Cultural depictions of Frederick Barbarossa facts for kids

Frederick I, known as Barbarossa (which means "Redbeard" in Italian), was one of the most famous Holy Roman Emperors. He left a big mark on history, especially in Germany and Italy. Because he was so well-known, people in the 1800s and early 1900s used his image for political reasons. Groups like the Risorgimento in Italy, the German government under Emperor William I, and even the Nazis tried to connect themselves to him.

Today, historians want to look at Frederick I fairly, without using him for political messages. They see him as a powerful ruler who faced many challenges but often found ways to succeed. He made the emperor's role stronger in Germany. However, he also made mistakes when he tried to control the cities in Northern Italy. This led to a long fight. After losing the Battle of Legnano, he changed his approach and found a better way to work with the Italian cities. His smart diplomacy also opened new doors for the empire, especially when his son Henry VI married Constance of Sicily. Recent studies in Germany also look at how Frederick connected with the knightly culture of his time.

Contents

Legends and Stories About Barbarossa

- After he conquered the city of Milan in 1162, Frederick sent the remains of the Three Kings to Cologne. Today, you can still find and honor them in the Cologne Cathedral.

- Frederick died suddenly, which in medieval times was sometimes seen as a punishment from God. To help people understand this, many myths were created. Some stories changed how he died so that he could ask for forgiveness before the end.

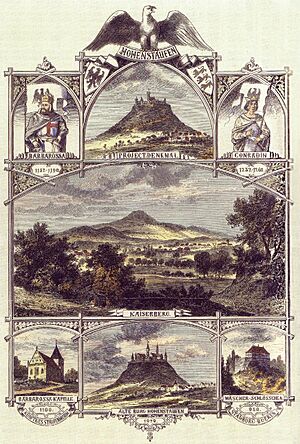

- The most famous legend about Barbarossa is the Kyffhäuser legend. It says he isn't truly dead. Instead, he is sleeping with his knights in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia, Germany. Another version says he sleeps in Mount Untersberg near the border of Bavaria, Germany, and Salzburg, Austria. The legend claims he will wake up and bring back a "Golden Age" to Germany when ravens stop flying around the mountain. His red beard is said to have grown through the table where he sits! Every now and then, he lifts his hand to send a boy out to check if the ravens have stopped flying.

- A similar story was told earlier about his grandson, Frederick II, in Sicily. To gain political support, the German Empire built the Kyffhäuser Monument on top of the Kyffhäuser mountain. This monument suggested that Kaiser Wilhelm I was like a new Frederick. The Prussians didn't care much for the Barbarossa legend at first. It was more popular with princes in Southern Germany. They wanted to show they had a say in the central government, just like in Frederick's time. But after 1871, when Wilhelm I became German emperor, they started promoting the legend actively.

In the Middle Ages, people believed in stories about the "end of the world." These stories often included terrible natural disasters, the arrival of a bad guy called the Antichrist, and then a good king who would fight him. Barbarossa was often seen as this "good king" who would bring peace. Later, German propaganda used these ideas. They presented Frederick Barbarossa and Frederick II as symbols of a "good king." Other leaders like Martin Luther, Frederick the Great, and Bismarck also became part of this idea of a national hero. This idea was later used by the Nazis.

- During the Risorgimento in Italy (a movement for Italian independence), Frederick was seen as a foreign invader. He was the "barbarian" who was defeated by Italian heroes like the Lombard League. This idea influenced how Italian history was written. Stories were told, like one where Frederick supposedly sent Milanese people back with their hands cut off or without eyes. Some schoolbooks in Italy still describe him in a very negative way.

- In Italy, people have mixed feelings about Barbarossa. There are different, even opposite, stories about what he did. In cities like Milan, Tortona, and Asti, which he destroyed, he is still seen as a foreign oppressor. But in cities like Como, Pavia, and Lodi, he is seen more positively. Lodi, for example, complained to Barbarossa about Milan's bullying, which brought him to Italy. These cities see him as an old supporter of their own traditions. In Brienno, he even has a holy image. For Spoleto, good and bad legends are mixed, making him a "beloved enemy."

How Historians See Barbarossa

In 2010, Professor Gianluca Raccagni shared what historians know about Frederick's rule: Frederick is still famous because he worked hard to make the Holy Roman Empire more powerful. He ruled Germany for a long time and kept things stable there. He also had big struggles with the Pope and the Italian cities. He was involved in a crusade and died during it. Frederick almost took away the freedom of the Italian cities. He also nearly brought the Pope under his control and expanded his power in the Mediterranean Sea. His reign also greatly influenced the development of public law.

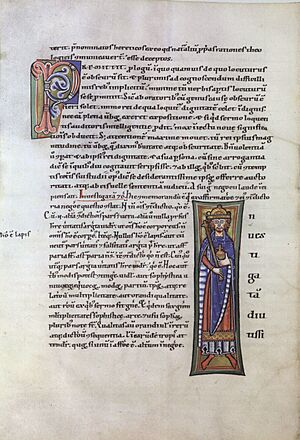

Otto of Freising, Frederick's uncle, wrote a book about his reign called Gesta Friderici I imperatoris (Deeds of the Emperor Frederick). Otto's other main work was a history of the world. But his book about Frederick was much more positive. It showed the great possibilities of the emperor's power. Otto died after writing the first two books, and his assistant, Rahewin, finished the rest.

For a long time, German scholars had to rely on less formal histories to learn about Frederick's reign. Two big attempts were made to write a full biography, but both authors died before finishing. One was by Henry Simonsfeld, who died in 1913. His book ended in 1158. The other important work was by Wilhelm von Giesebrecht, who wrote two volumes about Frederick. Giesebrecht died in 1889, and his student, Bernhard von Simson, completed the work in 1895. This book became the main source for studying Frederick's life. Giesebrecht presented Barbarossa's time as a high point in German history. Some believe this work was meant to make people feel patriotic.

In 1975, Frederick's official documents were published. This, along with people moving away from the Kyffhäuser myth after World War II, led to new biographies. Important recent historians who write in German include Ferdinand Opll, Johannes Laudage, and Knut Görich.

Bernd Schütte says that Ferdinand Opll has greatly improved the study of Frederick I. Opll's book Friedrich Barbarossa shows the emperor as a practical leader who could adapt and recover after defeats.

Knut Görich has written a lot about Frederick. He talks about Frederick's strong belief in "imperial honor." This was linked to how he saw himself as a ruler, his rights, and his duties. Görich doesn't see the 1177 Peace of Venice as a defeat for Frederick. Instead, he sees it as a return to agreement, which helped Frederick later. Historian Graham Loud agrees that the idea of honor was very important during Frederick's reign. Loud also notes that Görich shows Frederick as a man with ambition, good planning skills, and the ability to reward people outside his close group.

Laudage also believed that the idea of honor was key to Frederick's thoughts and actions. He said that in a society without a written constitution, it was important to always show one's reputation and place in society. Frederick showed true knightly behavior and generosity, but also ambition, violence, and ruthlessness. Laudage especially criticized Frederick's use of pure force against Milan, which ultimately failed.

Historians Plassmann and Foerster reviewed a recent English biography of Frederick. They said it was a valuable book for English speakers, even with some unique views. Other biographers also talk about times when the emperor had less power. But they don't see it as happening throughout his whole reign as much as this book does. Plassmann points out that Frederick was widely accepted as king and emperor in Germany. This helped him survive being excommunicated (kicked out of the church), a plague, a big defeat in Italy, and a challenge from a powerful prince. He still ended up as the clear leader of the German army on the Third Crusade.

Wolfgang Stürner's 2019 book about the Hohenstaufen family is highly respected. Stürner believes Frederick was a ruler who tried to bring peace to the Empire. He did this by acting as a judge and creating "peace laws," often successfully. For Stürner, honor was not a big factor in Frederick's major decisions. For example, the main reason for his conflict with Milan was the city's refusal to make peace with other cities. Milan also rejected Frederick's role as a leader chosen by God to keep order.

In Italy, scholars have always paid a lot of attention to Frederick because of his many activities there. Today, the old idea of him as an "oppressor" is not as popular. Researchers now see the conflict as a clash between different political ideas. Both sides tried to find solutions through laws and force.

Knut Görich believes that Italian writers often blame Frederick alone for the destruction of Milan. But the cities allied with him also played a big part. German accounts show that the destruction was seen as revenge, but also as justice. They hoped that once Milan was defeated, more glorious things could be achieved.

Joseph P. Huffman described Frederick I Barbarossa as someone who was "far more successful in diplomatic victories than military ones." He was good at using disagreements among his enemies to his advantage. He was also smart enough to offer his opponents something for their losses while still protecting his own power. He believed in imperial honor but was also realistic about what was possible.

Jenny Benham notes that a treaty in 1177 brought a time of wealth for the Sicilian kingdom. The emperor and his family gained a claim to rule Sicily, and thus most of Italy, which his son Henry and Constance later achieved.

Joseph F. Byrne says that even though the Italian cities' successes were short-lived, their strength against Europe's greatest monarch helped build a strong community spirit that lasted for centuries. Byrne thinks Frederick was flexible, but in Italy, he didn't understand the cities' strong desire for freedom. This stopped him from finding a good solution for 25 years. This, along with his refusal to recognize Pope Alexander III and his need to deal with issues in Germany, prevented him from becoming a direct ruler in Italy.

Peter Wilson believes that the truce in 1177, followed by the Peace of Constance, created a good working relationship between the emperor and the cities. The cities accepted the emperor's rule, and he recognized their freedom. This lasted until a civil war after 1198. Regarding the 1190 Crusade, Wilson writes that Barbarossa died on the way. But even though the expedition didn't take back Jerusalem, it helped the Crusader kingdoms and made crusading more connected to the emperor's role.

Culture During Barbarossa's Time

Frederick Barbarossa's reign was a time when courtly culture and knightly literature became very popular.

Legal Studies

Barbarossa supported learning, especially in law. He was very interested in the Law school of Bologna. He gave special rights to the Bolognese scholars and recognized the important role of law in running the empire. New legal ideas influenced the laws he issued at Roncaglia.

History and Literature

The cultural and intellectual growth at Frederick's court happened because of his expansion into Italy and the Mediterranean. It also grew after his 1156 wedding to Beatrix of Burgundy. The emperor's actions inspired writers and historians to create poems and historical works. Frederick was also interested in the deeds of past rulers. This is seen in Otto of Freising's history of the world and his book about Frederick. Other important works include a poem about Frederick's deeds in Lombardy and an epic poem that turned Otto's prose into verse.

Frederick and his time tried to build a culture of peace in Germany. As the "father of the country," the emperor was expected to bring peace. But Frederick focused on setting a pattern of peace with justice, rather than just affection.

Minnesang

After his marriage to Beatrice, and with the arrival of poets from Burgundy and Provence, the art of minnesang (German love poetry) grew in Barbarossa's court. Early German Minnesingers included Friedrich von Hausen and Bligger II von Steinach.

Architecture

Frederick was a great builder of palaces and public buildings.

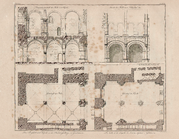

- The Gelnhausen palace was built by Barbarossa to expand his family's lands. The building shows influences from southern France and Lorraine, but all combined into a beautiful and high-quality design.

- The Eger fortress (Czech: Cheb): Around 1180–90, he built the Eger imperial fortress on an old Slavic settlement site. It shows the Hohenstaufen era's love for grand displays. It has a window arcade open to the outside, showing a love of nature. The Black Tower and the double chapel are still standing today.

Barbarossa in Art

Poems

- An unknown poet, likely from the pro-imperial city of Bergamo, wrote The Song of the Deeds of Emperor Frederick in Lombardy.

- The Archpoet, a famous writer of his time, wrote poems about the emperor.

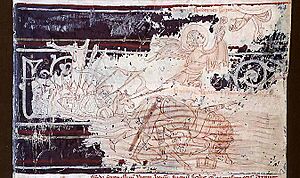

- In a chronicle from 1196, Frederick's death is described like this:

Already he sees the goal of his wishes [the Holy Land]

There he migrates in joy to Christ.

The picture that went with this text showed an angel taking the emperor's soul, like a baby, to God. At the same time, Frederick's body was shown falling into the water, with his crown already sinking. This mixed image of Frederick was later painted over and only uncovered in the 1900s.

- Christian Joseph Matzerath wrote Kaiser Rotbarts Grab (Emperor Redbeard's grave).

Music

The German minnesang tradition started during Frederick's reign. It was inspired by his Crusade and his support for the arts, as well as French troubadour songs. These were mostly love songs, not political ones. Minnesingers like Friedrich von Hausen showed Frederick and his court in their works.

- Der alte Barbarossa, a famous poem about the emperor sleeping in the mountain, was published in 1813 by Friedrich Rückert. It was likely influenced by feelings against Napoleon.

- Gustav Pressel composed a well-known song called Barbarossa about the emperor.

- In 1888–1889, Siegmund von Hausegger composed a large musical work, a symphonic poem called Barbarossa, also inspired by the Kyffhäuser legend.

Plays and Theater

- La battaglia di Legnano: This opera by Giuseppe Verdi was about Frederick's defeat by the Lombard League in 1176.

- Ernst Raupach wrote four plays about Frederick as part of his series on the Hohenstaufen family.

- Christian Dietrich Grabbe wrote the play Kaiser Friedrich Barbarossa in 1829.

- Der Untersberg (The Untersberg) is a musical play from 1829. Its setting is the mountain near Salzburg where the emperor is supposedly asleep.

- Richard Wagner saw a connection between the hero Siegfried and Barbarossa. He thought Barbarossa was like a second coming of Siegfried. Wagner originally planned to write an opera about the emperor.

Visual Arts

- The Wittelsbach family, who became powerful under Frederick, added an eagle to their family symbol in 1166. This eagle represented both the Empire and their region of Bavaria.

- There is a carved stone figure, either of Frederick Barbarossa or his grandson Frederick II, at the Castello di Lagopesole in Italy.

- A drawing from around 1409–1415 shows Emperor Frederick Barbarossa receiving the entreaties of his son for peace.

- A painting called Humiliation of Frederick I Barbarossa by Pope Alexander III was ordered by the Venetian government. It was originally started by Giovanni Bellini and later given to Titian. This painting was destroyed in a fire.

- Tintoretto painted a scene of Barbarossa being crowned by Pope Adrian IV.

- Around 1552–1568, Italian artist Cristofano dell'Altissimo painted a portrait of Frederick Barbarossa.

- In 1596, Haarlem ordered a tapestry showing Emperor Barbarossa and the Patriarch of Jerusalem bestowing Haarlem with an Augmentation of its Arms.

- Sant'Ubaldo e Federico Barbarossa (Saint Ubald of Gubbio and Frederick Barbarossa) is a 1683 painting by Ciro Ferri.

- Frederick's famous portrait in the Kaisersaal in Frankfurt am Main is part of a series of paintings of emperors. This portrait was painted by Karl Friedrich Lessing in 1840. On the ceiling of the Kaisersaal, there are frescoes by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo showing Beatrice of Burgundy being brought to Frederick and their marriage.

- Besides the Kyffhäuser Monument, during the early years of the Second German Empire, an art project linked Frederick with Wilhelm I in Goslar. The old Imperial Palace was decorated with paintings showing Frederick's life. These paintings mixed history with fairytales and legends. In one painting, The proclamation of the Reich, Frederick looks down with approval at the proclamation. Other paintings include Barbarossa awakened and Barbarossa falling on his knees in front of Henry the Lion (showing Frederick begging Henry for military help).

- Frederick Barbarossa expelled from Alexandria is an 1851 painting by Carlo Arienti.

- Friedrich Barbarossa 1157 zu Besançon, den Streit der Parteien schlichtend (showing the emperor trying to separate two fighting groups) is an 1859 painting by Hermann Plüddemann.

- Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld created several images of the emperor, including Death of Barbarossa and The Sleep of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa.

- There was a hall named Barbarossasaal in the Royal Palace of Bavaria in Munich. It had paintings showing Barbarossa's life, such as his election as emperor, his entry into Milan, and his death.

- In 1892, a sculptor named Hans Baur won a competition to build a fountain in Konstanz. This fountain, called Kaiserbrunnen (Imperial Fountain), has figures of four great German emperors: Henry III, Frederick Barbarossa, Maximilian I, and Wilhelm I. Barbarossa's figure is mixed with a large fish, possibly symbolizing his death in water.

- Frederick's statue at the city hall in Nijmegen is part of a group of statues of emperors.

- Madonna di Provenzano con Federico Barbarossa e Alessandro III is a 1959 painting and a 1981 painting showing Frederick kneeling before Pope Alexander III.

- In 1984, a Barbarossa monument was created in Mainz. It shows the emperor with his two sons.

Novels

- He is a character in the fictional work La Religieuse by Marie-Catherine de Villedieu.

- Friedrich's des Ersten letzte Lebenstage is an 1858 novel by Julius Bacher about the emperor's last days.

- Federico Barbarossa all'assedio di Crema romanzo storico is an 1873 novel by Pietro Saraceni.

- Karl Hans Strobl wrote the novel Kaiser Rotbart in 1935.

- Barbarossa is a novel about the emperor by Conrad von Bolanden.

- Kaiser Friedrich Barbarossa: Historischer Roman is a 1954 novel by Heinrich Bauer.

- Frederick is an important character in Wie ein Falke im Sturm.

- Baudolino is a 2011 novel by Umberto Eco. The story is about Baudolino, Frederick's godson.

- Sabine Ebert has written a five-book series about Frederick.

- Adler und Löwe: Friedrich Barbarossa und Heinrich der Löwe im Kampf um die Macht is a 2021 novel about Frederick and Henry the Lion by Paul Barz.

- Le fils chartreux de Barberousse is a 2015 novel by Annie Maas about Terric, Barbarossa's natural son.

- Barbarossa - Im Schatten des Kaisers: Historischer Roman is a 2022 novel by Michael Peinkofer.

Films

- Frederick is played by Amleto Novelli in the 1910 Italian film Federico Barbarossa.

- In the 2009 movie Vision (2009 film), he is played by Devid Striesow.

Barbarossa Cities

Several cities connect themselves to the memory of the emperor. They are called Barbarossasttadt (Barbarossa city). These usually include Sinzig, Kaiserslautern, Gelnhausen, Altenburg, and Bad Frankenhausen. Other cities like Annweiler am Trifels, Bad Wimpfen, Eberbach, and Waiblingen also consider themselves Barbarossa cities.

Events and Festivals

There are many medieval festivals in Germany linked to Frederick and the Hohenstaufen family. Some of the notable ones are:

- The Barbarossa Spectaculum, a big medieval festival held every two years at the Marienberg Fortress in Würzburg.

- The Barbarossa Festspiel in Altenburg.

- The Stauferspektakel in Göppingen.

- The Staufer-Spektakel in Waiblingen.

Since 1981, Como in Italy has organized the Palio del Baradello. In this event, different villages compete to win a special silk banner.

The year 2022 marked the 900th anniversary of Frederick Barbarossa's birth. To celebrate, a stone monument was created in Selm. Events like exhibitions and festivals about Frederick have been planned in various German towns, including a celebration at the Barbarossa Cave.

Recently, a military battalion called "Battalion Barbarossa" created a huge artwork on the ground in Bad Frankenhausen to honor the emperor.

|

See also

- Cultural depictions of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

- Imperial Palace of Goslar

- Wilhelm I, German Emperor

- Barbarossa Palace, Gelnhausen

- Barbarossa city

- Barbarossa Cave

- Kyffhäuser Monument

- Lenzburg Castle

- Kaiserbrunnen in Konstanz (German Wiki)