Confucianism facts for kids

Confucianism is a way of thinking and living that started in ancient China. It's often seen as a tradition, a philosophy, or even a religion. This way of life grew from the ideas of a wise Chinese thinker named Confucius, who lived from 551 to 479 BCE.

Confucianism teaches that families and society should live in harmony. Followers believe that people are naturally good. They also think that everyone can learn, improve, and become their best self. This happens through personal effort and working together, especially by improving oneself.

Confucianism has five main rules for good behavior, called the Five Constants:

- Ren (being kind and humane)

- Yi (doing what is right and fair)

- Li (having good manners and following traditions)

- Zhi (智; zhì: being wise and having knowledge)

- Xin (being honest and trustworthy)

There are also four classic virtues, and Yi (doing what is right) is one of them:

- Yi (doing what is right)

- Loyalty (忠; zhōng)

- Filial piety (孝; xiào)

- Continence (节; 節; jié, meaning self-control)

Many other good values are part of Confucianism. These include 诚; chéng; 'honesty', 勇; yǒng; 'bravery', 廉; lián; 'being fair and not corrupt', 恕; shù; 'kindness and forgiveness', a 耻; chǐ; 'sense of right and wrong', 温; wēn; 'gentleness', 良; liáng; 'being kindhearted', 恭; gōng; 'respect', 俭; jiǎn; 'being careful with money', and 让; ràng; 'modesty'.

Confucianism has greatly influenced cultures and countries in East Asia. This includes China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

Contents

Understanding Confucian Ideas

In Chinese, there isn't one single word that means exactly "Confucianism." The closest word is ru (儒; rú). In modern Chinese, ru means 'scholar' or 'a learned person.' In older Chinese, it also meant 'to teach' or 'to make better.'

Relationships and Harmony

Confucianism teaches that society works best when everyone knows their role and does their part well. Each person has different duties depending on their relationships with others. For example, you are a younger person to your parents and elders. You are an older person to your younger siblings or students.

Younger people should show respect to their elders. But elders also have duties to be kind and caring toward younger people. This idea of giving and receiving applies to all relationships, like between a husband and wife. This idea of mutual respect is still important in East Asian cultures today.

Confucianism describes five main relationships:

- Ruler and those ruled

- Father and son

- Husband and wife

- Older brother and younger brother

- Friend and friend

Each person in these relationships has specific duties. These duties even extend to family members who have passed away. The only relationship where respect for elders isn't the main focus is between friends. Here, equal respect is most important. These duties are often shown through special ceremonies, like wedding or funeral rituals.

Filial Piety: Respecting Family

In Confucian thinking, 孝; xiào is a very important virtue. It means showing deep respect for your parents and ancestors. It also means respecting the different levels of authority in society, like father over son, older over younger, and male over female.

More simply, filial piety means being good to your parents and taking care of them. It also means behaving well outside the home so that you bring honor to your family. You should do your job well to earn money to support your parents and honor your ancestors. It means not being rebellious, showing love, respect, and support. For a wife, it means respecting her husband and taking care of the family. It also includes showing courtesy, ensuring there are male heirs, and being good to your siblings. You should wisely advise your parents, show sadness if they are sick or pass away, and perform ceremonies after their death.

Filial piety is a key value in Chinese culture. Many famous stories, like "The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars," show how children practiced filial piety in the past. Even though China has many different religious beliefs, respect for family is common to almost all of them.

Loyalty and Good Leaders

Confucius taught that a leader should be obeyed because they are morally good, not just because they have power. Loyalty doesn't mean blindly following orders. Leaders also have duties to their people. Confucius said, "a prince should treat his ministers with proper respect; ministers should serve their prince with faithfulness (loyalty)."

If a ruler is bad, the people have the right to remove them. A good Confucian person is also expected to speak up and advise their leaders when needed. At the same time, a good Confucian ruler should listen to their ministers' advice, as this helps them govern better.

Good Government

子曰:為政以德,譬如北辰,居其所而眾星共之。

The Master said, "A ruler who governs by being good is like the North Star. It stays in its place, and all the other stars turn towards it."

A main Confucian idea is that to lead others, you must first lead yourself. A good ruler's personal goodness (called de) spreads good influence throughout the whole country. By being a calm and steady leader, the ruler helps everything in the kingdom work smoothly without needing to control every small detail.

This idea comes from ancient beliefs that the king was a link between the sky, people, and Earth. The emperors of China were seen as chosen by Heaven. They had the Mandate of Heaven, which was a very important idea in how China was ruled for centuries.

Meritocracy: Earning Your Place

Confucius introduced many new ideas, including meritocracy. This means that people should get positions based on their abilities and skills, not just their family background. This idea led to the imperial examination system in China. This system allowed anyone who passed a difficult test to become a government official. This job brought wealth and honor to their whole family.

The Chinese imperial examination system began during the Sui dynasty. Over hundreds of years, this system grew. Eventually, almost anyone who wanted to become an official had to prove their worth by passing these written government exams. The idea of meritocracy still exists in China and East Asia today.

Confucianism and Martial Arts

After Confucianism became the official way of thinking in China, it influenced almost every part of Chinese society, including martial arts. Even though Confucius himself didn't focus on martial arts (except for archery), his ideas later shaped many educated martial artists. For example, Sun Lutang in the 19th century was greatly influenced by Confucianism, as well as Buddhism and Daoism.

See also

Images for kids

-

Confucius in a painting from a Western Han tomb in Dongping, Shandong.

-

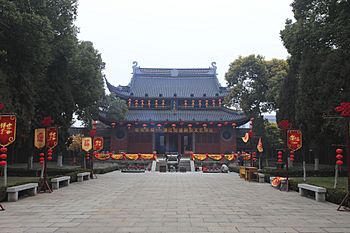

Worship at the Great Temple of Lord Zhang Hui, a family temple of the Zhang family in Qinghe, Hebei.

-

A family temple of the Zeng family and a cultural center in Cangnan, Zhejiang.

-

A Korean Confucian ceremony in Jeju.

-

The Chinese dragon is an ancient symbol in Chinese culture. It represents the highest god and power.

More to Explore

In Spanish: Confucianismo para niños

In Spanish: Confucianismo para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |