Heinrich Brüning facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Heinrich Brüning

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Chancellor of Germany (Weimar Republic) |

|

| In office 30 March 1930 – 30 May 1932 |

|

| President | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Deputy | Hermann Dietrich |

| Preceded by | Hermann Müller |

| Succeeded by | Franz von Papen |

| Leader of the Centre Party | |

| In office 6 May 1933 – 5 July 1933 |

|

| Preceded by | Ludwig Kaas |

| Succeeded by | Party abolished |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 9 October 1931 – 30 May 1932 |

|

| Chancellor | Himself |

| Preceded by | Julius Curtius |

| Succeeded by | Konstantin von Neurath |

| Minister of Finance | |

| Acting 20 June 1930 – 26 June 1930 |

|

| Chancellor | Himself |

| Preceded by | Paul Moldenhauer |

| Succeeded by | Hermann Dietrich |

| Member of the Reichstag | |

| In office 27 May 1924 – 12 December 1933 |

|

| Constituency | Breslau (1924–1932) National list (1932–1933) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning

26 November 1885 Münster, Province of Westphalia, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 30 March 1970 (aged 84) Norwich, Vermont, U.S. |

| Resting place | Münster, Germany |

| Political party | Zentrum |

| Occupation | Academician Economist Activist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Imperial German Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1918 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | Infantry Regiment No. 30, Graf Werder |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards | Iron Cross, 1st Class Iron Cross, 2nd Class |

Heinrich Brüning (born November 26, 1885 – died March 30, 1970) was an important German politician and professor. He was a member of the Centre Party. He served as the Chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

Brüning was a smart political thinker and worked to help people. He became involved in politics in the 1920s. In 1924, he was elected to the Reichstag, which was the German parliament.

In 1930, he became chancellor just as the Great Depression hit Germany. His plans to save money and cut spending were not popular. Most of the Reichstag (parliament) disagreed with him. So, he used special powers from President Paul von Hindenburg to make laws. These were called emergency decrees. This meant he could make decisions without the parliament's full approval.

He stayed chancellor until May 1932. His plan to share land upset President Hindenburg. Hindenburg then stopped giving him special powers, and Brüning had to resign.

After Hitler came to power in 1933, Brüning left Germany in 1934. He moved to the United States. From 1937 to 1952, he taught at Harvard University. He returned to Germany in 1951 to teach at the University of Cologne. But he moved back to the United States in 1955 and lived there until he died.

Brüning is still a debated figure in German history. Some historians see him as the last person who tried to save the Weimar Republic. Others believe his actions, like using emergency powers, actually helped lead to its end.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Heinrich Brüning was born in Münster in Westphalia. His father died when Heinrich was only one year old. His older brother, Hermann Joseph, helped raise him. His family was Roman Catholic, but he was also influenced by the idea of duty from Lutheranism. This was because Münster had both Catholics and Protestants.

After finishing school, he first thought about becoming a lawyer. But then he studied Philosophy, History, German, and Political Science. He studied at universities in Strasbourg, the London School of Economics, and Bonn. In 1915, he earned his doctorate degree. His paper was about the financial and legal effects of the British railway system becoming government-owned.

Brüning joined the army as a volunteer in World War I from 1915 to 1918. He was accepted even though he had poor eyesight and was not very strong. He became a lieutenant and a company commander. He was recognized for his bravery and received the Iron Cross, both first and second class.

After the war ended in 1918, Brüning was elected to a soldiers' council. However, he did not support the German Revolution of 1918–1919. This revolution led to the creation of the Weimar Republic.

Starting a Political Career

Brüning did not like to talk about his personal life. But it is thought that his experiences in the war changed his plans. He decided not to continue his academic career. Instead, he wanted to help soldiers return to normal life. He helped them find jobs or continue their education.

He worked with a social reformer named Carl Sonnenschein. He also worked in a group that helped students with social issues. After six months, he joined the Prussian welfare department. There, he became a close helper to Adam Stegerwald, who was a minister. Stegerwald was also the leader of the Christian trade unions. In 1920, Stegerwald made Brüning the chief executive of these unions. Brüning held this job until 1930.

He was also the editor of a union newspaper called Der Deutsche (The German). In his writings, he supported a "social popular state" and "Christian democracy." These ideas were based on Christian principles for society.

In 1923, Brüning helped organize a peaceful protest called the "Ruhrkampf". This was against the occupation of the Ruhr region.

Brüning joined the Centre Party. In 1924, he was elected to the Reichstag (parliament) to represent Breslau. In the Reichstag, he quickly became known as an expert on money matters. He helped pass a law, sometimes called the Brüning Law. This law limited how much income tax workers had to pay.

From 1928 to 1930, he was a member of the Landtag of Prussia, which was the Prussian state parliament. In 1929, he became the leader of the Centre Party group in the Reichstag. His party agreed to the Young Plan, which was about Germany's war payments. But they said it had to be paid for by raising taxes and cutting the budget. This caught the attention of President Paul von Hindenburg.

Becoming Chancellor of Germany

In March 1930, the government led by Social Democrat Hermann Müller fell apart. President Hindenburg then chose Brüning to be the chancellor on March 29, 1930. Brüning was good with money and economics. He also cared about social issues. His service as a soldier in the war made him acceptable to Hindenburg.

Brüning's government faced the huge challenge of the Great Depression. Also, the 1929 Young Plan had reduced the money Germany owed for war reparations. But paying the rest still meant the country had to save a lot of money. Brüning told his friends that his main goal was to free Germany from these payments and foreign debts. This would mean very strict money policies and cutting wages.

The Reichstag (parliament) rejected Brüning's plans within a month. President Hindenburg thought this showed that parliament was failing. With Brüning's agreement, Hindenburg called for new elections. In the meantime, Brüning's plans were put into action using presidential emergency decrees. These were special orders under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution.

These strict money policies helped Germany's trade, but they also made unemployment and poverty worse. As more people lost their jobs, Brüning's cuts to wages and public help, along with rising prices and taxes, made life harder for many. People started to say, "Brüning verordnet Not!" which meant "Brüning decrees hardship!" He became very unpopular.

Hindenburg wanted the government to be supported by right-wing parties. But the right-wing German National People's Party (DNVP) refused to support Brüning. So, Brüning had to rely on his own Centre Party, which was the only party that fully supported him. He also needed the Social Democrats to tolerate his government.

In the December 1930 election, the main parties lost many seats. The Communists and the National Socialists (Nazis) gained a lot of power. This meant Brüning had no hope of forming a majority in the Reichstag. So, he kept governing using emergency decrees. He called this an "authoritative democracy," meaning the president and parliament worked together in a strong way.

Brüning had mixed feelings about democracy. Soon after he became chancellor, he greatly limited freedom of the press. It's estimated that 100 newspaper editions were banned every month.

Brüning's tough economic policies made the Social Democrats less willing to support his government. Meanwhile, other ministers in his cabinet wanted to include more right-wing parties. President Hindenburg, influenced by his close advisors and military chief Kurt von Schleicher, also wanted this. He insisted that Brüning change his cabinet.

The president's wishes also made it harder for the government to fight against extremist parties. These parties had their own armed groups. Brüning and Hindenburg agreed that the Communists and Nazis were too violent and extreme to be in government. Brüning believed his government was strong enough to guide Germany through the crisis without the Nazis' help.

However, he did talk with Hitler about the Nazis supporting his government. But Brüning did not want to give the Nazis any real power. Because of this, the talks failed. As street violence grew in April 1932, Brüning banned both the Communist "Rotfrontkämpferbund" and the Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA). This ban made right-wing groups unhappy and further weakened Hindenburg's support for Brüning.

Brüning worried about how to stop the growing power of the Nazis. He knew Hindenburg might not live through another full term as president. If Hindenburg died, Hitler would be a strong candidate to take his place.

In his writings published after his death, Brüning claimed he had a last-ditch plan to stop Hitler. He wanted to bring back the old German monarchy. He planned to convince the Reichstag to cancel the 1932 German presidential election and extend Hindenburg's term. Then, he would have the Reichstag declare a monarchy, with Hindenburg as a temporary ruler. After Hindenburg's death, one of Crown Prince Wilhelm's sons would become king. This new monarchy would be like the British one, where the parliament held the real power.

Brüning said he got support for this plan from most major parties, except the Nationalists, Communists, and Nazis. This meant the plan likely would have passed. However, the plan failed because Hindenburg, who was an old-fashioned monarchist, refused to support it unless Kaiser Wilhelm II (the former emperor) was allowed to return from exile. When Brüning tried to explain that neither the Social Democrats nor other countries would accept the return of the old Kaiser, Hindenburg became angry and dismissed him.

Foreign Policy Goals

Even with his strict money policies, Brüning pursued a strong, nationalist foreign policy. He wanted to build two battlecruisers for the German navy. He also wanted to increase Germany's influence in central and eastern Europe. He signed trade agreements with Hungary and Romania. Brüning tried to reduce the amount of money Germany had to pay in war reparations. He also wanted Germany to be treated equally when it came to rearming its military. In 1930, he responded to a French idea for a "United States of Europe" by demanding full equality for Germany. He refused offers of French money to help Germany's struggling economy.

Brüning's nationalist foreign policy made it harder to get foreign investments in Germany. In 1931, plans for a customs union between Germany and Austria were stopped by France. Brüning reacted by demanding that the Treaty of Versailles be cancelled. He also announced that Germany would stop paying reparations. This caused a financial panic, which led to banking crises in Germany.

US President Herbert Hoover tried to prevent more problems. He negotiated the Hoover Moratorium, which postponed reparations and other war debt payments. France did not approve and delayed agreeing to it. This delay caused a bank run that led to the collapse of a major German bank. The German central bank had to close the financial system and stop using the Reichsmark based on the gold standard. It also controlled imports and foreign money. Brüning's actions caused the Bank of England to stop linking the pound sterling to gold. This made the Great Depression much worse around the world. In the summer of 1932, after Brüning resigned, his successors benefited from his policies. At the Lausanne conference, war reparations were reduced to a final payment of 3 billion marks.

Talks about rearming Germany failed at the 1932 Geneva Conference just before Brüning resigned. But in December, the "Five powers agreement" accepted Germany's right to military equality.

Hindenburg's Re-election and Brüning's Resignation

At first, President Hindenburg did not want to run for re-election. But he later changed his mind. In the 1932 presidential election, Brüning strongly supported Hindenburg. Almost all German left and center parties also supported him. Brüning called Hindenburg a "respected historical figure" and "the protector of the constitution." After two rounds of voting, Hindenburg was re-elected. He won by a large amount over his main opponent, Hitler. However, Hindenburg felt it was embarrassing to be elected with votes from "Reds" (Social Democrats) and "Catholes" (the mostly Catholic Centre Party). He knew they saw him as the lesser of two evils. To make up for this "shame," he moved further to the right in his politics. His declining health also made his close advisors more powerful.

Brüning slowly lost Hindenburg's support. The ban on the Nazi SA (their armed group) on April 13, 1932, made the conflict worse. It caused bad feelings between Hindenburg and his trusted friend Kurt von Schleicher. At the same time, wealthy Prussian landowners, led by Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau, strongly attacked Brüning. They opposed Brüning's plan to give land to unemployed workers as part of a program called Eastern Aid. They called him an "Agro-bolshevik" to Hindenburg.

The president, who owned a heavily indebted estate himself, refused to sign any more emergency decrees. Because of this, Brüning and his government resigned on May 30, 1932. Hindenburg dismissed him in a short and undignified ceremony. Brüning refused to tell the public about the president's disloyal behavior. He thought it was improper and still saw Hindenburg as the "last protector" of the German people.

After Being Chancellor

After Brüning resigned as chancellor, the Centre Party chairman, Ludwig Kaas, asked Brüning to take his place. But Brüning refused and asked Kaas to stay. Brüning supported his party's strong opposition to the new chancellor, Franz von Papen. He also supported trying to make the Reichstag work again by cooperating with the Nazis. He even talked with Gregor Strasser, a Nazi leader.

After Hitler became chancellor on January 30, 1933, Brüning strongly campaigned against the new government in the March 1933 elections. Later that month, he strongly opposed Hitler's Enabling Act. He called it "the most monstrous resolution ever demanded of a parliament." But Hitler promised that the Centre Party would not be banned. So, Brüning followed his party's decision and voted for the bill. Since the Communist members were already banned from the Reichstag, only the Social Democrats voted against the act.

Kaas, who was a priest, moved to Rome in 1933 to help the Vatican negotiate with Germany. So, in May 1933, he resigned as party chairman. Brüning was then elected chairman on May 6. The party tried to adapt to the new rules after the Enabling Act. They adopted a weaker version of the leadership principle. Pro-Centre newspapers said that the party's members would fully follow Brüning. But this only kept the party alive for a few more months. Important members were often arrested and beaten. Civil servants who supported the Centre Party were fired. Nazi officials demanded that the party either close down or be banned. Brüning had no choice but to dissolve the Centre Party on July 5.

Life in Exile and Later Years

In 1934, friends warned Brüning about the upcoming Night of the Long Knives, a violent purge by the Nazis. On June 3, 27 days before the purge, he fled Germany through the Netherlands.

After staying in Switzerland and the United Kingdom, he went to the United States in 1935. In 1937, he became a visiting professor at Harvard University. From 1939 to 1952, he was a professor of government there. He became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1938. He warned the American public about Hitler's plans for war. Later, he warned about Soviet aggression and expansion plans. But in both cases, his advice was mostly ignored.

In 1951, he returned to Germany. He settled in Cologne in West Germany. He taught as a professor of political science at the University of Cologne until he retired in 1953. He was not happy with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer's policies. So, he returned to the U.S. in 1955. There, he worked on his book, Memoirs 1918–1934, which was edited by his assistant, Claire Nix.

Because the book had very controversial content, it was not published until after his death in 1970. Some parts of his memoirs are considered unreliable. They are not always based on historical records and seem to be his way of explaining his political choices during the Weimar Republic.

Brüning died on March 30, 1970, in Norwich, Vermont. He was buried in his hometown of Münster, Germany.

Images for kids

-

Chancellor Brüning (left) and Foreign Minister Julius Curtius (right) saying good-bye to British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald at Berlin Tempelhof Airport, July 1931

-

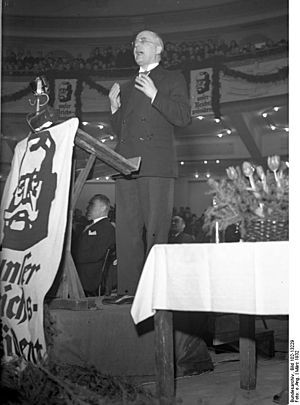

Chancellor Brüning campaigning for Hindenburg's re-election, Berlin Sportpalast, March 1932

Error: no page names specified (help). In Spanish: Heinrich Brüning para niños

In Spanish: Heinrich Brüning para niños