Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cinder Cone |

|

|---|---|

Cinder Cone is a 748-foot (213 m) high cone of loose scoria

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 6,896 ft (2,102 m) NGVD 29 |

| Geography | |

| Location | Lassen and Shasta counties, California, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Prospect Peak |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Extinct Cinder cone |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 1666 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Trail hike |

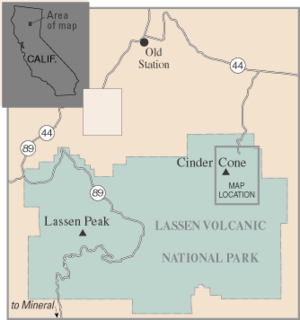

Cinder Cone is a special type of volcano called a cinder cone. It's located in Lassen Volcanic National Park in the United States. This volcano is about 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lassen Peak. From Cinder Cone, you can get amazing views of other mountains like Brokeoff Mountain and Chaos Crags.

The cone grew to be about 750 feet (229 m) tall. It spread volcanic ash over a large area, about 30 square miles (78 km2). Like many cinder cones, it stopped erupting after several basalt lava flows burst from its base. These flows are known as the Fantastic Lava Beds.

The Fantastic Lava Beds spread out, blocking creeks. This created two lakes: Snag Lake to the south and Butte Lake to the north. Water from Snag Lake seeps through the lava beds to feed Butte Lake. The Nobles Emigrant Trail goes around Snag Lake and follows the edge of these lava beds.

For a long time, people argued about how old Cinder Cone was. Some thought it was only a few decades old in the 1870s. Later, people believed it formed around 1700 or during eruptions that ended in 1851. But recent studies by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientists have shown that Cinder Cone formed during two eruptions in the 1650s.

Contents

Where is Cinder Cone?

Cinder Cone is in Lassen and Shasta counties in Northern California. It's part of the Lassen Volcanic National Park. The volcano is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southwest of Butte Lake. It's also 2.2 miles (3.5 km) southeast of Prospect Peak. Sometimes, people call it Black Butte or Cinder Butte.

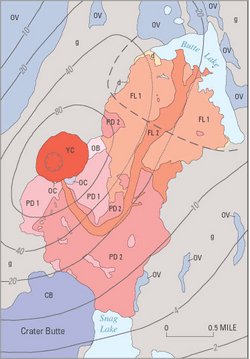

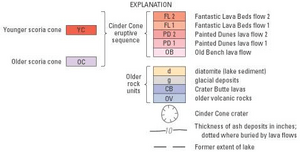

Nearby Snag Lake was formed by lava flows called the Painted Dunes. These flows blocked Grassy Creek, which gets water from the national park's central area. Water from Snag Lake then flows into Butte Lake, which is about 2 miles (3.2 km) north. Butte Lake is just a small part of a much bigger lake that was filled with lava during Cinder Cone's eruptions.

What is Cinder Cone like?

Cinder Cone is a 700-foot (213 m) tall volcanic cone made of loose scoria. It's the youngest volcano of its kind in the Lassen area. Around it, you can see block lava flows with no plants growing on them. At the top, it has two round craters, one inside the other. The larger crater is about 1,050 feet (320 m) wide, and the smaller one is about 590 feet (180 m) wide.

Cinder Cone is made of five different basaltic andesite and andesite lava flows. It also has two smaller scoria cones. Cinder cone volcanoes usually erupt only once in their lifetime. These eruptions often throw out tephra (volcanic rock fragments). They can also produce lava flows, which usually come from vents at the base of the volcano, not the top.

The top of Cinder Cone has a crater with a double rim. This probably happened during two different parts of the same eruption. The cone also left a wide layer of volcanic ash that can be found 8 to 10 miles (13 to 16 km) away. You can see blocks of red, hardened scoria in the Painted Dunes lava flows. These are pieces of an older cone that were carried away by the hot lava.

When Cinder Cone formed, the melted rock (magma) feeding the eruption changed. It started as basaltic andesite, then became andesite, and then went back to basaltic andesite with more titanium. These rocks look similar, even though their chemical makeup is different. They are dark, fine-grained rocks with small crystals of olivine, plagioclase, and quartz.

The earliest volcanic material at Cinder Cone has less titanium. This includes the older scoria cone, the Old Bench flow, the two Painted Dunes flows, and the bottom part of the ash layer. The second group of materials erupted later and has more titanium. This includes the younger scoria cone, the top part of the ash layer, and the two Fantastic Lava Beds flows. The whole eruption of Cinder Cone happened over several months.

The Fantastic Lava Beds have unusual quartz crystal pieces. Geologists think these were picked up from the surrounding rocks by the lava as it moved to the surface.

How We Learned About Cinder Cone's History

Early Studies of the Volcano

The first geologist to study Cinder Cone was Joseph Diller. He was one of the first scientists from the USGS to study volcanoes. Diller took careful notes and talked to many Native Americans and settlers in the Lassen area in 1850. No one he spoke to remembered any volcanic activity there.

He knew about an "emigrant road" (the Nobles Emigrant Trail) that settlers used in the early 1850s. This road passed close to Cinder Cone. Diller interviewed people who used the trail in 1853. They said that a large willow bush near the top of Cinder Cone was already there and had not been destroyed by any eruption. This bush is still alive today and hasn't changed much.

Because the willow was already grown in 1853, Diller believed an eruption could not have happened in the winter of 1850. He also noticed that trees growing in the volcanic ash from the cone were about 200 years old. The oldest trees on the lava flows were about 150 years old. Diller thought there were two eruption periods, each producing lava flows. He concluded that the explosive eruption that created Cinder Cone and the ash happened long before 1800. He guessed it was between 1675 and 1700. He thought the younger, quieter eruption happened before 1840.

In 1907, Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak became national monuments. Cinder Cone's name was officially recognized in 1927. In the 1930s, another USGS volcanologist, R. H. Finch, tried to improve on Diller's work. Finch thought there were at least five separate lava flows. He also believed the youngest lava flow happened in 1851, based on old stories. He thought there were at least two big explosive eruptions. Using these ideas and tree-ring measurements, Finch suggested a complex timeline for Cinder Cone that lasted almost 300 years. He thought the two explosive eruptions happened in 1567 and 1666. He also believed the five lava flows happened in 1567, 1666, 1720, 1785, and 1851.

New Discoveries About Cinder Cone

After Finch's work in 1937, not much new research was done on volcanoes in the Lassen area. But this changed after the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington. The USGS started looking at the risks from other active volcanoes, including those in Lassen Volcanic National Park. Since then, USGS scientists have been working with the National Park Service to better understand volcanic dangers in the Lassen area. As part of this, they re-examined Cinder Cone's history.

New studies have shown that all the eruptions at Cinder Cone happened as one continuous event. The direction of Earth's magnetic field in the 1850s is known. It's different from the magnetic direction recorded in Cinder Cone's lava flows. This means the lava flows could not have erupted in 1850 or 1851. Also, all the lava flows at Cinder Cone have the same magnetic direction. This tells us they must have erupted within a short time, less than 50 years.

While magnetic evidence ruled out the 1850s, it didn't give an exact age. So, USGS scientists used carbon-14 dating. They measured carbon-14 levels in wood from trees killed by the eruption. This gave them a date between 1630 and 1670. This date also matches the magnetic evidence. The eruptions that created Cinder Cone were complex and are still being studied. However, the new research proves that the stories of an eruption in the early 1850s were wrong. It confirms Diller's idea that Cinder Cone erupted in the late 1600s. It also suggests that Finch's 1666 tree-ring date for his "second" eruption might actually be the date for the entire eruption sequence.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |