eyewitness accounts of Britain. They describe the people, their culture, and the island's geography. This marks the beginning of Britain's written history.

Contents

Britain Before Caesar's Arrival

For a long time, people in the ancient world knew Britain as a place that supplied tin. The Greek explorer Pytheas had sailed around its coast in the 4th century BC. Some Romans, however, thought Britain was a mysterious land beyond the known world. Some even doubted it existed!

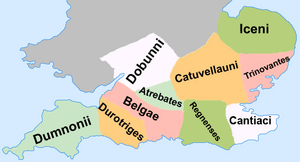

During Caesar's time, Britain had an Iron Age culture. Experts believe between one and four million people lived there. The economy was different in the lowlands (southeast) and highlands (north). In the lowland southeast, fertile soil allowed for lots of farming. People used ancient paths and rivers like the Thames for travel and trade.

In the highlands, farming was harder. People mostly raised animals and grew small gardens. Settlements were often built on high, fortified ground. But in the southeast, larger towns called oppida started appearing near rivers. This showed that trade was becoming more important.

Trade between Britain and Europe grew after Rome conquered Gaul in 124 BC. Italian wine, for example, was imported into Britain. Caesar wrote that the Belgae people from northeastern Gaul had raided Britain before. They even set up settlements along the coast.

Why Caesar Invaded Britain

Caesar had been conquering Gaul since 58 BC. By 56 BC, he controlled most of northwest Gaul. He said he invaded Britain because the Britons had helped his enemies, the Gauls, in their wars against Rome. Some Gallic people had fled to Britain, and the Veneti tribe, who controlled sea trade, had asked their British allies for help against Caesar.

Another reason for the invasion might have been to explore Britain's resources. Caesar wanted to see if there was gold or silver on the island. Later, people said he was looking for pearls.

However, a big reason was probably for Caesar to gain more fame and power in Rome. His rivals, Pompey and Crassus, were very powerful. Caesar needed to impress the Roman people. By crossing the Rhine River and the English Channel—something no Roman army had done before—he would become a huge hero.

First Invasion (55 BC)

Planning the Expedition

Caesar tried to get information from merchants who traded with Britain. But they didn't want to share their secrets about the island or its harbors. So, Caesar sent a military officer, Gaius Volusenus, to scout the coast. Volusenus probably checked the Kent coast but couldn't land. He returned after five days with what little information he had.

Meanwhile, some British leaders, warned by merchants, sent ambassadors to Caesar. They promised to surrender. Caesar sent them back with his ally, Commius, a king from Gaul. Commius was to convince more British tribes to join Rome.

Caesar gathered a fleet of 80 transport ships. These ships could carry two legions (Legio VII and Legio X). He also had some warships. Another 18 ships were for cavalry. Caesar decided to sail for Britain in late summer 55 BC, even though it was late in the fighting season.

Landing in Britain

Caesar set out before dawn on August 23. He left without his cavalry, which was a risky move. He wanted to arrive at dawn.

When he reached the coast, he saw many Britons gathered on the hills. They were ready to fight. Caesar waited until about 3 PM, then ordered his fleet to sail northeast. He found an open beach, probably at Ebbsfleet.

The Britons followed along the coast. They had a strong force, including cavalry and chariots. The Roman soldiers were hesitant to land. Their ships were too low in the water to get close to shore. The troops had to jump into deep water while the enemy attacked them from the shallows.

Finally, a brave standard bearer from the legion jumped into the sea. He waded ashore. To lose the legion's standard in battle was a great shame. So, the other soldiers followed him to protect it. After some fighting, the Romans formed a battle line, and the Britons retreated. Caesar's cavalry couldn't make the crossing, so he couldn't chase them.

Building a Beach-head

Recent discoveries by the University of Leicester suggest the landing beach was at Ebbsfleet in Pegwell Bay. They found ancient artifacts and large earthworks there. If Caesar had a huge fleet, his ships might have landed along several miles of coastline.

The Ebbsfleet site was a defensive area. It was on a peninsula that jutted into a channel. This area was perfect for setting up a camp.

Small Fights and Challenges

The Romans set up their camp. They received ambassadors, and Commius, who had been arrested by the Britons, was returned to them. Caesar said the British leaders blamed their attacks on common people. He claimed they were so impressed that they agreed to give hostages and disband their army within four days.

However, things quickly went wrong for Caesar. His cavalry ships were scattered by storms and forced back to Gaul. Food supplies started running low. Then, high British tides and a storm surprised Caesar. His ships on the beach filled with water. His transport ships, anchored offshore, crashed into each other. Many ships were wrecked or badly damaged. This threatened his return journey.

The Britons saw this and hoped to trap Caesar in Britain for the winter. They attacked again, ambushing a Roman legion that was looking for food. The rest of the Roman army came to help, and the Britons were driven off. After more storms, the Britons attacked the Roman camp with a larger force. But the Romans, with some help from friendly Britons and a "scorched earth" tactic (destroying everything so the enemy couldn't use it), drove them off again.

The fighting season was ending. Caesar's legions couldn't stay in Kent for the winter. He quickly repaired as many ships as possible using wood from the wrecked ones. Then, he sailed back across the Channel.

What Was Achieved?

Caesar barely escaped disaster. Taking a small army with few supplies to a distant land was a bad plan. But he survived. He didn't gain much land in Britain. Yet, just landing there was a huge achievement.

It was a great propaganda victory for him. His book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, kept Rome updated on his adventures. This helped him gain enormous fame and public support. When he returned to Rome, he was celebrated as a hero. He received an amazing 20-day thanksgiving celebration.

Second Invasion (54 BC)

Getting Ready for the Next Invasion

Caesar learned from his first trip. Over the winter of 55–54 BC, he prepared much better. New ships were built. They were wider and lower, making them easier to land on beaches. This time, Caesar brought 800 ships, five legions, and 2,000 cavalry. He left the rest of his army in Gaul to keep order. He also brought many Gallic chiefs with him. He didn't trust them and wanted to keep an eye on them.

He chose Portus Itius as the starting point for this invasion.

Crossing the Channel and Landing

Titus Labienus stayed at Portus Itius. His job was to send regular food supplies to the British beachhead. Many trading ships joined the military fleet. Roman and Gallic traders hoped to make money from new trading chances. Caesar's number of 800 ships probably included these trading vessels.

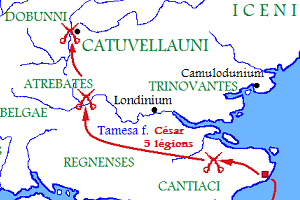

The Roman fleet sailed from France in the evening. They wanted to land in Britain during daylight. The wind helped them cross the Channel. But at midnight, the wind died down. The tide carried them too far northeast. At sunrise, they saw Britain on their left. They had to row and use the tide to get back to the best landing spot from the year before.

The Britons had gathered to stop them. But when they saw the huge Roman fleet, they were scared. Caesar said they "withdrew and concealed themselves on the high ground." This gave them time to gather their forces. Caesar landed and immediately went to find the British army.

Campaign in Kent

After landing, Caesar left Quintus Atrius in charge of the beach-head. Atrius had about a legion of soldiers to build and defend the base. Caesar then marched about 12 miles (19 km) inland that same night. He met the British forces at a river crossing, probably on the River Stour.

The Britons attacked but were pushed back. They tried to regroup in a fortified forest area, possibly Bigbury Wood. But they were defeated again and scattered. It was late, and Caesar didn't know the area well, so he stopped the chase and made camp.

The next morning, Caesar was ready to move forward. But he got bad news from Atrius. Another storm had hit his ships at anchor. About 40 ships were lost. The Romans weren't used to the strong tides and storms of the Atlantic and English Channel. This was poor planning by Caesar, especially after the damage from the previous year. However, Caesar might have exaggerated the number of lost ships to make his rescue efforts seem even greater.

He returned to the coast and called back the legions that had gone ahead. His men worked day and night for about ten days. They pulled the ships onto the beach, repaired them, and built a strong camp around them. He also sent a message to Labienus to send more ships.

Marching Inland

Caesar then went back to the Stour crossing. He found the Britons had gathered their forces there again. Cassivellaunus, a warlord from north of the Thames, was chosen to lead the combined British forces. He had previously fought with other British tribes. He had even overthrown the king of the powerful Trinovantes tribe, forcing the king's son, Mandubracius, into exile.

After some small fights, the Britons attacked a group of Roman soldiers who were looking for food. But the Romans fought them off. Cassivellaunus realized he couldn't beat Caesar in a big battle. So, he sent most of his army away. He relied on his 4,000 chariots and his knowledge of the land. He used guerrilla tactics, making quick attacks and then disappearing, to slow down the Roman advance.

When Caesar reached the Thames, the only place he could cross was fortified. There were sharpened stakes on the shore and under the water. The other side of the river was defended. Some old stories say Caesar used a war elephant to scare the defenders away. When this strange animal entered the river, the Britons and their horses fled. The Roman army then crossed into Cassivellaunus's territory. (But this story might be a mix-up with Claudius's invasion in AD 43, when elephants were definitely used.)

The Trinovantes tribe, who had suffered under Cassivellaunus, sent messengers to Caesar. They promised to help him with food and supplies. Mandubracius, the exiled son, was made their king again. The Trinovantes gave Caesar grain and hostages. Five other tribes also surrendered to Caesar. They told him where Cassivellaunus's stronghold was, possibly a hill fort at Wheathampstead. Caesar then began to besiege it.

Cassivellaunus sent word to his allies in Kent to attack the Roman beach-head. They hoped to draw Caesar away. But this attack failed. So, Cassivellaunus sent messengers to negotiate a surrender. Caesar wanted to return to Gaul for the winter because there was growing unrest there. An agreement was made with the help of Commius. Cassivellaunus gave hostages, agreed to pay a yearly tribute, and promised not to fight Mandubracius or the Trinovantes.

Caesar wrote to Cicero on September 26, confirming the results. He said he got hostages but no valuable loot. His army was about to return to Gaul. He left Britain without a single Roman soldier to enforce the agreement. We don't know if the tribute was ever truly paid.

Caesar demanded grain, slaves, and a yearly payment to Rome. However, Britain wasn't very rich at the time. Cicero joked that there was "not a scrap of silver in the island and no hope of booty except for slaves." Still, this second trip was a true invasion. Caesar achieved his goals. He had defeated the Britons and made them pay tribute. They were now, in a way, under Roman influence. Caesar was lenient because he needed to leave before stormy weather made crossing the Channel impossible.

After Caesar's Invasions

Commius, Caesar's ally, later switched sides and fought against Caesar in Gaul. After some defeats, he fled to Britain. One story says that Commius and his followers boarded their ships while the tide was out. He ordered the sails raised. Caesar, still far away, thought the ships were floating and stopped chasing them. Some historians believe this story is a legend. Commius may have been sent to Britain as a friendly king as part of a truce.

Commius started a ruling family in the Hampshire area of Britain. We know this from coins found there. Verica, a king whose exile later led to Claudius's conquest in AD 43, claimed to be a son of Commius.

What Caesar Learned About Britain

Caesar wrote about British warfare, especially their use of chariots. This was new to the Romans, who used chariots for transport and racing. He also tried to learn about Britain's geography, weather, and people. He probably got this information from asking questions and hearing stories, not from exploring much himself. Most historians agree his findings apply mainly to the tribes he met.

Geography and Weather

Caesar's direct discoveries were limited to east Kent and the Thames Valley. But he gave a description of the island's geography and weather. His measurements weren't perfect, but his general ideas are still considered true:

- The climate is milder than in Gaul, with less severe cold.

- The island is shaped like a triangle. One side faces Gaul. One corner of this side, in Kent, faces east. The lower corner faces south. This side is about 500 miles long.

- Another side faces Spain and the west. Ireland is on this side, about half the size of Britain. The journey from Ireland to Britain is the same distance as from Gaul to Britain. In the middle of this journey is an island called Mona. Many smaller islands are also there. Some say that during winter, it's night for 30 days straight on some of these islands. Caesar said he found the nights were shorter there than on the continent. This side is about 700 miles long.

- The third side faces north. No land is opposite this part. One corner of this side faces Germany. This side is about 800 miles long. So, the whole island is about 2,000 miles around.

Before Caesar's trips, Romans knew nothing about Britain's harbors. Caesar's discoveries helped Roman military and trade interests. His scout, Volusenus, probably found the natural harbor at Dubris (Dover). But Caesar couldn't land there. He had to land on open beaches, perhaps because Dover was too small for his large forces. The great natural harbors further up the coast at Rutupiae (Richborough), used by Claudius 100 years later, were not used by Caesar. He might not have known about them, or they might not have been suitable then.

By Claudius's time, Roman knowledge of Britain had grown a lot from a century of trade and diplomacy. It's likely that the information Caesar gathered in 55 and 54 BC was kept in Roman records and used by Claudius for his invasion plans.

People and Culture

Caesar described the Britons as typical "barbarians." He noted their polygamy (having multiple wives) and other unusual social habits. He said they were similar to the Gauls but also brave enemies.

- The people living inland were said to be the original inhabitants. Those on the coast had come from Gaul to raid and settle.

- The population was huge, and they had many buildings, similar to those in Gaul.

- They didn't eat hare, cock (rooster), or goose. But they raised them for fun.

- The people in Kent were the most civilized. They were very similar to the Gauls.

- Most inland people didn't grow grain. They lived on milk and meat and wore animal skins.

- All Britons dyed themselves with woad, which made them look bluish. This made them look more terrifying in battle.

- They wore their hair long and shaved all their bodies except their heads and upper lips.

- Ten or even twelve men shared wives, especially brothers among brothers, and parents among their children. If children were born, they were considered the children of the man who first married the mother.

Military Tactics

Besides foot soldiers and cavalry, the Britons used chariots in battle. This was new to the Romans. Caesar described how they used them:

- They drove chariots in all directions, throwing weapons. The fear of the horses and the noise of the wheels broke enemy lines.

- When they were among the enemy's horse troops, they would jump from their chariots and fight on foot.

- The charioteers would move a short distance away. They would wait with the chariots so their masters could quickly retreat if they were overwhelmed.

- This way, they combined the speed of horses with the strength of infantry. They practiced daily and became very skilled. They could stop their horses at full speed on a steep slope. They could turn them instantly, run along the pole, stand on the yoke, and quickly get back into their chariots.

Technology

During his later civil war, Caesar used a type of boat he had seen in Britain. These boats were like the Irish currach or Welsh coracle. He described them:

- The bottom (keels) and sides (ribs) were made of light wood.

- The rest of the boat was made of wickerwork (woven branches) and covered with animal hides.

Religion

Caesar noted that the religion of Druidism was thought to have started in Britain. He said that people who wanted to learn more about it often went to Britain to study.

Economic Resources

Caesar also investigated Britain's economic resources. He wanted to show that Britain could be a rich source of tribute and trade for Rome:

- There were many cattle.

- They used brass or iron rings, weighed to a certain amount, as money.

- Tin was found in the middle of the island. Iron was found near the coast, but not much. They used brass that was imported.

- There was every kind of timber, except beech and fir.

Caesar's idea that tin came from the "midland" was wrong. Tin production and trade were actually in the southwest of England, in Cornwall and Devon. But since Caesar only went as far as Essex, he might have heard reports of trade coming from inland areas.

What Happened Next?

Caesar didn't conquer Britain permanently. But by putting Mandubracius on the throne, he started a system of client kingdoms there. This brought Britain into Rome's political influence. Trade and diplomatic ties grew over the next century. This eventually led to the full Roman conquest, which began under Claudius in AD 43.

As the Roman historian Tacitus wrote: "It was, in fact, the deified Julius who first of all Romans entered Britain with an army: he overawed the natives by a successful battle and made himself master of the coast; but it may be said that he revealed, rather than bequeathed, Britain to Rome."

Some Roman writers, like Lucan, even joked that Caesar had "run away in terror from the Britons whom he had come to attack!"

Caesar's Invasions in Later Stories

Ancient and Medieval Stories

- Valerius Maximus (1st century AD) wrote about the bravery of Marcus Caesius Scaeva, a Roman officer. He held his ground alone against many Britons on a small island before swimming to safety.

- Polyaenus (2nd century AD) told the story of Caesar using an armored elephant to cross a river. This terrified the Britons into fleeing.

- Bede's History of the English Church and People (8th century) includes an account of Caesar's invasions, mostly taken from an earlier writer named Orosius.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (12th century) tells a very different story. Caesar invades three times, not twice. He fights Cassibelanus (Cassivellaunus). In this story, Cassibelanus's brother, Nennius, fights Caesar hand-to-hand and steals his sword, Crocea Mors.

Modern Popular Culture

- In Robert Graves's novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God, Caesar's invasions are mentioned. In the TV show based on the books, young Roman royals play a board game about conquering the empire and argue about how many legions are needed for Britain.

- The 1965 comic Asterix in Britain by Goscinny and Uderzo humorously shows Caesar conquering Britain. In the comic, the Britons stop fighting every afternoon for tea and on weekends, which the Romans use to their advantage.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |