Draža Mihailović facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Draža Mihailović

|

|

|---|---|

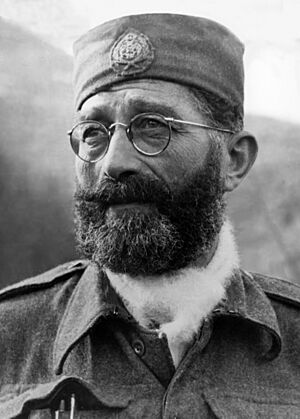

Mihailović in 1943

|

|

| Birth name | Dragoljub Mihailović |

| Nickname(s) | Čiča Draža (Uncle Draža) |

| Born | 27 April 1893 Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia |

| Died | 17 July 1946 (aged 53) Belgrade, PR Serbia, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1910–1945 |

| Rank | Army general |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Relations | Mihailo Mihailović (Father), Smiljana Mihailović (née Petrović) (Mother) |

| Signature | |

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović (born April 27, 1893 – died July 17, 1946) was a Serbian general from Yugoslavia during World War II. He led a group called the Chetniks. They were a royalist (meaning they supported the king) and nationalist (meaning they strongly supported their own nation) guerrilla force. They started fighting after Germany invaded Yugoslavia in 1941.

Mihailović was born in Ivanjica and grew up in Belgrade. He fought bravely in the Balkan Wars and World War I. After Yugoslavia fell in April 1941, Mihailović formed the Chetniks at Ravna Gora. He began fighting against the German forces. At first, he worked with Josip Broz Tito's Partisans.

However, their different ideas and distrust caused them to split up. By late 1941, they were fighting each other. Many Chetnik groups worked with the Axis powers (Germany and Italy). This, along with the British being unhappy with Mihailović's lack of action, led the Allies to support Tito instead in 1944. Mihailović also worked with other leaders who supported the Axis at the end of the war.

After the war, Mihailović went into hiding but was caught in March 1946. He was put on trial by the new communist government of Yugoslavia. He was found guilty of serious crimes against the state and war crimes. He was executed in Belgrade in July 1946. What he was responsible for, including working with the enemy and violence against ethnic groups, is still debated. In May 2015, a court in Serbia overturned his conviction. They said his trial was unfair and based on politics.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was born on April 27, 1893, in Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia. His parents were Mihailo and Smiljana Mihailović. His father worked as a court clerk. Draža became an orphan at age seven and was raised by his uncle in Belgrade.

Since both of his uncles were military officers, Mihailović decided to join the Serbian Military Academy in October 1910. He fought as a cadet (a military trainee) in the Serbian Army during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). He was given the Silver Medal of Valor for his bravery. He became a second lieutenant as one of the best students in his class.

He also served in World War I and was part of the Serbian Army's difficult retreat through Albania in 1915. He received several awards for his actions on the Salonika front. After the war, he joined the Royal Guard of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

In 1921, he went to the Superior Military Academy of Belgrade. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1930. He also spent three months in Paris, France, studying at a military school. In 1935, he became a military representative in Bulgaria and then in Czechoslovakia. He was promoted to the rank of colonel on September 6, 1935.

His military career almost ended in 1939. He wrote a report that strongly criticized the way the Royal Yugoslav Army was set up. He suggested focusing forces in the mountains and using mobile Chetnik units. The Minister of the Army was very angry and ordered him to be punished. However, the minister retired, and Mihailović avoided these punishments.

When Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers, Colonel Mihailović was working in northern Bosnia. He briefly led a "Rapid Unit" before the Yugoslav High Command surrendered on April 17, 1941.

World War II

After Germany, Italy, and Hungary invaded and took over Yugoslavia, Mihailović and a small group of soldiers escaped. They hoped to find other Yugoslav army units still fighting in the mountains. On April 29, Mihailović and about 80 men crossed into German-occupied Serbia. Mihailović wanted to create a secret intelligence group and contact the Allies. It's not clear if he planned to start a full armed resistance at first.

Forming the Chetniks

Mihailović set up a small group of officers with armed guards. He called it the "Command of Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army." When he arrived at Ravna Gora in early May 1941, he realized his group was almost alone. He started making lists of people who could join. Civilians, mostly smart people from the Serbian Cultural Club, also joined to help with propaganda.

Other Chetnik groups, like those led by Kosta Pećanac, did not want to resist the invaders. To show they were different, Mihailović's followers called themselves the "Ravna Gora movement." Their main goal was to free the country from the German, Italian, and Ustaše armies. They also wanted to free the Independent State of Croatia.

Mihailović spent most of 1941 bringing together scattered Yugoslav army soldiers and finding new recruits. In August, he created a group of Serb political leaders to advise him. On September 13, 1941, Mihailović sent his first radio message to King Peter's government-in-exile. He announced that he was organizing soldiers to fight the Axis powers.

Mihailović's plan was to avoid direct battles with the Axis forces. He wanted to wait until Allied forces arrived in Yugoslavia before starting a big uprising. His Chetniks had some small fights with the Germans. But the Germans would punish civilians severely (reprisals), which made the Chetniks careful.

Meanwhile, after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) also began to fight. Led by Josip Broz Tito, they called for a popular uprising in July 1941. Tito then formed a communist resistance group called the Yugoslav Partisans. By late August, both Chetniks and Partisans were attacking Axis forces, sometimes together.

On October 28, 1941, Mihailović received an order from the Yugoslav government-in-exile. It told him to avoid early actions that could lead to German reprisals. Mihailović did not want to do sabotage that could easily be traced back to the Chetniks. His hesitation meant that the Partisans did most of the early sabotage. Mihailović lost some commanders and followers who wanted to fight the Germans to the Partisan movement.

Even though Mihailović asked for quiet support, British and Yugoslav government propaganda quickly praised him. The idea of a resistance movement in occupied Europe boosted morale. On November 15, the BBC announced that Mihailović was the commander of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland. This became the official name of Mihailović's Chetniks.

Conflicts with Axis Troops and Partisans

Mihailović soon realized his men could not protect Serbian civilians from German reprisals. The Chetniks were also worried that the Partisans might take over Yugoslavia after the war. They did not want to fight in ways that would make Serbs a minority later. Mihailović's plan was to unite Serb groups and build an organization strong enough to take power after the Axis left.

In contrast, the Partisans wanted open resistance. This appealed to Chetniks who wanted to fight the occupation. By September 1941, Mihailović started losing men to the Partisans.

On September 19, 1941, Tito met with Mihailović to discuss an alliance. But they could not agree because their goals were too different. Tito wanted a full attack, while Mihailović thought a general uprising was too risky. Tito believed Mihailović was playing a "double game" by talking to German forces. Mihailović was indeed in contact with the Nedić government, receiving money. Mihailović also wanted to stop Tito from leading the resistance. Tito's goals were against Mihailović's goals of bringing back the king and creating a larger Serbia.

At the end of September, the Germans launched a big attack against both Partisans and Chetniks. On November 1, the Chetniks attacked the Partisan headquarters at Užice, but they were pushed back. On the same day, Mihailović's troops captured two groups of Partisans. Between November 6 and 9, at least 41 of them were executed near Chetnik headquarters. Mihailović was present during these executions.

On November 11, Mihailović met with a German official. Mihailović told the Germans that he did not intend to fight them. He claimed he never truly agreed with the communists, saying they were led by foreigners. It seems Mihailović offered to stop activities in towns and along main roads. But no agreement was reached because the Germans wanted the Chetniks to surrender completely. After the talks, the Germans tried to arrest Mihailović. Mihailović kept these talks secret from the Yugoslav government-in-exile and the British. On November 13, Mihailović's Chetniks handed over 365 Partisan prisoners to the Germans. The German army later executed at least 261 of these Partisans.

Mihailović's attack on the Partisan headquarters failed. The Partisans quickly counterattacked. Within two weeks, the Partisans pushed back the Chetniks and surrounded Mihailović's headquarters. Mihailović was in a difficult situation.

In mid-November, the Germans launched an attack against the Partisans. Tito offered to negotiate with Mihailović, leading to a ceasefire on November 20 or 21. On November 28, Tito and Mihailović had their last phone call. Mihailović said he would spread out his forces. On November 30, Mihailović's unit leaders decided to join the "legalized" Chetniks under General Nedić's command. This allowed them to fight the Partisans without being attacked by the Germans. About 2,000–3,000 of Mihailović's men joined the Nedić regime. This gave them salaries and an alibi (an excuse) from the collaborationist government. Mihailović also thought he could secretly influence the Nedić administration.

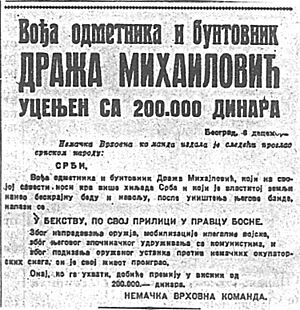

On December 3, the Germans ordered an attack on Mihailović's forces. On December 5, Mihailović was warned about the attack. He turned off his radio and scattered his command and remaining forces. He narrowly escaped capture. On December 10, the Germans put a reward on his head. Meanwhile, on December 7, the BBC announced his promotion to brigade general.

Activities in Montenegro and Serbia

Mihailović did not use his radio to contact the Allies again until January 1942. In early 1942, the Yugoslav government-in-exile made strengthening Mihailović's position a main goal. On January 11, Mihailović was named "Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Forces" by the government-in-exile. The British had stopped supporting him in late 1941 because of reports of fighting between Chetniks and Partisans.

In April 1942, Mihailović, still hiding in Serbia, reconnected with the British. In May, the British started sending some aid to the Chetniks again. Mihailović then went to Montenegro, arriving on June 1. He set up his headquarters there and was formally appointed as Chief-of-Staff of the Supreme Command of the Yugoslav Army. A week later, he was promoted to General of the Army.

In Montenegro, Mihailović found a complicated situation. Local Chetnik leaders were working with the Italians against the Partisans. Mihailović later said he didn't know about these deals before he arrived. He had to accept them because these leaders only followed his orders if it suited their interests. Mihailović tried to make the best of it. He approved destroying communist forces. He also hoped to use the Chetniks' connections with the Italians to get food, weapons, and ammunition. He expected an Allied landing in the Balkans.

In December, a Chetnik "youth conference" was held. It expressed strong nationalist views. It made claims on parts of Albania, Bulgaria, Romania, and Italy. It also suggested bringing back the king with a temporary Chetnik dictatorship. Mihailović did not attend but sent representatives. In the same month, Mihailović told his officers that Partisan units were full of "thugs" from various groups, including Ustašas, Jews, Croats, and others.

In the Independent State of Croatia, Chetnik leaders worked with the Italians. The Italians used these Chetniks as local anti-communist forces. Chetniks from Montenegro came to help Bosnian Serbs against the Ustaše. They committed violence in Foča until the Italians stepped in. The Chetniks also asked the Italians for protection from Ustaše revenge.

In the autumn of 1942, Mihailović's Chetniks sabotaged several railway lines. These lines were used to supply Axis forces in North Africa. In September and December, Mihailović's actions seriously damaged the railways. The Allies gave him credit for helping their efforts in Africa. However, some British reports later questioned if Mihailović truly deserved all the credit for these sabotages.

In early September 1942, Mihailović called for people to disobey the Nedić government. This led to fighting between Chetniks and Nedić's followers. The Germans, who Nedić had asked for help, responded with mass terror. They attacked the Chetniks in late 1942 and early 1943. Thousands of people were arrested. It's estimated that 1,600 Chetnik fighters were killed by Germans in December 1942. These actions stopped much of Mihailović's anti-German activity. Adolf Hitler wrote to Benito Mussolini in February 1943, saying that Mihailović's supporters were a "special danger."

Mihailović had trouble controlling his local commanders. They often didn't have radios and used messengers. He was aware that many Chetnik groups were committing crimes against civilians and trying to remove non-Serb groups from certain areas. Many acts of terror were committed by Chetnik groups against their enemies. This was worst between October 1942 and February 1943.

Allied Support Changes

By late 1942, the British were concerned about Mihailović's lack of action. They sent a senior officer, Colonel S. W. Bailey, to Mihailović in Montenegro. His job was to gather information and see if Mihailović was sabotaging railroads. For months, the British tried to get Mihailović to stop working with Axis forces and fight the occupiers, but they were not successful.

In January 1943, British intelligence reported that Mihailović's commanders had made deals with Italian authorities. They concluded that while aid to Mihailović was still needed, it might be good to help other resistance groups and try to unite the Chetniks and Partisans. British officers reported that Mihailović had not been in touch with the Germans. But his forces had sometimes helped the Italians against the Partisans.

On February 28, 1943, Mihailović gave a speech to his troops. A British officer, Bailey, reported that Mihailović complained about the British. He said they expected Serbs to fight without giving them enough help. He also said he would keep taking help from the Italians if it helped him destroy the Partisans. According to Bailey, he added that his enemies were the Ustaše, Partisans, Croats, and Muslims. He would only fight Germans and Italians after dealing with them.

This report had a very bad effect on the British. It marked the beginning of the end for British-Chetnik cooperation. The British officially complained to the Yugoslav government-in-exile. They demanded explanations about Mihailović's actions and his cooperation with the Italians. The British then announced they would send him more supplies. Also, in early 1943, the BBC started broadcasting more favorably about the Partisans. They described them as the only resistance movement in Yugoslavia.

Defeat in the Battle of the Neretva

During a major Axis operation called Case White, the Italians strongly supported the Chetniks. They hoped the Chetniks would defeat the Partisans. The Germans did not like this cooperation. Mihailović himself joined his troops in Herzegovina near the Neretva River to try and fix the situation. But the Partisans defeated the Chetnik troops and crossed the Neretva. In March, the Partisans made a truce with Axis forces to gain time to defeat the Chetniks. This brief truce helped Tito's forces strike a severe blow to Mihailović's troops.

In May, the Germans attacked the Montenegrin Chetniks. Mihailović escaped. By late May, the Italians also turned against the Chetniks. They offered a reward for Mihailović's capture.

Allied Support Shifts

In April and May 1943, the British sent more missions to both the Partisans and the Chetniks. During the summer, the British sent supplies to both groups. Mihailović returned to Serbia, and his movement quickly became strong again in the region. He received more weapons from the British. He carried out some sabotage actions and fought with Bulgarian troops. But he generally avoided the Germans, thinking his troops were not strong enough yet.

In Serbia, Mihailović's organization controlled the mountains where Axis forces were absent. The Nedić government was largely influenced by Mihailović's men. Many of their soldiers secretly supported him. After his defeat, Mihailović tried to improve his organization. He also tried to connect with Croats and other political groups. The United States sent officers to join the British mission with Mihailović. The Germans became worried about the Partisans' growing strength. They made local agreements with some Chetnik groups, but not with Mihailović himself.

From early 1943, the British became more impatient with Mihailović. They learned from German messages that the Chetniks' cooperation with the Italians was too much. They also saw that the Partisans were doing the most damage to the Axis.

When Italy left the war in September 1943, the Chetniks in Montenegro were attacked by both Germans and Partisans. Several Chetnik leaders openly worked with the Germans against the stronger Partisans. In October 1943, Mihailović agreed to do two sabotage operations at the Allies' request. This made him even more wanted by the Germans.

By November and December 1943, the Germans realized Tito was their most dangerous enemy. German officials made secret agreements with four of Mihailović's commanders to stop fighting for a few weeks. These truces were kept secret but the British found out through intercepted messages. There is no proof Mihailović was directly involved or approved, but British intelligence thought he might have known. In late October, messages showed that Mihailović had ordered all Chetnik units to work with Germany against the Partisans.

The British were increasingly worried that the Chetniks preferred fighting Partisans over Axis troops. At a conference in Moscow in October 1943, British leaders expressed their frustration with Mihailović's lack of action. A report from a British officer with the Partisans convinced Churchill that Tito's forces were the most reliable resistance group. At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Churchill argued for supporting the Partisans.

On December 10, Churchill told King Peter II that he had clear proof of Mihailović working with the enemy. He said Mihailović should be removed from the Yugoslav cabinet. In early December, Mihailović was asked to do an important sabotage mission against railways. This was seen as a "final chance" for him to prove himself. But he failed to give the order. On January 12, 1944, British intelligence reported that Mihailović's commanders had worked with Germans and Italians. They said Mihailović himself had allowed and sometimes approved their actions. This sped up the British decision to remove their officers from Mihailović. The mission left in the spring of 1944.

After May and the British mission left, Mihailović kept sending radio messages to the Allies and his government. But he no longer received replies.

Operation Halyard

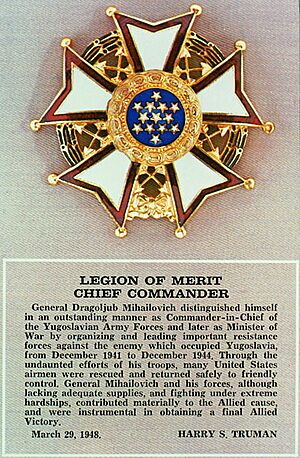

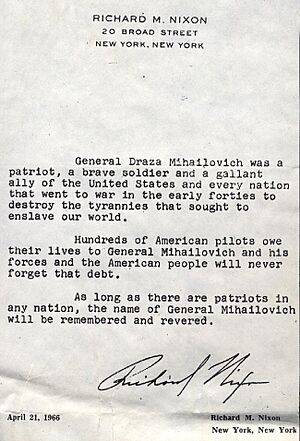

In July and August 1944, Mihailović ordered his forces to help the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS). They successfully rescued hundreds of downed Allied airmen between August and December 1944. This was called Operation Halyard. For this, he was later given the Legion of Merit award by U.S. President Harry S. Truman.

However, Mihailović's Chetniks also rescued German airmen and handed them over to the German forces. The Americans had less information about the war in Yugoslavia than the British. So, they were less happy about the British leaving Mihailović. They were also more careful about supporting the Partisans. Some Yugoslavs were also evacuated in Operation Halyard. They tried to get more support for Mihailović's movement abroad, but it was too late to change Allied policy.

Government in Exile

In July, a new Yugoslav government-in-exile was formed. Mihailović was not included as a minister. However, he remained the official chief-of-staff of the Yugoslav Army. On August 29, King Peter officially ended Mihailović's position. On September 12, King Peter broadcast a message from London. He told all Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to "join the National Liberation Army under the leadership of Marshal Tito." He also said he strongly condemned anyone using the King's name to justify working with the enemy. Although the King did not name Mihailović, it was clear who he meant. This message greatly hurt the Chetniks' morale. Many men left Mihailović after the broadcast. Others stayed loyal to him.

Mihailović felt abandoned by his former allies. In August 1944, he said he had fought for democracy against dictatorship. He felt bitter that he was deserted by those who believed in democracy. But he was satisfied that he had fought bravely and honestly.

Defeat in 1944–45

In late August 1944, the Soviet Union's Red Army reached Yugoslavia's eastern borders. In early September, they invaded Bulgaria and forced it to turn against the Axis. Mihailović's Chetniks were not well-armed enough to stop the Partisans in Serbia. Some of Mihailović's officers met with German officers on August 11. They wanted to arrange a meeting for Mihailović to discuss more cooperation.

As the Red Army got closer, Mihailović thought the war's outcome would depend on Turkey joining the fight. He also hoped for an Allied invasion in the Balkans. He told all Yugoslavs to stay loyal to the King. He claimed the King had sent him a message saying not to believe reports about his dismissal. His troops began to break up outside Serbia in mid-August. He tried to reach out to Muslim and Croat leaders for a national uprising. But he had little success with non-Serbs.

Mihailović ordered a general mobilization on September 1. His troops fought against the Germans and Bulgarians, while also being attacked by the Partisans. On September 4, Mihailović ordered his commanders not to take any action without his orders, except against the communists. German sources confirm Mihailović's loyalty to them during this time. The Partisans then entered Chetnik territory. They fought a difficult battle and defeated Mihailović's main force by October. On September 6, what was left of Nedić's troops openly joined Mihailović.

The Red Army met both Partisans and Chetniks as they entered from Romania and Bulgaria. They briefly worked with the Chetniks against retreating Germans, then disarmed them. Mihailović sent a group to the Soviet command, but his representatives were ignored and arrested. Mihailović's movement in Serbia fell apart under attacks from Soviets, Partisans, Bulgarians, and fighting with retreating Germans. Still hoping for an Allied landing, he headed for Bosnia with his staff and a few hundred men.

In January 1945, Mihailović tried to gather his forces again. But his troops were greatly reduced and tired. Some sold their weapons or stole from local people. On April 13, Mihailović set out for northern Bosnia. He planned a long march back to Serbia to start a new resistance movement, this time against the communists. His units were greatly reduced by clashes with the Ustaše and Partisans, as well as disagreements and disease. On May 10, they were attacked and defeated by the Yugoslav People's Army, the reorganized Partisan force. Mihailović managed to escape with 1,000–2,000 men, who slowly scattered. Mihailović himself went into hiding in the mountains with a small group of men.

Capture, Trial, and Execution

The Yugoslav authorities wanted to catch Mihailović alive to put him on a big trial. He was finally caught on March 13, 1946. The details of how he was caught were kept secret for sixteen years. One story says that men pretending to be British agents offered him help and an escape by plane. After thinking about it, he got on the plane, only to find it was a trap set by the secret police. Another story, from the Yugoslav government, says he was betrayed by Nikola Kalabić, who revealed his hiding place for a lighter punishment.

The trial of Draža Mihailović began on June 10, 1946. Other important Chetnik figures were also on trial. The main prosecutor was Miloš Minić. The Allied airmen Mihailović had rescued in 1944 were not allowed to speak in his favor. Mihailović avoided some questions by blaming his officers for not following his orders. The trial showed that he never had full control over his local commanders. A group was set up in the United States to try and get a fair trial for Mihailović, but it didn't help. Mihailović is quoted as saying in his final statement, "I wanted much; I began much; but the gale of the world carried away me and my work."

Historians say the trial was not fair. They believe Mihailović was not guilty of all the charges against him. Mihailović was found guilty of serious crimes against the state and war crimes. He was executed on July 17, 1946. He was executed with nine other officers. His body was reportedly covered with lime, and the location of his unmarked grave was kept secret.

Rehabilitation

In March 2012, Mihailović's grandson, Vojislav Mihailović, asked for his grandfather to be officially cleared of the charges. This announcement caused negative reactions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia.

The High Court officially cleared Draža Mihailović on May 14, 2015. This decision reversed the 1946 judgment that sentenced him to death for working with the Nazi forces and took away his citizen rights. The court ruled that the communist government's trial was based on politics and ideas, not fairness.

Family

In 1920, Mihailović married Jelica Branković. They had three children. One of his sons, Branko Mihailović, supported the communists and later the Partisans. His daughter, Gordana Mihailović, also sided with the Partisans. She spent most of the war in Belgrade. After the Partisans took the city, she spoke on the radio to say her father was a traitor. While Mihailović was in prison, his children did not visit him. Only his wife visited him. In 2005, Gordana Mihailović personally accepted her father's award in the United States. Another son, Vojislav Mihailović, fought with his father and was killed in battle in May 1945. His grandson, Vojislav Mihailović (born 1951), is a Serbian politician.

Legacy

Historians have different opinions about Mihailović. Some say a main reason for his defeat was that he didn't grow professionally or politically. This made him unable to handle the difficult war and the complex situation of the Chetniks. They also criticize him for losing Allied support because the Chetniks worked with the Axis. They also point to his idea of "passive resistance," which seemed like doing nothing.

Almost sixty years after his death, on March 29, 2005, Mihailović's daughter, Gordana, received a posthumous award from U.S. President George W. Bush. This decision was controversial. In Croatia, some protested, saying Mihailović was directly responsible for war crimes committed by the Chetniks.

With the breakup of Yugoslavia and the rise of ethnic nationalism, how people see Mihailović's actions has changed. Some in Serbia and other Serb-populated areas now challenge the idea that he worked with the enemy.

Monuments to Draža Mihailović exist in several places, including Ravna Gora (1992), Ivanjica, Lapovo, and in North America. In Republika Srpska, many streets and squares are named after him. As of 2019, a street in Kragujevac is named after him. Memorial plaques on Ravna Gora say, "We'll never forget Čiča Draža - your children, your young Chetniks of Serbia."

Images for kids

-

Draža Mihailović as a small pet in the hands of the supposedly Jewish-controlled United States, United Kingdom and Soviet Union as part of Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory, depicted in a poster from the Grand Anti-Masonic Exhibition.

-

"Instrukcije" ("Instructions") of 1941 attributed to Mihailović ordering the cleansing of non-Serbs from territories claimed by the Chetniks as part of a Greater Serbia.

See also

In Spanish: Draža Mihajlović para niños

In Spanish: Draža Mihajlović para niños

- Operation Halyard

- George Musulin

- Operation Hydra (Yugoslavia)

- Yugoslavia and the Allies

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |