History of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan facts for kids

This article is about the history of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan from 1899 to 1955. This was a time when Sudan was ruled jointly by the United Kingdom (Britain) and Egypt.

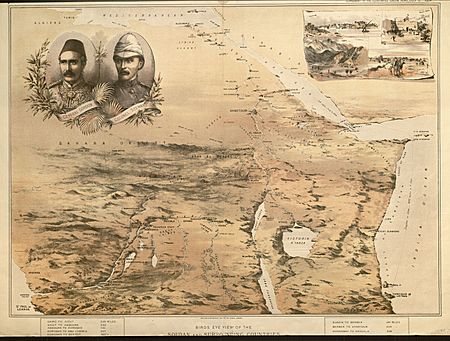

In January 1899, Britain and Egypt made an agreement. It said that Egypt would rule Sudan again, but it would be a "condominium." This means Britain and Egypt would share control. The area south of the 22nd parallel was named Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Even though Egypt owed Britain for helping to take back Sudan, the agreement wasn't clear about how Britain and Egypt would share power.

The agreement stated that one person, called the Governor-General of Sudan, would be in charge. The Governor-General was chosen by Egypt's leader (the Khedive) based on Britain's suggestion. This person could only be removed with Britain's agreement.

The British Governor-General was usually a military officer. They reported to the British Foreign Office in Cairo, Egypt. But in reality, they had a lot of power and ran Sudan from Khartoum almost like a British colony. Sir Reginald Wingate became Governor-General in 1899, after Kitchener.

In each province, British governors (called mudirs) had help from inspectors and district commissioners. At first, most of these administrators were British Army officers. But in 1901, British civilians started coming to Sudan to work in the Sudan Political Service. Egyptians filled middle-level jobs, and Sudanese people slowly got lower-level jobs.

Contents

Joint Rule in Sudan (1899-1955)

In the early years of joint rule, the Governor-General and provincial governors had a lot of freedom. But after 1910, an executive council was created. This council had to approve all new laws and budget plans.

The Governor-General led this council. It included important British officials like the inspector-general and various secretaries. From 1944 to 1948, there was also an Advisory Council for Northern Sudan. This council gave advice and had 18 members from local councils, 10 chosen by the Governor-General, and 2 honorary members. The executive council kept its law-making power until 1948.

Keeping Order and Laws

After bringing peace back to Sudan, the British worked on creating a modern government. They made new laws for crimes and legal procedures, similar to those in British India. They also set up rules for land ownership and settled land disputes.

Taxes on land were the main way the government collected money. The amount depended on how the land was watered, the number of date palm trees, and the size of animal herds. For the first time in Sudan's history, the tax rates were fixed.

A law in 1902 kept civil law and sharia (Islamic law) separate, as they had been under the Ottomans. But it also set up rules for how sharia courts would work. These courts were independent and led by a chief qadi (religious judge) chosen by the Governor-General. The religious judges were always Egyptian.

There wasn't much resistance to the joint rule. Most problems were small fights between tribes or banditry. There were a few small revolts by followers of the Mahdi in 1900, 1902–3, 1904, and 1908. In 1916, a man named Abd Allah as Suhayni claimed to be the Prophet Isa and started a religious war, but it failed.

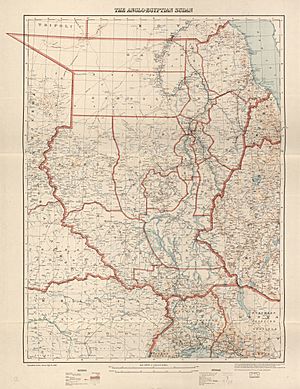

Setting Sudan's Borders

A bigger challenge was that Sudan's borders were not clearly defined. In 1902, a treaty with Ethiopia set the southeastern border. Seven years later, a treaty with Belgium decided the status of the Lado Enclave in the south, setting a border with the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

The western border was harder to fix. Darfur was the only province that had been under Egyptian control but wasn't quickly brought back under the joint rule. When the Mahdist state fell apart, Sultan Ali Dinar took back control of Darfur. The British allowed this, as long as he paid yearly tribute to the Khedive of Egypt.

When World War I began, Ali Dinar supported the Ottoman Empire and called for a religious war against the Allies. Britain, which had taken control of Egypt in 1914, sent a small army against Ali Dinar. He died in the fighting. In 1916, the British added Darfur to Sudan and ended the Fur sultanate.

Developing Sudan's Economy

During the joint rule, economic growth mostly happened in the settled areas along the Nile River. In the first 20 years, the British built telegraph and rail lines to connect important places in northern Sudan. But remote areas did not get these services. Port Sudan opened in 1906, becoming the country's main seaport instead of Sawakin.

In 1911, the Sudanese government and a private company started the Gezira Scheme. This project aimed to grow high-quality cotton for Britain's textile factories. A large dam near Sennar, finished in 1925, helped water a much bigger area in Al Jazirah. Cotton was sent by train from Sennar to Port Sudan for shipping. The Gezira Scheme made cotton the most important part of Sudan's economy and made the Al Jazirah region the most populated area.

Egypt's Freedom and Sudan's Future

In 1922, Britain ended its control over Egypt and approved Egypt's independence. However, Egypt's new constitution in 1923 did not claim Sudan as part of Egypt. Later talks in London between Britain and the new Egyptian government failed because of the "Sudan question."

Because the talks failed, nationalists protested in Egypt and Sudan. A small group in Sudan, led by Ali Abd al Latif, wanted to unite with Egypt. In November 1924, Sir Lee Stack, the Governor-General of Sudan, was killed in Cairo. Britain ordered all Egyptian troops and government workers to leave Sudan. In 1925, Khartoum formed the 4,500-man Sudan Defence Force (SDF) with Sudanese officers to replace the Egyptian soldiers.

Indirect Rule in Sudan

Sudan was fairly calm in the late 1920s and 1930s. During this time, the British colonial government preferred "indirect rule." This meant they governed through local leaders instead of directly.

In northern Sudan, these leaders were the shaykhs (of villages, tribes, and districts). In the south, they were tribal chiefs. The British first gave shaykhs the power to settle local disagreements. Then, they slowly allowed them to run local governments, supervised by British district commissioners. How much power these leaders had varied a lot.

Many educated Sudanese leaders in Khartoum did not like indirect rule. They believed it stopped the country from uniting and made tribal differences worse in the north. In the south, they felt it kept society less developed and stopped Arab influence. Indirect rule also meant the government was less centralized. This worried the educated elite, who wanted to take over from the British.

Some nationalist groups and the Khatmiyyah religious group were against indirect rule. But the Ansar (followers of the Mahdi) supported it, as many of them held local leadership positions.

Britain's Policy for Southern Sudan

From the start of the joint rule, the British wanted to modernize Sudan. They wanted to bring European technology and change old ways of governing to be more like British traditions.

The remote and undeveloped southern provinces—Equatoria, Bahr al Ghazal, and Upper Nile—got little attention until after World War I. The British mostly tried to stop tribal wars and the slave trade there. They said the south wasn't ready for the modern world. To let the south develop on its own, the British closed the region to outsiders. This made the south very isolated.

A few Arab merchants controlled the small amount of trade, and Arab officials ran the laws. Christian missionaries, who ran schools and medical clinics, offered some social services in southern Sudan.

The first Christian missionaries were the Verona Fathers, a Roman Catholic group. Other groups included Presbyterians from the United States and the Anglican Church Missionary Society. They didn't compete because they worked in different areas. The government eventually helped fund the mission schools that educated southerners. Many northerners saw these graduates as tools of British rule. The few southerners who got higher education went to schools in British East Africa (now Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania) instead of Khartoum. This made the division between north and south even stronger.

"Closed-Door" Rules

British officials treated the three southern provinces as a separate region. As the colonial government became stronger in the south in the 1920s, it separated the south from the rest of Sudan for most purposes.

"Closed door" rules were put in place. These rules stopped northern Sudanese from entering or working in the south. This policy made the south develop separately. Also, the British slowly replaced Arab administrators and removed Arab merchants. This cut off the south's last economic ties with the north. The colonial government also discouraged the spread of Islam, Arab customs, and Arab clothing. At the same time, the British tried to bring back African customs and tribal life that had been disrupted by the slave trade. In 1930, a rule stated that black people in the southern provinces were different from northern Muslims. It said the region should be prepared to join British East Africa eventually.

Even though the south could have been a rich farming area, its economy suffered because it was isolated. There were also constant disagreements between British officials in the north and south. Northern officials resisted suggestions to use northern resources to help the south's economy grow. Personal conflicts between officials in the two parts of the Sudan Political Service also slowed the south's growth.

Officials who worked in the southern provinces were often military officers with experience in Africa. They usually didn't trust Arab influence and wanted to keep the south under British control. In contrast, officials in the northern provinces were often experts in Arab culture, often from diplomatic services. While northern governors met regularly with the Governor-General in Khartoum, the three southern governors met to plan activities with the governors of the British East African colonies.

Sudanese Nationalism Grows

Sudanese nationalism, which grew after World War I, was mostly an Arab and Muslim movement. It was strongest in the northern provinces. Nationalists did not like indirect rule. They wanted a strong central government in Khartoum that would control both northern and southern Sudan. Nationalists also saw Britain's southern policy as dividing Sudan artificially. They believed it stopped Sudan from uniting under an Arab and Islamic ruling class.

Interestingly, Sudan's first modern nationalist movement was led by a non-Arab. In 1921, Ali Abd al Latif, a Muslim Dinka and former army officer, started the United Tribes Society. This group wanted an independent Sudan where tribal and religious leaders would share power. Three years later, Ali Abd al Latif's movement, now called the White Flag League, organized protests in Khartoum. These protests happened after Stack's assassination. Ali Abd al Latif was arrested and sent away to Egypt. This led to a mutiny by a Sudanese army battalion, which was put down. This temporarily weakened the nationalist movement.

In the 1930s, nationalism grew again in Sudan. Educated Sudanese wanted to limit the Governor-General's power. They also wanted Sudanese people to be part of the council's discussions. However, any change in government needed a change in the joint rule agreement. Neither Britain nor Egypt would agree to this. The British saw their role as protecting the Sudanese from Egyptian control. Nationalists worried that the disagreements between Britain and Egypt might lead to northern Sudan joining Egypt and southern Sudan joining Uganda and Kenya.

Even though Britain and Egypt settled most of their differences in the 1936 Treaty of Alliance, they still couldn't agree on Sudan's future. The treaty set a timeline for British troops to leave Egypt.

Nationalists and religious leaders were divided on whether Sudan should become independent or unite with Egypt. The Mahdi's son, Abd ar Rahman al Mahdi, spoke for independence. He was against Ali al Mirghani, the Khatmiyyah leader, who wanted to unite with Egypt. Groups supporting each leader formed rival parts of the nationalist movement. Later, radical nationalists and the Khatmiyyah created the Ashigga, which was later renamed the National Unionist Party (NUP). This party wanted Sudan to unite with Egypt. The moderate nationalists wanted Sudan to be independent in cooperation with Britain. They, along with the Ansar, formed the Umma Party.

The Path to Independence

As World War II got closer, the Sudan Defence Force (SDF) was given the job of guarding Sudan's border with Italian East Africa (now Ethiopia and Eritrea). In the summer of 1940, Italian forces invaded Sudan at several points. They captured the railway hub at Kassala and other border villages. However, while Port Sudan was attacked by Eritrean forces in August 1940, the SDF stopped the Italians from reaching the Red Sea port city.

In January 1941, the SDF, which had grown to about 20,000 troops, took back Kassala. They also helped in the Allied attack that defeated the Italians in Eritrea and freed Ethiopia by the end of the year. Some Sudanese units later helped the Eighth Army in its successful North African Campaign.

In the years right after the war, the joint government made important changes. In 1942, the Graduates' General Conference, a nationalist group of educated Sudanese, gave the government a list of demands. They asked for a promise of self-determination after the war. They also wanted the "closed door" rules to end, a single school system for north and south, and more Sudanese people in government jobs. The Governor-General refused the demands but agreed to change indirect rule into a modern local government system. Sir Douglas Newbold, a governor in the 1930s, suggested creating a parliament and uniting the north and south administratively. In 1948, despite Egypt's objections, Britain allowed a partially elected Legislative Assembly to replace the advisory executive council. This assembly represented both regions. It had its own executive council with five British and seven Sudanese members. Local elected governments slowly took over from British local commissioners, starting with El Obeid. By 1952, Sudan had 56 local self-governing authorities.

The pro-Egyptian NUP boycotted the 1948 Legislative Assembly elections. Because of this, groups that wanted independence controlled the Legislative Assembly. In 1952, leaders of the Umma-dominated legislature negotiated the Self-Determination Agreement with Britain. The lawmakers then created a constitution. It set up a prime minister and a council of ministers who would answer to a two-house parliament. The new Sudanese government would be in charge of everything except military and foreign affairs, which stayed with the British Governor-General. Cairo, which wanted Egypt to be recognized as the ruler of Sudan, rejected the joint rule agreement in protest. It declared its king, Faruk, as king of Sudan.

After taking power in Egypt and overthrowing the Faruk monarchy in late 1952, Colonel Muhammad Naguib broke the stalemate over Egyptian control of Sudan. Cairo had previously linked talks about Sudan's status to an agreement on British troops leaving the Suez Canal. Naguib separated the two issues and accepted that the Sudanese had the right to decide their own future. In February 1953, London and Cairo signed an agreement. It allowed for a three-year period to transition from joint rule to self-government. During this time, British troops would leave Sudan. At the end of this period, the Sudanese would vote on their future in a plebiscite (a direct vote by all eligible voters) supervised by international observers. Naguib's decision seemed right when parliamentary elections in late 1952 gave a majority to the pro-Egyptian NUP, which had called for eventual union with Egypt. In January 1954, a new government was formed under NUP leader Ismail al-Azhari.

Southern Sudan and Unity

During World War II, some British colonial officers wondered if the southern provinces could survive economically and politically as separate from northern Sudan. Britain also became more aware of Arab criticism of its southern policy. In 1946, the Sudan Administrative Conference decided that Sudan should be governed as one country. The conference also agreed to allow northern administrators back into southern jobs. They ended the trade restrictions from the "closed door" rules and let southerners seek jobs in the north. Khartoum also removed the ban on Muslims trying to spread their faith in the south and made Arabic the official language of administration in the south.

Some British officials in southern Sudan reacted to the Sudan Administrative Conference by saying that northern groups had influenced the conference. They felt that no one at the conference had spoken up for keeping the separate development policy. These British officers argued that northern control of the south would lead to a southern rebellion against the government. So, Khartoum held a conference at Juba to calm the fears of southern leaders and British officials in the south. They promised that a government after independence would protect southern political and cultural rights.

Despite these promises, more and more southerners worried that northerners would overpower them. They especially disliked Arabic becoming the official language. This meant that most of the few educated English-speaking southerners could not get public service jobs. They also felt threatened when trusted British district commissioners were replaced with northerners who seemed unsympathetic. After the government replaced hundreds of colonial officials with Sudanese, only four of whom were southerners, the southern elite lost hope for a peaceful, united, independent Sudan.

The anger of southerners toward the northern Arab majority erupted violently in August 1955. Southern army units mutinied to protest being transferred to garrisons under northern officers. The rebellious troops killed hundreds of northerners, including government officials, army officers, and merchants. The government quickly stopped the revolt and eventually executed seventy southerners for rebellion. But this harsh reaction did not calm the south. Some of the mutineers escaped to remote areas and organized resistance against the Arab-dominated government of Sudan.

See also

- History of Sudan

- Sudan–United Kingdom relations

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |