Deep-sea exploration facts for kids

Deep-sea exploration is like being a detective for the ocean's deepest, darkest secrets! It's all about studying the physical, chemical, and biological conditions in the ocean waters and on the seafloor far beyond the coast. People explore the deep sea for scientific reasons, like learning about new creatures, or for commercial reasons, like finding valuable minerals.

Exploring the deepest parts of the ocean is a fairly new human activity. For a long time, these areas were a mystery. Even today, much of the ocean's depths remain unexplored.

Scientists began exploring the deep sea around the late 1700s or early 1800s. A French scientist named Pierre-Simon Laplace tried to figure out the average depth of the Atlantic Ocean. He did this by watching how tides moved on the coasts of Brazil and Africa. He calculated the depth to be about 3,962 metres (12,999 ft), which was later proven to be very accurate using modern sound-based methods.

Later, as people wanted to lay submarine cables across the ocean, they needed to know the exact depth of the seafloor. This led to the first real investigations of the ocean bottom. The first deep-sea life forms were found in 1864 by Norwegian researchers Michael Sars and Georg Ossian Sars. They discovered a special type of crinoid (a sea creature that looks like a plant) at a depth of 3,109 m (10,200 ft).

A huge step in ocean study happened from 1872 to 1876. British scientists sailed on HMS Challenger, a ship specially changed for exploration. This Challenger expedition traveled over 127,653 kilometres (68,927 nmi). The scientists collected hundreds of samples and measured water conditions. They discovered more than 4,700 new types of marine life, including many deep-sea creatures. They also gave us the first clear picture of major seafloor features, like the deep ocean basins.

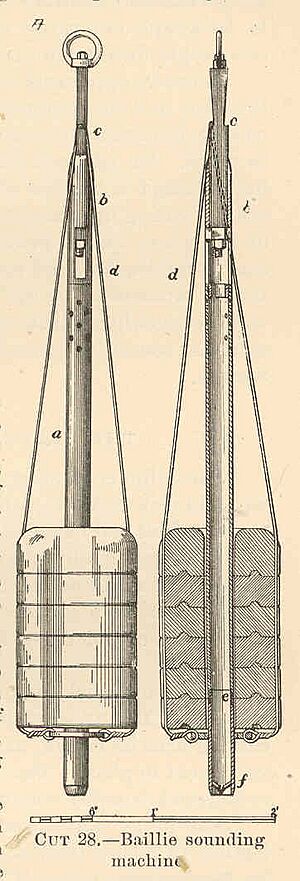

The very first tool used to explore the deep sea was a sounding weight. British explorer Sir James Clark Ross used it in 1840 to reach a depth of 3,700 m (12,139 ft). The Challenger expedition used similar tools called Baillie sounding machines to collect samples from the seafloor.

In the 20th century, deep-sea exploration grew a lot thanks to new inventions. These included sonar systems, which use sound to find objects underwater, and special submarines that could carry people deep down. In 1960, Jacques Piccard and US Navy Lieutenant Donald Walsh went down in their bathyscaphe Trieste to the deepest known part of the ocean, the Mariana Trench. Then, in 2012, filmmaker James Cameron also went to the Mariana Trench in his Deepsea Challenger, filming and collecting samples from the very bottom for the first time.

Even with all these advancements, going to the ocean bottom is still very difficult. Scientists are now trying to find ways to study this extreme environment from their ships. They hope to use advanced fiber optics, satellites, and remote-control robots to explore the deep sea from a computer screen on deck, instead of looking out a small window.

Contents

Amazing Discoveries and Milestones

Exploring the deep sea is tough because of the extreme conditions, like huge pressure and freezing cold. That's why its history of exploration is quite short. Here are some important moments in deep-sea exploration:

- 1521: Ferdinand Magellan tried to measure the depth of the Pacific Ocean with a weighted line but couldn't find the bottom.

- 1818: British researcher Sir John Ross found that deep seas have life. He caught jellyfish and worms at about 2,000 m (6,562 ft) depth.

- 1843: Edward Forbes thought there was little life in the deep sea and none deeper than 550 m (1,804 ft). This was called the Abyssus theory.

- 1850: Near Lofoten, Michael Sars found many different deep-sea animals at 800 m (2,625 ft), proving the Abyssus Theory wrong.

- 1872–1876: The Challenger expedition on HMS Challenger was the first big study of the deep sea. It showed that the deep sea has many unique living things.

- 1930: William Beebe and Otis Barton were the first humans to reach the deep sea in their Bathysphere. They went down 435 m (1,427 ft) and saw jellyfish and shrimp.

- 1960: Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh reached the very bottom of the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. They went 10,740 m (35,236 ft) deep in their vessel Trieste and saw fish!

- 2012: The vessel Deepsea Challenger, piloted by James Cameron, made the second crewed trip and first solo trip to the bottom of the Challenger Deep.

- 2020: Dr. Kathryn Sullivan and Vanessa O'Brien became the first women to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep at 10,925 m (35,843 ft) in the vessel Limiting Factor.

Tools for Ocean Exploration

Early tools for deep-sea exploration were simple. The sounding weight was a tube with a heavy base. When it hit the seafloor, it would collect a sample of the mud. Sir James Clark Ross used this tool in 1840. The Challenger expedition used improved versions called "Baillie sounding machines." They also used dredges and scoops on ropes to collect samples of mud and creatures from the seabed.

A more advanced tool is the gravity corer. This tool helps scientists collect long samples of sediment (mud and sand) from the ocean floor. It's a heavy, open-ended tube that drops into the seabed, collecting a sample up to 10 m (33 ft) long. These samples show layers of sediment, which can tell scientists about past climates, like during ice ages. Even deeper samples can be taken with drills on special ships like the JOIDES Resolution, which can drill 1,500 m (4,921 ft) below the ocean bottom.

Echo-sounding instruments are also widely used. These tools use sound waves to measure the depth of the water. A sound pulse is sent from the ship, bounces off the seafloor, and returns to the ship. By measuring the time it takes, scientists can figure out the depth. This method has helped map most of the ocean floor.

Other useful tools include high-resolution video cameras, thermometers, pressure meters, and seismographs (for measuring earthquakes). These are either lowered by cables or attached to special underwater buoys. Scientists can also track deep-sea currents using floats with ultrasonic sound devices. Research vessels use precise navigation systems, like satellite navigation, to stay in a fixed position. Magnetometers are used to find metal objects, like shipwrecks, by detecting magnetic materials.

Amazing Deep-Sea Vehicles

Because of the extreme pressure, divers can only go so deep without special equipment. The deepest a freediver has gone is about 253 m (830 ft). For scuba divers, the record is around 318 m (1,043 ft).

Special Atmospheric diving suits protect divers from pressure, allowing them to reach about 600 m (1,969 ft). Some even have small propellers to help the diver move.

To go even deeper, explorers need special pressure-resistant vehicles or robots. The first practical deep-diving vehicle was the Bathysphere, designed by American explorer William Beebe and engineer Otis Barton. In 1930, they reached 435 m (1,427 ft), and in 1934, they went down to 923 m (3,028 ft). Beebe would look out a small window and describe what he saw to Barton on the surface by telephone.

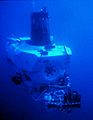

In 1948, Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard invented the bathyscaphe. This was a deep-sea vessel with a gasoline-filled float and a strong steel cabin. In 1954, Piccard reached 4,000 m (13,123 ft) in his bathyscaphe. His son, Jacques Piccard, helped build an improved bathyscaphe called Trieste. In 1960, Jacques Piccard and US Navy Lieutenant Donald Walsh made history by diving to the deepest known point on Earth, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, reaching 10,915 m (35,810 ft).

Today, many crewed submersibles are used worldwide. For example, the American-built DSV Alvin, operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, can carry three people and dive to about 3,600 m (11,811 ft). Alvin has lights, cameras, computers, and robotic arms to collect samples. It has made over 3,000 dives and helped discover amazing creatures like giant tube worms near the Galápagos Islands.

Robots of the Deep

One of the first unmanned deep-sea vehicles was the benthograph in the 1950s. It was a heavy steel sphere with a camera and light, used to take photos miles under the sea.

Remote operated vehicles (ROVs) are robots controlled by a cable from a surface ship. They can reach depths of up to 6,000 m (19,685 ft). Newer robots called AUVs, or autonomous underwater vehicles, are programmed in advance and can explore on their own without a cable. Hybrid ROVs (HROVs) combine features of both. For example, Argo was used in 1985 to find the wreck of the RMS Titanic, and a smaller robot, Jason, explored the shipwreck.

Building Deep-Sea Vehicles

Deep-sea vehicles must be built to handle extreme pressure and freezing temperatures. Their shape, materials, and how they are built are all very important. The part that holds people must be hollow and keep the pressure inside safe for humans. Unmanned vehicles also need to protect their sensitive electronics from the outside pressure.

These vehicles are usually built in strong shapes like spheres, cones, or cylinders, because these shapes spread out the pressure best. Common metals used are aluminum, steel, and titanium. Aluminum is good for medium depths. Steel is very strong but heavy. Titanium is almost as strong as steel but much lighter. However, titanium is more expensive and harder to work with. For example, the Deepsea Challenger used a steel sphere for its pilot, which could withstand pressure far deeper than the Mariana Trench. Smaller titanium spheres were used for the electronics.

What We've Learned

Deep-sea exploration has led to many important scientific discoveries:

- In 1974, submersibles like Alvin explored the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. They found young solidified magma on both sides of a crack, which helped prove that the seafloor is slowly spreading apart (this is part of plate tectonics).

- Between 1979 and 1980, scientists found amazing "hot springs" called hydrothermal vents in the Galápagos rift. These vents shoot out hot water (up to 300 °C, 572 °F) and dissolved metals, forming dark, smoke-like plumes. These hot springs are important for creating deposits rich in metals like copper and nickel.

- Scientists have collected many biological samples, finding new species and learning about how life thrives in the deep sea. For instance, studies have shown that marine bacteria and viruses play a big role in the deep ocean's productivity.

Deep-Sea Mining

Deep-sea exploration is also gaining interest because of the rich mineral resources found on the ocean floor. These were first discovered by the Challenger expedition in 1873. Many countries and private companies are now exploring areas like the Clarion–Clipperton fracture zone in the Pacific Ocean. This exploration is not only finding new minerals but also discovering new marine species and tiny microbes that could be useful for modern medicine.

See also

- Census of Marine Life

- NEPTUNE

- Ocean Drilling Program

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |