Canadian Indigenous law facts for kids

Indigenous law in Canada means the special legal traditions, customs, and ways of life of Indigenous peoples and groups. It's different from Canadian Aboriginal law, which is about the rights given to Indigenous peoples by the Canadian government.

Canada is the traditional home of over 900 different Indigenous groups. Each group has its own unique legal traditions. For example, the Cree, Blackfoot, Mi'kmaq, and many other First Nations, along with the Inuit and Métis, use their own laws every day. These laws help them make agreements, work with governments, manage nature, and handle family matters. Most groups keep their laws alive through traditional leaders, alongside elected officials and federal laws. These ancient laws are passed down through stories, actions, and the wisdom of elders and law-keepers. This is similar to how many other legal systems, like common laws, have grown over time.

While many Indigenous legal traditions were not written down, they each have different sets of laws. Many laws come from stories, which might be linked to writings or markings on the land, like petroglyphs (rock carvings) or pictographs (rock paintings). For example, the way Inuit Nunangat is governed is quite different from its neighbour Denendeh. And Denendeh's diverse Dene Laws are very different from the laws of the Lingít Aaní or Gitx̱san Lax̱yip. One thing many Indigenous legal traditions share is the use of clans, like the Anishinaabek's doodeman.

Understanding Key Terms

Indigenous Law vs. Aboriginal Law

Indigenous law refers to the legal systems created and used by Indigenous peoples themselves. These systems include laws and ways of solving problems that Indigenous groups developed to manage their relationships, use their natural resources, and settle disagreements. Indigenous law comes from many different sources and traditions.

Canadian Aboriginal law, on the other hand, is the part of Canadian law that deals with the Canadian Government's relationship with Indigenous peoples (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit). The Canadian Constitution gives the federal government the power to make laws about Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous Self-Government

Indigenous self-government in Canada means that Indigenous groups have the right to govern themselves. This includes making their own laws and decisions about their communities, lands, and cultures. It's about Indigenous peoples having control over their own lives and futures.

Indigenous Legal Traditions Across Canada

Anishinaabe Law

Anishinaabe laws come from many stories that help explain how to live as a community and as an individual. These stories include tales of Nanabozho and other beings. They teach important lessons and practical ways of life. Historically, Anishinaabe Law has worked with other nations' legal systems, like the Gdoo-naaganinaa (Dish With One Spoon) Treaty with the Haudenosaunee. The Atikameksheng Anishinawbek people call "law" Naaknigewin.

Atikamekw Law

The Atikamekw Nation, from their homeland Nitaskinan, has a strong connection to their language and traditional legal system, called irakonikewin or orakonikewin. There are differences between Atikamekw law and Canadian laws, especially regarding adoption, which they call opikihawasowin. Efforts are being made to bring these legal systems closer together.

Blackfoot Law

The Blackfoot word for "law-making" is Akak′stiman.

Dene Law

Dene law includes the many legal traditions of the Dene homelands, known as Denendeh. This area is home to nations like the Gwich'in, Hän, Kaska, Tutchone, Sahtu, Dane-zaa, Dene Thá, Tłı̨chǫ, and Dënësųłı̨né. Dene laws are believed to have been created by cultural heroes like Yamoria and Yamozha, often called the Great Lawmaker(s).

Dene legal ideas are generally based on equality, sharing, and helping each other. They also believe that humans and nonhuman life (like animals, trees, and mountains) are all connected. Stories often show Dene people and animals working together to find solutions that benefit everyone. This creates a special relationship where animals share their gifts, and humans show respect by protecting nature and being thankful. For example, Dene law says that people traveling across the land should offer gifts to waterways and landforms.

Differences between English law and Dene law have sometimes caused problems. For instance, there are different ideas about how to protect animals. English law might suggest hunting only male caribou to help the herd grow. But Dene law sees this as harmful, like losing all the elder men in a community. Dene people believe that animals choose to give themselves to hunters, which is different from the idea that humans must control and conserve other species.

Since there are many Dene languages and cultures, their legal systems have different names. For example, Tłı̨chǫ call Dene law Dǫ Nàowoòdeè.

Eeyou/Eenou Law

The modern legal system of Eeyou Istchee has grown from its interactions with the Canadian government and Québec. It also comes from the historical, traditional Eeyou or Eenou Eedouwin (the Eeyou/Eenou way of doing things).

Gitanyow Law

The legal system of the Gitanyow people is called Gitanyow Ayookxw.

Gitx̱san Law

The Gitx̱san people's laws are known as Ayookim Gitx̱san or Ayook.

The most important part of Gitx̱san society is the matrilineal "Houses" or wilphl Gitx̱san (also called "Huwilp"). Each House belongs to one of four clans: Lax̱gibuu (Wolf), Lax Seel (Raven/Frog), Giskaast (Fireweed), and Lax Skiik (Eagle). Gitx̱san authority, or Dax̱gyat, comes from these Houses and their connection to their territories, called Lax̱yip. Each Huwilp has clear rights to its land, which are known through special inheritances called gwalax̱ yee’nst. These inheritances include not only family and land but also things like potlatch names, oral histories (adaawx), songs, and spirit songs.

The Ayookim Gitx̱san connects all of Gitx̱san society. It guides how Houses handle inheritance, marriage, adoption, land use, and solving problems. The adaawx (oral histories) are the backbone of the Ayookw. They provide proof of land ownership and how society is organized. Like many other coastal First Nations, the central political gathering is the potlatch, or liligit. The "Wilp Li’iliget is the Feast House and is seen as the Gitx̱san Parliament Building."

Today, the Gitx̱san Nation has faced challenges with different government structures. After an important court case in 1997 (Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa case), the Gitx̱san Houses came together to form the Gitx̱san Huwilp Government. Although their oral histories (adaawk) were not fully accepted as evidence in that specific case, the court later made it clearer how such evidence can be used. This is helping to strengthen Gitx̱san Ayookim and governance.

Haisla Law

Haisla Nuuyum, or the Haisla way of life and laws, guides how people interact within Haisla Country and with neighboring groups. The Nuyuum supports both traditional and modern leadership, like the Chief and Council system. It helps guide the nation's responsibilities.

Haudenosaunee Law

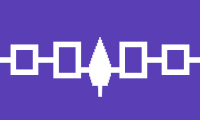

The Haudenosaunee (Six Nations of the Longhouse) formed a confederacy around 1142 C.E. by creating the Great Law of Peace (or Kaianere’kó:wa in Kanienʼkéha). This is one of the oldest continuously working representative democracies in the world. The original five nations (Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, and Mohawk) united under this law. Their core legal framework is passed down orally through special wampum belts and is symbolized by the Tree of Peace, the eastern white pine.

The laws are shared through symbolic wampum belts and have 117 articles. Each year, the story of the confederation is retold. This story describes how the Great Peacemaker, Jigonhsasee, and Hiawatha brought peace to Haudenosaunee Country. They created government structures and legal systems to unite families. Nations are seen as elder and younger brothers. The Peacemaker explained that this new structure would be like "the longhouse in which there are many hearths, one for each family, yet all live as one household under one chief mother. They shall have one mind and live under one law."

Inuit Law

Traditional Inuit justice understands that everything is connected. Leaders and Elders do not see themselves as simply enforcing rules. Instead, every person helps the community work well. The word for Inuit Law in Inuktitut is ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦ Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, which means "that which has long been known by Inuit."

There are three main parts to Inuit law:

- tirigusuusiit: things to avoid

- maligait: things to follow

- piqujait: things to do

If these rules were not followed, an angakkuq (or medicine person) might need to help. Breaking these laws was thought to cause bad luck, like bad weather or unsuccessful hunts. To find out why misfortune happened, the angakkuq would go on a spirit journey. When they returned, they would question people. Often, people would confess, and this confession alone could solve the problem, or some actions might be needed to make things right.

Bringing Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) and Canadian Law together is an ongoing process. For example, the Nunavut Court of Justice is a unique court in Canada. It travels to communities regularly. There are also programs that use traditional healing circles.

Ktunaxa Law

The main idea of Ktunaxa law (or Ɂaknumu¢tiŧiŧ) is that the Ktunaxa people came from their traditional land, Ktunaxa ɁamakɁis. They are the keepers of this land and must care for and respect it, along with all living and nonliving things on it. Ɂaknumu¢tiŧiŧ means that Ktunaxa people must protect the land and not use too much from it. This helps keep everything balanced, as they understand that all things are connected and the land provides what they need to survive.

Kwakwaka'wakw Law

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw legal system, from their homeland Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw A̱wi'nagwis, is still managed through the potlatch ceremony. This is true even though the Potlatch Ban lasted from 1884 to 1951. Like many other coastal nations, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw and its communities have many laws about the rights to "treasures." These include songs, dances, coppers (special copper shields), regalia (ceremonial clothing), names, crests, stories, and knowledge.

Unlike European legal systems, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw law sees society and individual rights differently. Stories, songs, dances, and knowledge are passed down through specific potlatch rituals. Disagreements are settled through ceremonies, often held in big houses, led by knowledgeable community leaders or Elders. Because of this, ideas about intellectual property and property law are very different from Canadian legal systems. The Canadian government is working to bring its laws and past policies in line with the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Nation.

Métis Law

La lway michif, or Métis law, is a mix of legal traditions. It combines ideas from the Indigenous nations of the prairies, European Canadians who settled in the Métis homeland (Michif Piyii), and Christianity. Métis culture is an oral culture, so many rules about family and community are passed down by speaking, not writing.

The main part of Métis law comes from inherited stories, like those of Ti-Jean, Wisahkecahk, and Nanbush. It focuses on the family, and decisions are made by the whole community in an assembly. Elders act as mediators and advisors. Ceremonies are also very important. Justice is based on individual and community rights, and decisions must be made with respect and trust. Solving problems is done in a way that avoids conflict, and decisions are made by everyone agreeing.

Historically, the Métis legal system included a general council that oversaw a policing group called la garde.

Mi'kmaw Law

Mi'kma'ki is home to Netukulimk. This means "using the natural gifts from the Creator for the well-being of the individual and community." A key part of Netukulimk is making sure the community has enough food and economic well-being without harming the environment. Within Netukulimk, Mi'kmaw law helps keep Mi'kmaw families, communities, and society strong. This way of thinking sees all life as connected. It describes the rights and responsibilities of the Mi’kmaq with their families, communities, nation, and the environment.

Nêhiyaw Law

In the nêhiyaw language, "Cree laws" translates as ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐤ ᐃᐧᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᓇ nêhiyaw wiyasowêwina. However, a better term for Cree (especially Plains Cree) law is Wahkohtowin (ᐋᐧᐦᑰᐦᑐᐃᐧᐣ). This word means both kinship (family connections) and the rules of conduct that come from a person's role in their community.

Secwépemc Law

In Secwepemcúl'ecw, the Shuswap people still follow yirí7 re stsq’ey’s-kucw, which means "our laws and customs." Secwépemc law, or Stsq̓ey, is understood through the stseptékwll (ancient oral histories). These histories say that the laws were given to the Secwépemc by Sk’elép (Coyote). Stsq'ey guides the nation through three main laws:

- Secwepemc law of sovereignty (including the power to make treaties);

- Secwepemc law that defines rights and access to resources; and

- Secwepemc laws of social and environmental responsibility (caretakership).

Syilx Law

Born from iʔ syilx iʔ temxʷulaʔxʷs, or Okanagan Country, Syilx law is defined through captikwł. This is "a collection of teachings about Syilx Okanagan laws, customs, values, and principles." Together, these define and explain Syilx Okanagan rights and responsibilities to the land and their culture. The Syilx Nation uses ankc’xʷ̌iplaʔtntət uɬ yʕat iʔ ks səctxət̕stim ("our laws and responsibilities") as its main framework. From this come Syilx values, citizenship, ways to solve problems, government authority, rights, and responsibilities. These are especially important for their connection to the tmixʷ, tmxʷulaxʷ, and siwłkʷ (all living beings, the land, and the waters). The Syilx Okanagan Nation Alliance is currently working to rebuild the nation and create a modern constitution.

Tŝilhqot'in Law

The name for Tŝilhqot'in law is Dechen Ts’edilhtan.

Wet'suwet'en Law

After disagreements in Wet'suwet'en Country in British Columbia, the BC and Canadian governments signed an agreement with the Wet'suwet'en Nation's hereditary chiefs in May 2020. The agreement starts by saying:

- "Canada and B.C. recognize that Wet’suwet’en rights and title are held by the Wet’suwet’en houses under their system of governance."

- "Canada and B.C. recognize Wet’suwet’en aboriginal rights and title throughout the Yintah [traditional territory]."

This agreement confirms Anak Nu'at'en (also spelled Inuk Nuatden) as the Wet'suwet'en legal system. The Wet'suwet'en system of governance is closely linked to their hereditary chiefs. Clan structures and governing chiefs are, in turn, deeply connected to Yin'tah, their lands.

W̱SÁNEĆ Law

Coming from the land, or TEṈEW̱, the W̱SÁNEĆ term SKÁLS means both "law" and "beliefs."

See also

In Spanish: Derecho indígena canadiense para niños

In Spanish: Derecho indígena canadiense para niños

- Aboriginal land title in Canada

- The Canadian Crown and Indigenous peoples

- Indian Act

- Indigenous court (Canada)

- Numbered Treaties

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |