Heʻeia Fishpond facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Heʻeia Fishpond

|

|

A view of Heʻeia Fishpond on January 1, 2010, looking south-southeast from Heʻeia State Park.

|

|

| Location | Heʻeia, Hawaii |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Kāneʻohe, Hawaii |

| Area | 88 acres (36 ha) |

| Architectural style | Walled coastal pond (loko iʻa kuapā) |

| Restored | Restoration began 1988 |

| Restored by |

Mary Brooks

Paepae o Heʻeia |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000671 |

| Added to NRHP | January 17, 1973 |

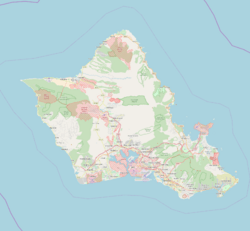

Heʻeia Fishpond (Hawaiian: Loko Iʻa O Heʻeia) is an old Hawaiian fishpond. It is found in Heʻeia on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. This special pond is a loko iʻa kuapā, which means it is a coastal pond surrounded by a wall. It is the only Hawaiian fishpond that has a wall (kuapā) all the way around it.

People built the fishpond between the early 1200s and early 1400s. A big flood in 1965 badly damaged it, and it was not used for many years. In 1973, it became a protected area and was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. This means it is a very important historical site. Since 1988, people have been working to fix it. They want to use it again for fishing, learning about Hawaiian culture, science, and education.

Contents

How Heʻeia Fishpond Works

Heʻeia Fishpond is a "kuapā-style" fishpond. This means it is a coastal pond with a wall. It covers about 88 acres (36 ha) in southern Kāneʻohe Bay on the coast of Oahu. It is the second largest of at least 20 fishponds that used to be along Kāneʻohe Bay.

What makes Heʻeia Fishpond special is its wall. The wall (kuapā) completely surrounds the pond. Other Hawaiian fishponds only have a wall that goes from one point on the shore to another. Heʻeia Fishpond's wall is built on a reef called Malaukaʻa. It might be the longest wall of any Hawaiian fishpond, stretching for about 1.3 miles (2.1 km).

The wall is 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) tall. It is made of two separate rock walls built with volcanic basalt rock (pohaku pele). The space between these two walls is filled with coral (loʻa) or dirt. The Hawaiians built the wall without using mortar. They used a special dry-stack technique called Uhau Humu Pohaku.

The fishpond is usually 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 m) deep. It is designed to mix fresh water (wai) from the land with salt water (kai) from Kāneʻohe Bay. This creates brackish water (wai hapa kai). This mix of water is perfect for fish to grow.

Heʻeia Stream flows along one side of the fishpond. Long ago, Hawaiians grew taro (kalo) in fields (lōʻiīkalo) that fed this stream. Flooding these taro fields helped keep the water clean. This reduced the amount of dirt that reached the fishpond.

The wall has seven working sluice gates (mākāhā). These gates control the water flow. Gates near the stream let fresh water in. Gates facing the bay control the tidal flow of salt water. The wall's design also keeps a base water level even when the tide is low. It also makes more water flow through the gates.

Each sluice gate has an inner and outer gate. When both gates are closed, fish inside a 10 to 15 feet (3.0 to 4.6 m) area are trapped. This makes it easy to catch fish for food. Some gates even have a small hut (hale) nearby. This hut gives shelter to people watching the gates.

Animals and Plants in the Pond

Hawaii does not have many natural lagoons like other places in the Pacific Ocean. But Heʻeia Fishpond, like other Hawaiian fishponds, creates a similar ocean environment. The brackish water and shallow depth are perfect for tiny plants called phytoplankton. They are also good for many kinds of edible seaweed and algae, which Hawaiians call limu.

By growing limu, the fishpond's caretaker (kiaʻi) can raise plant-eating fish without feeding them. It's like a rancher letting livestock graze on grass.

Many types of fish live in the pond, including:

- flathead grey mullet (ʻamaʻama)

- milkfish (awa)

- ringtail surgeonfish (pualu)

- eyestripe surgeonfish (palani)

- flagtail (āholehole)

- Pacific threadfin (moi)

- porcupinefish (kōkala)

- barracuda (kākū)

- small barred jack and island jack (pāpio)

- longjaw bonefish and shortjaw bonefish (ʻōʻio)

- whitesaddle goatfish (Parupeneus porphyreus or kūmū)

- yellowstripe goatfish (wekeʻaʻa)

The pond also has different kinds of crab (pāpaʻi), shrimp (ʻōpae), and eel (puhi).

Small fish swim into the fishpond through the sluice gates to eat the phytoplankton and limu. They stay because there is so much food. As they grow, they become too big to swim back out through the gates. They continue to grow until they are ready to be harvested. For mullet, this takes about three years. Fish are often drawn to the sluice gates during high tide. This makes it easy to trap and catch the fish that are ready, without harming the smaller ones.

History of the Fishpond

Heʻeia Fishpond was likely built between the early 1200s and early 1400s. The coral for its wall was found nearby. But the basalt rock had to be brought from at least 2 miles (3.2 km) away. Building the fishpond took about two to three years. It probably needed hundreds, or even thousands, of workers. Some say as many as 10,000 people helped build it.

Experts believe the fishpond was as important for feeding the local people as the taro fields. They think it supported a community of several thousand people in the Heʻeia area. There is even a story that King Kamehameha I helped take care of the fishpond.

In 1848, King Kamehameha III changed how land was owned in Hawaii. This was called the Great Māhele. Most of the land in Heʻeia, including the fishpond, went to High Chief Abner Kuhoʻoheiheipahu Pākī. He was the first recorded owner of Heʻeia Fishpond. When he passed away, his daughter Bernice Pauahi Bishop inherited the land. She later set up the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate to fund the Kamehameha Schools. The Kamehameha Schools still own the fishpond today.

Over the years, the fishpond likely changed due to storms, floods, and tsunamis. Starting around the 1860s, land use changed. Taro fields became rice paddies, then cattle pastures, and fields for sugar cane and pineapple. These new uses caused more erosion and dirt to build up in the fishpond. The taro patches were much better at keeping the water clean.

Old photos from 1880 to 1910 show the fishpond's wall was well-kept. The area also had smaller ponds and fields of different crops. In the 1920s, invasive mangrove trees were brought to Heʻeia. More buildings were put up near the fishpond from the 1930s to the 1960s. Still, the fishpond remained a famous landmark.

On May 2, 1965, the Keapuka Flood hit the area. It badly damaged over 1,000 feet (305 m) of the fishpond's wall, destroying over 200 feet (61 m) of it. After the flood, the fishpond was not used for over 20 years. Mangrove trees grew everywhere, and dirt built up inside the pond.

After the flood, some land developers wanted to build on the fishpond site. They managed to change the land's zoning from "agricultural" to "urban." This would allow them to fill in and build on the area. But the local community fought back. They got the fishpond placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. In 1974, the fishpond was rezoned as conservation land, protecting it from development.

Mary Brooks, an aquaculture expert, leased Heʻeia Fishpond in 1989. She and volunteers had already started fixing the damaged wall in 1988. The biggest break in the wall from the 1965 flood was an 80-foot (24 m) gap. Ocean currents had dug out the seabed up to 6 feet (1.8 m) below where the wall used to be. In 1992, Brooks and her volunteers built a temporary 253-foot (77 m) concrete wall.

Brooks tried raising fish in the pond. She had success with flathead grey mullet (ʻamaʻama), Pacific threadfin (moi), tilapia, and edible red seaweed called ogonori or "ogo." In the 1990s, Brooks created lessons on how to manage fishponds. In 2000, she worked with the University of Hawaiʻi to offer the first fishpond management class (Mālama Loko Iʻa). Her students then helped with the restoration work. This class led to the creation of Paepae o Heʻeia ("Threshold of Heʻeia") in 2001. This is a non-profit group dedicated to fixing and managing Heʻeia Fishpond.

Paepae o Heʻeia became the official caretakers of the fishpond in 2003. Their goal is to provide food and cultural knowledge to the local people. They also want the pond to be a place for science and education. In September 2006, Paepae o Heʻeia sold the first harvest of Pacific threadfin (moi) from the pond since the restoration began. In early 2007, they thought the restored fishpond could support 1,500 people.

Restoring the Fishpond

Paepae o Heʻeia has many programs to restore Heʻeia Fishpond. By 2007, they were holding community workdays twice a month. During these days, 40 to 100 volunteers helped with restoration under the group's guidance.

Removing Invasive Mangroves

Invasive mangroves, mostly red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), were brought to Heʻeia around 1922. After the 1965 flood, they grew wildly in Heʻeia Fishpond. They damaged the wall and caused a lot of dirt to build up. Mary Brooks started removing them in the late 1990s. Paepae o Heʻeia continued this work. By early 2007, 3,000 volunteers had removed 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) of mangroves. As of 2018, mangroves were cleared from 4,800 feet (1,463 m) of the 7,000-foot (2,134 m) wall. When possible, the mangrove wood is used as firewood or for building.

Repairing the Wall

The fishpond wall was damaged by the 1965 flood, mangrove roots, and eels. Some parts had only a few stones missing. Other parts were broken down to their foundation stones (niho). To fix the wall, volunteers first remove invasive plants like mangroves and other weeds. Then, they repair or rebuild the outer basalt parts of the wall. They fill the space between with coral. Between 2004 and 2007, volunteers repaired about 600 feet (180 m) of the wall. By early 2007, six of the wall's sluice gates (mākāhā) were working. By 2008, the temporary concrete wall built in 1992 needed to be replaced with a permanent repair. In December 2015, the largest hole in the wall was closed. A 164-foot (50 m) section of the wall destroyed in 1965 was not rebuilt as high as the original. This allows water to flow over it during high tide.

Removing Invasive Seaweed

Work to remove invasive seaweed from Heʻeia Fishpond began in 2004. This seaweed includes Kappaphycus, Acanthophora spicifera, and Gracilaria salicornia. By 2018, Paepae o Heʻeia had removed over 50 short tons (45 long tons; 45 tonnes) of it. This seaweed is rich in potassium. When possible, it is given to farmers to use as fertilizer. In 2019, Paepae o Heʻeia started working with the Heʻeia National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) and The Nature Conservancy. This partnership helps improve efforts to remove invasive seaweed.

Other Restoration Work

In 2020, the University of Hawaiʻi started a project. They installed special bioretention basins at storm drain outlets. These basins collect storm water from over 50 homes and streets before it enters Heʻeia Fishpond. The bioretention basins help clean the water by removing as many pollutants as possible. This improves the water quality in the fishpond.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |