Confederate Memorial (Arlington National Cemetery) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Confederate Memorial |

|

|---|---|

| United States | |

The Confederate Memorial in 2011

|

|

| For Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines of the Confederate States of America who died in the American Civil War | |

| Unveiled | June 4, 1914 |

| Location | 38°52′34″N 77°04′38″W / 38.876117°N 77.077277°W near |

| Designed by | Moses Jacob Ezekiel |

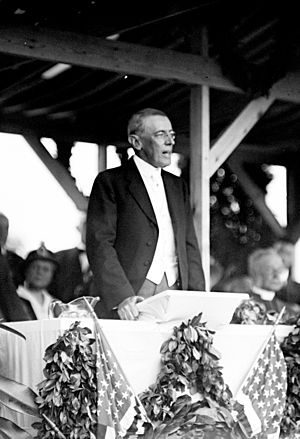

The Confederate Memorial is a special monument located in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia. It honors the soldiers, sailors, and marines from the Confederate States of America who died during the American Civil War. This memorial was officially approved in March 1906. A former Confederate soldier and sculptor named Moses Jacob Ezekiel was hired in November 1910 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to design it. President Woodrow Wilson revealed the memorial to the public on June 4, 1914. This date was also the 106th birthday of Jefferson Davis, who was the President of the Confederate States.

Since 1914, the area around the memorial has changed a little due to new burials. Some big changes were suggested over the years, but none of them happened. For many years, most U.S. Presidents have sent a special wreath to be placed at the memorial every Memorial Day. However, some presidents have chosen not to, and this tradition is a topic of debate.

Because Arlington National Cemetery is managed by the U.S. Department of the Army, a group called The Naming Commission looked at the monument in March 2022. They suggested that the memorial should be taken down. The Secretary of Defense will decide what happens to it.

Contents

Creating a Confederate Space at Arlington

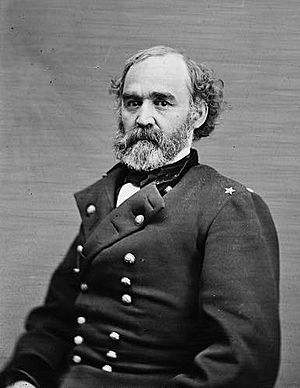

Arlington National Cemetery was started in June 1864. It was a burial ground for Union (United States of America) soldiers who died in the Civil War. The first soldier was buried there on May 13, 1864. However, official permission for burials was given by Major General Montgomery C. Meigs on June 15, 1864. Meigs was the Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, meaning he was in charge of supplies and logistics.

Some Confederate soldiers were also buried at Arlington at first. These included prisoners of war who died or were executed as spies. Some were also soldiers who died on battlefields. For example, in 1865, General Meigs decided to build a monument for Civil War dead. Workers collected the bodies of 2,111 Union and Confederate soldiers from around Washington, D.C. Many of these bodies could not be identified. Even though Meigs did not plan to collect Confederate remains, both Union and Confederate soldiers were buried together under the monument he built.

However, the U.S. government did not allow people to decorate Confederate graves at the cemetery. General Meigs, who managed the cemetery, refused to let families place flowers on their loved ones' graves. In 1868, when families wanted to decorate graves on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day), Meigs ordered them to be kept out. Union veteran groups also felt that Confederate graves should not be honored. In 1869, members of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Union soldiers' group, watched over Confederate graves to make sure they were not honored. Cemetery officials also refused to allow any monuments for Confederate dead or new Confederate burials.

President McKinley's Speech in 1898

The government's policy about Confederate graves at Arlington changed around the end of the 1800s.

The Spanish–American War in 1898 was the first time since the Civil War that Americans from both the North and South fought together against a foreign country. After the war ended, celebrations were held across the U.S. However, many Southerners were not fully supportive of the war or President William McKinley's plans for new territories.

President McKinley traveled across the South in December 1898 to encourage unity. He had seen neglected Confederate graves in Virginia in 1896, and it bothered him. In a speech in Atlanta on December 14, 1898, McKinley said that the government would now start taking care of Confederate graves. He called it "a tribute to American valor." This speech impressed many Southerners. They saw it as a sign of peace and national unity.

The Confederate Section at Arlington

President McKinley's speech encouraged Dr. Samuel E. Lewis to seek better care for Confederate graves. Lewis was a former surgeon for the Confederate States Army (CSA). He was also a leader of a veterans' group called the United Confederate Veterans (UCV). In 1898, Lewis counted all the Confederate graves at Arlington National Cemetery. He found 136 identifiable graves, much more than cemetery officials thought existed. These graves were spread out, and their headstones looked like those of civilian workers or former slaves. Lewis was especially upset that they looked similar to the headstones of black people.

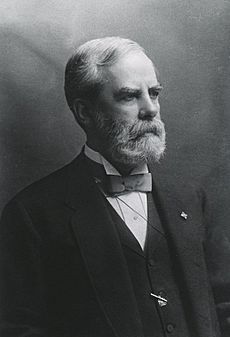

On June 5, 1899, Lewis and other Confederate veterans asked President McKinley to move the Confederate dead to a special "Confederate section." McKinley liked the idea. A former Confederate general, Marcus Joseph Wright, helped write a law to approve the reburials. Senator Joseph Roswell Hawley, a former Union general, introduced the bill in Congress. Congress approved the plan in 1900 and set aside money for it. The plan said the reburials should happen near where Spanish-American War soldiers had recently been buried. McKinley signed the bill into law on June 6, 1900. A list of the dead was published so families could move remains closer to home if they wished.

Disagreement About the Section

After June 1900, some women's groups, like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), did not want any Confederate dead to stay at Arlington. They believed Confederate soldiers should be buried in Southern soil. They also felt that Confederate families should not rely on the Union government for grave space. Some groups also wanted to rebury soldiers in the South so they could build pro-Confederate monuments there.

To overcome this disagreement, Dr. Lewis worked to get support for the "Confederate section." He got approval from many former high-ranking Confederate officers. He also found that other Confederate veteran groups approved of the plan. Lewis and his supporters argued that only the U.S. government had enough money to properly care for the many Confederate graves at Arlington.

Lewis also won over Congress and the government by showing that the women's groups did not represent most Southerners. He got his own veterans' group, the UCV, to pass resolutions supporting the Confederate section. He also gained the support of another important women's group in Washington, D.C. Lewis convinced these groups that their importance would continue if they organized Civil War events at Arlington. These efforts worked. In 1901, a group of Confederate veterans convinced Secretary of War Elihu Root to go ahead with the reburials at Arlington.

The Reburial Process

Reburials began in April 1901 and finished in October of that year. It's not clear exactly how many Confederate dead were moved. Some sources say 128 bodies, while others say 264, 267, or even more. These differences might be because a law in 1912 allowed any Confederate veteran living near Washington, D.C., to be buried in the Confederate section.

The Confederate dead were reburied on about 3.5 acres of land on the west side of Arlington National Cemetery. The graves were placed in a pattern of circles, not straight rows. This was done to show the South's effort to find its place in the newly united country. The area was landscaped by spring 1903.

The 1899 law required the government to provide standard headstones for the new Confederate graves. These headstones were 36 inches tall and had pointed tops. They were made of granite or marble, just like others in the cemetery. Each marker had a number, the person's name, their regiment, and "C.S.A." (Confederate States Army) written on it.

The first Confederate Memorial Day events in the Confederate section were held on June 7, 1903.

Building a Memorial

The Army Corps of Engineers marked a central grassy area in the Confederate section for a memorial. Confederate groups noticed this and started talking about building one.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) was one of the groups that wanted to build a memorial. Mrs. Mary Taliaferro Thompson asked the War Department for permission in 1902, 1903, and 1905, but was denied each time. Still, various UDC chapters started raising money for a memorial.

Mrs. Thompson tried again in 1906 and succeeded. She worked closely with Representative John Sharp Williams from Mississippi. On March 4, 1906, Secretary of War William Howard Taft gave the UDC permission to build a memorial in the center of the Confederate section. Taft's letter said the War Department had to approve the design and words on the monument. Mrs. Lizzie George Henderson, President-General of the UDC, accepted these terms on March 13, 1906.

Rep. Williams announced Taft's approval at the Confederate Memorial Day ceremony on June 4, 1906. He called for a monument and donated the first $50 for its construction.

Forming the ACMA

The Arlington Confederate Memorial Association (ACMA) was formed in 1906 to help build the memorial. It soon became clear that the UDC would need to take over the fundraising, design, and construction because the work was too much for the small ACMA board. On June 19, 1907, the UDC officially took over the project.

The UDC asked Cornelia Branch Stone to help reorganize the ACMA. She was a member of a UDC chapter in Texas. After some meetings, the ACMA agreed to become part of the UDC. Under the new rules, the President-General of the UDC became the President of the ACMA.

Cornelia Branch Stone was the first president of the reorganized ACMA, serving from 1907 to 1909.

Raising Money

The UDC contributed $500 to the memorial fund early on. In December 1906, reports said the ACMA had between $3,000 and $4,000 and aimed to raise $25,000. The UDC also agreed to donate $1,500 every year until the memorial was finished.

Fundraising went quickly while Stone was president. In July 1907, a wealthy stockbroker named Thomas Fortune Ryan donated $10,000. To help raise more money, the ACMA got support from important people. Former Confederate General Stephen D. Lee encouraged all UCV camps to donate. In February 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt also strongly supported the project. By November 1908, over $8,000 had been raised, and by 1910, nearly $20,000.

In 1910, the UDC sold special Christmas Seals to raise money. The goal was to raise the remaining $35,000 needed.

Designing the Memorial

Choosing the Artist

When Stone stepped down as president in 1909, she suggested forming a committee to choose the memorial's design. The committee first met on May 16, 1910. They initially thought about a design showing General Robert E. Lee in battle. However, this idea was later dropped.

At a meeting on October 31, 1910, the committee decided to choose a famous artist to propose a design. Hilary Herbert suggested Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a Confederate Army veteran and a well-known sculptor.

The UDC worried Ezekiel might refuse the job because he was known to be difficult and had lost other monument competitions. To convince him, the UDC committee agreed to give Ezekiel complete artistic control over the design.

Meetings with Moses Ezekiel

Ezekiel had already thought about a design for the Confederate Memorial. He lived in Italy but was in the U.S. in May 1910 for another statue dedication. While waiting to see President William Howard Taft, he got the idea for the Confederate Memorial.

Herbert and writer Thomas Nelson Page met with Ezekiel in Washington, D.C., on November 5, 1910. Ezekiel really wanted the job. They visited the Confederate section at Arlington and discussed the memorial's size and placement. Ezekiel sketched his idea for them. He also made it clear he would work in Italy and would not accept design changes from the ACMA.

The next day, the design committee held an emergency meeting. Ezekiel presented his idea: a large female figure representing the South, holding a wreath and resting her hand on a plow. This figure would stand on a circular base surrounded by other figures showing the South's sacrifices.

The committee was very impressed and offered him the job. On November 7, Ezekiel signed a contract to design and build the memorial. It was to be finished by November 1913 and cost $10,000. Some historians say Ezekiel took the job only because he had full control over the design.

Developing the Design

Just three days after Ezekiel signed the contract, the UDC convention met. They were so excited that they voted to increase the memorial's budget by $15,000, making the total $50,000. This was to make the memorial larger and more impressive. Of this, $10,000 was for shipping and setting up the memorial.

When Ezekiel heard about the extra money, he immediately made a new, bigger model. He increased the number of figures around the base from 15 to 32 and changed the base material from granite to bronze.

Ezekiel felt this was his most important project. He stopped all other work to focus on it. He also tried to keep visitors away from his studio in Rome to avoid public discussion of his design. However, some changes were made based on comments from visitors. For example, he changed words on a shield from "free trade" and "state's rights" to "Constitution."

As his design neared completion in late 1911, Ezekiel started sending photos of his work to the ACMA committee. He asked them to keep the photos private. A two-thirds size model was finished in early 1912.

Fundraising for the Enlarged Design

More money was raised after 1910 to cover the increased cost. Even some Union soldiers donated, like the 23rd New Jersey Regiment, which gave $100. Ezekiel agreed to donate his work as sculptor, so all the money could go towards buying bronze and casting the memorial. By February 1912, $24,000 still needed to be raised.

As the casting finished in November 1913, the ACMA announced they had raised over $50,000. By November 1914, a total of $56,262 had been raised for the memorial.

Building the Memorial

Laying the Cornerstone

Work on the memorial was on schedule. In June 1912, the ACMA planned a dedication for a year later.

The ACMA set Tuesday, November 12, 1912, at 2:00 pm, to lay the cornerstone. This date was the first day of the UDC's yearly convention in Washington, D.C. President William Howard Taft agreed to speak.

Over 10,000 people were expected to attend. Taft had just lost the 1912 presidential election to Woodrow Wilson, but he still kept his promise to speak. It was his first speech since losing the election.

About 6,000 people attended the cornerstone laying on November 12. The 15th Cavalry Regiment Band played music. Speakers included former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan and Hilary A. Herbert. Herbert also asked Corporal James R. Tanner, a former leader of the Grand Army of the Republic (a Union veterans' group), to speak briefly. Tanner had lost both legs in the war and was known for his work after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Some in the audience murmured when Tanner spoke.

After the speeches, the cornerstone was laid. It contained a time capsule with many items, including a copy of the 1900 law, Taft's letter, UDC membership lists, Confederate state flags, and old money. Hilary Herbert, James Tanner, and Miss Mary Custis Lee (General Robert E. Lee's daughter) ceremonially placed mortar under the cornerstone. The cornerstone was then lowered. Mrs. Cordelia Powell Odenheimer of the UDC placed mortar on top. The ceremony ended with a blessing.

Afterward, UDC members planted a redwood tree near the monument and named it "Robert E. Lee."

Dedication Delays

Work on the monument faced delays. Funding was not the problem. The first delay happened in early 1913 because Ezekiel couldn't get copies of the Confederate state shields in time. This forced the ACMA and UDC to postpone the dedication from June 1913 to November 5.

More delays followed. In August 1913, an accident during the casting process delayed the memorial's delivery by three months. The Confederate Memorial was finally finished in November 1913. It was shipped to the U.S. in early 1914 and arrived at the Washington Navy Yard on January 10, 1914.

The memorial came in many pieces that needed assembly. A civil engineer named A. C. Weeks helped prepare the site and oversaw the monument's setup. The ACMA planned to uncrate and set up the memorial in early March 1914 and set a new dedication date for April 27.

But construction problems caused another delay. The company providing granite for the base couldn't deliver it in time. The ACMA canceled that contract and hired a Maryland firm instead. The Maryland company said the base would be ready by May 22, so the ACMA rescheduled the dedication for Confederate Memorial Day, June 4.

The UDC wanted the dedication to be a very special event. Florence Butler, who led the dedication program committee, made sure there were only a few short speeches. President Woodrow Wilson, who was from Virginia, was invited to be the main speaker, and he accepted. His participation almost caused a problem when he initially decided not to attend the Grand Army of the Republic's Memorial Day ceremonies. The GAR was very upset, but Wilson quickly agreed to attend their event, and the issue was resolved.

Dedicating the Memorial

The dedication ceremony for the Confederate Memorial took place on June 4, 1914. Many important people and Confederate groups were invited. Only one Union veterans' group, the 23rd New Jersey Regiment, was invited because of limited seating. However, no one from that unit attended.

The ceremony started with music from the 5th Cavalry Regiment Band for the over 4,000 people present, including all members of Congress. The Rev. Dr. Randolph H. McKim gave the opening prayer. Hilary Herbert was the master of ceremonies. Speakers included former Confederate general Bennett H. Young and Washington Gardner, a former Union sergeant. Colonel Robert Edward Lee III, General Robert E. Lee's grandson, also spoke. Herbert then officially gave the memorial to the UDC, and Mrs. Daisy McLaurin Stevens, President of the UDC, accepted it.

After the speeches, 11-year-old Paul Herbert Micou, Hilary Herbert's grandson, unveiled the Confederate Memorial. A 21-gun artillery salute followed. Then, Mrs. Stevens presented the memorial to President Wilson as a gift to the American people.

The ceremony was supposed to end with a speech by President Wilson, singing, wreath-laying, and a final blessing. But a thunderstorm began as the President was finishing his speech. Most people rushed to their cars and left. The President also left, and the ceremony ended suddenly. The floral tributes were quickly placed at the memorial's base.

About the Memorial

The Confederate Memorial is in a circular grassy area called Stonewall Jackson Circle in Section 16 of Arlington National Cemetery. Sculpted in the Baroque style by Moses Ezekiel in his studio in Rome, Italy, the bronze and casting cost about $41,770. Ezekiel did not charge for his work as a sculptor. The memorial was cast in Berlin, Germany. Shipping and setting it up cost about $8,229.

The memorial has a bronze statue on top of a bronze base, which sits on a granite foundation. The granite base is about 3 feet high. The bronze base above it is called a plinth. Before the foundations were laid, the entire Confederate section was leveled. Roads were removed and replaced with grass. The road around the site became a cement walk.

The memorial is usually called the "Confederate Memorial." Moses Ezekiel preferred the name "New South." It is very detailed and shows Ezekiel's training in Germany and the artistic style of the Victorian era.

At 32 feet tall, the Confederate Memorial is one of the tallest monuments at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Figure of "The South"

The very top of the memorial has a large statue of a woman representing the South. She faces south to honor the Confederacy and to always have the sun shine on her face, symbolizing favor. Her head wears an olive wreath, a symbol of peace. Her left hand holds a laurel wreath towards the south, honoring the sacrifices of Southern soldiers. Her right hand holds a pruning hook that rests on a plow. This represents peace, reconciliation, and hope for future prosperity through hard work.

The figure stands on a round pedestal decorated with palm branches and four urns. Numbers on the urns refer to the four years of the American Civil War (1861, 1862, 1863, and "1864-65"). Below this is a round base with the words: "And they shall beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks." This is a quote from the Bible (Isaiah 2:4).

Below this base is a frieze (a decorative band) with 14 shields. Each shield shows the symbol of one of the 11 Confederate states, plus the border states of Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland.

32 Figures on the Mount

Below the shields is a round section with 32 life-size figures. At the front, facing south, is the armored figure of Minerva, the Roman goddess of war and wisdom. Minerva tries to support a fallen woman, who also represents the South. This woman leans against a shield with the words "The Constitution." Behind Minerva's head, "Spirits of War" blow trumpets, calling Southerners to help their country.

On either side of the fallen woman are figures representing different parts of the Confederate armed forces: a miner, sailor, sapper (engineer), and soldier. There are also figures of a uniformed black slave following his master to war. The UDC stated in 1914 that this figure is "a faithful Negro body-servant following his young master." This image was inspired by a story from 1887 called Marse Chan: A Tale of Old Virginia.

On the other sides of the monument are more figures. These show the sacrifices and bravery of all kinds of people in the Confederacy. They include:

- A military officer kissing his baby, held by a weeping black "mammy" (a term for a black nanny) with another child clinging to her.

- A blacksmith leaving his tools as his sad wife watches.

- A clergyman and his grieving wife saying goodbye to their teenage son who has joined the army.

- A young lady putting a sword and sash on her boyfriend.

The sculptor Moses Ezekiel included the "faithful black servants" on purpose. He wanted to challenge what he called "lies" about the South and slavery, especially from books like Uncle Tom's Cabin. He aimed to show black slaves supporting the Confederate cause.

An oak tree spreads its branches behind some of the figures. It represents the support families gave to the Confederate cause and the strength of Confederate families.

Base Inscriptions

The 32 figures stand on an eight-sided base. The front (south side) of this base shows the Great Seal of the Confederacy. Below the seal are these words:

TO OUR DEAD HEROES

BY

THE UNITED DAUGHTERS

OF THE CONFEDERACY

VICTRIX CAUSA DIIS

PLACUIT SED VICTA CATONI

This Latin phrase means: "The Victorious Cause was Pleasing to the Gods, But the Lost Cause Pleased Cato." It comes from an ancient Roman poem. It refers to a Roman senator named Pompey who lost a fight against Julius Caesar but was still admired for his moral actions.

On the north side of the memorial, these words are written:

NOT FOR FAME OR REWARD

NOT FOR PLACE OR FOR RANK

RANDOLPH HARRISON MCKIM

NOT LURED BY AMBITION

OR GOADED BY NECESSITY

BUT IN SIMPLE

OBEDIENCE TO DUTY

AS THEY UNDERSTOOD IT

THESE MEN SUFFERED ALL

SACRIFICED ALL

DARED ALL — AND DIED

The northwest side of the base says:

M. Ezekiel * Sculptor

Rome MCMXII

The northeast side of the base says:

MADE BY

AKTIEN-GESELLSCHAFT GLADENBECK

BERLIN-FRIEDRICHSHAGEN-GERMANY

BRONZE FOUNDERY

The east and west sides of the base have pedestals with urn-like lamps topped with bronze "eternal flames."

What People Think of It

When the memorial was first revealed, The Washington Post praised it. They liked its focus on peace, its message about the South fighting for constitutional rights (not slavery), and its images of the common soldier's sacrifices. European art critics called it "a marvel of facial expression." Colonel William Couper of the Virginia Military Institute called it "magnificent and impressive" in 1933.

More recently, critics have different opinions. Keith Gibson, director of the VMI museum system, says it's a "superb example of Ezekiel's style." However, he notes its "hard contours." Historian Katherine Allamong Jacob says it's "intensely dramatic" but also "a little sentimental." In 2007, a reporter called it "ornate and romantic." Kirk Savage, an art history professor, says the memorial is "clearly the product of white supremacist thinking." Historian Erika Lee Doss agrees, calling it "a pro-southern textbook illustrated in bronze."

History of the Memorial

In August 1915, the Secretary of War decided that the U.S. government would take care of the Confederate Monument.

As of November 2013, the Confederate Memorial is one of only three places at Arlington National Cemetery where public memorial services can be held. The others are the Memorial Amphitheater and the John F. Kennedy Grave.

Burials at the Memorial

Burials continued in the Confederate section after the memorial was finished. The first was Thomas Findley on June 11, 1914, just days after the dedication. His burial caused controversy because the War Department gave him full military honors, which upset Union veterans.

Four important people are buried at the compass points around the Confederate Memorial. These graves are different from the circular pattern of other burials. They belong to Moses Ezekiel, Lieutenant Harry C. Marmaduke, Captain John M. Hickey, and Brigadier General Marcus J. Wright.

Moses Ezekiel died in Italy in 1917. His body was brought back to the U.S. after World War I. His funeral was held in the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater on March 30, 1921. He was the first person to have a funeral in that new building. He was buried on the east side of the memorial.

Brigadier General Wright was buried on the south side of the memorial on December 29, 1922. Captain Henry H. Marmaduke, the last known surviving officer of the ironclad warship CSS Virginia, was buried on the west side on November 17, 1924. Captain John M. Hickey was buried on the north side on October 3, 1927.

It is not clear why these four were buried next to the memorial and not elsewhere. Ezekiel, Wright, and Hickey were very important in creating the Confederate section and the memorial. Marmaduke's notable war service may have been the reason for his special burial spot.

Other History of the Memorial

The Confederate Memorial is the main focus of Confederate Memorial Day events in the Washington, D.C., area. President Woodrow Wilson attended the first four events from 1915 to 1918. He started the tradition of presidents sending wreaths to the event. Later presidents, like Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, also attended or sent wreaths.

The number of people attending these events has changed a lot over the years. For example, over 2,000 people attended in 1912, but only about 150 attended in 2007.

In 1931, new memorials were suggested for the Confederate section. This idea came from a debate about burying LaSalle Corbell Pickett, the wife of Confederate Major General George Pickett. She wanted to be buried next to her husband in Hollywood Cemetery in Virginia, but officials refused. Her grandson wanted her buried at Arlington and her husband's remains moved there too. This led to a plan to build statues of Generals Pickett, Longstreet, and Robert E. Lee at Arlington. However, Hollywood Cemetery officials then agreed to bury Mrs. Pickett next to her husband, and the plans for new statues at Arlington were not carried out.

There were also attempts in the 1930s to add more Confederate memorials at Arlington. One idea was to put a statue of Robert E. Lee somewhere in the cemetery. Another was to add the names of Confederate figures like Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson to columns in the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater. However, none of these proposals were approved by Congress.

Confederate Memorial Day ceremonies moved to the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater in 1936. While wreath-layings still happened at the memorial, most of the event was in the amphitheater. The ceremonies moved back and forth between the memorial and the amphitheater over the years. More recently, in the 1990s and 2000s, the ceremonies have been held at the Confederate Memorial.

In 2010, the Confederate Memorial appeared in a novel for the first time. In Alice Randall's book Rebel Yell, two African American characters discuss the memorial's images of black slaves and what it means for African Americans today.

On June 8, 2014, the United Daughters of the Confederacy hosted a ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary of the Confederate Memorial's dedication.

Ezekiel's Descendants' View

In 2017, after violence at a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, led to more calls for the removal of Confederate monuments and memorials, twenty of Moses Ezekiel's descendants wrote a letter. They published it in The Washington Post, asking for the monument to be removed.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |