Breakup of Yugoslavia facts for kids

| Part of the Cold War, the Revolutions of 1989 and the Yugoslav Wars |

|

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1943–92)

Slovenia (25 June 1991–) Croatia (25 June 1991–) Republic of Serbian Krajina (1991–95; became a part of Croatia after Operation Storm) Republic of North Macedonia (1991–; named "Republic of Macedonia" until 2019) Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–95; became a part of Bosnia and Herzegovina) Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia (1991–94; became a part of Bosnia and Herzegovina) Republika Srpska (1992–95; became part of Bosnia and Herzegovina) Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992–2003; reconstructed into the "State Union of Serbia and Montenegro" in 2003–06) Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia (1991–94; became a part of Bosnia and Herzegovina) Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995–) UN Transitional Administration in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia (1996–1998; became a part of Croatia) Montenegro (3 June 2006–) Serbia (5 June 2006–) Kosovo (17 February 2008–; only partially recognised, claimed by Serbia) |

|

| Date | 25 June 1991 – 27 April 1992 (10 months and 2 days) |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Outcome |

|

Yugoslavia was a country in Europe that broke apart in the early 1990s. This happened after a time of big political and economic problems in the 1980s. When the country split, it led to a series of conflicts called the Yugoslav Wars. These wars mostly affected Bosnia and Herzegovina, parts of Croatia, and later, Kosovo.

After World War II, Yugoslavia was set up as a federation, which means it was a group of six republics working together. These republics had borders based on different ethnic groups and history. They were: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Serbia also had two special areas called Vojvodina and Kosovo.

Each republic had its own leaders, and problems were usually solved at the federal (country-wide) level. Yugoslavia was quite successful for a while, with good economic growth and stability, especially under its leader, Josip Broz Tito. But after Tito died in 1980, the government struggled to handle new economic and political problems.

In the 1980s, people in Kosovo started asking for their area to become a full republic. This led to tensions between Albanians and Serbs there. Many Serbs felt that the special powers given to these areas were hurting their interests. In 1987, Slobodan Milošević became a powerful leader in Serbia. He gained support by promising to protect Serbs and by taking more control over Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Montenegro.

Leaders in Slovenia and Croatia didn't like Milošević's centralizing ideas. They wanted more democracy and freedom for their republics, similar to what was happening in other parts of Eastern Europe in 1989. The main communist party of Yugoslavia broke up in January 1990.

During 1990, most republics held their first multi-party elections. In most places, new nationalist parties won, except in Montenegro and Serbia, where Milošević and his allies stayed in power. People started talking more and more about their own national groups. Between June 1991 and April 1992, four republics declared independence. Only Montenegro and Serbia remained together.

Germany was one of the first countries to recognize Slovenia and Croatia as independent. But the situation for ethnic Serbs living outside Serbia and Montenegro, and for ethnic Croats outside Croatia, became very difficult. After some conflicts, the Yugoslav Wars began, first in Croatia and then, very seriously, in Bosnia and Herzegovina. These wars caused a lot of damage that is still felt today. On April 27, 1992, Serbia and Montenegro formed a new country called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which officially marked the end of the old Yugoslavia.

Contents

Why Yugoslavia Broke Apart

Yugoslavia was located in the Balkans, a region with a long history of different ethnic groups living together. Several things led to its breakup.

Before World War II, there were already tensions because Serbs were a large group in the country. Croats and Slovenes wanted more freedom for their regions, while Serbs saw the new country as an extension of Serbia. These differences often led to conflicts.

During World War II, the occupying forces used these tensions. They set up a Croat-led government that treated Serbs very badly. In response, some Serb groups also committed violence against non-Serbs. These terrible events from the war left deep scars and mistrust between different groups.

After the war, Yugoslavia became a strong industrial country with a good economy. People had free healthcare, high literacy rates, and long lives. Its army was also very strong. Yugoslavia was unique because it wasn't fully aligned with either the West or the Soviet Union during the Cold War. This allowed it to get loans from both sides.

However, the central government started to lose control. The 1974 constitution gave more power to the republics and autonomous regions. This was meant to give different groups more say, but it also created new problems.

- Economic Problems: Yugoslavia borrowed a lot of money in the 1970s, which became hard to repay in the 1980s. This led to high inflation and a recession. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) demanded strict economic changes, which meant cutting subsidies and causing more hardship for ordinary people. This made people angry at the leaders and led to many strikes.

- Differences in Wealth: The richer republics like Slovenia and Croatia felt they were paying too much to support the poorer regions. The poorer regions, like Serbia, wanted more help. This created arguments about money and fairness.

- Weakening of Communism: When Mikhail Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, tensions with the West eased. This meant Western countries no longer needed Yugoslavia as a buffer state, so they were less willing to help with its debts. The fall of communism across Eastern Europe also showed that Yugoslavia's system was struggling.

Rise of Nationalism in Serbia (1987–1989)

Slobodan Milošević's Influence

In 1987, a Serbian politician named Slobodan Milošević went to Kosovo to address protests by Serbs who felt mistreated by the Albanian administration there. Milošević, who had previously been against nationalism, saw an opportunity. He promised Serbs that their problems would be solved and began to push for less autonomy for Kosovo and Vojvodina. This made him very popular among Serbs. He promised to protect all Serbs and strengthen Serbia's position within Yugoslavia.

Milošević quickly became the most powerful politician in Serbia. He openly stated that Serbia's enemies were gathering against them, and that Serbs would not be afraid to fight. He also privately said that Serbs would act in Serbia's interest, whether it followed the rules or not.

Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution

Milošević organized a series of protests called the "Anti-bureaucratic revolution." These protests helped him put his supporters in power in Vojvodina, Kosovo, and Montenegro. This meant that Milošević could now control four out of eight votes in the Yugoslav Presidency, which was the country's collective leadership. This gave him a lot of power to block decisions he didn't like.

In February 1989, Albanian miners in Kosovo went on strike, demanding that their autonomy be protected. This led to more ethnic conflict. Milošević's supporters saw this as a "counter-revolution" and demanded that the federal government use force to stop the strike.

In June 1989, on the 600th anniversary of the historic Battle of Kosovo, Milošević gave a famous speech to 200,000 Serbs. He used strong nationalist language, reminding Serbs of their medieval history. He wanted to centralize the government, which was the opposite of what Slovenia and Croatia wanted.

Reactions to Milošević's Actions

Slovenia and Croatia supported the Albanian miners. Slovenian media even compared Milošević to Benito Mussolini, a fascist dictator. Milošević's state-run media accused Slovenian leaders of supporting separatism.

When Albanian protests grew, Milošević and his allies pushed the federal government to use the army in Kosovo. In February 1989, an Albanian representative in the Presidency was forced to resign and was replaced by a Milošević ally. Albanian protesters demanded his return. Milošević called this a "counter-revolution" and demanded military action.

On February 27, the Slovenian representative, Milan Kučan, opposed the Serbian demands. He went to a meeting in Slovenia and publicly supported the Albanian protesters. He worried that if Milošević succeeded in Kosovo, Slovenia would be next. Serbian state TV called Kučan a traitor.

Milošević used large protests in Belgrade to pressure the Yugoslav government. He told the crowds that Serbs were winning their fight against old leaders. He promised that anyone working against Yugoslavia's unity would be arrested. Soon after, the Yugoslav army entered Kosovo, and the Albanian representative was arrested.

In March 1989, Serbia changed its constitution to take back control over Kosovo and Vojvodina. These regions had previously made many of their own political decisions and had votes in the Yugoslav Presidency.

An attempt by Milošević's supporters to hold a similar protest in Slovenia in December 1989 failed. Croatian police blocked the trains carrying Serb protesters, preventing them from reaching Slovenia.

Final Political Crisis (1990–1992)

The Communist Party Breaks Up

In January 1990, the main communist party of Yugoslavia held a big meeting. The Serbian and Slovenian groups argued about the future of the party and the country. Milošević's Serbian group wanted a "one person, one vote" system, which would give more power to the Serbs because they were the largest ethnic group.

But Croatia and Slovenia wanted to give more power to the six republics. They were outvoted on every proposal. As a result, the Croatian and Slovenian groups left the meeting on January 23, 1990. This effectively broke up the main Yugoslav party. This event, along with outside pressure, led to multi-party elections in all the republics.

Multi-Party Elections

In 1990, republics held their own multi-party elections. In Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, nationalist parties won. These parties promised to protect their own national interests. In Montenegro and Serbia, the former communist parties, now rebranded, won. Milošević was re-elected president of Serbia. This meant Serbia and Montenegro increasingly favored a Yugoslavia dominated by Serbs.

Tensions in Croatia

In Croatia, the nationalist Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) won, led by Franjo Tuđman. He promised to protect Croatia from Milošević and pushed for Croatian independence. Serbs living in Croatia were worried about Tuđman's government. In 1990, Serb nationalists in the town of Knin formed a separate group called the SAO Krajina. They wanted to stay with Serbia if Croatia became independent.

The Serbian government supported these Croatian Serbs. They claimed that being under Tuđman's rule would be like the terrible times for Serbs during World War II. Milošević used this to rally Serbs against the Croatian government.

Croatian Serbs in Knin started gathering weapons to rebel against the Croatian government. They met with Borisav Jović, the head of the Yugoslav Presidency, and asked him to stop Croatia from leaving Yugoslavia. An army official even told them how to organize their rebellion, suggesting they use hunting rifles if nothing else was available.

The revolt became known as the "Log Revolution" because Serbs blocked roads with cut-down trees. This hurt tourism in Croatia. The Croatian government tried to stop the rebellion by sending special forces, but the federal Yugoslav Air Force intervened and forced the Croatian helicopters to turn back. This showed Croatia that the Yugoslav People's Army was increasingly controlled by Serbia. The SAO Krajina officially declared itself a separate entity on December 21, 1990.

Slovenia and Croatia Declare Independence

In a vote held on December 23, 1990, most people in Slovenia voted for independence. Slovenia declared its independence on June 25, 1991.

In January 1991, a secret video was shown that seemed to show Croatia's Defence Minister talking about smuggling weapons and fighting the Yugoslav army. This made the army want to charge him with treason.

The discovery of Croatian arms smuggling, along with the problems in Knin and the election of independence-minded governments, showed that Yugoslavia was about to break apart.

On March 1, 1991, a conflict happened in Pakrac, and the Yugoslav army was sent there. On March 9, protests in Belgrade were stopped with the help of the army.

On March 12, 1991, army leaders met with the Yugoslav Presidency. They wanted to declare a state of emergency, which would let the army take control of the country. The army chief said there was a plot to destroy Yugoslavia. The Croatian representative, Stjepan Mesić, angrily said this meant war. A vote was held on whether to allow military rule, but it was rejected.

The Yugoslav presidency became stuck because Milošević's Serbian group had enough votes to block any decisions they didn't like. This made other republics demand changes to the Yugoslav system.

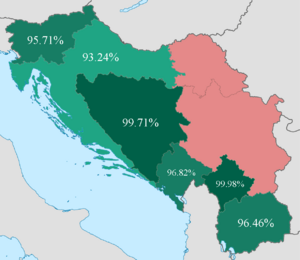

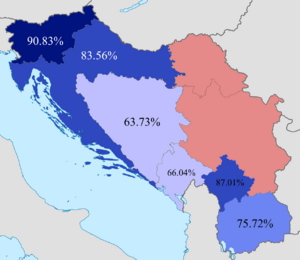

In a vote on May 19, 1991, 93.24% of people in Croatia voted for independence. Croatian Serbs mostly did not participate in this vote. Croatia declared its independence on June 25, 1991.

The Start of the Yugoslav Wars

War in Slovenia (1991)

Both Slovenia and Croatia declared independence on June 25, 1991. Yugoslavia's Constitutional Court said this was against the rules, as all republics had to agree to a secession.

On June 26, Yugoslav army units moved towards Slovenia's borders. Slovenians quickly set up roadblocks and protests. There was no fighting at first. Slovenia had already taken control of its airports and border posts. Since many border guards were already Slovenian, it was mostly a change of uniforms. By controlling the borders, Slovenia was ready for an attack. The first shot was fired by a Yugoslav army officer on June 27.

The European Community (a group of European countries) asked Slovenia and Croatia to pause their independence for three months. They reached an agreement on July 7, 1991. During this time, the Yugoslav Army left Slovenia completely.

Negotiations to save Yugoslavia failed. A plan was proposed that recognized Yugoslavia was breaking up and that each republic should become independent. It also promised to protect Serbs living outside Serbia. Milošević refused this plan, saying it would divide the Serb people.

Germany then decided to recognize Slovenia and Croatia as independent on Christmas Eve 1991, which surprised many other countries. This recognition, along with Austria's actions, likely made the situation worse for Yugoslavia.

War in Croatia (1991)

The Croatian War of Independence began in late March/early April 1991. It was fought between the Croatian government and rebel ethnic Serbs in the SAO Krajina, who were strongly supported by the Serb-controlled Yugoslav People's Army. On April 1, 1991, the SAO Krajina declared it would separate from Croatia. Other Serb-dominated areas in Croatia also joined them, forming the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina on December 19, 1991.

Croatia stopped sending tax money to Belgrade, and the Croatian Serb areas stopped paying taxes to Croatia. In some places, the Yugoslav Army acted as a buffer, while in others, it helped Serbs fight the new Croatian army.

Propaganda from both sides spread fear and hatred. The Serb-dominated Yugoslav army and navy shelled civilian areas like Dubrovnik, a famous historical city. Yugoslav media claimed this was because of "fascist forces" there, but UN investigations found no such forces.

In Vukovar, violence erupted when the Yugoslav army entered the town. The town was heavily damaged, and Serb paramilitary groups committed violence against Croats, killing over 200 people and forcing many to leave.

Independence of Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina had a mixed population of Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats. This made the ownership of land a big problem.

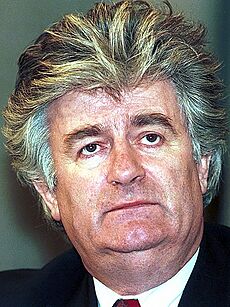

From 1991 to 1992, the situation in Bosnia became very tense. Its parliament was divided along ethnic lines. In October 1991, Radovan Karadžić, the leader of the Serb group, warned that if Bosnia separated, it would lead to a "highway of hell and death."

Behind the scenes, leaders from Serbia and Croatia discussed dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbs and Croats. Bosnian Serbs held a vote in November 1991, and most voted to stay in a common state with Serbia and Montenegro.

On January 9, 1992, the Bosnian Serb assembly declared a separate Republic of the Serb people of Bosnia and Herzegovina (later called Republika Srpska). They also formed Serb autonomous regions. The Bosnian government said these actions were against the constitution.

A vote on independence was held in Bosnia on February 29 and March 1, 1992. Bosnian Serbs largely boycotted it. The official results showed that 99.7% of those who voted were for independence.

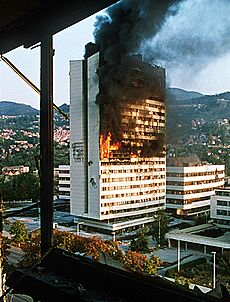

Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on March 3, 1992, and was recognized by other countries on April 6, 1992. On the same day, Serbs declared the independence of Republika Srpska and began the Siege of Sarajevo, starting the Bosnian War. Bosnia and Herzegovina became a member of the United Nations on May 22, 1992.

NATO airstrikes against Bosnian Serb targets helped lead to the Dayton Agreement on December 14, 1995, which ended the conflict. Around 100,000 people died in the war.

Macedonia

In a vote on September 8, 1991, 95.26% of people in Macedonia voted for independence. Macedonia declared independence on September 25, 1991.

Five hundred US soldiers were sent to monitor Macedonia's border with Serbia. Belgrade did not try to stop Macedonia from leaving or protest the UN troops. This showed that Serbia would recognize Macedonia once it formed its new country. As a result, Macedonia was the only former republic to gain independence without fighting the Yugoslav authorities.

Macedonia's first president, Kiro Gligorov, kept good relations with Belgrade and the other former republics. There have been no border problems between Macedonia and Serbia.

International Recognition of the Breakup

While many European countries wanted Yugoslavia to stay united, Germany's leader, Helmut Kohl, pushed for the recognition of Slovenia and Croatia. He threatened sanctions if the federal government used military force. On Christmas Eve 1991, Germany recognized Slovenia and Croatia's independence, against the advice of other countries and the UN.

In November 1991, a special commission concluded that Yugoslavia was breaking up. It also said that Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia did not have the right to form new states, and that the borders between the republics should become international borders. The United Nations Security Council then voted to allow peacekeeping operations in Yugoslavia.

On January 15, 1992, the international community recognized the independence of Croatia and Slovenia. Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina later joined the United Nations on May 22, 1992. Macedonia joined on April 8, 1993, but its membership took longer due to objections from Greece.

Some people believe that the breakup of Yugoslavia could have been less violent if other countries had done more to ensure the safety of all groups.

What Happened Next in Serbia and Montenegro

Bosnia and Herzegovina's independence was the final step in the breakup of the old Yugoslavia. On April 28, 1992, Serbia and Montenegro formed a new country called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). This country was mostly controlled by Slobodan Milošević. Its government claimed to be the continuation of the old Yugoslavia, but other countries did not agree. They said Yugoslavia had dissolved into separate states. The FRY was not allowed to keep Yugoslavia's seat at the United Nations.

The breakup and wars led to sanctions against the FRY, which caused its economy to collapse. The wars in the western parts of former Yugoslavia ended in 1995 with peace talks in Dayton, Ohio. The Kosovo War started in 1998 and ended with NATO bombings in 1999. Slobodan Milošević was removed from power in 2000.

The FRY finally gave up its claim to be the continuation of the old Yugoslavia in 1996. After Milošević was overthrown, the FRY rejoined the United Nations in 2000. An agreement was signed in 2001 to share Yugoslavia's international assets among the five new independent states.

On February 4, 2003, the FRY changed its name to the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. This union also broke up in 2006, when Montenegro voted for independence. Serbia then inherited the State Union's UN membership.

Kosovo has been under international administration since 1999.

Images for kids

-

Serbian President Slobodan Milošević's unequivocal desire to uphold the unity of Serbs, a status which was threatened by each republic breaking away from the federation, in addition to his opposition to the Albanian authorities in Kosovo, further inflamed ethnic tensions.

-

Croatian President Franjo Tuđman

-

Bosnian Muslim leader Alija Izetbegović

-

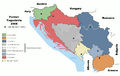

State entities on the former territory of SFR Yugoslavia, 2008.