Ed Schieffelin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Schieffelin

|

|

|---|---|

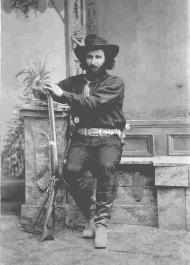

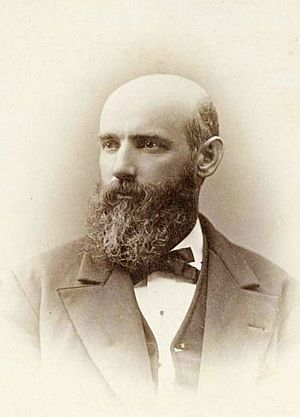

Schieffelin in 1882

|

|

| Born | 1847 |

| Died | May 12, 1897 (aged 49–50) |

| Occupation | Indian scout, prospector |

| Known for | Discovery of silver in the Arizona Territory |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Brown |

| Signature | |

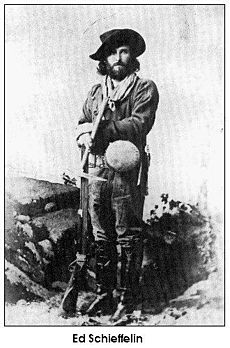

Edward Lawrence Schieffelin (1847–1897) was an Army scout and prospector. He is famous for finding silver in the Arizona Territory. This discovery led to the creation of the famous town of Tombstone, Arizona. Ed, his brother Al, and a mining engineer named Richard Gird made a deal with a handshake. This partnership brought in millions of dollars for all three men. Over time, the mines in Tombstone produced about $85,000,000 worth of silver.

Contents

Early Life

Ed Schieffelin was born in 1847 in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania. This area was known for coal mining. His family was well-known in New York and Pennsylvania. His great-grandfather, Jacob Schieffelin, Sr., was a Loyalist during the American Revolutionary War. He later started a drug company in New York.

In the mid-1850s, Ed's father, Clinton Emanuel Del Pela Schieffelin, moved his family to the Rogue Valley in the Oregon Territory. There, they raised cattle and crops. The family was also interested in mining activities in the area.

The Hunt for Gold and Silver

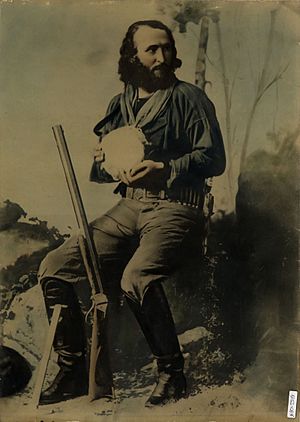

When Ed was 17, he started his own journey as a prospector. He began searching for gold and silver around 1865. He traveled from Oregon to Idaho, then across Nevada, and into Colorado and New Mexico. He was always looking for valuable minerals.

In 1877, at age 30, Schieffelin moved to California to search for gold. He also explored the Grand Canyon area. He didn't find much luck there. He then heard that Hualapai Native Americans were helping the U.S. Army as scouts. The Army was setting up a camp to deal with the Chiricahua Apache and protect the border with Mexico. This camp, Camp Huachuca, was set up in Arizona on March 3, 1877. Silver had been found in northern Arizona, but the southern part was still dangerous due to Apache attacks.

Schieffelin went with the scouts on some trips. He also prospected part-time. He decided to stay and explore the hills to the east. These hills, near the San Pedro River, were risky. They were only about 12 miles (19 km) from where hostile Chiricahua Apache, led by Cochise and Geronimo, lived.

Finding the Ore

Years before, in 1858, a mining engineer named Frederick Brunckow had found silver in these hills. He built a cabin near the San Pedro River. This discovery encouraged Ed Schieffelin to search the rocky areas northeast of the cabin.

A friend and fellow army scout, Al Sieber, warned Ed. He reportedly told him, "The only rock you will find out there will be your own tombstone." Other friends said, "Better take your coffin with you; you will find your tombstone there, and nothing else."

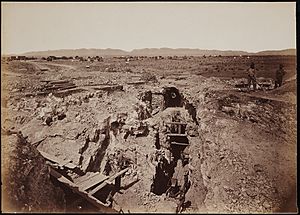

In 1877, Schieffelin used Brunckow's cabin as his base. After many months, he was exploring the hills east of the San Pedro River. He found pieces of silver ore in a dry streambed on a high flat area called Goose Flats. It took him several more months to find where the silver came from. When he found the main vein, he thought it was 50 feet (15 m) long and 12 inches (30 cm) wide. Schieffelin named his first mining claim "Tombstone." This name was a nod to his friends' warnings.

Ed was broke, but he convinced William Griffith to pay for the legal papers to file his claim on September 3, 1877. There was no assay office in Tucson. When they showed the ore samples to local men, they thought the silver was worthless.

With only 30 cents, Schieffelin went to find his brother Al. He hadn't seen Al in four years. He thought Al was at the Silver King mine, about 180 miles (290 km) north. But Al had moved to the McCracken Mine, another 300 miles (480 km) north. Ed spent his 30 cents on tobacco. He had to stop searching for his brother to earn more money. He found a job at the Champion silver mine. For two weeks, he hauled tons of ore every night.

A New Partnership

Ed finally found his brother Al in February 1878. Al asked his foreman at the McCracken mine to look at Ed's ore samples. The foreman thought they were mostly lead. Ed was not convinced. He showed the samples to many other experts, but they all thought the ore was worthless. Frustrated, Ed threw his samples out his brother's cabin door. But he held onto three of them at the last moment. For the next month, he worked in the McCracken Mine.

Ed then heard about the McCracken Mine's new assayer, Richard Gird. Gird was known as an expert. Ed took his last three ore samples to Gird. He asked if they were worth testing. Gird looked at them and said he would get back to Ed. Three days later, Al woke Ed up. Gird wanted to see him right away. Gird told Ed that the best ore sample was worth $2,000 a ton!

Ed, Al Schieffelin, and Richard Gird immediately formed a partnership. Gird offered his knowledge, contacts, and money for supplies. They shook hands on their three-way deal. This gentlemen's agreement was never written down. But it made millions of dollars for all three men. Gird's employer offered him a promotion, but he turned it down.

Gird bought a wagon and loaded it with supplies and his assay equipment. He also bought a second mule to pull the wagon. Gird wanted to wait for spring and better weather. But Ed insisted they leave right away. Al hesitated to leave his good job as a miner. Ed and Gird didn't wait. They left that day. Al changed his mind and joined them that night. They returned to Cochise County in Arizona. They set up camp at the Brunckow cabin. There were fresh graves near the cabin, showing that Apache attacks were still happening.

The three partners created the Tombstone Gold and Silver Mining Company. This company would own their claims. Gird built a simple furnace in the cabin's fireplace. He found that Ed's first silver ore was valuable. But after a few weeks of mining, Ed found the vein ended. His brother Al and Gird were sad. But Ed was hopeful he could find more ore. He kept searching for many more weeks. One day, Al found Ed happily showing off another ore sample. Al simply called Ed a "lucky cuss." This became the name of one of the richest mining claims in the Tombstone District. The ore samples were worth $15,000 a ton. Ed soon found another claim, the "Tough Nut" lode. It was rich in a type of silver called horn silver.

On June 17, 1879, Schieffelin arrived in Tucson. He was driving the wagon with the first load of silver. It was worth $18,744.

Tombstone is Founded

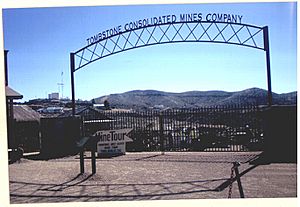

When the first claims were made, the first settlement was just tents and cabins. It was located at Watervale, near the Lucky Cuss mine. By March 1879, about 100 people lived in tents and shacks there. Former Governor Anson P.K. Safford offered to help them financially. Ed Schieffelin, his brother Al, and Richard Gird formed the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company. They built a mill to process the ore.

On March 5, 1879, a surveyor laid out a new town site. It was on a flat-topped hill called Goose Flats. This new town was named "Tombstone" after Schieffelin's first mining claim. The shelters from Watervale were moved to the new town. Cabins and tents were quickly built for about 100 residents.

During the first few months of mining, another part of the Tombstone mining area was found by accident. Ed Williams and Jack Friday lost their mules one night. The mules dragged their chain and left a trail to the Schieffelin camp. Williams and Friday saw a bright gleam where the chain had scraped the rock. They filed a claim for their find. But Al and Ed Schieffelin and Richard Gird said it violated their earlier claims. After arguing, they agreed to divide the land. Williams and Friday took the higher part, which they called the Grand Central. The Schieffelin company took the lower part, naming it the Contention. This name was a reminder of their quarrel. These two mines became the most profitable in Tombstone. Some ore from the "Lucky Cuss," "Tough Nut," and "Contention" mines was worth about $15,000 per ton.

Ed Schieffelin preferred finding new ore to running a mine. He left Tombstone to search for more. When he returned four months later, Gird had found buyers for their share in the Contention mine. They sold it for $10,000. The buyers thought this price was very high. But the Grand Central and Contention claims turned out to be the richest. They produced millions of dollars in silver. The Schieffelin company also sold half of the Lucky Cuss mine. The other half brought in a steady income.

On March 13, 1879, Al and Ed Schieffelin sold their two-thirds share in the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company. This company owned the Tough Nut mine. They sold it for US$1 million each to the Corbin brothers and others. Safford became president of the new company. Richard Gird became the superintendent. Ed moved on, but Al stayed in Tombstone for a while. Gird later sold his one-third share for US$1 million, which was double what the Schieffelins had been paid. Gird stayed in the area, but Ed Schieffelin left to pursue other interests.

In February 1881, Cochise County was formed. Tombstone became its main town. In 1881, as Tombstone grew quickly, Ed's brother Al built Schieffelin Hall. It was a theater, concert hall, and meeting place for the town. His great-niece Mary Schieffelin Brady reopened it in 1964. It is still a popular place in Tombstone. It is the largest adobe building still standing in the southwestern United States.

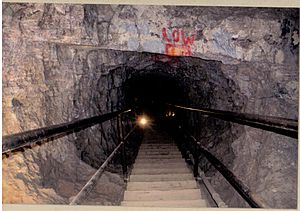

At its busiest in the mid-1880s, Tombstone had about 7,000 miners. Some estimates say there were also 5,000 to 7,000 more women, children, Chinese, and Mexican residents. In the late 1880s, the silver mines reached the water level. The mines eventually filled with water. Tombstone's population then decreased. Today, tourism is its main attraction.

Later Life

Ed had become very wealthy, with over $1 million from the silver boom. He had always looked casual, with long hair and a beard. But he cleaned himself up. He traveled to New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. He met many important people. Ed was always restless. For the next 20 years, he appeared in almost every new boom town in the West.

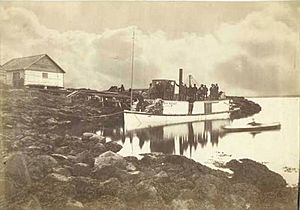

Schieffelin believed there was a huge "continental belt" of minerals. He thought it stretched from South America through Mexico, the United States, and British Columbia. In 1882, Ed prepared for a three-year trip to explore for minerals. He started the trip with his brother Al and three others. They went up the Yukon River in Alaska. They had a small steamboat built, which they named the New Packet. Ed prospected in Alaska and found some specks of gold. For a while, he thought he had found the "continental belt." But he was very discouraged by the extreme cold, which reached 50 degrees Fahrenheit below zero (-46 C). He decided that mining in Alaska was too difficult. He returned to the lower 48 states.

In 1883, he returned to San Francisco. There, he met Mary E. Brown. They married that same year in La Junta, Colorado. They spent part of the winter in Salt Lake City, Utah. In the spring of 1884, they returned to California. Ed built a large house for his wife in Alameda. They also bought a home in Los Angeles. They shared it with Ed's brother Al until Al died in 1885.

Ed's Final Days

In 1897, Schieffelin bought a ranch near his brothers Effingham and Jacob. It was outside Woodville, now Rogue River, Oregon. He continued to prospect in the Canyonville area, looking for gold and silver. On May 12, 1897, his neighbor checked on him. Ed had not come to town for supplies for several days. His neighbor found him on the floor of his miner's cabin. The coroner said he died of a heart attack. Ore samples found in his cabin were later said to be worth over $2,000 a ton. However, other reports from his family said they were only worth $7 per ton. Schieffelin did not leave a map showing where he found his last discovery. He was first buried near his cabin, about 20 miles (32 km) east of Canyonville.

It was later learned that he had asked to be buried in Tombstone. He wrote, "It is my wish, if convenient, to be buried in the dress of a prospector, my old pick and canteen with me, on top of the granite hills, about three miles westerly from the City of Tombstone, Arizona, and that a monument, such as prospectors build when locating a mining claim, be built over my grave." Schieffelin was buried about 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Tombstone, Arizona. This was near the dry streambed where he first found silver ore. It was also near the later Grand Central Mine. He was buried just as his will said: in mining clothes, with his pick, shovel, and old canteen. He left his property to his wife and his brother Jay. Mary Schieffelin moved to New York City after her husband's death.

Legacy

A 25-foot (7.6 m) tall monument stands near the spot of his original claim. It looks like the markers miners build to claim a discovery. The plaque on it reads, "Ed Shieffelin, died May 12, 1897, aged 49 years, 8 months. A dutiful son, a faithful husband, a kind brother, and a true friend." Years before, Schieffelin had written, "I never wanted to be rich, I just wanted to get close to the earth and see mother nature's gold." Schieffelin Gulch Road in the Rogue Valley, Oregon, is named after his family.

There are different ideas about how much gold and silver was mined in Tombstone. In 1883, one writer estimated that the mines produced about $25,000,000 in the first four years. Other estimates range from $40 million to $85 million. New mining is planned for the area in the future.

|

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |