Coppermine expedition facts for kids

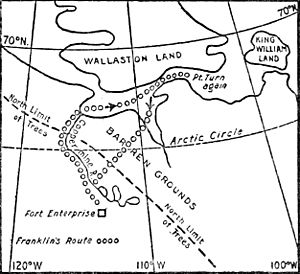

The Coppermine expedition of 1819–1822 was a British journey to explore and map the northern coast of Canada. It aimed to find the Northwest Passage, a sea route through the Arctic. This was the first of three Arctic trips led by John Franklin. Other important explorers like George Back and John Richardson were also part of this team.

The expedition faced many problems. Planning was poor, and they had bad luck. Help from local fur trading companies and native peoples was not as much as expected. Their supplies often ran out. Also, the weather was very harsh, and there was little game to hunt. This meant the explorers were often close to starving.

They did reach the Arctic coast. But they could only explore about 500 miles (800 km) before supplies ran out. Winter also began, forcing them to turn back. What followed was a very tough journey back through unknown lands. They were starving, sometimes eating only lichen. Sadly, 11 of the 22 people on the trip died. The survivors were saved by members of the Yellowknives Nation. These people had thought the explorers were already dead.

After the expedition, fur traders criticized Franklin. They said his planning was messy, and he didn't adapt well. But back in Britain, he was seen as a hero. People admired his courage in such extreme hardship. The public loved his story. He became known as "the man who ate his boots" because of a desperate thing he did to survive.

Contents

Why Explore the Arctic?

After the big wars with Napoleon, the British Navy looked to the Arctic. Sir John Barrow was a key person behind this. They wanted to find the Northwest Passage. This was a hoped-for sea route around the north of Canada. It would let European ships easily reach markets in Asia.

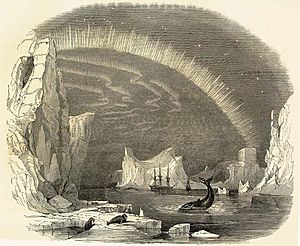

Whalers had found whales in the Bering Strait with tusks from Greenland. This suggested a passage might exist. But the many islands north of Canada were mostly unmapped. No one knew if a clear, ice-free route was possible.

By 1819, Europeans had only seen Canada's northern coast twice. In 1771, Samuel Hearne followed the Coppermine River to the sea. This was about 1,500 miles (2,400 km) east of the Bering Strait. In 1789, Alexander Mackenzie followed the Mackenzie River to the open sea. This was about 500 miles (800 km) west of the Coppermine River's mouth.

In 1818, Barrow sent his first expedition. It was led by John Ross. But Ross turned back after entering Lancaster Sound. He thought it was a bay, but it was actually the true entrance to the Northwest Passage. At the same time, David Buchan tried to sail directly to the North Pole. He found that thick ice north of Spitsbergen blocked the way.

The next year, Barrow planned two more Arctic trips. One by sea, led by William Edward Parry, would continue Ross's work. It would look for the Northwest Passage from Lancaster Sound. At the same time, a group would travel overland to the Canadian coast. They would go by the Coppermine River. Their job was to map as much coastline as possible. They might even meet Parry's ships. John Franklin was chosen to lead this overland group. He had commanded one of Buchan's ships the year before.

Getting Ready for the Journey

Franklin's instructions were not very clear. He was to travel overland to Great Slave Lake. From there, he would go to the coast using the Coppermine River. Once at the coast, he was told to head east towards Repulse Bay. He hoped to meet William Edward Parry's ships there. But he also had the choice to go west. He could map the coast between the Coppermine and Mackenzie Rivers. Or he could even go north into completely unknown seas.

A bigger problem was the very small budget for the expedition. John Franklin was to take only a few naval people. He would rely on outside help for most of the trip. Métis voyageurs were supposed to help with manual labor. These were supplied by the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company. Local Yellowknives First Nation members would be guides. They would also provide food if Franklin's supplies ran out.

Only four naval people went with John Franklin. They were the doctor and naturalist John Richardson, who was also second-in-command. There were two young officers, Robert Hood and George Back. Back had sailed with David Buchan in 1818. The last was an ordinary sailor named John Hepburn. Another sailor, Samuel Wilkes, was supposed to go. But he got sick in Canada and returned to England.

The Expedition Begins

First Stops and Challenges

The Coppermine Expedition left Gravesend, England, on May 23, 1819. They sailed on a Hudson's Bay Company ship. The trip started with a funny moment. The ship stopped briefly off the Norfolk coast. George Back had some business there. But a good wind came up before he returned. The ship sailed off, leaving Back to catch up by coach and ferry to Orkney.

A more serious problem came up in Stromness. The expedition, now with Back, tried to hire local boatmen. These men were needed to pull boats for the first part of the journey across Canada. But herring fishing was very good that year. So, the local men were not keen to join. Only four men were hired. Even they agreed to go only as far as Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca.

On August 30, 1819, Franklin's men reached York Factory. This was the main port on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay. Here, they began the 1,700-mile (2,700 km) trek to the Great Slave Lake. They immediately faced their first supply problems. Much of the help promised by the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company did not appear. The two companies had been fighting each other. So, they had few resources to share.

Franklin got a boat that was too small for all his supplies. He was told the rest would be sent later. He traveled along normal trading routes to Cumberland House. This was a small log cabin with 30 Hudson's Bay men. Franklin and his men spent the harsh winter there.

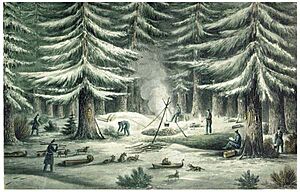

Journey to Fort Chipewyan

The next January, Franklin, Back, and Hepburn went ahead. They traveled through pine forests to Fort Chipewyan. Their goal was to hire voyageurs and arrange supplies. Canadian guides led the Britons, who had no experience with harsh Canadian winters. The journey was very hard. The extreme cold froze their tea almost instantly. It also froze the mercury in their thermometers.

They had no tents. So, they were happy for snowfall, which added insulation over their blankets. Franklin later wrote that the journey had "a great mix of good and bad times. If I balanced them, I suspect the bad would be much more."

The advance group reached Fort Chipewyan in late March. They had covered 857 miles (1,380 km) in six weeks. Once there, Franklin found it much harder to equip his expedition than he expected. The harsh winter meant food was scarce. He got only a vague promise that hunters would feed them along the way. He was also told the chief of the Coppermine First Nations would help.

The best voyageurs were busy with the fight between the two fur trading companies. Or they didn't want to risk a journey into unknown lands with uncertain supplies. Finally, Franklin hired 16 voyageurs. But most of them were not as skilled as he wanted.

Setting Up Fort Enterprise

Franklin reunited with Hood and Richardson. The group left for the Great Slave Lake in July. Ten days later, they reached the trading post at Fort Providence. Here, they met Akaitcho. He was the leader of the local Yellowknives First Nation. The North West Company had hired him to guide and hunt for Franklin's men. Akaitcho was described as a very smart and clever man. He understood the idea of the Northwest Passage. He listened patiently as Franklin explained how it would bring wealth to his people.

Akaitcho seemed to realize Franklin was overstating the benefits. He asked a question Franklin could not answer: If the Northwest Passage was so important for trade, why hadn't it been found already?

After making his point, Akaitcho discussed his terms with Franklin. His tribe's debts to the North West Company would be canceled. They would also get weapons, ammunition, and tobacco. In return, his men would hunt and guide for Franklin on the trip north down the Coppermine River. They would also leave food supplies for their return. However, they would not enter Inuit lands far north on the river. The Yellowknives and Inuit did not trust each other. Akaitcho warned Franklin that in such a hard year, he could not promise food would always be available.

Franklin and his men spent the rest of the summer of 1820 traveling north. They went to a spot on the Snare River. Akaitcho had chosen this as their winter home. Food quickly became scarce. The voyageurs began to lose trust in their leader. Franklin's threats of harsh punishment stopped a mutiny for a short time. But it also reduced the remaining good feelings the men had. The camp, which Franklin named Fort Enterprise, was reached without more trouble. They built wooden huts for winter.

Down the Coppermine River

The expedition's second winter in Canada was also hard. Supplies arrived only sometimes. The rival companies preferred to let the other provide them. Ammunition ran low. The First Nations hunters were not as effective as hoped. Finally, with the group facing starvation, Back was sent back to Fort Providence. He had to pressure the companies to act. Back traveled 1,200 miles (1,900 km) on snowshoes. Often, he had no shelter but blankets and a deerskin. Temperatures were as low as -67°F (-55°C). Back returned with enough supplies for their immediate needs.

There was also ongoing trouble in the camp. The voyageurs, led by two interpreters, Pierre St Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, rebelled. Franklin's threats did not work. St Germain and Adam said going further into the wilderness meant certain death. So, the threat of execution for mutiny was silly. Willard Wentzel, the North West Company's representative, negotiated. This brought an uneasy peace. The arguments were not just among the voyageurs. Back and Hood had fallen out. They both liked a Yellowknives girl nicknamed Greenstockings. They would have fought a duel with pistols over her. But John Hepburn removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation calmed when Back was sent south. Hood later had a child with Greenstockings.

The winter of 1820–21 passed. Franklin set out again on June 4, 1821. His plans for the summer were unclear. He decided to explore east from the Coppermine's mouth. He hoped to meet William Edward Parry or reach Repulse Bay. There, he might get enough supplies from local Inuit. This would let him return directly to York Factory by Hudson Bay. But if Parry didn't appear, or he couldn't reach Repulse Bay, he would either go back the way he came. Or, if it seemed better, he would return directly to Fort Enterprise. This would be across the unknown Barren Lands east of the Coppermine River.

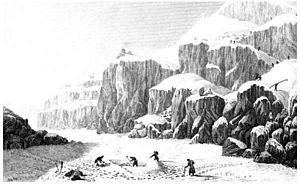

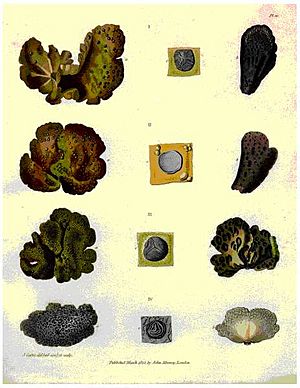

The journey down the Coppermine River took much longer than planned. Franklin quickly lost faith in his First Nations guides. They knew the area little better than he did. They kept saying the sea was close, then far, then close again. The ice on the rivers and lakes was still thick. For the first 117 miles (188 km), the canoes had to be pulled on sledges. The Arctic Ocean was finally seen on July 14. This was shortly before the expedition met its first Inuit camp. The Inuit fled. Franklin's men never got to contact them or trade for supplies as he hoped. The abandoned camp showed how little food was in the area. The dried salmon was rotting and full of maggots. The drying meat was mostly small birds and mice.

The First Nations guides turned for home as agreed. Wentzel also left. This left Franklin with fifteen voyageurs and his four Britons. Franklin told those leaving to leave food caches along the route. Most importantly, Fort Enterprise was to be stocked with a lot of dried meat. This last point was crucial because of the late season. Franklin now feared that if he didn't reach Repulse Bay, the sea would freeze. This would stop him from returning to the Coppermine River's mouth. If so, he would have to return directly across the Barren Lands. There, he and his men would depend on whatever food they could find. So, there was a real risk they would be starving by the time they reached Fort Enterprise. Franklin often repeated that well-stocked huts were vital for their survival.

At the Coppermine's mouth, Franklin headed east in three canoes. They had enough food for fourteen days. Storms often damaged the canoes, slowing their progress. Attempts to hunt for more food were unsuccessful. Franklin suspected the voyageurs were deliberately failing to find game. He thought they wanted to force him to turn back.

On August 22, after mapping about 675 miles (1,086 km) of coastline, Franklin stopped. He named this spot Point Turnagain, on the Kent Peninsula. It was about 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Cape Flinders. As he feared, rough seas and damaged canoes made returning via the Coppermine impossible. The group decided to return via the Hood River. From there, they would try to go overland across the Barren Lands.

The Hard Return Journey and Starvation

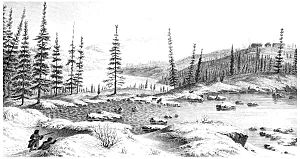

Their journey across the Barren Lands was extremely difficult. The ground was a dangerous area of sharp rocks. These cut their boots and feet. They also posed a constant threat of more serious injury. Richardson noted, "if anyone had broken a limb here his fate would have been melancholy indeed, as we could neither have remained with him, nor carried him on with us." The canoes were hard to carry. The voyageurs dropped them—Franklin suspected on purpose—and they became completely unusable.

Winter arrived early. Game became even scarcer than it already was. By September 7, 1821, the expedition's food was gone. Besides the rare deer they managed to kill, they ate barely nutritious lichens. They called these tripe de roche. They also ate the occasional rotting animal carcass left by wolves. They were so desperate that they even boiled and ate the leather from their spare boots.

On September 13, the group reached Contwoyto Lake. The next day, they arrived at the Contwoyto River. Their attempts to cross it were disastrous. The canoes overturned several times. One voyageur was stuck in waist-deep rapids for several minutes. It took four tries to rescue him. During this, Franklin also lost his journals and all the expedition's weather notes.

The voyageurs carried an average of 90 pounds (41 kg) each. They had been promised 8 pounds (3.6 kg) of meat a day when they signed up. They suffered most from the hunger. Their unhappiness again turned into rebellion. They secretly threw away some heavy equipment, including the fishing nets. This would be a serious loss. Richardson wrote that they "became desperate and were perfectly careless of the officers' commands."

The only thing that stopped them from leaving altogether was not knowing how to find Fort Enterprise by themselves. But they started to realize Franklin also had little idea where it was. His compass was not very useful. The magnetic direction for the area was unknown. And constant cloud cover made finding their way by the sun or stars impossible. A full mutiny was avoided only when they reached a large river on September 26. This was surely the Coppermine.

The group's joy at reaching the river quickly turned to sadness. It became clear they couldn't cross the river to reach Fort Enterprise without boats. Franklin guessed it was 40 miles (64 km) away on the other bank. The fast-flowing river was 120 yards (110 m) wide in places. Attempts to find a shallow spot to cross failed. The voyageurs, according to Richardson, "bitterly cursed their foolishness in breaking the canoe." They became "careless and disobedient... [and] stopped fearing punishment or hoping for reward." One of them, Juninus, slipped away. He perhaps hoped to reach safety alone, and never returned. Richardson himself risked his life trying to swim across the river with a rope tied around his waist. But he lost feeling in his limbs, sank, and had to be pulled back. Hypothermia drained his strength, leaving him very weak.

The starving group was weakening fast. The situation was saved by Pierre St Germain. He alone had the strength and will to build a makeshift one-person canoe. He used willow branches and canvas. The other men cheered when, on October 4, he crossed the river, pulling a rope. The rest of the group crossed one by one. The boat sank lower and lower in the water as they crossed. But all made it safely.

Fort Enterprise was now less than a week's walk away. But for some of the starving men, that would be too far. At the back of the line, the two weakest voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, collapsed. They were left where they fell. Richardson and Hood were also too weak to continue.

At this point, Franklin split his group. Back, the strongest remaining officer, was sent ahead. He went with three voyageurs to bring food back from Fort Enterprise. Franklin would follow more slowly with the remaining voyageurs. Hood and Richardson would stay in their camp. Hepburn would look after them. They hoped one of the other groups could bring them food. Franklin was worried about leaving Hood and Richardson. But they insisted the group would have a better chance of survival without them.

Franklin had gone only a short distance towards Fort Enterprise. Then four voyageurs—Michel Terohaute, Jean Baptiste Belanger, Perrault, and Fontano—said they couldn't continue. They asked to return to Hood and Richardson's camp. Franklin agreed. He struggled on towards Fort Enterprise with his five remaining companions. He grew weaker and weaker. No game could be found, even if any of them had been strong enough to hold a rifle. Recounting the story, Franklin made a comment that became famous: "There was no tripe de roche, so we drank tea and ate some of our shoes for supper."

Franklin's group reached Fort Enterprise on October 12, two days after Back. They found it empty and unstocked. The promised supplies of dried meat had not appeared. There was nothing to eat except bones from the previous winter. There were also a few rotting skins that had been used as bedding, and a little tripe de roche. A note from Back explained he had found the fort in this state. He was heading towards Fort Providence to look for Akaitcho and his First Nations members. The group despaired.

Two voyageurs, Augustus and Benoit, went upriver. They hoped to meet some First Nations people. The rest of the group stayed, too weak to go further. Two of the voyageurs lay down crying and waited to die. Even the usually hopeful Franklin wrote how quickly his strength was disappearing. None of them had eaten meat for four weeks.

The Rescue

Richardson and Hepburn struggled to Fort Enterprise. They were shocked by what they saw when they arrived on October 29, 1821. Of the four men left, only Peltier was strong enough to stand and greet them. The floorboards had been dug up for firewood. The skins covering the windows had been removed and eaten by the starving men. Richardson wrote that "the ghastly faces, wide eyes and ghostly voices of Captain John Franklin and those with him were more than we could at first bear."

For over a week, the men at Fort Enterprise survived on tripe de roche and rotten deerskins. They ate the skins complete with maggots, which tasted "as fine as gooseberries." Two of the voyageurs, Peltier and Samandré, died on the night of November 1. The third, Adam, was close to death. Hepburn's limbs began to swell from lack of protein. Finally, on November 7, help arrived. Three of Akaitcho's men came. Back, who had also lost a man to starvation, had finally found them. They brought food, caught fish for the survivors, and treated them "with the same tenderness they would have given their own infants." After gaining strength for a week, they left Fort Enterprise on November 15. They arrived at Fort Providence on December 11.

Akaitcho explained why Fort Enterprise had not been stocked with food. Part of the reason was that three of his hunters had died falling through ice on a frozen lake. Also, he had not received ammunition at Fort Providence. But he admitted the main reason the fort was empty. He believed the white men's expedition was very foolish. He thought they would not return to Fort Enterprise alive. Despite this, Franklin refused to blame Akaitcho. Akaitcho had shown him much kindness during the rescue. Also, because of the ongoing fight between the fur companies, Akaitcho had not received the payment he was promised.

What Happened Next

By almost any measure, the expedition was a disaster. Franklin had traveled 5,500 miles (8,900 km). He lost 11 of his 19 men. And he only mapped a small part of the coastline. He got nowhere near his goal of Repulse Bay or meeting William Edward Parry's ships. When the group arrived back at York Factory in July 1822, George Simpson of the Hudson's Bay Company wrote about it. He had been against John Franklin's expedition from the start. Simpson wrote, "They do not feel free to share the details of their disastrous trip, and I fear they have not fully achieved their mission."

Simpson and other fur traders who knew the land criticized Franklin's poor planning. They also questioned his ability. They said he was unwilling to change his original plan. This was true even when it was clear that supplies and game would be too scarce. This showed his inflexibility and inability to adapt. If Franklin had more experience, he might have changed his goals. Or he might have stopped the expedition completely.

In a very harsh letter, Simpson also wrote about Franklin's physical weaknesses. He said Franklin "does not have the physical strength needed for moderate travel in this country." He added that Franklin "must have three meals a day, tea is essential, and with the most effort he cannot walk more than eight miles in one day." However, many fur traders did not want to help Franklin in the first place. Simpson, in particular, was angry. He saw Franklin as supporting the rival North West Company in their trade war.

When Franklin returned to England in October 1822, none of the rumors or criticism mattered. People overlooked the expedition's main failures. Instead, they admired his story of courage in hardship. Franklin had been made a commander while away. He was promoted to captain on November 20. He was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Back was made a lieutenant.

Franklin's account of the expedition was published in 1823. It was seen as a classic travel book. The publishing company could not keep up with demand. Second-hand copies sold for up to ten guineas. Ordinary people would point him out in the street. Remembering his desperate actions to avoid starvation, he became known as "the man who ate his boots."

Franklin made another expedition to the Arctic in 1825. With Richardson and Back, he traveled down the Mackenzie River. They mapped another part of Canada's coast. This time, the expedition was better organized. It relied less on outside help. All the main goals were met. After commanding ships outside the Arctic, and a difficult time as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, he led a final expedition in 1845. He wanted to discover the Northwest Passage. Franklin vanished almost without a trace. All 128 of his men were lost. The mystery of his fate is still not fully solved.

The story of the Coppermine Expedition influenced Roald Amundsen. He eventually became the first person to navigate the entire Northwest Passage. He was also the first to reach the South Pole. At fifteen, he read Franklin's account. He then decided he wanted to be a polar explorer.

|