Crawford expedition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Crawford expedition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Ohio Country Natives Great Britain |

U.S. volunteers (mostly Pennsylvania militia) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William Caldwell (WIA) Captain Pipe (Lenape) Dunquat (Wyandot) Matthew Elliott Black Snake (Shawnee) Alexander McKee |

William Crawford † David Williamson Thomas Gaddis John B. McClelland † Gustave Rosenthal James Brenton (WIA) John Hardin |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 340–640 Natives 100 British rangers |

500+ mounted militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 killed 10–11 wounded |

fewer than 70 killed, including executed prisoners | ||||||

The Crawford expedition, also known as the Sandusky expedition, was a military journey in 1782. It happened during the American Revolutionary War on the western frontier. This was one of the last big actions of the war.

Colonel William Crawford, a former U.S. Army officer, led the expedition. His goal was to destroy Native American towns along the Sandusky River in Ohio Country. He hoped this would stop Native attacks on American settlers. Both sides had been raiding each other's settlements throughout the war.

In May 1782, Crawford led about 500 volunteer soldiers, mostly from Pennsylvania. They went deep into Native American lands to surprise their enemies. However, the Natives and their British allies from Detroit found out about the plan. They gathered a strong force to stop the Americans.

On June 4, a day of fighting happened near the Sandusky towns. The Americans found safety in a group of trees called "Battle Island." More Native and British fighters arrived the next day. The Americans found themselves surrounded and decided to retreat that night. The retreat became very messy, and Colonel Crawford got separated from most of his men. About 70 Americans were killed or captured, while the Native and British forces had very few losses.

During the retreat, Crawford and some of his men were captured. The Natives carried out harsh actions against many of these prisoners. This was in response to a terrible event earlier that year. In that event, about 100 peaceful Natives were killed by Pennsylvanian soldiers in what is known as the Gnadenhütten massacre. Colonel Crawford's death was particularly harsh. News of his death spread widely in the United States. This made the already difficult relationship between Natives and Americans even worse.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

The Ohio Country Border Dispute

When the American Revolutionary War started in 1775, the Ohio River was a shaky border. It separated the American colonies from the Native peoples of the Ohio Country. Native groups like the Shawnees, Mingos, Lenapes (Delawares), and Wyandots had different ideas about the war. Some leaders wanted to stay neutral. Others joined the fight. They saw it as a chance to stop American expansion and get back lands they had lost.

Escalating Frontier Conflict

The border fighting got worse in 1777. British officials in Detroit began giving weapons to Native war parties. These groups then raided American settlements on the frontier. Many American settlers in what is now Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania were killed. The conflict grew even more intense in November 1777. American soldiers killed Cornstalk, a Shawnee leader who wanted peace. Even with this violence, many Ohio Natives still hoped to stay out of the war. But it was hard because they were stuck between the British in Detroit and the Americans along the Ohio River.

Early American Expeditions

In 1778, Americans launched their first trip into the Ohio Country. General Edward Hand led 500 Pennsylvania soldiers from Fort Pitt. They hoped to surprise British supply areas. Bad weather stopped them from reaching their goal. On their way back, some of Hand's men attacked peaceful Lenapes. They killed a man, women, and children. This included relatives of the Lenape chief Captain Pipe (Hopocan). Because only non-fighters were killed, this trip was sometimes called the "squaw campaign."

Despite the attack on his family, Captain Pipe said he would not seek revenge. In September 1778, he signed the Treaty of Fort Pitt with the United States. Americans hoped this treaty would let their soldiers pass through Lenape land to attack Detroit. But the alliance fell apart after White Eyes, the Lenape chief who made the treaty, died. Captain Pipe eventually turned against the Americans. He moved his followers west to the Sandusky River. There, he got support from the British in Detroit.

Raids and Retaliation on the Frontier

Over the next few years, Americans and Natives raided each other's settlements. In 1780, hundreds of Kentucky settlers were killed or captured. This happened during a British-Native trip into Kentucky. George Rogers Clark of Virginia responded in August 1780. He led a trip that destroyed two Shawnee towns. But it did not do much damage to the Native war effort.

Most Lenapes had become pro-British by then. So, American Colonel Daniel Brodhead led a trip into the Ohio Country in April 1781. He destroyed the Lenape town of Coshocton. Clark then tried to gather men for a trip against Detroit in the summer of 1781. But Natives strongly defeated 100 of his men along the Ohio River. This ended his campaign. Survivors fled to the fighting towns on the Sandusky River.

The Gnadenhütten Massacre

Several villages of Christian Lenapes were located between the fighting groups. These villages were on the Sandusky River and near the Americans at Fort Pitt. Moravian missionaries David Zeisberger and John Heckewelder ran the villages. The missionaries were peaceful, but they supported the American side. They kept American officials at Fort Pitt informed about British and Native actions. In September 1781, hostile Wyandots and Lenapes from Sandusky moved the missionaries and their followers. They were taken to a new village called Captive Town on the Sandusky River. This was done to stop them from sharing information.

In March 1782, nearly 200 Pennsylvania soldiers rode into the Ohio Country. They were led by Lieutenant Colonel David Williamson. They hoped to rescue American captives and find warriors who had raided Pennsylvania. Williamson's men captured about 100 Christian Lenapes at Gnadenhütten. These Christian Lenapes (mostly women and children) had returned to harvest their crops. The Pennsylvanians accused them of helping hostile raiding parties. They then killed all of them. This event, called the Gnadenhütten massacre, would have serious effects.

When George Washington, the American commander, heard about the Gnadenhütten massacre, he warned his soldiers. He told them not to let themselves be captured alive by Natives. But by then, the Sandusky expedition had already started.

Planning the Expedition

In September 1781, General William Irvine became commander of the Western Department of the Continental Army. His headquarters were at Fort Pitt. A major British army had surrendered at Yorktown in October 1781. This mostly ended the war in the east. But fighting continued on the western frontier. Irvine learned that frontier Americans wanted the army to attack Detroit. They hoped this would end British support for Native war parties.

Irvine looked into it and wrote to Washington on December 2, 1781. He said: "It is, I believe, universally agreed that the only way to keep Indians from harassing the country is to visit them. But we find, by experience, that burning their empty towns has not the desired effect. They can soon build others. They must be followed up and beaten, or the British, whom they draw their support from, totally driven out of their country. I believe if Detroit was demolished, it would be a good step toward giving some, at least, temporary ease to this country."

Washington agreed that Detroit needed to be captured or destroyed. This would end the war in the west. In February 1782, Irvine sent Washington a detailed plan for an attack. Irvine thought he could capture Detroit with 2,000 men, five cannons, and supplies. Washington replied that the U.S. Congress did not have money for such a large campaign. He wrote that "offensive operations, except upon a small scale, can not just now be brought into contemplation."

Since Congress and the army had no money, Irvine let volunteers organize their own attack. Detroit was too far and too strong for a small group. But soldiers like David Williamson thought a trip against the Native towns on the Sandusky River was possible. This would be a low-cost effort. Each volunteer had to bring their own horse, rifle, ammunition, food, and other gear. Their only payment would be two months off from militia duty. They could also keep any items taken from the Natives. Native raids were still happening. For example, a minister's wife and children were killed in Pennsylvania on May 12, 1782. So, many men were willing to volunteer.

Irvine believed he was not allowed to lead the expedition himself. But he helped plan it. He wrote detailed instructions for the commander, who had not yet been chosen. He stated the goal was "to destroy with fire and sword (if practicable) the Indian town and settlement at Sandusky." This was to bring peace to the country.

Organizing the Expedition

On May 20, 1782, volunteers started gathering at Mingo Bottom. This was on the Native side of the Ohio River. Most were young men of Irish and Scots-Irish background. They came mainly from Washington and Westmoreland counties in Pennsylvania. Many were veterans of the Continental Army. Many had also been part of the Gnadenhütten massacre.

The exact number of men is not known. An officer wrote on May 24 that there were 480 volunteers. More men might have joined later. One historian, Parker Brown, thought as many as 583 men might have taken part. But some left before reaching Sandusky. The task ahead was dangerous. Many volunteers wrote their "last wills and testaments" before leaving.

This was a volunteer trip, not a regular army operation. So, the men elected their leaders. The main choices for commander were David Williamson and William Crawford. Williamson was the militia colonel who led the Gnadenhütten trip. Crawford was an experienced soldier who had left the Continental Army in 1781. Crawford was a longtime friend of George Washington. He had experience with these kinds of operations. In Lord Dunmore's War (1774), he destroyed a Mingo village. In 1778, he was part of the failed "squaw campaign." Crawford, nearly 60 years old, did not want to volunteer. But he did so at Irvine's request.

Williamson was popular with the militia. But Irvine wanted Crawford to be elected. He hoped to avoid another event like the Gnadenhütten massacre. Irvine knew many people in western Pennsylvania disliked Continental Army officers. He wrote, "The general and common opinion of the people of this country is that all Continental officers are too fond of Indians." The election was heated and close. Crawford got 235 votes to Williamson's 230. Colonel Crawford took command. Williamson became second-in-command as a major. Other majors included John B. McClelland, Thomas Gaddis, and James Brenton.

Crawford asked Irvine to let Dr. John Knight, an army officer, join as a surgeon. Another volunteer from Irvine's staff was a foreigner named "John Rose." He was Crawford's assistant. Rose was actually Baron Gustave Rosenthal, a nobleman from the Russian empire. He had fled to America after a duel. Rosenthal is the only Russian known to have fought for the Americans in the Revolutionary War. He kept a detailed journal of the trip. This was likely to help him write a report for Irvine.

Journey to the Sandusky River

Crawford's volunteers left Mingo Bottom on May 25, 1782. They carried food for 30 days. General Irvine had thought the 175-mile (282 km) journey to Sandusky would take seven days. The trip started with high hopes. Some volunteers even said they wanted "to extermenate the whole Wiandott Tribe."

It was hard to keep military order, as often happens with volunteer soldiers. The men wasted their food. They often fired their guns at wild animals, even though they were told not to. They were slow to leave camp in the mornings. They often did not take their turn guarding. Crawford also was not as good a leader as expected. Rose wrote that Crawford spoke "incoherent, proposes matters confusedly, and is incapable of persuading people into his opinion." The expedition often stopped as leaders argued about what to do. Some volunteers lost hope and left.

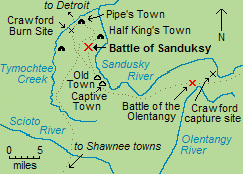

The journey through the Ohio Country was mostly through forests. The volunteers first marched in four lines. But the thick bushes sometimes made them form just two lines. On June 3, Crawford's men came out into the open area of the Sandusky Plains. This was a grassy region just below the Sandusky River. The next day, June 4, they reached Upper Sandusky. This was the Wyandot village where they expected to find the enemy. But they found it had been left empty. The Americans did not know that the Wyandots had moved their town eight miles (13 km) north. The new Upper Sandusky, also called "Half King's Town," was near present-day Upper Sandusky, Ohio. It was also close to Captain Pipe's Town (near present-day Carey, Ohio). The Americans did not know Pipe's Town was nearby.

Crawford's officers held a meeting. Some argued that the empty village meant the Natives knew about the expedition. They thought the Natives were gathering their forces elsewhere. Others wanted to stop the trip and go home right away. Williamson asked to take 50 men and burn the empty village. But Crawford refused because he did not want to split his force. The group decided to keep marching for the rest of the day, but then stop. As they paused for lunch, John Rose went north with a scouting party. Soon, two men returned. They reported that the scouts were fighting a large group of Natives who were moving towards the Americans. The Battle of Sandusky had begun.

British and Native Preparations

Learning of the American Plan

When planning the expedition, General Irvine told Crawford, "Your best chance of success will be, if possible, to effect a surprise" against Sandusky. However, the British and Natives knew about the expedition even before Crawford's army left Mingo Bottom. Thanks to information from a captured American soldier, British agent Simon Girty sent a detailed report of Crawford's plans to Detroit on April 8.

Gathering Forces

Officials of the British Indian Department in Detroit got ready for action. Major Arent DePeyster was in command at Detroit. He reported to Sir Frederick Haldimand, the Governor General of British North America. DePeyster used agents like Girty, Alexander McKee, and Matthew Elliott. These agents had close ties with Natives. They helped coordinate British and Native military actions in the Ohio Country.

In a meeting at Detroit on May 15, DePeyster and McKee told Native leaders about the Sandusky expedition. They advised them to "be ready to meet them in a great body and repulse them." McKee was sent to the Shawnee villages to recruit warriors. Captain William Caldwell was sent to Sandusky with a company of mounted Butler's Rangers. He also brought Natives from the Detroit area, led by Matthew Elliott. These Natives were called "Lake Indians" by the British. They included the "Three Fires Confederacy" and northern Wyandots.

Native Scouts and Positions

Native scouts watched the expedition from the start. As soon as Crawford's army moved into the Ohio Country, a warning was sent to Sandusky. As the Americans got closer, women and children from the Wyandot and Lenape towns were hidden in nearby ravines. British fur traders packed their goods and quickly left town. On June 4, Lenapes under Captain Pipe and Wyandots under Dunquat, the "Half King," joined forces. Some Mingos also joined them to fight the Americans. The combined force of Lenape, Wyandot, and Mingo warriors was estimated to be between 200 and 500 or more. British reinforcements were nearby. Shawnees from the south were expected to arrive the next day. When the American scouts appeared, Pipe's Lenapes chased them. The Wyandots held back for a short time.

Battle of Sandusky

June 4: Fighting at "Battle Island"

The first fighting of the Crawford expedition began around 2 p.m. on June 4, 1782. The scouting party led by John Rose met Captain Pipe's Lenapes on the Sandusky plains. They fought as they retreated to a group of trees where their supplies were. The scouts were in danger of being overwhelmed. But they were soon joined by the main part of Crawford's army. Crawford ordered his men to get off their horses and push the Natives out of the woods. After intense fighting, the Americans took control of the group of trees. This place later became known as "Battle Island."

The skirmish became a full battle by 4:00 p.m. After the Americans pushed Captain Pipe's Lenapes out of the woods and onto the prairie, Dunquat's Wyandots joined the Lenapes. British agent Matthew Elliott might have been there, helping to organize the Lenape and Wyandot actions. Pipe's Lenapes cleverly went around the American position and then attacked their rear. A few Natives crawled close to the American lines in the tall prairie grass. The Americans climbed trees to get a better shot at them. Gunsmoke filled the air, making it hard to see. After three and a half hours of constant firing, the Natives slowly stopped their attack as night came. Both sides slept ready to fight. They built large fires around their positions to prevent surprise night attacks.

On the first day of fighting, the Americans had 5 men killed and 19 wounded. The British and Natives had 5 killed and 11 wounded. The British and Natives had a setback early in the battle. William Caldwell, the British rangers' commander, was wounded in both legs. He had to leave the field. Fifteen Pennsylvanians left during the night. They went home and reported that Crawford's army had been "cut to pieces."

June 5: Shawnee Reinforcements and American Retreat

Firing started early on the morning of June 5. The Natives stayed about two or three hundred yards away. Such long-range firing with smooth-bore muskets caused little harm to either side. The Americans thought the Natives were holding back because they had lost many fighters the day before. But the Natives were actually waiting for more fighters to arrive. Crawford decided to stay in the trees and make a surprise attack on the Natives after dark. At this point, he still felt confident. But his men were low on ammunition and water. Simon Girty, the British agent and interpreter, rode up with a white flag. He called for the Americans to surrender, but they refused.

That afternoon, the Americans finally noticed about 100 British rangers fighting with the Natives. The Americans were surprised that British troops from Detroit had joined the battle so quickly. They did not know the expedition had been watched from the beginning. While the Americans were talking about this, Alexander McKee arrived. He brought about 140 Shawnees led by Black Snake (Peteusha). They took a position to Crawford's south, surrounding the Americans. The Shawnees repeatedly fired their muskets into the air. This was a ceremonial show of strength called a feu de joie ("fire of joy"). It lowered American spirits. Rose recalled that the feu de joie "completed the Business with us."

With so many enemies gathering, the Americans decided to retreat after dark. They would not make a stand. The dead were buried. Fires were burned over the graves to hide them. The badly wounded were placed on stretchers for the withdrawal.

That night, the Americans began to leave the battlefield. The plan was to go back the same way they came. Major McClelland's group would lead. When Crawford learned that men under Captain John Hardin had already left, he stopped the retreat. He rode after Hardin's men, hoping to bring them back in line. He was too late. Native guards fired on Hardin's men, causing panic. McClelland's men rushed forward, leaving McClelland behind. Many Americans got lost in the dark, splitting into small groups. When Major Brenton was wounded, Major Daniel Leet took command of his group. He led about 90 men, including John Crawford (the colonel's son), to the west. They managed to escape and eventually returned home.

In the confusion, Crawford worried about his family. His son John, his son-in-law William Harrison, and his nephew, also named William Crawford, were missing. With Dr. Knight, Crawford stayed in the area as his men passed. He called for his missing relatives but did not find them. Crawford became angry when he realized the soldiers had left some wounded behind, despite his orders. After all the men had passed, Crawford and Knight, with two others, finally left. But they could not find the main group of men.

June 6: Battle of the Olentangy

When the sun rose on June 6, 250 to 300 Americans had reached the empty Wyandot town. Colonel Crawford was missing, so Williamson took command. Luckily for the Americans, the chase of the retreating army was disorganized. Caldwell, the overall commander of the British and Native forces, had been wounded early in the battle. Caldwell believed none of the Americans would have escaped if he had still been present.

As the retreat continued, a group of Natives finally caught up with the main American force. This was on the eastern edge of the Sandusky Plains, near a branch of the Olentangy River. Some Americans fled when the attack began. Others were confused. Williamson made a stand with a small group of volunteers. They drove off the Natives after an hour of fighting. Three Americans were killed and eight more wounded in the "Battle of the Olentangy." Native losses are not known.

The Americans buried their dead and continued their retreat. The Natives and British rangers chased them, firing sometimes from far away. Williamson and Rose kept most of the men together. They warned them that an orderly retreat was their only chance to get home alive. The Americans fell back more than 30 miles (48 km), some on foot, before making camp. The next day, two American stragglers were captured and likely killed. Then the Natives and rangers finally stopped the chase. The main group of Americans reached Mingo Bottom on June 13. Many stragglers arrived in small groups for several more days.

Fates of the Captured Americans

Natives sometimes captured people during the American Revolution. These captives might be exchanged for money by the British in Detroit. They might be welcomed into the tribe. Or they might be killed. The number of American prisoners killed after the Sandusky expedition is not fully known. Their fate was usually recorded only if someone survived to tell the story.

Shawnee Prisoners

During the June 5 retreat, an American scout named John Slover ran eastward with a small group of soldiers. He and two others were captured on June 8. They were taken to Wakatomika, a Shawnee town. This town was on the Mad River, in present Logan County, Ohio. One of Slover's friends was painted black by the Shawnees. This was a sign that he would be killed.

The villagers knew prisoners were coming. They formed two lines. The three prisoners were made to run between the lines towards the council house. This was about 300 yards (274 m) away. As the prisoners ran, the villagers hit them with clubs. They focused on the one who had been painted black.

While at Wakatomika, Slover saw the remains of three other Americans. They had recently faced the same fate. These were Major McClelland, who was fourth in command of the expedition. Also, Private William Crawford (Colonel Crawford's nephew) and William Harrison (Crawford's son-in-law). Slover was taken to Mac-a-chack. But he escaped before he could be burned. He stole a horse and rode it until it was too tired. Then he ran on foot. He reached Fort Pitt on July 10. He was one of the last survivors to return.

Aftermath of the Expedition

Casualties and Losses

The exact number of people killed or wounded in the Crawford expedition is not known. On June 7, 1782, a British ranger reported to DePeyster. He said, "Our loss is very inconsiderable. We had but one ranger killed and two wounded [including Caldwell]. LeVillier, the interpreter, and four Indians were killed and eight wounded. The loss of the enemy is one hundred killed and fifty wounded." British estimates of American losses were too high.

Historian Consul W. Butterfield, who wrote a book about the expedition, estimated that fewer than 70 Americans were killed. This included captured prisoners who were killed. Historian Parker Brown found the names of 41 Americans who were killed (including prisoners). He also found 17 who were wounded. And 7 who were captured but later escaped or were set free. He noted that his list was probably not complete.

The "Bloody Year" on the Frontier

The failure of the Crawford expedition worried people on the American frontier. Many Americans feared the Natives would feel stronger and launch new raids. More defeats for the Americans were still to come. So, for Americans west of the Appalachian Mountains, 1782 became known as the "Bloody Year."

On July 13, 1782, the Mingo leader Guyasuta led about 100 Natives and some British volunteers into Pennsylvania. They destroyed Hannastown. They killed nine settlers and captured twelve. This was the hardest blow by Natives in Western Pennsylvania during the war.

In Kentucky, the Americans went on the defensive. Caldwell and his Native allies prepared a major attack. In July 1782, more than 1,000 Natives gathered at Wakatomika. But the expedition stopped. Scouts reported that George Rogers Clark was getting ready to invade the Ohio Country from Kentucky. Most of the Natives left after learning that the reports of invasion were false. But Caldwell led 300 Natives into Kentucky. They delivered a strong blow at the Battle of Blue Licks in August.

After his victory at Blue Licks, Caldwell was told to stop fighting. This was because the United States and Great Britain were about to make peace. Irvine had finally gotten permission to lead his own expedition into the Ohio Country. But rumors of the peace treaty ended interest in the plan. It never happened. In November 1782, George Rogers Clark delivered the final blow in the Ohio Country. He destroyed several Shawnee towns. But he did little harm to the people living there.

Details of the coming peace treaty arrived late in 1782. The Ohio Country, which the British and Natives had successfully defended, was given to the United States by Great Britain. The British had not talked to the Natives during the peace process. The Natives were not mentioned in the treaty's terms at all. For the Natives, the fight with American settlers would start again in the Northwest Indian War. But this time, they would not have help from their British allies.

Impact of Crawford's Death

News of Crawford's death spread widely in the United States. A popular song about the expedition, called "Crawford's Defeat by the Indians", was remembered in many versions. In 1783, John Knight's eyewitness story of Crawford's death was published. So was Slover's captivity narrative. They appeared in Francis Bailey's Freeman's Journal and in a separate booklet.

Knight's editor, Hugh Henry Brackenridge, disliked Natives. He changed Knight's story. He removed parts about Crawford's trial. He also removed the fact that Crawford was killed in response to the Gnadenhütten massacre. By hiding the Natives' reasons, Brackenridge created "a piece of virulent anti-Indian, anti-British propaganda." This was meant to stir up public attention and patriotism. Brackenridge called for all Native Americans to be removed or killed. He also wanted their lands taken. In an introduction to the stories, Bailey supported this idea:

"But as they [the Natives] still continue their murders on our frontier, these Narratives may be serviceable to induce our government to take some effectual steps to chastise and suppress them; as from hence, they will see that the nature of an Indian is fierce and cruel, and that an extirpation of them would be useful to the world, and honorable to those who can effect it."

As intended, Knight's story increased negative feelings towards Native Americans. It was often republished over the next 80 years. This happened especially when there were violent events between white Americans and Natives. American frontiersmen had often killed Native prisoners. But most Americans saw Native culture as wild. Crawford's death greatly strengthened this idea of Natives as "savages." In American memory, the details of Crawford's death became more important than American actions like the Gnadenhütten massacre. The image of the "savage Native" became a common idea. The efforts of peaceful men like Cornstalk and White Eyes were almost forgotten.

|