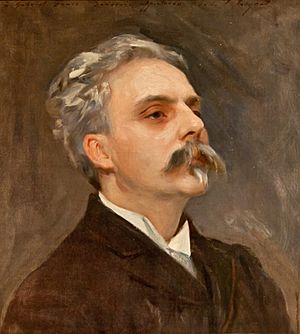

Gabriel Fauré facts for kids

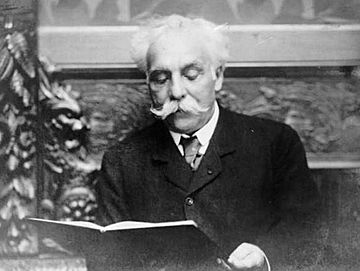

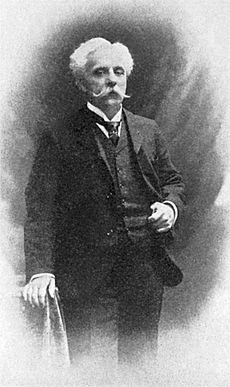

Gabriel Urbain Fauré (born May 12, 1845 – died November 4, 1924) was a famous French composer, organist, pianist, and teacher. He was one of the most important French composers of his time. His unique musical style influenced many composers in the 20th century.

Some of his most well-known pieces include his Pavane, Requiem, Sicilienne, and piano pieces called nocturnes. He also wrote famous songs like "Après un rêve" and "Clair de lune". While his earlier works are often the most popular, Fauré created some of his most admired music later in life. These later pieces had more complex harmonies and melodies.

Fauré grew up in a family that loved culture but wasn't especially musical. His talent for music was clear from a young age. When he was nine, he went to the École Niedermeyer music school in Paris. There, he trained to become a church organist and choirmaster. One of his teachers was Camille Saint-Saëns, who became a close friend for life.

After finishing school in 1865, Fauré worked as an organist and teacher. This left him little time to compose. Later, when he became successful, he held important jobs like organist at the Église de la Madeleine and director of the Paris Conservatoire. Even then, he still needed to escape to the countryside during summer holidays to focus on writing music. By the end of his life, he was seen as the leading French composer. In 1922, a special national tribute was held for him in Paris, led by the president of France. Outside France, his music took longer to become popular, except in Britain, where he had many fans during his lifetime.

Fauré's music is seen as a link between the end of Romanticism and the modern music of the early 20th century. When he was born, Chopin was still composing. By the time Fauré died, jazz and new kinds of atonal music were starting to appear. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians calls him the most advanced composer of his generation in France. It notes that his new ideas in harmony and melody influenced how music was taught for many years. In his last twenty years, Fauré suffered from increasing deafness. His music from this period can be quiet and thoughtful, or sometimes strong and passionate.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Gabriel Fauré was born in Pamiers, a town in the south of France, on May 12, 1845. He was the fifth son and youngest of six children. His family had a long history in that part of France, but by the 1800s, they were not as wealthy as before. Gabriel was the only one of his siblings who showed a talent for music. His brothers became journalists, politicians, or worked in the army or government.

When he was four, Fauré moved back to live with his family after living with a foster mother. His father became the director of a teacher training college near Foix.

An old blind woman, who often listened to Fauré play, told his father about his musical gift. In 1853, a member of the National Assembly heard Fauré play. He suggested that Fauré's father send him to the École Niedermeyer in Paris. After thinking about it for a year, Fauré's father agreed. He took the nine-year-old boy to Paris in October 1854.

Fauré stayed at the school for 11 years with the help of a scholarship. The school life was strict, the rooms were dark, and the food was not great. However, the music lessons were excellent. The school's goal was to train skilled organists and choirmasters, focusing on church music. Fauré learned organ, harmony, counterpoint, fugue, piano, plainsong, and composition.

When the school's founder, Louis Niedermeyer, died in 1861, Camille Saint-Saëns took over the piano lessons. Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré and other students to new music by composers like Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner. Fauré later remembered how Saint-Saëns would play these exciting pieces for them. He felt a deep admiration and gratitude for Saint-Saëns throughout his life.

Saint-Saëns was very happy with Fauré's progress and helped him whenever he could. Their close friendship lasted for sixty years until Saint-Saëns passed away.

Fauré won many awards at the school, including a top prize for his composition Cantique de Jean Racine. This was one of his first choral works that is still performed today. He left the school in July 1865, having excelled in organ, piano, harmony, and composition. He also earned a diploma to be a church music director.

Starting His Career

After leaving school, Fauré became an organist at the Church of Saint-Sauveur in Rennes, France, in January 1866. He also gave many private piano lessons to earn more money. He continued to compose, but none of his works from this time have survived. He found Rennes boring and didn't get along well with the local priest. In 1870, he was asked to resign after showing up to play Mass in his evening clothes, having been out all night.

Soon after, with Saint-Saëns's help, he got a job as assistant organist in Paris. When the Franco-Prussian War started in 1870, Fauré joined the army. He fought in battles to lift the siege of Paris and was awarded a medal.

After the war, Fauré went to Switzerland for a short time, where he taught at the École Niedermeyer, which had moved there temporarily. His first student there was André Messager, who became a lifelong friend. Fauré's music from this period did not directly show the war's troubles. However, some biographers note that his songs from this time, like L'Absent and La Chanson du pêcheur, gained a new, darker feeling.

When Fauré returned to Paris in October 1871, he became choirmaster at the Église Saint-Sulpice. He wrote several church songs and motets for his duties. He often attended musical gatherings hosted by Saint-Saëns and the singer Pauline Viardot.

Fauré was a founding member of the Société Nationale de Musique, created in 1871 to promote new French music. Many of his works were first performed at the society's concerts. He became the society's secretary in 1874.

In 1874, Fauré moved to the Église de la Madeleine, filling in for Saint-Saëns, who was often away on tour. Fauré was known for his improvisations on the organ. However, he preferred the piano and only played the organ for the steady income it provided.

The year 1877 was important for Fauré. In January, his first violin sonata was performed and was a great success. This marked a turning point in his composing career at age 31. In March, he became the chief choirmaster at the Madeleine. In July, he got engaged to Marianne, Pauline Viardot's daughter. Sadly, she broke off the engagement in November 1877. To cheer him up, Saint-Saëns took him to Germany to meet Franz Liszt. This trip made Fauré love foreign travel, which he continued throughout his life.

From 1878, he and Messager traveled to see Wagner operas. They saw many of Wagner's famous works. They even wrote a fun, short piano piece together called Souvenirs de Bayreuth, which made fun of themes from Wagner's Ring cycle. Fauré admired Wagner's music but was one of the few composers of his generation who was not strongly influenced by Wagner's style.

Middle Years and Teaching

In 1883, Fauré married Marie Fremiet, the daughter of a famous sculptor. Their marriage was caring, but Marie preferred to stay home and didn't share Fauré's love for going out. She sometimes felt upset by his frequent absences. Fauré and Marie had two sons. Emmanuel became a well-known biologist, and Philippe became a writer.

To support his family, Fauré spent most of his time working at the Madeleine and giving piano and harmony lessons. His compositions didn't earn him much money because his publisher bought them outright, paying him a small fee for each song. He didn't receive royalties. During this time, he wrote several large works, but he often destroyed them after a few performances, keeping only parts to reuse.

One important work that survived from this period is the Requiem. He started it in 1887 and revised it until its final version in 1901. After its first performance in 1888, the priest at the Madeleine told him, "We don't need these new pieces."

As a young man, Fauré was very cheerful. But from his thirties, he suffered from periods of sadness, possibly due to his broken engagement and slow success as a composer. In 1890, a big project to write an opera fell apart. This made Fauré so sad that his friends worried about his health. A good friend, Winnaretta de Scey-Montbéliard, invited him to Venice. There, he recovered and started composing again, writing his first Mélodies de Venise.

Around this time, Fauré's personal life inspired a new burst of creativity in his music, seen in the song cycle La bonne chanson. He also wrote the Dolly Suite for piano duet between 1894 and 1897, dedicating it to a young girl named Hélène, known as "Dolly."

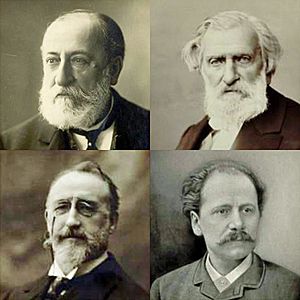

In the 1890s, Fauré's career improved. When a composition professor at the Paris Conservatoire died in 1892, Saint-Saëns encouraged Fauré to apply for the job. The Conservatoire leaders thought Fauré was too modern. The head, Ambroise Thomas, said, "Fauré? Never! If he's appointed, I resign." However, Fauré was appointed as an inspector of music conservatories in the French provinces. He didn't like the constant travel, but it gave him a steady income.

In 1896, Ambroise Thomas died, and Théodore Dubois became the new head of the Conservatoire. Fauré then took over Dubois's old job as chief organist of the Madeleine. Dubois's move also meant that Massenet, another composition professor, resigned in anger. Fauré was then appointed to Massenet's professorship.

Fauré taught many young composers who later became famous, including Maurice Ravel, Florent Schmitt, Charles Koechlin, and Nadia Boulanger. He believed his students needed strong basic skills. His main role was to help them use these skills to develop their own unique talents. Ravel always remembered Fauré's open-mindedness as a teacher. Fauré once told Ravel he might have been wrong about his String Quartet and asked to see the manuscript again.

Fauré's works from the late 1800s include music for the play Pelléas et Mélisande (1898) and Prométhée, a large-scale work for outdoor performance. Prométhée was a great success when it premiered in 1900.

From 1903 to 1921, Fauré regularly wrote music reviews for a newspaper called Le Figaro. He found this role difficult because he naturally preferred to focus on the good parts of a work.

Leading the Paris Conservatoire

In 1905, a controversy happened over France's top music prize, the Prix de Rome. Fauré's student Ravel was unfairly eliminated from the competition. Many believed that old-fashioned people at the Conservatoire were to blame. The director, Dubois, retired early because of the criticism.

With the support of the French government, Fauré was appointed as the new director. He made big changes to the school's rules and what was taught. He brought in outside judges for admissions and exams, which angered some teachers who used to favor their private students. Fauré was even called "Robespierre" by those who disliked his changes. He modernized the Conservatoire, allowing students to study a wider range of music, from old Renaissance music to works by Debussy.

Fauré's new job improved his financial situation. However, running the Conservatoire left him with little time to compose. Every year, as soon as the school year ended in July, he would leave Paris. He spent two months in a hotel, often by a Swiss lake, to focus on writing music. Works from this period include his opera Pénélope (1913) and some of his most famous later songs and piano pieces.

In 1909, Fauré was elected to the Institut de France, a prestigious French academy. His father-in-law and Saint-Saëns, who were already members, strongly supported him. In the same year, a group of young composers, including Ravel, formed a new society called the Société musicale indépendante because the older society had become too traditional. Fauré became the president of this new society, but he also remained a member of the old one. His only goal was to support new music. In 1911, he oversaw the Conservatoire's move to a new building.

During this time, Fauré began to have serious hearing problems. Not only was he going deaf, but sounds became distorted, making high and low notes sound painfully out of tune to him.

Around the early 1900s, Fauré's music became more popular in Britain, and somewhat in Germany, Spain, and Russia. He visited England often. In 1908, an invitation to play at Buckingham Palace opened many doors for him in London. He met Edward Elgar, another famous composer, who admired Fauré greatly. Composers from other countries also loved Fauré's music, including Tchaikovsky and Richard Strauss. The young American composer Aaron Copland was also a devoted admirer in Fauré's later years.

When the First World War started, Fauré was almost stuck in Germany, where he had gone to compose. He managed to get to Switzerland and then back to Paris. He stayed in France for the whole war. When some French musicians tried to boycott German music, Fauré disagreed. He believed music was a language that belonged to everyone, not just one nation.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1920, at age 75, Fauré retired from the Conservatoire due to his increasing deafness and weakness. That year, he received the Grand-Croix of the Légion d'honneur, a very high honor for a musician. In 1922, the French president, Alexandre Millerand, led a public tribute to Fauré at the Sorbonne. It was a moving event: Fauré was at a concert of his own works but could not hear a single note. He sat thoughtfully, grateful and content.

Fauré's health was poor in his last years, partly due to heavy smoking. Despite this, he remained open to young composers. In his final months, Fauré worked hard to complete his String Quartet. He had refused to write one for many years, thinking it was too difficult, especially after Beethoven's famous quartets. He finished it on September 11, 1924, less than two months before he died. The quartet was performed after his death. He declined an offer to hear it privately because his hearing was so bad that music sounded horribly distorted.

Gabriel Fauré died in Paris from pneumonia on November 4, 1924, at age 79. He had a state funeral at the Église de la Madeleine and is buried in the Passy Cemetery in Paris.

After Fauré's death, the Conservatoire became less open to new music. Fauré's own style was seen as the limit of modern music. However, later generations of students looked to other composers for inspiration.

In 1945, a music expert named Leslie Orrey wrote that Fauré was "the master par excellence of French music, the perfect mirror of our musical genius."

Music

The composer Aaron Copland noted that while Fauré's works can be divided into early, middle, and late periods, his style didn't change as dramatically as some other composers'. Copland found hints of Fauré's later style even in his earliest pieces, and traces of his early charm in his old age. He said that Fauré's themes, harmonies, and forms stayed mostly the same but became "more fresh, more personal, more profound" with each new work. When Fauré was born, Chopin was still composing, and he influenced Fauré's early music. In his later years, Fauré developed techniques that hinted at the atonal music of Schoenberg and even jazz.

Fauré was influenced by Chopin, Mozart, and Schumann, especially in his early work. He learned restraint and beauty from Mozart, and long melodies from Chopin. From Schumann, he learned to use surprising and delightful musical moments. His music was built on a strong understanding of harmony, which he learned at the École Niedermeyer. He used mild, unresolved discords and colorful effects, which were new ideas that influenced Impressionist composers.

Unlike his harmony and melody, which were quite daring for his time, Fauré's rhythms were often subtle and repeated. They created a smooth flow, though he sometimes used quiet syncopations, similar to those found in Brahms's music. Some critics have even called him "the Brahms of France."

Some critics believe Fauré's later works don't have the easy charm of his earlier music. They describe his later style as more serious, with many enharmonic shifts, making it sound like several keys are being used at once.

Vocal Music

Fauré is considered one of the greatest composers of French art songs, called mélodies. Ravel once said that Fauré saved French music from being dominated by German songs.

Copland felt that Fauré's early songs, written in the 1860s and 1870s, didn't fully show his unique style, except for a few like "Après un rêve". However, his mature songs from the next two decades, like "Les berceaux" and "Clair de lune", are considered true examples of "the real Fauré." Fauré also composed several song cycles, which are groups of songs linked by a theme. For example, Cinq mélodies "de Venise" (1891) used musical themes that appeared throughout the cycle.

The Requiem, first performed in 1888, was not written for a specific person. Fauré said he composed it "for the pleasure of it." It is often called "a lullaby of death" because of its gentle and peaceful mood. Fauré changed the Requiem over the years, and today there are different versions performed, from small groups to full orchestras.

Fauré's operas are not performed very often. Prométhée has only been performed a few times in over a century. Copland found Pénélope (1913) to be a fascinating work and one of the best operas written after Wagner. However, he noted that the music is "distinctly non-theatrical," meaning it doesn't always work well on stage. When the opera has been performed, critics usually praise the beautiful music but have mixed opinions about its dramatic impact.

Piano Works

Fauré's main piano works include thirteen nocturnes, thirteen barcarolles, six impromptus, and four valses-caprices. These pieces were written throughout his career, showing how his style changed from simple youthful charm to a more thoughtful, sometimes passionate, and mysterious style in his later years. Other notable piano pieces include Romances sans paroles and the Ballade in F-sharp major. For piano duet, Fauré composed the Dolly Suite and, with his friend André Messager, a playful parody of Wagner called Souvenirs de Bayreuth.

Fauré's piano works often use arpeggiated figures, where the melody is shared between both hands. These techniques can make them challenging for some pianists. Even a great pianist like Liszt found Fauré's music hard to play. His early piano works were clearly influenced by Chopin. However, Schumann was an even greater influence, as Fauré loved his piano music more than any other. The critic Bryce Morrison noted that pianists often prefer to play Fauré's charming earlier piano works rather than his later ones. These later works express "such private passion and isolation" that they can make listeners feel uneasy. Fauré valued clear, classical style over flashy virtuosity in his piano music.

Orchestral and Chamber Works

Fauré was not very interested in orchestration, which is the art of arranging music for an orchestra. Sometimes, he even asked his former students, like Jean Roger-Ducasse and Charles Koechlin, to orchestrate his works. Fauré's orchestral style was generally simple. He believed that too many flashy instrument combinations could hide a lack of real musical ideas. He told his students that they should be able to orchestrate without using instruments like glockenspiels or xylophones.

Fauré's most famous orchestral works are the suites Masques et bergamasques, Dolly, and Pelléas et Mélisande. The Pelléas et Mélisande suite was based on music he wrote for a play.

In chamber music, his two piano quartets, especially the one in C minor, are among his best-known works. His other chamber music includes two piano quintets, two cello sonatas, two violin sonatas, a piano trio, and a string quartet. Copland considered the second quintet to be Fauré's masterpiece, calling it "extremely classic." Fauré's last work, the String Quartet, has been described as a deep and spiritual piece, with themes that seem to reach for the sky.

Recordings

Fauré made piano rolls of his music between 1905 and 1913. Many recordings of his music were made between 1898 and 1905, mostly of songs and short chamber pieces. By the 1920s, more of his popular songs were recorded. In the 1930s, famous performers like Jacques Thibaud and Alfred Cortot recorded Fauré's pieces.

By the 1940s, more of Fauré's works were available on records. In the 1950s, his music started appearing more frequently. Today, there is a large collection of Fauré's music available on CDs, performed by musicians from France and other countries. Many modern recordings of Fauré's music have won awards.

His major orchestral works have been recorded by conductors like Michel Plasson and Yan Pascal Tortelier. Fauré's main chamber works have all been recorded by various musicians. The complete piano works have been recorded by Kathryn Stott and Paul Crossley. All of Fauré's songs have been recorded for CD, including a complete set with many soloists. His Requiem and shorter choral works are also widely available. His opera Pénélope has been recorded twice.

Modern Assessment

Fauré's biographer, Jean-Michel Nectoux, writes in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians that Fauré is widely seen as the greatest master of French song. He also states that Fauré's chamber works are among his most important contributions to music.

See also

In Spanish: Gabriel Fauré para niños

In Spanish: Gabriel Fauré para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |