Mackenzie River expedition facts for kids

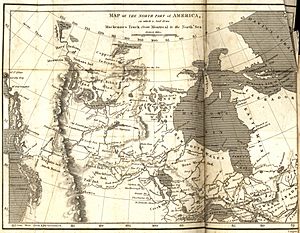

The Mackenzie River expedition (1825–1827) was an exciting journey into the Arctic led by explorer John Franklin. It was his second big trip for the Royal Navy. The main goal was to map the northern coast of North America. This area is now parts of Alaska, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut.

Franklin was joined by George Back and John Richardson. They had been with him on a tough earlier trip called the Coppermine expedition (1819–1821). Unlike that first trip, this one was very successful! They mapped over 1,000 km (620 miles) of new coastline. This was between the Coppermine River and Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Before this, Europeans had not explored much of this area.

Contents

Why Explore the Arctic?

For a long time, European explorers wanted to find the Northwest Passage. This was thought to be a sea route through the Arctic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. It would be a faster way to trade with places like East Asia. During the Age of Discovery, finding this passage was a big reason for exploring North America.

In the early 1800s, the Royal Navy became very powerful. They started focusing on finding this passage. A man named Sir John Barrow encouraged many Arctic expeditions. These included trips led by John Ross, William Edward Parry, James Clark Ross, and John Franklin. For about 50 years, the Royal Navy explored the Arctic seas.

John Franklin was an experienced sailor. He had joined the Royal Navy as a teenager. He even fought in the famous Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In 1819, he was chosen to lead an expedition to map the northern coast of North America. This trip, the Coppermine expedition, was very difficult. Franklin did not map enough of the coast, and half of his 22 men died.

Even with these tough results, Franklin was seen as a hero when he returned to Britain. He was promoted in 1822. The next year, he started planning another Arctic trip. This time, he planned to use the Mackenzie River as his main route.

Franklin himself planned the trip's route. The Admiralty (the British Navy's leaders) approved it in late 1823. His instructions said he should first travel to Great Bear Lake in the summer of 1825. This is where his group would build their winter home. In the spring of 1826, Franklin would go down the Mackenzie River to its mouth. There, he would split his group.

A smaller team, led by Richardson, would map the coast between the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. Franklin would travel west along the coast. His goal was to reach Icy Cape, a point in the Bering Sea. From there, Franklin could meet up with a ship called HMS Blossom. Or, he could return to their winter home, which became known as Fort Franklin (now Délı̨nę).

Getting Ready for the Journey

Franklin learned important lessons from his first difficult expedition. He realized that the Coppermine trip relied too much on outside help. His preparations were not finished early enough. He depended a lot on fur traders, voyageurs, and First Nations people. They were not as helpful as he had hoped.

For this new expedition, Franklin decided to trust British naval people more. Most importantly, he brought enough supplies for the whole journey. Also, the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company had recently joined together. This meant there was less fighting between them, so any help they offered would be more reliable.

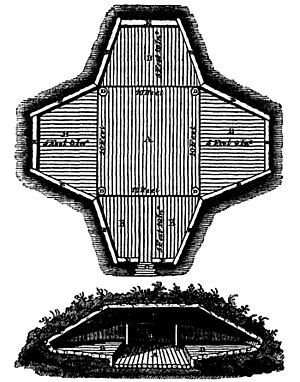

Supplies were sent from York Factory into the continent's interior starting in 1824. While still in Britain, Franklin watched over the building of the expedition's boats. Regular canoes made of birch bark were common for travel on North American rivers. But Franklin thought they were not strong enough for the open waters of the Arctic Ocean.

So, he ordered three special boats to be built. They were made of strong ash and mahogany wood. The largest boat was 8 meters (26 feet) long and could carry 2.7 tonnes (6,000 pounds) of gear. They brought navigation tools like a sextant, altimeters, and a telescope. Supplies included tobacco, tents, books, paper, fishing gear, blankets, clothes, guns, knives, and hatchets. Many supplies were meant for trading with local First Nations communities.

The Expedition Begins

Setting Off and the First Season

Franklin and the other naval officers, including Back and Richardson, left Liverpool on February 16, 1825. They arrived in New York City on March 15. Then, they followed common travel routes through New York, across the Niagara River and Lake Ontario. They continued through Upper Canada to Fort William on Lake Superior.

After crossing many lakes and rivers, the group reached Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River on June 15. From there, they got to Methye Portage, mostly by way of the Churchill River system. At the same time, most of the expedition's supplies were sent from York Factory on Hudson Bay. These supplies came up the Hayes River and met the officers at Methye Portage on June 29.

The group went down the Clearwater and Athabasca Rivers. They arrived at Fort Chipewyan on July 15. They moved very quickly because they rowed intensely. For example, during their last push to Great Slave Lake, they had been paddling for 36 out of 39 hours!

At Fort Resolution, Franklin met with Keskarrah, the older brother of his friend Akaitcho. He also met Humpy of the Yellowknives (Coppermine Indians). After traveling along the southern shore of Great Slave Lake, the group reached the start of the Mackenzie River on August 3. This river would be their path to the Arctic Ocean.

The group began their journey down the Mackenzie River. They reached its meeting point with the "River of the Mountains" (likely the Liard River) on August 4. Fort Norman (now Tulita) was reached on August 7. They had traveled 423 km (263 miles) in just three days. At Fort Norman, Franklin realized they had extra time because of their fast pace. He decided to make a quick trip to the mouth of the Mackenzie River. The rest of the group would continue to Great Bear Lake to build their winter home.

The goal of this quick trip was to find the best route to the sea. It was also to make friends with the local Inuit people. Franklin was joined by assistant surveyor Edward Nicholas Kendall and an Inuk interpreter. They left on August 8.

During their trip down the river, they met several groups of First Nations people. Some joined them for part of the journey. They reached the delta (mouth) of the Mackenzie River on August 13. After that, they started exploring the many islands around the river's mouth. Thick fog often made it hard to see the stars for navigation. After finishing their early mapping, the group returned to the Mackenzie River. They reached Fort Franklin (modern-day Délı̨nę) on Great Bear Lake on September 5. During the 1825 season, the group had traveled 9,339 km (5,803 miles).

Winter at Fort Franklin

The winter of 1825–1826 was mostly calm. On September 8, Franklin sent two men to Great Slave Lake. They were to report on the expedition's progress and pick up letters from the Crown. The Chipewyan and Dog-Rib Indians provided supplies. In October, the first frosts and snow arrived. This was the best time for fishing, just before the lake froze. Franklin reported that hundreds of fish were caught daily. Most were frozen to be eaten later in the spring.

The people at Fort Franklin often had visitors from the local First Nations. For example, on December 18, the wife of a Dog-Rib hunter brought her young, sick girl to the fort. Even with the Europeans' help, the girl died. This caused great sadness for the mother. The First Nations and Europeans celebrated Christmas together on December 25. On January 1, the coldest temperature of the season was recorded: -45°C (-49°F). February brought worry to the group as their fishing catches dropped a lot. Their dried meat was gone, and eating only fish made several people sick with diarrhea.

Franklin's journal mentions that during the winter of 1825–1826, the men played a game similar to modern ice hockey to pass the time. In another note, Franklin said "skating" was one of the winter "amusements." It's not known if they combined skating with the game. If they did, Fort Franklin (Délı̨nę) would be the earliest place where ice hockey was played. It would also be the first known use of the word "hockey" for the sport we know today.

The ice on Great Bear Lake started to break up on May 23. But with this came lots of mosquitoes, which Franklin called "vigorous and tormenting." As winter ended, the group worked more on mapping the coastline of Great Bear Lake. Richardson and Kendall did the longest of these explorations, from April 10 to May 1. Franklin became annoyed with the constant presence of the Dog-Rib Indians. He wrote that their "daily drumming and singing over the sick, the squalling of the children, and bawling of the men and women, proved no small annoyance." In early June, Franklin began planning the group's trip to the coast more intensely. The boats they had built over the winter were tested on June 15. Supplies and men were then divided between the western and eastern groups. After final preparations, they left Fort Franklin on the summer solstice of 1826.

Spring and Splitting Up

The expedition's plans for the summer were big. Franklin, leading the western group, aimed to reach Icy Cape. This place had been visited by James Cook in 1778. Richardson's journey would involve traveling along the ocean shore as far east as the mouth of the Coppermine River. He would then go up that river and travel overland to Great Bear Lake. The goal was to arrive at Fort Franklin before winter.

The group quickly went down the Mackenzie River, reaching its delta by early July. The western group would have two boats, Lion and Reliance, led by Franklin and Back. The eastern group had the boats Dolphin and Union, which are remembered in the Dolphin and Union Strait. In the early morning of July 4, the groups split up.

Western Journey

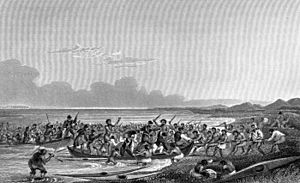

The western group quickly ran into trouble with the Inuit. When their boats got stuck in shallow water, Franklin saw an Inuit settlement nearby. He told Back and the others to be ready to defend themselves if the Inuit were unfriendly. Franklin then went to the camp with the interpreter, Tattannoeuck (Augustus). The settlement had over 250 people. At first, they were unsure about the explorers. When Franklin explained how the sea route (the Northwest Passage) could help their people, they became friendly.

Soon after, however, the Inuit wanted the group's cargo. They took items from Lion and Reliance. After a conflict that lasted several hours, Tattannoeuck, who had gone ashore, returned. The tide rose, and the two boats left. Franklin ordered that no Inuit follow them, or they would be shot. He later named the area where the conflict happened Pillage Point.

For the rest of the season, bad weather and sea ice often slowed the group's journey. On July 9, the group met the Inuit again. This time, the meeting was much friendlier. Franklin asked about when the ice usually broke up, and the groups exchanged gifts. Franklin noted that this Inuit group, with 48 people, had many elders. All of them were very active and seemed healthy. Nearly all suffered from some snowblindness. When told about the Europeans' earlier conflict, these Inuit said the attack was wrong.

On July 15, they reached the mouth of the Babbage River. Soon after, Herschel Island came into view. On July 17, the group landed on the island and met more Inuit. Traveling west along the Arctic coast was hard. Temperatures were rarely above 6°C (43°F). Strong winds often blew down the explorers' tents, making it hard to stay dry from the rain. Constant fog made it hard to see, and Franklin described the mosquitoes as "torturous." At one point, Tattannoeuck (Augustus) got hypothermia after rushing into an icy lake to chase a reindeer. He was given blankets and chocolate to warm up, but still felt pain the next morning.

By July 30, the group had entered the waters of modern-day Alaska. Brownlow Point was reached on August 5. In the following weeks, Franklin hesitated to keep going towards Icy Cape. On August 16, he realized summer was ending. The route would become too dangerous due to worsening conditions. Franklin decided they would turn back towards the Mackenzie's mouth.

He did not know that an exploration party from Beechey's ship was only 257 km (160 miles) to the west. At their average speed, they could have reached them in less than a week. Franklin later wrote that if he had known Beechey's ship was only six days away, "no difficulties, dangers, or discouraging circumstances, should have [prevented]" him from meeting Beechey. But he did not know, so he chose to return to the Mackenzie.

The journey east was mostly calm. However, sea ice and wind continued to be a serious threat. The group landed on Herschel Island again on August 26. They met Inuit almost daily. On August 29, a group of Inuit told Franklin that Richardson's group had been seen leaving the Mackenzie River delta. They had barely escaped another attempt by the Inuit to take their boats.

Franklin was later alarmed by a group of Inuit who rushed into their camp. They told him that a rival Inuit group was coming to attack them and steal their belongings. This group, called the 'Mountain Indians' by Franklin, supposedly planned to wait for their return to the Mackenzie River mouth. Pretending to help the Europeans navigate, the Mountain Indians would then damage their boats. This would stop them from escaping to deeper waters. Then, a larger group would rush out of a hiding spot and attack. The Inuit warned Franklin to only camp on islands that were out of gunshot range. He later guessed that the Mountain Indians had gotten weapons from trading with Russians. Russians were supposedly not allowed to trade with Inuit groups.

By September, the group was going up the Mackenzie River. On September 4, they reached Point Separation, where the two groups had originally split. They found a small supply hidden there in July before continuing. The mouth of the Great Bear River was reached on September 16. Five days later, they arrived back at Fort Franklin. During their journey, the western group had traveled a total distance of 3,296 km (2,048 miles) in 80 days. This was an average of about 41 km (25 miles) per day.

Eastern Journey

The eastern group had twelve people. They went down the Mackenzie River and eventually reached the open ocean. Their meetings with the Inuit were mostly friendly. Their Inuit companion, Ooligbuck, helped with talking to them.

After going through the many islands of the Mackenzie delta, they reached the open sea on July 7. That same day, they met a group of Inuit. Richardson calmed their initial fears by giving gifts. He started talking with the group, but found them a bit rude. Ooligbuck, who seemed to distrust the group, urged Richardson to leave. When they did, the Inuit followed them. These encounters continued almost constantly until July 20. That was the last time they saw Inuit before reaching the Coppermine River.

The next few days were spent going around the very bumpy coastline. Sea ice often slowed their progress. On August 4, a large landmass to the north came into view. Richardson called it Wollaston Land. This land was actually a southern part of Victoria Island. This is the second largest island in the Arctic Archipelago. This was the first time a European had seen the island. Coronation Gulf was reached on August 6. From there, the group turned south until they reached the mouth of the Coppermine. At this point, Richardson entered territory that Franklin had already mapped on his previous expedition.

The group reached the mouth of the Coppermine River on August 8. The next day, they started going up the river. The river was very low at that point. Sometimes, it was so low that it stopped their boats. After passing Bloody Falls, Richardson decided that the rest of the Coppermine River was too hard to travel by boat. So, he decided to leave Dolphin and Union behind. The group would continue on foot.

Each man was given 9 kg (20 pounds) of pemmican. They also had packages of macaroni, dry soup mix, chocolate, sugar, and tea. In addition, the group carried a portable boat, blankets, extra guns, shoes, ammunition, fishing nets, kettles, and hatchets. When divided among the group, this load weighed 33 kg (73 pounds) per man. Richardson worried that carrying so much weight would be too hard. He promised the men that once they made good progress, they would stop and decide if they needed to carry certain items. Everything not carried by the group was stored in tents marked with a Union Jack. This was for any future explorers to use.

The walk to Great Bear Lake began on August 10. Richardson planned to follow the Coppermine as far as its meeting point with the Copper Mountains. From there, they would hike mostly in a straight line until they reached the Dease River. They would then go down this river to its mouth at Great Bear Lake. Many in the group were not used to carrying such heavy loads. But after checking their supplies, Richardson found little that he thought was unnecessary enough to throw away. He eventually decided to leave the portable boat and five of the group's rifles. This reduced each man's load by 7 kg (15 pounds). Still, the group rarely walked faster than 3 km/h (1.9 mph).

Even with lighter loads, many in the group were tired by the end of each day. Richardson said much of their tiredness came from the frequent changes in elevation and the soft, wet ground. This made it hard to walk steadily. The group got more used to their loads in the following days and soon walked at a better speed.

On the night of August 15, the group met some First Nations people. They led them to the start of the Dease River. Soon after, a range of hills unique to the north shore of Great Bear Lake came into view. The lake itself was spotted on August 18. From that point on, Richardson was to wait for a scout from Fort Franklin. This scout had been told to leave the fort on August 6 and wait at the mouth of the Dease River for Richardson's group. After sending out hunting trips to get more food for their push to Fort Franklin, Richardson and the scouting party met on August 21. After paddling along the coast of Great Bear Lake, they reached Fort Franklin on September 1. This was almost two weeks before the western group arrived.

The eastern group had traveled 3,197 km (1,987 miles) over 60 days. This was an average of about 53 km (33 miles) per day. A total of 1,452 km (902 miles) of new coastline had been mapped during their journey.

Second Winter and Leaving

While the groups were away from Fort Franklin, those who stayed were told to make repairs. These were finished by the time Franklin arrived. However, when he got there, Franklin was worried about how little food was left. He sent Kendall to get more food and supplies from Fort Norman. Kendall returned to the fort on October 8. He brought lots of food and other supplies. These were especially helpful for the eastern group, who had to leave much of their equipment during their overland trip between the Coppermine and Dease Rivers.

The group's second winter had few important events. By mid-November, the ice on Great Bear Lake made it impossible to travel by boat. By early January, temperatures dropped to -47°C (-53°F), and by February, to -50°C (-58°F). The fort's food storage at that point had tens of thousands of fish and nearly 11 tonnes (24,000 pounds) of meat. Franklin planned to leave the fort much earlier than the previous season. He left the fort on February 20. He carried most of his supplies, including all the expedition's maps, journals, and drawings, on a sled. Back was to stay at the fort until the ice broke up. After that, he would go to York Factory and then to England on a Hudson's Bay Company ship.

Franklin and his group traveled south through the taiga (boreal forest). They arrived at Fort Chipewyan on April 12 and then Cumberland House on June 18. It was there that Franklin and Tattannoeuck (Augustus) said goodbye. Tattannoeuck cried when they parted. He asked to be told about any other Arctic expeditions he could join. They reached New York in August. On September 1, Franklin left North America on a packet ship going to Liverpool. He arrived on September 26. Back and the other officers arrived in Britain in October. Franklin's second expedition had now ended.

What Happened Next

When Franklin returned to Britain, he was celebrated as a hero. In 1829, George IV made him a knight. He later received other important awards. Although Back had been made a commander in 1825, he could not find a job on a ship after returning to Britain. He was unemployed until 1833.

During the expedition, Franklin and his team traveled nearly 22,000 km (13,700 miles). They mapped half of North America's northern coast. This was a huge improvement from Franklin's previous expedition. On that trip, only 800 km (500 miles) had been explored before they had to turn back.

Franklin himself later wrote about how different this expedition was from his first one. When the group split at Point Separation, he realized the big change. He wrote that "it was impossible not to be struck with the difference between our present complete state of equipment and that on which we had embarked on our former disastrous voyage. Instead of a frail bark canoe, and a scanty supply of food, we were now about to commence the sea voyage in excellent boats, stored with three months' provision."

Franklin was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) in 1837. He left this job after six years. Less than 500 km (310 miles) of Arctic coastline remained unmapped. So, Franklin, who was then 59 years old, was chosen to lead another expedition in 1845. The Northwest Passage expedition left England in 1845 on the ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. In the autumn of 1846, the ships got stuck in ice somewhere in Victoria Strait. Franklin and all 128 of his men were lost.

During the Navy's investigation into Franklin's lost expedition, several search parties were sent out. Back was part of this investigation. All the searches were unsuccessful. The wrecks of Erebus and Terror were found off King William Island in 2014 and 2016.

Earlier Discoveries

Before Franklin's second expedition, Europeans had only seen the mouth of the Mackenzie River once. In 1789, Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie traveled down the river. He hoped it would lead to the Pacific Ocean. Working for the North West Company, Mackenzie spent the summer of 1789 going down the river. He reached its mouth on July 14. Mackenzie was disappointed because he had reached the wrong ocean. He turned back and returned to Britain, where his efforts were not widely recognized. Mackenzie later led the first overland crossing of North America, reaching the western coast of British Columbia in 1793.

In 1771, Samuel Hearne traveled overland from Hudson Bay. He reached the source of the Coppermine River in July. He went down the river to Coronation Gulf. This was the first time a European had reached the Arctic Ocean by land.

During his third voyage, James Cook mapped much of the western coast of North America. This included Alaska's Cook Inlet. He reached Icy Cape, Franklin's final goal for the western group, in August 1778. Cook named it Icy Cape because of the large amounts of ice along its coast.

See also

- Arctic exploration

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |