Camille Saint-Saëns facts for kids

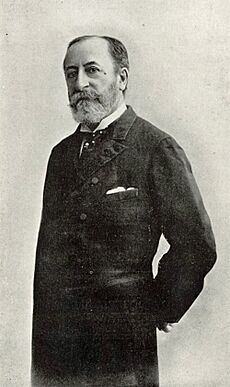

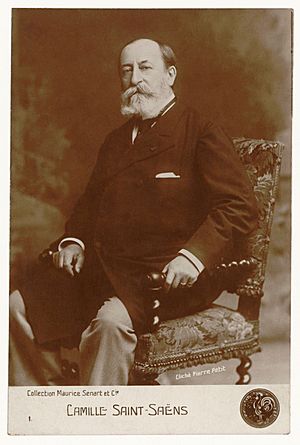

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (born October 9, 1835 – died December 16, 1921) was a famous French composer, organist, conductor, and pianist. He lived during the Romantic era of music. Some of his most well-known pieces include The Carnival of the Animals, the Third ("Organ") Symphony, and the opera Samson and Delilah.

Saint-Saëns was a child prodigy, meaning he was incredibly talented from a very young age. He performed his first concert when he was just ten years old. After studying at the Paris Conservatoire, he became a church organist. He worked at Saint-Merri and then at La Madeleine, which was a very important church in Paris. After twenty years, he became a freelance musician, performing and composing across Europe and the Americas.

When he was young, Saint-Saëns loved the newest music by composers like Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner. However, his own music usually followed more traditional classical styles. He knew a lot about music history and liked the structures used by earlier French composers. Later in his life, this sometimes caused disagreements with composers who wrote in newer styles like Impressionism. Even though his music sometimes had elements that were ahead of his time, he was often seen as old-fashioned by the time he died.

Saint-Saëns only taught music for a short time, less than five years, at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse in Paris. But this was very important for French music because his students included Gabriel Fauré. Fauré later taught Maurice Ravel, and both of them were greatly influenced by Saint-Saëns, whom they admired as a genius.

Life of Saint-Saëns

Early Years

Camille Saint-Saëns was born in Paris. He was the only child of Jacques-Joseph-Victor Saint-Saëns and Françoise-Clémence. His father worked for the French government but sadly died when Camille was less than two months old. Young Camille was taken to the countryside for his health and lived with a nurse for two years.

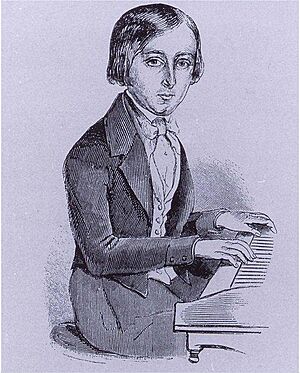

When he returned to Paris, Camille lived with his mother and her aunt, Charlotte Masson. Before he was three years old, he showed amazing musical talent. He had perfect pitch (meaning he could identify any musical note he heard) and loved playing tunes on the piano. His great-aunt taught him the basics of piano. When he was seven, he started lessons with Camille-Marie Stamaty, a famous piano teacher.

His mother didn't want him to become famous too young, even though he was incredibly gifted. A music critic once said that Saint-Saëns was "the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart." He gave small performances from age five. His official public debut was at age ten at the Salle Pleyel. He played a piano concerto by Mozart and another by Beethoven. Through his teacher, Saint-Saëns also met Pierre Maleden, a composition professor, and Alexandre Pierre François Boëly, an organ teacher. From Boëly, he learned to love the music of Bach, which was not very well known in France at that time.

Saint-Saëns was also an excellent student in many other subjects. Besides music, he was good at French literature, Latin, Greek, religion, and mathematics. He was also interested in philosophy, archaeology, and astronomy. He remained a talented amateur astronomer throughout his life.

In 1848, at age thirteen, Saint-Saëns was accepted into the Paris Conservatoire, France's top music school. Students were encouraged to study the organ because being a church organist offered more job opportunities than being a solo pianist. His organ teacher was François Benoist. In 1849, Saint-Saëns won second prize for organists, and in 1851, he won the top prize. That same year, he began formal composition studies with Fromental Halévy.

As a student, Saint-Saëns wrote a symphony and a choral piece. In 1852, he tried to win France's top music award, the Prix de Rome, but he didn't succeed. However, he won first prize in another competition with his piece Ode à Sainte-Cécile. His first mature work that he officially recognized was Trois Morceaux for harmonium in 1852.

Becoming a Musician

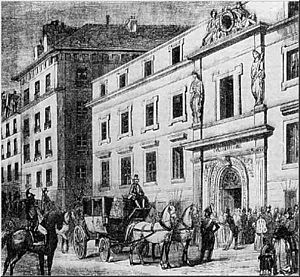

After leaving the Conservatoire in 1853, Saint-Saëns became the organist at the old Parisian church of Saint-Merri. This job gave him a good income and plenty of time to work on his piano playing and composing. He wrote his Symphony in E-flat (1853), which won him another first prize from the Société Sainte-Cécile.

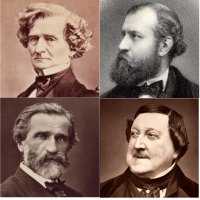

Many famous musicians quickly recognized Saint-Saëns's talent, including the composers Gioachino Rossini, Hector Berlioz, and Franz Liszt. They all encouraged his career. In 1858, Saint-Saëns moved to a more important job as organist at La Madeleine, the official church of the French Empire. Liszt heard him play there and called him the greatest organist in the world.

Even though he later became known for being musically traditional, in the 1850s Saint-Saëns supported new music by Liszt, Robert Schumann, and Richard Wagner. He admired Wagner's operas but was not influenced by them in his own compositions. He once said, "I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion."

Teacher and Growing Fame

In 1861, Saint-Saëns took his only teaching job at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse in Paris. He surprised some of his colleagues by teaching his students modern music, including works by Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner. He also wrote a funny play with music for his students to perform. He first thought of his most famous piece, The Carnival of the Animals, with his students in mind, but he didn't finish it until 1886.

In 1864, Saint-Saëns tried for the Prix de Rome again, but he didn't win. Many people were surprised he entered the competition again since he was already becoming famous. The composer Berlioz famously joked about Saint-Saëns, "He knows everything, but lacks inexperience." This meant Saint-Saëns was very skilled but perhaps didn't show enough raw, untamed genius. Some critics felt he was more technically perfect than deeply emotional. Saint-Saëns himself wrote, "Art is intended to create beauty and character. Feeling only comes afterwards and art can very well do without it."

After leaving the teaching school in 1865, Saint-Saëns focused strongly on composing and performing. In 1867, his cantata Les noces de Prométhée won a major prize in Paris. The judges included famous composers like Auber, Berlioz, Gounod, Rossini, and Giuseppe Verdi. In 1868, he premiered his Second Piano Concerto, which became one of his most popular orchestral works. He became a well-known musician in Paris and other cities during the 1860s.

War, Marriage, and Opera Success

In 1870, Saint-Saëns and Romain Bussine decided to create a society to promote new French music. This was because German music was very popular, and young French composers didn't have many chances to have their works performed. Before they could do much, the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Saint-Saëns served in the National Guard. During the Paris Commune in 1871, he escaped to England for a short time. When he returned to Paris, people were more eager to support French music. The Société Nationale de Musique was formed in February 1871, with Saint-Saëns as vice-president.

Saint-Saëns admired Liszt's symphonic poems (orchestral pieces that tell a story or describe something), and he wrote his first one, Le Rouet d'Omphale (1871). In the same year, one of his operas was finally performed. La princesse jaune ("The Yellow Princess"), a short, light opera, was shown in Paris in June.

For many years, Saint-Saëns lived with his mother. In 1875, he surprised many people by getting married. He was almost forty, and his bride, Marie-Laure Truffot, was nineteen. The marriage was not happy. Saint-Saëns's mother didn't approve, and he was a difficult person to live with. Sadly, their two young sons passed away, which deeply affected their marriage.

For a French composer in the 19th century, writing operas was very important. In February 1877, Saint-Saëns finally had a full-length opera performed. His four-act opera, Le timbre d'argent ("The Silver Bell"), had been planned earlier but was stopped by the war. It was performed eighteen times.

After this, a friend named Albert Libon died and left Saint-Saëns a large amount of money. This allowed Saint-Saëns to quit his job as an organist at the Madeleine and focus entirely on composing. He was tired of the church authorities and wanted to be free to perform as a piano soloist in other cities. He never played the organ professionally in a church again. He wrote a Messe de Requiem (a mass for the dead) in memory of his friend.

In December 1877, Saint-Saëns had a much bigger opera success with Samson et Dalila. This is his only opera that is still regularly performed around the world. Because it was based on a biblical story, it was difficult to get it performed in France. So, with Liszt's help, it premiered in Germany. It didn't play at the Paris Opéra until 1892.

Saint-Saëns loved to travel. From the 1870s until he died, he made 179 trips to 27 countries. He often went to Germany and England for work. For holidays, and to avoid the cold Parisian winters that affected his health, he often went to Algiers and different places in Egypt.

An International Star

Saint-Saëns was elected to the Institut de France in 1881. In July of that year, he and his wife went on holiday. On July 28, he left their hotel and sent his wife a letter saying he would not return. They never saw each other again. Marie Saint-Saëns returned to her family. Saint-Saëns did not divorce or remarry. After the loss of his children and the end of his marriage, Saint-Saëns found a new family in his student Gabriel Fauré, Fauré's wife Marie, and their two sons. He was like a beloved uncle to them.

In the 1880s, Saint-Saëns continued to try for success in opera. Many important musicians believed that a pianist, organist, and symphonist couldn't write a good opera. He had two operas performed during this time. The first was Henry VIII (1883), which was commissioned by the Paris Opéra. Even though he didn't choose the story, Saint-Saëns worked very hard to make the music sound like 16th-century England. The opera was a success and was performed many times during his life.

By the mid-1880s, the Société Nationale, which Saint-Saëns helped create, was becoming too focused on Wagner's style of music. Saint-Saëns and Bussine disagreed with this and resigned in 1886. Saint-Saëns had always promoted Wagner's music in France, but now he worried that it was having too much influence on young French composers. His caution towards Wagner grew into stronger dislike later, partly because of Wagner's political nationalism.

By the 1880s, Saint-Saëns was very popular with audiences in England, where he was seen as the greatest living French composer. In 1886, the Philharmonic Society of London asked him to write a piece. This became one of his most popular works, the Third ("Organ") Symphony. It premiered in London, with Saint-Saëns conducting and also playing the piano in a Beethoven concerto. The symphony was a huge success in London and even more so in Paris the next year. Later in 1887, his opera Proserpine opened, but the theater burned down soon after, and the production was lost.

In December 1888, Saint-Saëns's mother died. He was very sad and suffered from depression and trouble sleeping. He left Paris and stayed in Algiers, where he recovered until May 1889. He walked and read but couldn't compose during this time.

Later Years and Legacy

In the 1890s, Saint-Saëns spent a lot of time on holiday, traveling overseas. He composed less and performed less often. He wrote one opera, the comedy Phryné (1893). His major concert pieces from this decade were the Africa fantasia (1891) and his Fifth ("Egyptian") Piano Concerto. He premiered the concerto in 1896 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of his first public performance.

He performed at Cambridge University in June 1893, where he, Bruch, and Tchaikovsky received honorary degrees. Saint-Saëns enjoyed the visit and even liked the college chapel services, saying, "The demands of English religion are not excessive. The services are very short, and consist chiefly of listening to good music extremely well sung, for the English are excellent choristers." His respect for British choirs continued, and one of his last large works, the oratorio The Promised Land, was written for the Three Choirs Festival in 1913.

In 1900, Saint-Saëns moved into a new flat in Paris, which remained his home for the rest of his life. He continued to travel often, giving concerts in London, Berlin, Italy, Spain, and the United States. In 1906 and 1909, he had very successful tours in the US as a pianist and conductor.

Even though he was seen as old-fashioned in music, Saint-Saëns was probably the only French musician to travel to Munich to hear the premiere of Mahler's Eighth Symphony in 1910. However, by the 20th century, he had lost much of his interest in modern music. He didn't understand or like his student Fauré's opera Pénélope (1913), even though it was dedicated to him. He also strongly disliked the new styles of composers like Debussy and Stravinsky. He famously said that Stravinsky was insane after hearing his ballet The Rite of Spring.

During the First World War, Saint-Saëns tried to organize a boycott of German music. Fauré and Messager disagreed with this, but it didn't affect their friendship. They worried that Saint-Saëns was becoming too patriotic and publicly criticizing young composers. He successfully blocked Debussy from being elected to the Institut, which caused anger among Debussy's supporters. He also criticized the music of Les Six, a group of young French composers, saying that for Darius Milhaud's polytonal suite, "fortunately, there are still lunatic asylums in France."

Saint-Saëns gave what he planned to be his farewell concert as a pianist in Paris in 1913. But his retirement was put on hold because of the war. He gave many performances to raise money for war charities, even traveling across the Atlantic despite the danger from German submarines.

In November 1921, Saint-Saëns gave a recital in Paris. People noted that his playing was still lively and precise, and he looked amazing for an eighty-six-year-old. He left Paris a month later for Algiers, planning to spend the winter there as he often did. He died suddenly of a heart attack on December 16, 1921. His body was brought back to Paris for a state funeral at the Madeleine church, and he was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery. His widow, Marie-Laure, whom he hadn't seen since 1881, was among the mourners.

His Music

Even though Saint-Saëns was a modernist in his youth, he always respected the great composers of the past. He loved classical masters like Rameau, Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Mozart. This deep knowledge formed the basis of his art.

Unlike some of his French contemporaries who were drawn to Wagner's continuous music style, Saint-Saëns often preferred clear, self-contained melodies. His melodies are often flexible and graceful, usually built in three or four-bar sections. He sometimes used a neoclassical style, influenced by his study of French baroque music. He created his orchestral effects more through interesting harmonies and rhythms than by using unusual instruments. He was a master of counterpoint (combining different melodies), and these passages appear naturally in many of his works.

Orchestral Works

Saint-Saëns's brilliant musical skills helped French musicians realize that there were other types of music besides opera. His First Symphony (1853) is a serious and grand work, showing the influence of Schumann. The Second Symphony (1859) is praised for its efficient use of the orchestra and strong structure, with parts that show his mastery of fugal writing.

The most famous of his symphonies is the Third (1886), often called the "Organ" Symphony because it has important parts for piano and organ. It starts in a serious C minor and ends in a grand C major with a majestic tune. The work is dedicated to the memory of Liszt and uses a repeating musical idea that changes throughout the piece, like Liszt's style.

Saint-Saëns's four symphonic poems are like those by Liszt. The most popular is Danse macabre (1874), which describes skeletons dancing at midnight. In this piece, he famously used the xylophone to represent the rattling bones of the dancers. Le Rouet d'Omphale (1871) is light and delicately orchestrated. Phaëton (1873) is considered by some to be the best of his symphonic poems, beautifully showing the mythical hero and his fate. The last symphonic poem, La jeunesse d'Hercule ("Hercules's Youth", 1877), was the most ambitious. These orchestral works, with their striking melodies, strong structure, and memorable orchestration, set new standards for French music and inspired younger composers like Ravel.

Saint-Saëns also wrote a one-act ballet, Javot (1896), the music for the film L'assassinat du duc de Guise (1908), and music for many plays. For revivals of classic plays, he used his deep knowledge of French baroque music, including music by Lully and Charpentier.

Concertos

Saint-Saëns was the first major French composer to write piano concertos. His First, in D (1858), is not well known, but the Second, in G minor (1868), is one of his most popular works. In this piece, he experimented with the form, starting with a serious solo section. The fast second movement and very fast finale are so different from the opening that one pianist joked it "begins like Bach and ends like Offenbach." The Third Piano Concerto, in E-flat (1869), also has a lively finale, but the earlier movements are more classical and clear.

The Fourth, in C minor (1875), is probably his best-known piano concerto after the Second. It has two movements, each with two clear parts, and a strong musical theme that connects the whole piece. Some say this piece impressed Gounod so much that he called Saint-Saëns "the Beethoven of France." The Fifth and last piano concerto, in F major, was written in 1896. It's known as the "Egyptian" concerto because he wrote it while in Luxor, Egypt, and it includes a tune he heard Nile boatmen singing.

The First Cello Concerto, in A minor (1872), is a serious but lively work in one continuous movement. It's very popular among cellists. The Second, in D minor (1902), is more focused on showing off the soloist's skill. Saint-Saëns told Fauré it would never be as popular as the First because it was too difficult.

He wrote three violin concertos. The Third, in B minor, was written for the famous violinist Pablo de Sarasate. It is technically challenging for the soloist, but it also has calm and peaceful parts. It is by far the most popular of his violin concertos. However, Saint-Saëns's most famous work for violin and orchestra is probably the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), also written for Sarasate. This single-movement piece changes from a thoughtful and tense opening to a lively main theme.

Operas

Saint-Saëns wrote twelve operas. During his lifetime, his opera Henry VIII was often performed. Since his death, only Samson et Dalila has been regularly staged. Some experts believe Ascanio (1890) is a much finer work. Critics say that Saint-Saëns, despite his experience and skill, didn't have the natural "feel" for theater that composers like Massenet had.

Even though most of Saint-Saëns's operas are not well known today, they are important in the history of French opera. They act as a bridge between earlier composers like Meyerbeer and the serious French operas of the 1890s. His operas generally have the same strengths and weaknesses as the rest of his music: clear, Mozart-like transparency, more care for form than for deep emotion. There can be a certain emotional dryness, and sometimes the ideas are thin, but the craftsmanship is perfect.

Saint-Saëns used different styles in his operas. From Meyerbeer, he learned how to use the chorus effectively. For Henry VIII, he included music from the Tudor era that he had researched in London. In La princesse jaune, he used an oriental pentatonic scale. From Wagner, he used leitmotifs (short musical ideas linked to characters or themes), but he used them sparingly.

Other Vocal Music

From age six until he died, Saint-Saëns composed over 140 mélodies (French art songs). He believed his songs were truly French and not influenced by German composers like Schubert. Unlike his student Fauré, he didn't write many song cycles (groups of songs meant to be performed together). He often set poems by Victor Hugo, but also by Alphonse de Lamartine, Pierre Corneille, and others. He even wrote the words for eight of his own songs. He was very careful about how the words fit the music. Most of his songs are for voice and piano, but a few are for voice and orchestra.

Saint-Saëns composed more than sixty sacred vocal works, including motets, masses, and oratorios. Larger works include the Requiem (1878) and the oratorios Le déluge (1875) and The Promised Land (1913). He was proud of his connection with British choirs, saying, "One likes to be appreciated in the home, par excellence, of oratorio." He wrote fewer secular choral works. In his choral music, Saint-Saëns followed the tradition of earlier masters like Handel and Mendelssohn.

Piano and Organ Music

Even though Saint-Saëns was a famous pianist and wrote piano music throughout his life, this part of his work is not as well known. One exception is the Étude en forme de valse (1912), which pianists still enjoy playing to show off their left-hand technique. Although he was called "the French Beethoven," Saint-Saëns did not write piano sonatas. He wrote sets of bagatelles (1855), études (1899 and 1912), and fugues (1920). Most of his piano works are short, individual pieces, often descriptive, like "Souvenir d'Italie" (1887) or "Les cloches du soir" ("Evening bells", 1889).

Unlike his student Fauré, who was an organist but didn't write much for the instrument, Saint-Saëns published a modest number of pieces for solo organ. Some were for church services, like "Offertoire" (1853) and "Bénédiction nuptiale" (1859). After he left the Madeleine church in 1877, he wrote ten more organ pieces, mostly for concerts.

Chamber Music

Saint-Saëns wrote over forty chamber works (music for a small group of instruments) throughout his life. One of his first major chamber works was the Piano Quintet (1855), a confident piece with a traditional structure. The Septet (1880) is for an unusual combination of trumpet, two violins, viola, cello, double bass, and piano. It's a neoclassical work that uses 17th-century French dance forms. Other examples of his sometimes unusual instrument combinations include the Caprice sur des airs danois et russes (1887) for flute, oboe, clarinet, and piano, and the Barcarolle in F major (1898) for violin, cello, harmonium, and piano.

Some of his most important chamber works are his sonatas: two for violin, two for cello, and one each for oboe, clarinet, and bassoon, all with piano accompaniment. The First Violin Sonata (1885) is considered one of his best and most typical compositions. The Second (1896) shows a change in his style, with a lighter, clearer sound for the piano. The First Cello Sonata (1872) is a serious work where the cello carries the main melody over a brilliant piano part.

His woodwind sonatas (oboe, clarinet, bassoon) are among his last works. He wrote them to expand the music available for these instruments, which didn't have many solo pieces. These sonatas have clear, classical lines, beautiful melodies, and excellent structures. The Oboe Sonata starts like a traditional classical sonata, with a graceful theme. The Clarinet Sonata is considered a masterpiece, full of playfulness, elegance, and quiet beauty. The Bassoon Sonata is a model of clarity, energy, and lightness, with humorous touches and peaceful moments.

His most famous work, The Carnival of the Animals (1887), is written for eleven players and is considered part of his chamber music. It's a brilliant and funny piece that makes fun of other composers and popular tunes. He didn't allow it to be performed during his lifetime because he worried its lightheartedness would harm his reputation as a serious composer.

Recordings

Saint-Saëns was one of the first composers to have his music recorded. In 1904, The Gramophone Company recorded him playing his own piano music and accompanying a singer. He made more recordings in 1919.

In the early days of LP records, not many of Saint-Saëns's works were available. But later, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many more of his compositions were released on CDs and DVDs. Today, you can find recordings of almost all his concertos, symphonies, symphonic poems, and sonatas.

Most of his operas, except for Samson et Dalila, have not been recorded often. However, new recordings of some of his lesser-known operas, like Le Timbre d'argent, La Princesse jaune, and Phryné, have been released recently.

Awards and Reputation

Saint-Saëns received many honors during his life. He was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour in 1867 and was promoted to higher ranks, becoming a Grand Croix in 1913. He also received honors from other countries, including the British Royal Victorian Order in 1902, and honorary doctorates from the universities of Cambridge (1893) and Oxford (1907).

In a poem he wrote in 1890, Saint-Saëns joked that he lacked "decadence" and praised the strong passions of youth, wishing he could still feel them. An English writer in 1910 noted that Saint-Saëns supported young people who wanted to push forward in music, remembering his own youth when he championed new ideas. The composer tried to find a balance between new ideas and traditional forms in his music.

Experts say that while Saint-Saëns's works are very consistent, he didn't create a completely unique musical style. Instead, he protected the French musical tradition from being overwhelmed by Wagner's influence. He also helped create an environment that supported the next generation of French composers.

Since his death, many people who like his music regret that he is mostly known for only a few pieces, like The Carnival of the Animals, the Second Piano Concerto, the Organ Symphony, and Samson et Dalila. Among his many works, some experts point to his Requiem, the Christmas Oratorio, and the Septet for trumpet, piano, and strings as overlooked masterpieces. In 2004, the cellist Steven Isserlis said that Saint-Saëns deserves a festival dedicated to his music because all his cello pieces are interesting and rewarding, and he was an endlessly fascinating person.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Camille Saint-Saëns para niños

In Spanish: Camille Saint-Saëns para niños