Codex Calixtinus facts for kids

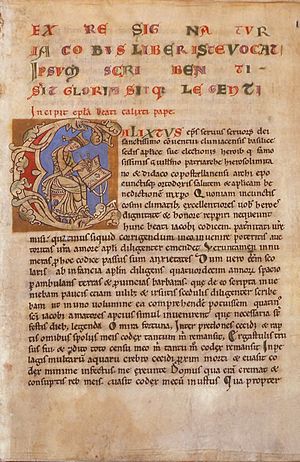

The Codex Calixtinus (pronounced Koh-dex Kah-lix-TEE-nus) is a very old handwritten book from the 12th century. It's also known as the Book of Saint James. Even though it's linked to Pope Calixtus II, many experts believe a French scholar named Aymeric Picaud was the main person who put it together. This important book was likely finished between 1138 and 1145.

The Codex Calixtinus was created to be a helpful guide for pilgrims. These pilgrims were people traveling along the Way of Saint James (or Camino de Santiago) to visit the tomb of Saint James the Great. His tomb is located in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain. The book contains many different things, like sermons, stories of miracles, and special prayers for Saint James. It also has musical pieces, descriptions of the pilgrimage route, information about artworks along the way, and details about the local people's customs.

Contents

History of the Codex

The Codex Calixtinus was put together before 1173, most likely in the late 1130s or early 1140s. Many historians believe the French scholar Aymeric Picaud was responsible for gathering its contents.

Each of the five books inside the Codex starts with a letter. These letters claim to be from Pope Calixtus II, who died in 1124. An appendix also includes a letter from Pope Innocent II, who died in 1143. This letter presents the finished work to the church in Santiago. Stories of miracles in Book II happened between 1080 and 1135. This helps us know the book was likely completed between 1135 and 1173, most probably in the 1140s.

The Codex Calixtinus is seen as the first complete version of the Book of Saint James. Because of this, people often use the names Liber sancti Jacobi and Codex Calixtinus to mean the same thing. One interesting idea is that the book was written in a simple Latin style. Some think it might have even been used as a kind of grammar book.

The oldest copy of the Codex was made in 1173 by a monk named Arnaldo de Monte. This copy is known as The Ripoll, named after the monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll in Catalonia. Many other copies of the book were made later.

The Codex Calixtinus was kept safe in the archives of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela for a long time. It was rediscovered there in 1886 by a scholar named Padre Fidel Fita. The first modern version of the text was prepared in 1932 and published in 1944.

Theft and Recovery

The book was stolen from its secure case in the cathedral's archives on July 3, 2011. News reports at the time suggested the theft might have been to embarrass the cathedral or to settle a personal disagreement.

Luckily, on July 4, 2012, the Codex was found! It was in the garage of a former employee of the Cathedral. This former employee was believed to be the main person behind the theft. He and three family members were questioned until one of them told police where the book was hidden. Other valuable items stolen from the Cathedral were also found at the former employee's home. The Codex looked to be in perfect condition.

In February 2015, the former cathedral employee was found guilty of stealing the Codex. He was also convicted of stealing a large amount of money from collection boxes. He was sentenced to ten years in prison.

What's Inside the Codex?

The copy of the Codex Calixtinus kept in Santiago de Compostela has five main parts, called "books," and two extra sections. It has 225 pages, each printed on both sides. The pages were made smaller during a restoration in 1966. Most pages have one column of 34 lines of text. Book IV was removed in 1609, possibly by accident, theft, or by order of King Philip III. It was put back during the restoration.

The book starts with a letter from someone who says they are Pope Calixtus II. This letter explains how he gathered many stories about the good deeds of Saint James. He also describes how the book survived dangers like fire and floods. The letter is addressed to the church in Cluny and to Diego, the archbishop of Compostela.

Book I: Book of the Liturgies

Book I is the largest part of the Codex, making up almost half of it. It contains sermons and speeches about Saint James. It also includes two descriptions of how he died as a martyr and official prayers for his worship. This book is considered the heart of the Codex because of its size and the spiritual information it provides about the pilgrimage. The Veneranda Dies sermon is the longest work in this book. It was likely part of the celebrations for Saint James's feast day (July 25). It remembers his life, death, and how his remains were moved to the church in Compostela. It also talks about the journey to Compostela in both physical and spiritual ways.

Book II: Book of the Miracles

Book II tells about 22 miracles that people believed Saint James performed. These miracles happened across Europe, both during his life and after his death. The people who received or saw these miracles were often pilgrims.

Book III: Moving the Body to Santiago

Book III is the shortest of the five books. It describes how Saint James's body was moved from Jerusalem to his tomb in Galicia. It also explains the tradition of early pilgrims collecting sea shells as souvenirs from the Galician coast. The scallop shell is now a well-known symbol for Saint James and the pilgrimage.

Book IV: The Story of Charlemagne and Roland

Book IV is often called Pseudo-Turpin because it was thought to be written by Archbishop Turpin of Reims. However, it was actually written by an unknown author in the 12th century. This book tells the story of Charlemagne coming to Spain. It describes his defeat at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass and the death of the knight Roland. It also explains how Saint James appeared to Charlemagne in a dream. Saint James urged him to free his tomb from the Moors and showed him the way by following the Milky Way. This connection led to the Milky Way sometimes being called Camino de Santiago in Spain.

This book was very popular and copied many times. It tells the legend of Santiago Matamoros or 'St. James the Moorslayer'. Scholars believe it was an early form of propaganda used by the Catholic Church. The goal was to encourage people to join the military Order of Santiago. This Order was created to help protect church interests in northern Spain from Moorish invaders. In later years, this legend became a bit uncomfortable for some because it showed Saint James as a fierce fighter centuries after his death. King Philip III even ordered Book IV to be removed from the Codex for a while, and it was circulated as a separate book.

Today, along the Way of St. James in northern Spain, many churches and cathedrals still have statues and chapels honoring 'Saint James the Moorslayer'. This legend now has cultural and historical meaning in northern Spain, separate from its original purpose by the Catholic Church.

Book V: A Guide for the Traveller

Book V is full of helpful tips for pilgrims. It tells them where to stop, which relics to see, and which holy places to visit. It also warns them about bad food and scams. The author even points out other churches that falsely claimed to have relics of Saint James. This book gives us a great look into the life of a 12th-century pilgrim. It also describes the city of Santiago de Compostela and its cathedral. Book V became very popular and is often called the first tourist's guide book. For scholars studying the Basque language, this book is very important. It contains some of the earliest Basque words and phrases from after the Roman period.

In 1993, UNESCO added the Spanish part of the pilgrimage route to its World Heritage List. They described it as showing "the power of the Christian faith among people of all social classes." The French section joined the list in 1998.

Music in the Codex

Three parts of the Codex Calixtinus include music: Book I, Appendix I, and Appendix II. These musical sections are very interesting to musicologists because they contain early examples of polyphony. Polyphony is a style of music where multiple independent melodies are played at the same time. The Codex has the first known piece written for three voices, called Congaudeant catholici (Let all Catholics rejoice together). Modern recordings of this music are available today.

See also

In Spanish: Codex Calixtinus para niños

In Spanish: Codex Calixtinus para niños

- List of codices

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |