Easter Island facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Easter Island

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Outer slope of the Rano Raraku volcano, the quarry of the Moais with many uncompleted statues.

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Country | Chile | ||||

| Region | Valparaíso | ||||

| Province | Isla de Pascua | ||||

| Commune | Isla de Pascua | ||||

| Seat | Hanga Roa | ||||

| Government | |||||

| • Type | Municipality | ||||

| • Body | Municipal council | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total | 163.6 km2 (63.2 sq mi) | ||||

| Highest elevation | 507 m (1,663 ft) | ||||

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) | ||||

| Population

(2017 census)

|

|||||

| • Total | 7,750 | ||||

| • Density | 47/km2 (120/sq mi) | ||||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (EAST) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (EASST) | ||||

| Country Code | +56 | ||||

| Currency | Peso (CLP) | ||||

| Language | Spanish, Rapa Nui | ||||

| Driving side | right | ||||

| NGA UFI=-905269 | |||||

Easter Island is a faraway Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. Its capital city is Hanga Roa.

The island is famous for its 887 huge stone statues called Moai. These were carved by the early Rapa Nui people. Easter Island also has a large crater called Rano Kau. Inside this crater is a natural lake, one of only three sources of fresh water on the island.

Easter Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A large part of the island is protected as the Rapa Nui National Park.

In the 1800s, diseases brought by European visitors and slave raids greatly reduced the island's population. Also, animals like rats and sheep, brought to the island, caused the loss of many native plants.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Easter Island" was given by the first European visitor to record his arrival. This was a Dutch explorer named Jacob Roggeveen. He found the island on Easter Sunday (April 5), 1722. He was looking for "Davis Land" at the time. Roggeveen named it Paasch-Eyland, which means "Easter Island" in old Dutch. The island's official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, also means "Easter Island."

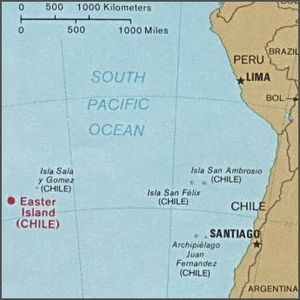

Where is Easter Island?

Easter Island is one of the most isolated islands in the world where people live. Its closest inhabited neighbor is Pitcairn Island. This island is about 1,931 kilometers (1,200 miles) to the west and has only about 50 people. The nearest part of a continent is in central Chile, near Concepción, about 3,512 kilometers (2,182 miles) away.

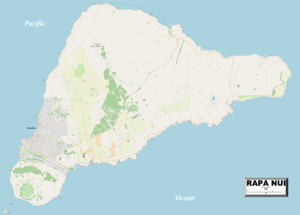

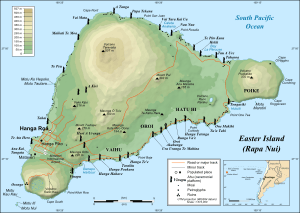

The island is shaped like a triangle. It is about 24.6 kilometers (15.3 miles) long and 12.3 kilometers (7.6 miles) wide at its widest point. Its total area is 163.6 square kilometers (63.2 square miles). The highest point on the island is 507 meters (1,663 feet) above sea level. There are three freshwater crater lakes on the island. These are at Rano Kau, Rano Raraku, and Rano Aroi. There are no permanent streams or rivers.

Climate and Weather

The weather on Easter Island is subtropical maritime. This means it's usually warm and humid. The coolest months are July and August, with temperatures around 18°C (64°F). The warmest month is February, with temperatures reaching up to 28°C (82°F). Winters are quite mild. April is the rainiest month, but it rains throughout the year.

Island Life and Nature

Easter Island, along with its neighbor Isla Salas y Gómez, is known as a special ecoregion. Long ago, the island was covered in subtropical moist forests. Studies of old plant remains show that many trees, shrubs, ferns, and grasses grew there.

A large, now extinct palm tree, Paschalococos disperta, was common. The Polynesian rat, brought by the first settlers, also played a part in the palm's disappearance. However, evidence shows that humans cut down many trees.

The toromiro tree (Sophora toromiro) also used to grow on Easter Island but is now extinct in the wild. Efforts are being made to bring it back to the island. With fewer trees, there was less rainfall. For almost a century, the island was used for sheep farming. By the mid-1900s, it was mostly covered in grassland.

Before humans arrived, Easter Island had huge seabird colonies. There were probably over 30 different species, making it one of the richest places for seabirds. Today, these colonies are not found on the main island.

History of Easter Island

Experts believe that Easter Island was first settled around 1200 CE. This was likely around the same time that Hawaii was settled. New dating methods have changed earlier ideas about when Polynesia was first settled.

Oral traditions say the first settlement was at Anakena. This spot offers good shelter and a sandy beach for canoes. However, some studies suggest other places were settled earlier.

The island was populated by Polynesians. They likely traveled in canoes or catamarans from islands like the Gambier Islands or the Marquesas Islands. Some theories suggest early Polynesian settlers might have come from South America. This idea comes from the presence of the sweet potato, a crop from South America, which was important in Polynesian culture. However, recent research suggests sweet potatoes might have spread naturally. When James Cook visited, a Polynesian crew member could talk with the Rapa Nui people. This shows their shared language roots.

Old stories say the island once had a strong class system. A high chief, called an ariki, had great power. The most noticeable part of their culture was making the huge moai statues. Many believe these statues honored important ancestors or chiefs. People thought the dead helped the living with health and good fortune. In return, the living honored the dead with offerings. Most settlements were on the coast, and most moai faced inland, watching over their people.

As the island became crowded and resources became scarce, warriors gained more power. The worship of ancestors changed to the Bird Man Cult. This cult believed that a human chosen through a competition could contact the dead. The god Makemake, who created humans, was important in this. Competitions for the Bird Man (Rapa Nui: tangata manu) began around 1760 and ended in 1878.

European Visitors

The first European to record visiting the island was Dutch sailor Jacob Roggeveen on April 5, 1722. His visit led to the death of about a dozen islanders.

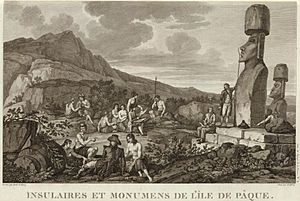

Later, on November 15, 1770, two Spanish ships visited. The Spanish were amazed by the "standing idols," which were all upright then.

Four years later, in 1774, British explorer James Cook visited. He reported that some statues had fallen. He learned that the statues honored former high chiefs.

On April 10, 1786, French Admiral Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse anchored at Hanga Roa. He made detailed maps of the bay and the island.

The 1800s

The 1860s brought terrible events to the island. In December 1862, slave raiders from Peru captured about 1,500 people. This was half of the island's population. Among those taken were the island's chief and people who could read the unique rongorongo script.

When the slave raiders were forced to return the people, they brought diseases like smallpox. This caused terrible epidemics on Easter Island and other islands. The population of Easter Island dropped so much that some people were not even buried.

Tuberculosis, brought by whalers, also killed many islanders. The population continued to shrink. By 1877, only 111 people lived on Easter Island. This meant much of the island's cultural knowledge was lost.

Alexander Salmon, Jr. helped bring back some workers. He eventually bought most of the land on the island. He worked to develop tourism and shared information with British and German explorers. He sold his land to the Chilean government on January 2, 1888.

Easter Island became part of Chile on September 9, 1888. This happened through a treaty signed by Policarpo Toro for Chile and Atamu Tekena, who was called "King" by the missionaries.

The 1900s

Until the 1960s, the Rapa Nui people were mostly limited to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was used as a sheep farm. The Chilean Navy then managed the island until 1966. In 1966, the island was fully opened, and the Rapa Nui people became Chilean citizens.

After a change in government in Chile in 1973, Easter Island was placed under military rule. Tourism slowed down. Land was divided and given to investors. The military built new facilities.

In 1985, Chile and the United States agreed to make the runway at Mataveri International Airport larger. It was finished in 1987.

The 2000s

Fishers on Rapa Nui have worried about illegal fishing. They say that since 2000, tuna, a main fish, has become scarce.

On July 30, 2007, a new law made Easter Island a "special territory" of Chile. This helps preserve its unique culture and environment.

In 2018, the government decided to limit how long tourists can stay. This changed from 90 to 30 days. This was done to help protect the island's environment and history.

Culture of Easter Island

The Rapa Nui people have many interesting myths and traditions:

- Tangata manu, the Birdman cult, was practiced until the 1860s.

- Makemake is an important god.

- Aku-aku are guardians of sacred family caves.

- Moai-kava-kava is a ghost man from the Hanau epe (long-ears) legends.

Stone Work

The Rapa Nui people were skilled stone workers. They used local stones for their creations:

- Basalt: A very hard stone used for tools called toki and some moai.

- Obsidian: A sharp volcanic glass used for tools and the black parts of moai eyes.

- Red scoria: A light red stone from Puna Pau used for the pukao (topknots) on moai.

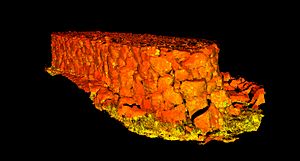

- Tuff: A softer rock from Rano Raraku used for most of the moai.

Moai (Statues)

The huge stone statues, or moai, are what Easter Island is most famous for. They were carved between 1100 and 1680 CE. There are 887 moai found on the island and in museums. While often called "Easter Island heads," most statues have bodies that end at the thighs. A few are full figures kneeling with hands on their stomachs. Some upright moai are buried up to their necks by soil.

Almost all moai (95%) were carved from volcanic ash or tuff. This stone was found at one place: the side of the extinct volcano Rano Raraku. The islanders used only stone hand chisels, mostly basalt toki. These chisels were sharpened by chipping off new edges. While carving, water was splashed on the stone to soften it. A team of five or six men took about a year to finish one moai. Each statue likely represented a deceased leader of a family group.

Only about a quarter of the statues were ever put in place. Nearly half stayed in the quarry at Rano Raraku. The rest were left elsewhere, probably on their way to their planned spots. The largest moai placed on a platform is called "Paro." It weighs 82 tons and is 9.89 meters (32 feet 5 inches) long.

People think the statues were moved using a Y-shaped sledge called a miro manga erua. Ropes made from tough tree bark were tied around the statue's neck. It took 180 to 250 men to pull, depending on the moai's size. Some researchers have recreated how the moai might have been moved. About 50 statues have been re-erected in modern times.

Another idea is that the moai were rocked forward by attaching ropes and pulling. This fits the legend that the moai "walked" to their final places. This method might have needed as few as 15 people. Evidence for this includes:

- Moai in the quarry have heads tilted forward, which would help with balance during transport.

- Statues found on the transport roads have wider bases for stability.

- Fallen statues are often found face down when going downhill and on their backs when going uphill.

There is a discussion about how making these monuments affected the environment. Some believe that carving the moai led to widespread deforestation and even civil war over limited resources.

In 2011, a large moai was dug out of the ground. During this digging, some larger moai were found to have detailed carvings on their backs.

- Moais

-

Tukuturi, an unusual kneeling moai with a beard.

-

All fifteen standing moai at Ahu Tongariki, restored in the 1990s.

-

Ahu Akivi, one of the few inland ahu, with the only moai facing the ocean.

Ahu (Stone Platforms)

Ahu are stone platforms. They vary greatly in design. Many were changed after the moai were toppled. Of the 313 known ahu, 125 once held moai. Ahu Tongariki, about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) from Rano Raraku, had the most and tallest moai, 15 in total. Other important ahu with moai include Ahu Akivi and Nau Nau at Anakena.

The main parts of an ahu are:

- A high back wall, usually facing the sea.

- A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs.

- A red stone covering over the front wall (for platforms built after 1300).

- A sloping ramp on the inland side.

- A pavement of round, water-worn stones.

- A paved open area in front of the ahu, called a marae.

- The inside of the ahu was filled with rubble.

On top of many ahu, you would find:

- Moai on square bases, looking inland.

- Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau (red topknots) on the moai heads (for platforms built after 1300).

- During ceremonies, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The white parts were made of coral, and the colored parts were made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu developed from the traditional Polynesian marae. On Easter Island, ahu and moai grew to be much larger. The biggest ahu is 220 meters (720 feet) long and holds 15 statues, some 9 meters (30 feet) high.

Ahu are mostly found along the coast. There are fewer on the western slopes of Mount Terevaka and the Rano Kau and Poike headlands. These areas have less coastal land and are further from Rano Raraku.

Stone Walls

One of the best examples of stone work on Easter Island is the back wall of the ahu at Vinapu. It was built without mortar, using hard basalt rocks weighing up to 7,000 kilograms (7.7 tons). These rocks were shaped to fit together perfectly. This wall looks similar to some Inca stone walls in South America.

Stone Houses

Two types of houses were common in the past:

- Hare paenga: Houses with an oval base, made from basalt slabs and covered with a thatched roof that looked like an overturned boat.

- Hare oka: Round stone structures.

Similar stone buildings called Tupa were lived in by astronomer-priests. They were located near the coast to observe the stars. Settlements also had hare moa ("chicken house"), which were long stone buildings for chickens. The houses at the ceremonial village of Orongo are unique. They are shaped like hare paenga but are made entirely of flat basalt slabs from inside the Rano Kao crater. The entrances to all these houses are very low, so you have to crawl to get in.

In early times, the Rapa Nui people reportedly sent their dead out to sea in small canoes. Later, they buried people in secret caves to protect the bones from enemies. During difficult times in the late 1700s, islanders started burying their dead near fallen moai statues. During epidemics, they made large stone structures for mass graves.

Petroglyphs

Easter Island has one of the largest collections of petroglyphs (rock carvings) in Polynesia. About 1,000 sites with more than 4,000 carvings have been found. Designs and images were carved for different reasons, like creating symbols, marking land, or remembering a person or event. Many Birdman carvings are found at Orongo. Other carvings show sea turtles and the chief god of the Tangata manu or Birdman cult.

- Petroglyphs

-

Fish petroglyph found near Ahu Tongariki.

Caves

Easter Island and the nearby islet Motu Nui have many caves. Many show signs that people used them in the past for planting and as hiding places. Some have narrow entrances and crawl spaces for defense. Many caves are part of Rapa Nui myths and legends.

Other Stones

The Pu o Hiro or Hiro's Trumpet is a stone on the north coast. It was once a musical instrument used in special ceremonies.

Rongorongo

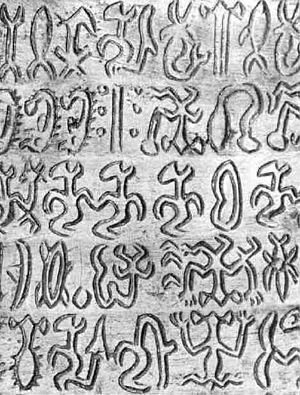

Easter Island once had a special writing system called rongorongo. The symbols include pictures and geometric shapes. The texts were carved into wood. It was first reported in 1864. At that time, some islanders said they could understand the writing. However, only ruling families and priests were said to know it, and none survived the slave raids and diseases. Despite many attempts, the remaining texts have not been fully understood. Only about two dozen texts still exist, none on the island itself.

Wood Carving

Wood was rare on Easter Island in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many detailed and unique wood carvings have been found in museums around the world. Some special types include:

- Reimiro: A crescent-shaped chest ornament with a head at one or both ends. This design is also on the flag of Rapa Nui. Some Reimiro have Rongorongo carvings.

- Moko Miro: A figure of a man with a lizard head. It was used as a club or worn by dancers. It was also placed at doorways to protect homes.

- Moai kavakava: Carvings of male figures. Moai Paepae are female carvings. These detailed figures, carved from Toromiro pine, represent ancestors. They were sometimes used in fertility rituals or harvest celebrations. When not in use, they were wrapped in cloth and kept at home. The figures often show thin bodies with ribs and bones visible. The more figures a man wore, the more important he was.

- Ao: A large dancing paddle.

Interesting Facts About Easter Island

- Easter Island is one of the most remote islands in the world where people live.

- Along with the Juan Fernández Islands, it has a special "territory" status in Chile since 2007.

- Old stories say the island was first called Te pito o te kainga a Hau Maka, meaning "The little piece of land of Hau Maka." But pito can also mean "navel," so it can also mean "The Navel of the World." Another name, Mata ki te rangi, means "Eyes looking to the sky."

- In 1995, UNESCO named Easter Island a World Heritage Site.

- Easter Island is the only place in Polynesia where Spanish is an official language.

Images for kids

-

View of Rano Kau and the Pacific Ocean.

See also

In Spanish: Isla de Pascua para niños

In Spanish: Isla de Pascua para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |