Gweagal facts for kids

The Gweagal (also known as Gwiyagal) are an important group of the Dharawal people, who are Aboriginal Australians. Their families are the traditional caretakers of the southern parts of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Contents

Gweagal Country

The Gweagal people lived on the southern side of the Georges River and Botany Bay. Their land stretched towards the Kurnell Peninsula. While their exact borders are not fully known, their traditional lands may have reached from Cronulla as far west as Liverpool.

Gweagal Culture

The Gweagal people are the traditional owners of special white clay pits in their area. These pits are considered sacred places. In the past, this clay was used for many things. It lined the bottom of their canoes so they could light fires safely. It was also used as white body paint, which was seen by Captain James Cook.

They would add color to the clay using berries, making bright paints for ceremonies (special cultural events). The clay was also eaten as a medicine, like an antacid to help with stomach problems. They mixed Geebungs (a type of berry) and other local berries into the clay for this purpose.

Aboriginal Rock Shelters

The Gweagal people used natural caves and rock shelters. They used these places when they were on walkabout, which was a seasonal journey to care for their land and the "natural gardens" they looked after.

There is a large cave in Peakhurst with a ceiling blackened from smoke, showing it was used for fires. Other caves are found around Evatt Park in Lugarno. These caves have oyster shells ground into their floors. Another cave, now gone due to building, was found near Margaret Crescent in Lugarno. It contained ochre (colored earth) and a spearhead. There is also a cave on Mickey's Point in Padstow, named after a local Gweagal man.

The Gweagal decorated their caves and homes with carvings, sculptures, beads, paintings, drawings, and etchings. They used white, red, and other colored earth, clay, or charcoal. For example, a "water well" symbol with a red ochre hand would guide newcomers to water sources. Footprints in a line meant there were stairs or steps nearby.

Their homes and shelters were built to stay at a comfortable temperature all year. They used rugs, furs, and woven mats for warmth and comfort. Fire was important for cooking, making tools, and keeping their shelters warm.

Food Sources

The Gweagal's land provided plenty of food. The Georges River offered fish and oysters. Many small creeks, now mostly covered, gave them fresh water. Men and women fished from canoes or the shore. They used spears with barbs and fishing lines with hooks made from crescent-shaped shells.

They caught Waterfowl in the swampy areas near Towra Point. The different types of soil supported many edible and medicinal plants. Birds and their eggs, possums, wallabies, and goannas were also part of their regular diet. Because there was so much food, the Gweagal were less nomadic (moving from place to place) than Aboriginal people in Outback Australia.

Middens

Middens are heaps of shells, fish bones, and other waste. They have been found along the tidal parts of the Georges River. These middens, along with other signs like old dams and building foundations, show where the Gweagal people set up villages for long periods. These villages were often in places with oysters, fresh water, and good views. Middens have been found in Oatley, which was known as a feasting ground. In Lugarno, a midden still exists in Lime Kiln Bay.

First Contact with Europeans

The Gweagal people first saw Captain Cook and other Europeans on April 29, 1770. This happened in the area now called "Captain Cook's Landing Place," in the Kurnell part of Kamay Botany Bay National Park. This was the first time Cook tried to meet Aboriginal people in Australia during his first voyage on the Endeavour.

As the ship sailed into the bay, they saw two Gweagal men on the rocks with spears and fighting sticks. Four other men were busy fishing and didn't pay much attention to the ship. From offshore, Joseph Banks used a telescope and saw an elderly woman with six children light a fire near a camp of 6–8 gunyahs (shelters). She looked at the ship without seeming confused. The four fishermen joined her and cooked their catch.

After about an hour and a half, Cook, Banks, Daniel Solander, Tupaia, and 30 crew members went to the beach. They were met by two warriors. The Europeans threw some gifts ashore, trying to show they wanted fresh water. However, the Gweagal men were cautious and hostile. Cook tried to get their attention, and during this, one of the Gweagal men was injured. The injured man then got a shield from a gunyah and returned. By this time, the crew had already landed their boat.

The sailors then walked onto the beach and towards the camp. Both Cook and Banks tried hard to make contact with the local people, but the Gweagal avoided them after this first meeting. They continued their daily lives, seeming to ignore the strangers. They fished from canoes, cooked shellfish on the shore, and walked along the beach, but they watched Cook's crew carefully.

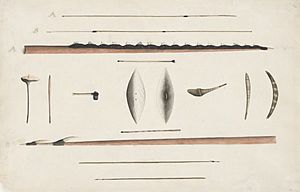

The Gweagal Spears and Shield

In 1770, after returning to England, Cook and Banks brought back many plants, animals, and cultural artefacts from their journey. This included about fifty Aboriginal spears that belonged to the Gweagal people. Banks believed the spears had been left behind on the shores of Kurnell.

According to Peter Turbet, four of these spears still exist today. They are important because they are some of the few items that can be traced back to Cook's first voyage. Cook gave the spears to his supporter, John Montagu. Montagu then gave them to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge in England. Even though Trinity College owns them, the spears are now on display at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge.

An Aboriginal shield held by the British Museum was thought to be the one dropped by a Gweagal warrior (named Cooman in Gweagal tradition). This warrior was injured by Cook's landing party on April 29, 1770. The shield was loaned to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra for an exhibition in 2015-2016.

Rodney Kelly, a descendant of Cooman, saw the exhibition and began a campaign to have the shield and the spears in Cambridge returned. He believes these items were stolen and are very important culturally. Kelly says the shield is a powerful symbol of how European explorers took over lands and how Indigenous people resisted.

In 2016, the British Museum offered to loan the shield to Australia, but the Gweagal people wanted it returned permanently. The NSW Legislative Council and the Australian Senate supported Kelly's claims. Kelly made several trips to the UK and Germany, where he found another shield at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin that was also said to be from Cook's 1770 visit.

The British Museum later investigated the shield's history. Experts studied the wood, museum records, and old shipping documents. They found that the shield's wood was red mangrove, which grows far north of Botany Bay. They also found that a hole in the shield was not caused by a bullet. This means the shield might not be the exact one from the first contact story, but it is still a very important symbol for all Indigenous Australians. The discussion around the shield is part of a bigger movement to bring cultural items back to their original communities from museums around the world.

Return of Spears

Three of the spears were sent from Cambridge to the National Museum of Australia for an exhibition in 2020-2021. The La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council and La Perouse Aboriginal Community Alliance worked with the Cambridge museum to bring the spears home. In April 2021, it was announced that plans were made to return the spears to Country (their traditional land).

Notable People

- Biddy Giles (born around 1820, died around 1890s), also known as Biyarrung, was a Gweagal woman. She lived her whole life on Gweagal land. She was known for her deep knowledge of plants and the land, and she often guided white people. She spoke the Dharawal language very well.

- Rodney Kelly (born 1977) is a Gweagal activist. He is campaigning for the return of the shield held by the British Museum, as well as other Indigenous Australian items in museums across Europe and Australia.

See also

- Eora

- Repatriation (cultural heritage)

- Dharawal

- Australian Aboriginal artefacts

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |