Espenberg volcanic field facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Espenberg volcanic field |

|

|---|---|

Whitefish Maar

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Devil Mountain |

| Elevation | 797 ft (243 m) |

| Geography | |

| Geology | |

| Last eruption | Pleistocene |

The Espenberg volcanic field is a special area in Alaska with many volcanoes. It's famous for having the biggest maars on Earth. Maars are like wide, shallow craters that form when hot magma meets water or ice and causes a huge explosion.

This volcanic area was active a very long time ago, during the Pleistocene Ice Age. About 17,500 years ago, a massive eruption happened. It created the huge Devil Mountain Maar, which is about 8 by 6 kilometers (5 by 3.7 miles) wide. This eruption also spread volcanic ash, called tephra, over a huge area of 2,500 square kilometers (965 square miles). It even buried plants and trees!

Besides Devil Mountain Maar, other large maars in this field include North Killeak Maar, South Killeak Maar, and Whitefish Maar. There's also Devil Mountain itself, which is a type of volcano called a shield volcano. Scientists think these maars became so big because of how the hot magma reacted with the frozen ground, or permafrost, in Alaska.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The names of some of these places come from the Inupiaq language, spoken by local Native Alaskans. For example, "Killeak" means "East."

Devil Mountain Maar is also known as "Qitiqliik" or "Kitakhleek," which means "Double Lakes." Whitefish Maar is called "Narvaaruaq" or "Navaruk," meaning "Big Lake." Sometimes, this whole volcanic area is also called the Cape Espenberg-Devil Mountain volcanic field.

Where is Espenberg and What Does it Look Like?

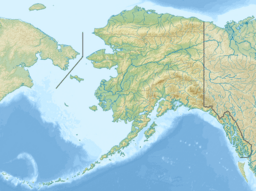

The Espenberg volcanoes are located on the northern part of the Seward Peninsula in Alaska. They are the northernmost volcanoes in North America that were active during the late Pleistocene Ice Age. They are just south of the Arctic Circle.

There are no roads directly to this area. However, you can reach the maars by following streams from the sea or by taking a special bush aircraft.

The Espenberg area is on a peninsula. The Chukchi Sea is to its north and west, and Goodhope Bay is to its east. If you look from east to west, you'll find North Killeak Maar, South Killeak Maar, Devil Mountain Maar, and Whitefish Maar.

Besides the maars, there are also smaller volcanoes called cinder cones, areas covered by lava flows, and five small shield-like volcanoes, like Devil Mountain. Devil Mountain itself seems to have a line of cinder cones on top, with lava flows around them.

The rocks from these volcanoes are mostly basalt, which is a common type of volcanic rock.

How Big Are These Maars?

Devil Mountain Maar is very large, about 8 kilometers (5 miles) long and 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) wide. It's also about 200 meters (656 feet) deep. North Killeak Maar is 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) wide, South Killeak Maar is 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) wide, and Whitefish Maar is 4.3 kilometers (2.7 miles) wide. The Killeak Maars are over 60 meters (197 feet) deep, but Whitefish Maar is much shallower, only about 6 meters (20 feet) deep.

These sizes make the Espenberg maars the largest on Earth! They are so big that they are similar in size to calderas, which are much larger volcanic craters. Most other maars around the world are much smaller.

Devil Mountain Maar is mostly round, but it's partly divided by a small sand spit. This spit separates it into two parts: the North Devil Mountain Maar (5.1 km wide) and the South Devil Mountain Maar (3.4 km wide). People used to think these were two separate maars.

The surface of the water in these maars is usually 60 to 80 meters (197 to 262 feet) below their rims. Inside Devil Mountain Maar, there are eight smaller, crater-like dips underwater, each about 0.1 to 1 kilometer (0.06 to 0.6 miles) wide and 50 to 100 meters (164 to 328 feet) deep. Similar dips, though partly filled, are also found in the Killeak Maars.

You can see layers of volcanic rock in cliffs around Devil Mountain Maar, which are 10 to 40 meters (33 to 131 feet) high. You can also see these layers in gullies around the other maars.

The maars formed in layers of old lavas and sediments from the Pleistocene age, which are over 300 meters (984 feet) thick. Several rivers flow through this volcanic area, including the Singeakpuk, Kalik, Kitluk, Espenberg, and Kongachuk Creek. The Kitluk River drains Devil Mountain Maar. Besides volcanoes, the landscape also has flat areas, thermokarst lakes (lakes formed by melting permafrost), dry lakes, and yedoma hills (hills made of ice-rich soil).

Life and People in Espenberg

The climate near the Espenberg volcanic field, in a town called Kotzebue, is very cold in winter and cool in summer. Temperatures can go from 11.9°C (53.4°F) in July to -20.2°C (-4.4°F) in January. It doesn't rain or snow much, about 230 millimeters (9 inches) per year, mostly in the summer.

The plants here are part of the Bering tundra ecoregion. You can find green alder bushes and willows on the maar benches. Near Tempest Lake, north of Devil Mountain Maar, the land is covered in tundra plants like forbs, mosses, sedges, and shrubs.

In the past, caribou were common in this area, and there are many fish in the maars.

Native Americans used these maars for fishing and hunting. Signs of human activity have been found along their shores. Devil Mountain was also used as a lookout spot, a landmark for navigation, and a place to find rocks for fishing weights.

More recently, scientists have taken core samples from the sediments at the bottom of North Killeak Maar and Whitefish Maar. These samples help them understand the past climate of the region, including cold periods. The Espenberg volcanoes are now part of the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, a protected area.

When Did These Volcanoes Erupt?

The volcanoes in Espenberg that are not maars seem to be very old, possibly over 500,000 years old. They are covered with plants, and their lava rocks are broken by frost. This suggests they are older than the maars.

At first, scientists thought the Espenberg maars were much younger. But new research shows that the most recent eruptions happened during the Pleistocene Ice Age. Scientists have used different ways to figure out their ages:

- Whitefish Maar might be between 100,000 and 200,000 years old, possibly around 160,000 years ago. Over time, sediment has partly filled in Whitefish Maar, making it shallower.

- North Killeak Maar is over 125,000 years old, making it older than South Killeak Maar.

- South Killeak Maar formed over 40,000 years ago.

- Devil Mountain Maar is the youngest. It formed about 17,500 years ago and was the most recent volcanic event in the area.

All the maars likely formed in a complex series of eruptions. For Devil Mountain Maar, the eruption probably only lasted a few weeks to months. During the eruption, there were many individual explosions. These explosions sent out fast-moving clouds of gas and ash, called base surges, and also threw out frozen blocks of dirt and rock. Devil Mountain Maar seems to have formed from several vents that joined together during the eruption. The smaller dips on the maar's floor were created by individual explosive events.

The eruption of Devil Mountain Maar spread a layer of volcanic ash, or tephra, called the Devil Mountain Lake tephra, over an area of 2,500 square kilometers (965 square miles). In some places, it was more than 1 meter (3.3 feet) thick over an area of 1,200 square kilometers (463 square miles). This ash buried soil and plants and fell into lakes.

The soil found under the Devil Mountain Maar tephra is called Kitluk paleosoil. Plant remains buried under the tephra are very well preserved. They have helped scientists learn about the climate and plants during the last glacial maximum in this region. It seems the plants back then were different from today, and there wasn't a lot of ice covering the land. This tephra is important for dating events in the late Pleistocene.

The eruptions of the Killeak Maars also produced tephra deposits. These are found in lakes and are similar to the tephra from Devil Mountain Maar. Their eruptions changed the local wetlands and the shape of the land.

How Maars Formed Here

Maars are the second most common type of volcano after cinder cones. They form when hot magma explodes as it meets water or ice underground. This explosion digs out a wide, but shallow, crater on the surface.

The Espenberg maars are special because they are the first known maars to have formed in permafrost (permanently frozen ground). Other large maars in permafrost have been found in Argentina. When magma meets ice, it's different from when it meets liquid water. Ice doesn't conduct heat well, and it takes a lot of energy to melt and turn into steam. So, the melting and explosive steaming happen slowly.

The maars are located in about 100 meters (328 feet) of permafrost. This permafrost was probably even thicker during the Pleistocene Ice Age when the maars formed. The large amount of ice would have produced a limited amount of water when the magma melted it. This created perfect conditions for very powerful explosions. These explosions might have been made even stronger by the release of methane gas as the permafrost thawed.

Landslides from the edges of the volcanic vents also helped make the craters bigger. These landslides brought more ice into the explosion area, which helped create the huge size of the Espenberg maars. The eruptions that formed the Espenberg maars happened during a fully glacial (cold, icy) climate. In contrast, eruptions during warmer periods on the Seward Peninsula have produced lava flows. This suggests that the cold, glacial climate affected the type of eruptions that took place.

Scientists have even used the Espenberg maars to understand certain craters found on Mars.

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |