HMS Birkenhead (1845) facts for kids

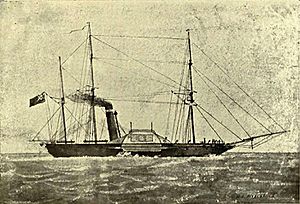

A contemporary picture of the ship

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Birkenhead |

| Namesake | Vulcan, Birkenhead |

| Builder | John Laird shipyard, Birkenhead |

| Launched | 30 December 1845 |

| Christened | HMS Vulcan |

| Renamed | HMS Birkenhead, 1845 |

| Reclassified | Troopship, 1851 |

| Fate | Wrecked 26 February 1852 at Danger Point near Gansbaai, Cape Colony |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Frigate, later troopship |

| Tonnage | 1400 bm |

| Displacement | 1918 tons as designed (2000 tons loaded) |

| Length | 210 ft (64 m) |

| Beam | 37 ft 6 in (11 m) |

| Draught | 15 ft 9 in (5 m) |

| Propulsion | Sail, plus 2× Forrester & Co 564 hp (421 kW) steam engines driving two 6 m (20 ft) diameter paddle wheels |

| Sail plan | Brig, later barquentine |

| Speed | 10 knots (19 km/h) as a troopship |

| Complement | 125 |

| Armament | 2 × 96-pounder pivot guns; 4× 68-pounder broadside guns |

| Notes | Iron hull; renamed HMS Birkenhead before commissioning |

HMS Birkenhead was one of the very first ships in the Royal Navy to be built with an iron hull. She was first designed as a fast steam frigate, but was later changed into a troopship to carry soldiers.

On February 26, 1852, while carrying troops and some civilians to Algoa Bay in South Africa, the Birkenhead hit a hidden rock. This happened near Danger Point, close to Gansbaai, about 87 miles (140 km) from Cape Town. There were not enough working lifeboats for everyone on board. The soldiers on the ship famously stood in neat lines, showing great discipline. This allowed the women and children to get into the lifeboats safely and escape the sinking ship.

Out of an estimated 643 people on board, only 193 survived. The brave actions of the soldiers led to the unofficial rule of "women and children first" when a ship is sinking. The phrase "Birkenhead drill" also became a way to describe showing courage even when things look hopeless.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Ship's Design and Early Life

The Birkenhead was built at John Laird's shipyard in Birkenhead, England. She was first named HMS Vulcan, but was quickly renamed Birkenhead after the town where she was built. The ship had two powerful steam engines that turned two large paddle wheels, each 6-metre (20 ft) wide. She also had two masts with sails, like a brig.

The ship was designed to be 210 feet (64 m) long and 37 feet 6 inches (11.43 m) wide. It was divided into eight watertight sections, plus four more in the engine room, making 12 watertight areas in total. This was meant to make the ship safer. The front of the ship had a large figurehead (a carved figure) of Vulcan, a god from Roman myths.

Launch and Changes

The Birkenhead was launched on December 30, 1845. Her first trip was to Plymouth in 1846, where she sailed at a good speed of 12 knots (22 km/h) to 13 knots (24 km/h).

The ship was not used much at first. In 1847, she helped rescue another famous iron ship, SS Great Britain, which had run aground in Ireland.

The Birkenhead was never used as a warship. While she was being built, two important things happened. First, the Royal Navy decided to switch from paddle wheels to more efficient propellers for their warships. Second, they found that iron hulls did not hold up well against cannon fire. Cannonballs made jagged holes that were hard to fix.

Because of these reasons, the Birkenhead was changed into a troopship in 1851. Extra decks were added to hold more people, and a third mast was put in to change her sail plan. Even though she wasn't a warship, she was much faster and more comfortable than the older wooden troopships. For example, she once traveled from the Cape to England in just 37 days.

The Final Voyage (1852)

In January 1852, the Birkenhead left Portsmouth, England. She was commanded by Captain Robert Salmond. The ship was carrying soldiers from ten different regiments, including the 2nd Regiment of Foot and the 74th Regiment of Foot. They were going to fight in the Eighth Xhosa War in the Cape Colony. On January 5, she picked up more soldiers, officers' wives, and families in Ireland.

On February 23, 1852, the Birkenhead stopped briefly at Simon's Town, near Cape Town. Most of the women and children got off there, along with some sick soldiers. The crew loaded nine cavalry horses, hay, and coal for the rest of the trip to Algoa Bay.

The ship left Simon's Bay at 6:00 PM on February 25, 1852. There were between 630 and 643 people on board. To go as fast as possible, Captain Salmond decided to stay close to the South African coast, usually within 3 miles (4.8 km) of the shore. The ship moved steadily at 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h). The sea was calm and the night was clear as she sailed east from False Bay.

Just before 2:00 AM on February 26, the Birkenhead was traveling at 8 knots (15 km/h). The sailor checking the water depth called out that it was 12 fathoms (22 m) deep. Before he could check again, the ship hit a hidden rock at 34°38′42″S 19°17′9″E / 34.64500°S 19.28583°E. This rock is near Danger Point, close to Gansbaai, Western Cape. It is hard to see in calm waters.

Captain Salmond quickly came on deck. He ordered the anchor to be dropped and the engines to go backward. But as the ship moved off the rock, water rushed into the huge hole. The ship hit the rock again, tearing open more parts of its bottom. The front sections and engine rooms quickly filled with water, and over 100 soldiers drowned in their sleeping areas.

The Sinking

The soldiers who survived gathered and waited for their officers' orders. Captain Salmond told the highest-ranking army officer, Colonel Seton, to send men to pump out the water. Sixty men went to the pumps, and another sixty were sent to help lower the lifeboats. The rest gathered on the back deck to try and lift the front of the ship.

The women and children were put into the ship's small boat, called a cutter. Two other large boats were supposed to hold 150 people each, but one immediately filled with water. The other could not be launched because it was poorly maintained. This left only three smaller boats available.

The surviving officers and men stood on deck. Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Foot took charge of all the soldiers. He told his officers how important it was to keep order and discipline. A survivor later said, "Almost everybody kept silent, indeed nothing was heard, but the kicking of the horses and the orders of Salmond, all given in a clear firm voice."

Ten minutes after the first hit, the ship struck the rock again under the engine room, tearing open its bottom even more. The ship instantly broke in two behind the main mast. The funnel fell into the sea, and the front part of the ship sank right away. The back part, crowded with men, floated for a few minutes before sinking too.

Just before the ship went down, Captain Salmond called out, "all those who can swim jump overboard, and make for the boats." However, Colonel Seton knew that if everyone rushed the lifeboats, they would tip over and endanger the women and children. So, he ordered the men to stay in place. Only three men tried to swim to the boats. The cavalry horses were set free and pushed into the sea, hoping they could swim to shore.

The soldiers did not move, even as the ship broke apart only 20 minutes after hitting the rock. Some soldiers managed to swim the 2 miles (3.2 km) to shore over the next 12 hours, often holding onto pieces of the wreck. But most drowned, died from the cold, or were killed by sharks.

One survivor, Lieutenant J.F. Girardot, wrote in a letter:

I remained on the wreck until she went down; the suction took me down some way, and a man got hold of my leg, but I managed to kick him off and came up and struck out for some pieces of wood that were on the water and started for land, about two miles off. I was in the water about five hours, as the shore was so rocky and the surf ran so high that a great many were lost trying to land. Nearly all those that took to the water without their clothes on were taken by sharks; hundreds of them were all round us, and I saw men taken by them close to me, but as I was dressed (having on a flannel shirt and trousers) they preferred the others. I was not in the least hurt, and am happy to say, kept my head clear; most of the officers lost their lives from losing their presence of mind and trying to take money with them, and from not throwing off their coats.

The next morning, a small sailing ship called the Lioness found one of the Birkenhead's boats. After rescuing the people in a second boat, the Lioness went to the disaster site. Arriving in the afternoon, she found 40 people still holding onto the ship's rigging. It was reported that out of about 643 people on board, only 193 were saved.

Aftermath and Legacy

A court hearing was held to investigate the accident. It took place on May 8, 1852, on board HMS Victory in Portsmouth. Many people were interested in the case. However, since none of the senior naval officers from the Birkenhead survived, no one was found to be at fault.

Captain Edward W. C. Wright, a surviving army officer, told the court:

The order and regularity that prevailed on board, from the moment the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I had thought could be effected by the best discipline; and it is the more to be wondered at seeing that most of the soldiers were but a short time in the service. Everyone did as he was directed and there was not a murmur or cry amongst them until the ship made her final plunge – all received their orders and carried them out as if they were embarking instead of going to the bottom – I never saw any embarkation conducted with so little noise or confusion.

In 1895, the Danger Point Lighthouse was built near Danger Point to warn ships about the dangerous reef. The lighthouse is about 18 metres (59 ft) tall. In 1936, a special plaque remembering the Birkenhead was placed at its base. A new memorial was put up nearby in 1995.

The bravery and discipline of the soldiers impressed Frederick William IV of Prussia so much that he ordered the story of the incident to be read to every regiment in his army. Queen Victoria ordered a monument to the Birkenhead to be built at the Chelsea Royal Hospital in London. In 1892, Thomas M. M. Hemy painted a famous picture of the sinking, called "The wreck of the Birkenhead."

Birkenhead Drill and Treasure

The "Birkenhead Drill"

The sinking of the Birkenhead is one of the earliest times where the idea of "women and children first" was used during a ship evacuation. This idea later became a standard rule for abandoning sinking ships, both in stories and in real life. The phrase "Birkenhead drill" came to mean showing courage in very difficult or hopeless situations. It was even mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's poem "Soldier an' Sailor Too" in 1893.

The Birkenhead Treasure Rumor

There was a rumor that the Birkenhead was carrying a large amount of gold coins, about £240,000 worth, weighing around three tons. People believed this gold was secretly stored in the ship's powder room. Many attempts have been made to find this gold.

In 1958, a famous diver from Cape Town found anchors and some brass parts, but no gold. From 1986 to 1988, a team carried out a big search. They only found a few gold coins, which seemed to belong to the passengers and crew, not a large military payroll.

Because of the treasure rumor and the wreck being in shallow water (30 metres (98 ft) deep), the site has been disturbed a lot. This is sad because the wreck is also a war grave. In 1989, the British and South African governments made an agreement to share any gold found from the wreck.

Places Named After the Birkenhead

Several places in the Canadian province of British Columbia were named in honor of the Birkenhead disaster. This was done by Hudson's Bay Company explorer Alexander Caulfield Anderson. He was a childhood friend and cousin of Lieutenant-Colonel Seton, who was on the Birkenhead.

Seton Lake and Anderson Lake were named after his cousin. Mount Birkenhead, the Birkenhead River, and Birkenhead Lake were all named after the ship itself.

Other Legacies

According to local stories, the Salmonsdam Nature Reserve in South Africa is named after Captain Robert Salmond. Also, people in the area still call Great White Sharks "Tommy Sharks." This name comes from the "Tommys" (British soldiers) who were taken by sharks in the water after the sinking.

See also

- Arniston, a ship that wrecked in 1815 on the same coast. It also involved soldiers from the 73rd Regiment of Foot.

- SS Tyndareus, a troopship that hit a mine in the same area in 1917. The troops were evacuated in an orderly way, similar to the Birkenhead, but no one died, and the ship was saved.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |