History of Bulgaria (1878–1946) facts for kids

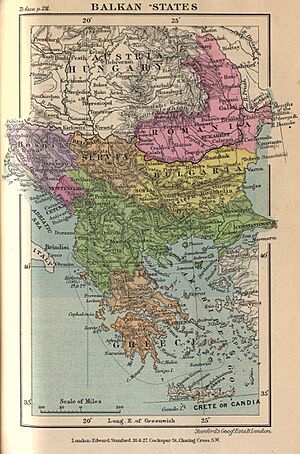

After a big war called the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 created a new, self-governing country called the Principality of Bulgaria. Even though it was still officially part of the Ottoman Empire, it acted like an independent state. In 1879, Alexander of Battenberg became its first prince. Later, in 1885, Prince Alexander also took control of Eastern Rumelia, another Ottoman area, joining it with Bulgaria. After Prince Alexander left in 1886, the Bulgarians chose Ferdinand I as their new prince in 1887. Bulgaria finally became completely independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1908.

In the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), Bulgaria first teamed up with Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro to fight the Ottoman Empire. Together, they won a lot of land. But Bulgaria wasn't happy with how the land was divided after the first war. So, it soon went to war against its former friends, Serbia and Greece, and ended up losing some of the land it had gained. During World War I (1914–1918), Bulgaria fought (1915–1918) alongside Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. After they lost, the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (1919) made Bulgaria lose even more land. The country faced many social problems and political troubles during the years between the two World Wars. In World War II (1939–1945), Bulgaria again joined Germany in March 1941. Even though Bulgaria tried to leave the war in 1944 as the Soviet Union's army got closer, the Red Army invaded in September 1944. A communist government then took power (1944–1946) and created the People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1990).

Contents

Bulgaria's Early Years (1878–1912)

After the Russo-Turkish War, a plan called the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878) suggested creating a large, self-governing Bulgarian state. This state would include areas like Moesia, Thrace, and Macedonia. But other big European countries, especially Great Britain and Austria-Hungary, were worried. They feared that a large Bulgaria would become too close to Russia and give Russia too much power in the Balkans. Great Britain was concerned about its trade routes to the Suez Canal and India. Austria-Hungary worried that a big independent Slavic country would encourage its own Slavic people to seek independence.

Because of these concerns, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli helped create a new agreement called the Treaty of Berlin (1878). This treaty made the new Bulgarian state much smaller. It created an independent Principality of Bulgaria between the Danube River and the Stara Planina mountains, with its capital in Veliko Tarnovo, and including Sofia. This new state was still officially under Ottoman rule, but it would be led by a prince chosen by Bulgarian leaders. The European powers insisted the prince could not be Russian. However, as a compromise, Prince Alexander of Battenberg, who was a nephew of Russian Tsar Alexander II, was chosen. The treaty also created another self-governing Ottoman area called Eastern Rumelia south of the Stara Planina mountains, while Macedonia went back under the Sultan's control.

Joining with Eastern Rumelia

The Bulgarians adopted a very modern and democratic constitution. Power soon went to the Liberal Party, led by Stefan Stambolov. Prince Alexander was more traditional, and at first, he didn't agree with Stambolov's ideas. But by 1885, he started to support his new country more and changed his mind, backing the Liberals. He also supported the joining of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. This happened through a sudden takeover in Plovdiv in September 1885. The big European powers didn't get involved because they were busy with their own power struggles.

Soon after, Serbia declared war on Bulgaria. Serbia hoped to grab some land while Bulgaria was busy. But the Bulgarians defeated them at Slivnitsa and then pushed deep into Serbian territory. However, Bulgaria had to stop its advance when Austria-Hungary threatened to help Serbia. The joining of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia was accepted by the European powers as a "personal union," meaning they shared the same ruler.

Prince Ferdinand's Rule

These events made Prince Alexander very popular in Bulgaria. But Russia became unhappy with his liberal ideas. In August 1886, Russia helped start a takeover that forced Alexander to leave the country. Stambolov, however, quickly acted, and those involved in the takeover had to flee. Stambolov tried to bring Alexander back, but strong opposition from Russia forced the prince to leave again.

In July 1887, the Bulgarians chose Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha as their new Prince. Ferdinand was favored by Austria, and Russia refused to recognize him, even though he was friends with Tsar Alexander III. Ferdinand worked with Stambolov at first, but their relationship worsened by 1894. Stambolov resigned and was killed in July 1895. Ferdinand then decided to improve relations with Russia, which meant returning to more traditional policies.

Many Bulgarians still lived under Ottoman rule, especially in Macedonia. To make things more complicated, Serbia and Greece also claimed parts of Macedonia. This led to the Balkan Wars, a struggle for control of these areas that continued through World War I. In 1903, there was a Bulgarian uprising in Ottoman Macedonia, and war seemed likely. In 1908, Ferdinand used the disagreements between the big European powers to declare Bulgaria a fully independent kingdom, with himself as Tsar. He did this on October 5 (though celebrated on September 22) in the St Forty Martyrs Church in Veliko Tarnovo.

The Ilinden Uprising

The main problem for Bulgaria's foreign policy before World War I was the future of Macedonia and Eastern Thrace. In the late 1800s, the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) was formed. This group started preparing for an armed uprising in the regions still controlled by the Ottoman Turks. With support from Bulgaria, IMARO set up a network of groups in Macedonia and Thrace.

On August 2, 1903, a large armed uprising, known as the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, began in Macedonia and Thrace. Its goal was to free these regions or at least get the attention of the Great Powers so they would push for better living conditions and reforms for the people there. After three months of fierce fighting, the Ottoman army crushed the uprising, using much cruelty against the people.

The Balkan Wars

In 1911, the Prime Minister, Ivan Evstratiev Geshov, worked to form an alliance with Greece and Serbia. These three allies agreed to put aside their disagreements and plan a joint attack on the Ottomans.

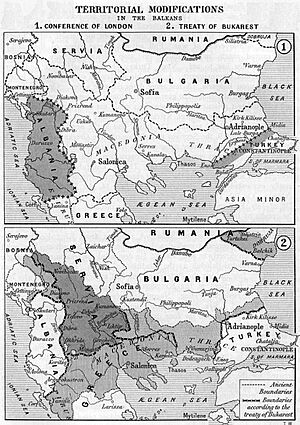

In February 1912, Bulgaria and Serbia signed a secret treaty. In May 1912, a similar treaty was signed with Greece. Montenegro also joined this group, known as the Balkan League. The treaties planned to divide Macedonia and Thrace among the allies, though the exact borders were left unclear, which was risky. When the Ottomans refused to make reforms in the disputed areas, the First Balkan War began in October 1912.

The allies had amazing success. The Bulgarian army defeated the Ottoman forces many times and advanced close to Istanbul. Meanwhile, the Serbs and Greeks took control of Macedonia. The Ottomans asked for peace in December. Talks broke down, and fighting started again in February 1913. The Ottomans lost Adrianople to a combined Bulgarian-Serbian force. A second ceasefire followed in March. The Ottomans lost all their European lands west of a line not far from Istanbul. Bulgaria gained most of Thrace, including Adrianople and the Aegean port of Alexandroupoli. Bulgaria also gained a part of Macedonia, north and east of Thessaloniki (which went to Greece), but only small areas along its western borders.

Bulgaria suffered the most casualties of all the allies. Because of this, it felt it deserved the largest share of the land. However, the Serbs disagreed. They refused to leave the territory they had taken in northern Macedonia (which is roughly modern North Macedonia). They argued that the Bulgarian army had not achieved its goals at Adrianople without Serbian help, and that the pre-war agreements on dividing Macedonia needed to be changed. Some people in Bulgaria wanted to go to war with Serbia and Greece over this issue.

In June 1913, Serbia and Greece formed a new alliance against Bulgaria. The Serbian Prime Minister, Nikola Pašić, told Greece it could have Thrace if Greece helped Serbia keep Bulgaria out of the Serbian part of Macedonia. The Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos agreed. Seeing this as a violation of the earlier agreements, and secretly encouraged by Germany and Austria-Hungary, Tsar Ferdinand declared war on Serbia and Greece. The Bulgarian army attacked on June 29. The Serbian and Greek forces initially retreated on the western border, but they soon gained the upper hand and forced Bulgaria to retreat. The fighting was very harsh, with many casualties, especially during the important Battle of Bregalnica. Soon, Romania entered the war and attacked Bulgaria from the north. The Ottoman Empire also attacked from the southeast. The war was now clearly lost for Bulgaria. It had to give up most of its claims in Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, while the Ottomans retook Adrianople. Romania took control of southern Dobruja.

War and Social Changes

World War I (1914–1918)

After the Balkan Wars, Bulgarians felt angry at Russia and the Western powers, believing they hadn't helped Bulgaria enough. The government of Vasil Radoslavov decided to align Bulgaria with Germany and Austria-Hungary. This also meant becoming an ally of the Ottomans, who were traditionally Bulgaria's enemies. But Bulgaria no longer had claims against the Ottomans. Meanwhile, Serbia, Greece, and Romania (allies of Britain and France) held lands that Bulgarians believed belonged to them.

Bulgaria waited during the first year of World War I to see how the war would go. But when Germany promised to restore Bulgaria's borders to what they were in the Treaty of San Stefano, Bulgaria, which had the largest army in the Balkans, declared war on Serbia in October 1915. Britain, France, and Italy then declared war on Bulgaria.

Bulgaria, allied with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottomans, won military victories against Serbia and Romania. They occupied much of Macedonia (taking Skopje in October), advanced into Greek Macedonia, and took Dobruja from the Romanians in September 1916. However, the war soon became unpopular with most Bulgarians. They faced great economic hardship and disliked fighting their fellow Orthodox Christians alongside the Muslim Ottomans. The leader of the Agrarian Party, Aleksandar Stamboliyski, was put in prison for opposing the war.

The Russian Revolution in February 1917 had a big effect in Bulgaria, spreading anti-war and anti-monarchy feelings among soldiers and in cities. Membership in socialist parties in Bulgaria grew rapidly. In June 1919, Radoslavov's government resigned. Soldiers started to rebel, Stamboliyski was released from prison, and a republic was declared.

The Years Between Wars

In September 1918, the Serbs, British, French, and Greeks broke through the front lines in Macedonia. Tsar Ferdinand was forced to ask for peace. Stamboliyski supported democratic changes, not a revolution. He had first appeared in Bulgarian politics in 1903 as a member of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BANU). In the August 1919 elections, BANU received a large share of the votes. To stop the revolutionaries, Stamboliyski convinced Ferdinand to step down as Tsar in favor of his son Boris III. The rebels were stopped, and the army was reduced.

Under the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (November 1919), Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline to Greece and most of its Macedonian territory to the new country of Yugoslavia. It also had to give Dobruja back to the Romanians. Elections in March 1920 gave the Agrarians a large majority, and Stamboliyski formed Bulgaria's first truly democratic government.

Stamboliyski faced huge social problems in what was still a poor country, mostly inhabited by small farmers. Bulgaria had to pay large war reparations to Yugoslavia and Romania. It also dealt with many refugees, as pro-Bulgarian Macedonians had to leave Yugoslav Macedonia. Despite these challenges, Stamboliyski was able to make many social reforms. However, he faced strong opposition from the Tsar, landowners, and army officers. Another fierce enemy was the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), which wanted a war to regain Macedonia for Bulgaria. Faced with these enemies, Stamboliyski allied with the Bulgarian Communist Party and started relations with the Soviet Union.

In March 1923, Stamboliyski signed an agreement with Yugoslavia, recognizing the new border and agreeing to stop VMRO. This caused a strong nationalist reaction. On June 9, there was a sudden takeover, and Stamboliyski was killed. A right-wing government led by Aleksandar Tsankov took power, supported by the Tsar, the army, and VMRO. This government began a harsh crackdown against the Agrarians and Communists. The Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov fled to the Soviet Union. There was severe repression in 1925 after a bomb attack on Sofia Cathedral. But in 1926, the Tsar convinced Tsankov to resign, and a more moderate government led by Andrey Lyapchev took office. An amnesty was announced, though Communists remained banned. The Agrarians reorganized and won elections in 1931 under Nikola Mushanov.

Just as political stability returned, the full effects of the Great Depression hit Bulgaria, and social tensions rose again. In May 1934, there was another takeover. The Agrarians were again suppressed, and an authoritarian government led by Kimon Georgiev was established with the Tsar's backing. In April 1935, Tsar Boris took power himself, ruling through puppet Prime Ministers Georgi Kyoseivanov (1935–1940) and Bogdan Filov (1940–1943). The Tsar's government banned all opposition parties and allied Bulgaria with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Although the Balkan Pact of 1938 improved relations with Yugoslavia and Greece, the issue of lost territories continued to be a problem.

World War II and What Came After

Under Filov's government, Bulgaria slowly moved towards World War II. It was encouraged by the return of southern Dobruja from Romania, ordered by Hitler in September 1940. In March 1941, Bulgaria officially signed the Tripartite Pact, and German troops entered the country. This was to prepare for the Axis invasions of Greece and Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia and Greece were defeated, Bulgaria was allowed to occupy all of Greek Thrace and most of Macedonia. Bulgaria declared war on Britain and the United States. However, it resisted German pressure to declare war on the Soviet Union, fearing pro-Russian feelings in the country.

In August 1943, Tsar Boris died suddenly after returning from Germany (possibly assassinated, though not proven). His six-year-old son Simeon II took his place. Power was held by a group of regents led by the young Tsar's uncle, Prince Kirill. The new Prime Minister, Dobri Bozhilov, mostly followed German orders.

Resistance against the Germans and the Bulgarian government grew widespread by 1943. It was mainly organized by the Communists. Along with the Agrarians, now led by Nikola Petkov, the Social Democrats, and many army officers, they formed the Fatherland Front. Resistance fighters operated in the mountainous western and southern regions. By 1944, it was clear that Germany was losing the war, and the Bulgarian government started looking for a way out. Bozhilov resigned in May, and his successor Ivan Ivanov Bagryanov tried to arrange talks with the Western Allies.

Meanwhile, the capital city of Sofia was bombed by Allied planes in late 1943 and early 1944. Other major cities were bombed later.

The Communist Takeover

But it was the Soviet army that was quickly moving towards Bulgaria. In August 1944, Bulgaria announced it was leaving the war and asked German troops to leave. Bulgarian troops were quickly pulled out of Greece and Yugoslavia. In September, the Soviets crossed Bulgaria's northern border. The government, desperate to avoid a Soviet occupation, declared war on Germany. But the Soviets couldn't be stopped, and on September 8, they declared war on Bulgaria. So, for a few days, Bulgaria was at war with both Germany and the Soviet Union. On September 16, the Soviet army entered Sofia.

The Fatherland Front took power in Sofia after a sudden takeover. They formed a broad government led by former ruler Kimon Georgiev, which included Social Democrats and Agrarians. According to the peace agreement, Bulgaria was allowed to keep Southern Dobruja, but it officially gave up all claims to Greek and Yugoslav territory. To prevent future arguments, 150,000 Bulgarians were forced to leave Greek Thrace.

The Communists at first played a small role in the new government, but the Soviet representatives were the real power in the country. A Communist-controlled People's Militia was set up, which bothered and scared non-Communist parties.

In February 1945, the new power structure in Bulgaria became clear when Prince Kirill and hundreds of other officials from the old government were arrested for war crimes. By June, Kirill and the other regents, 22 former ministers, and many others had been executed. In September 1946, the monarchy was ended by a public vote, and young Tsar Simeon was sent away. The Communists now openly took power, with Vasil Kolarov becoming President and Dimitrov becoming Prime Minister. Free elections promised for 1946 were boycotted by the opposition. In November 1945, the Fatherland Front won in a single-party election. The Agrarians refused to work with the new government, and in June 1947, their leader Nikola Petkov was arrested. Despite strong international protests, he was executed in September. This marked the final establishment of a Communist government in Bulgaria.

The Holocaust in Bulgaria

After 1940, Bulgaria passed several anti-Jewish laws. For example, Jews were not allowed in public service, were banned from certain areas, faced economic restrictions, and could not marry non-Jews. Bulgaria did deport some Jewish people from areas it controlled. Over 7,000 Jews were deported from Macedonia, which was under Bulgarian occupation.

Plans were made to deport Jews from Bulgaria itself in 1943, and 20,000 were expelled from Sofia. However, protests led by Dimitar Peshev and supported by political and religious leaders stopped further cooperation with Germany. This saved all of the 50,000 Jews living in Bulgaria. Sadly, in March 1943, almost 12,000 Jews in Thrace and Macedonia were deported to Auschwitz and Treblinka, where they were killed. You can learn more at Bulgarian Jews During World War II.

Bulgaria's Social History

Farming and Agrarianism

When Bulgaria gained freedom from Turkish rule, it was a poor, undeveloped country focused on farming. There was little industry or natural resources. Most of the land was owned by small farmers, and peasants made up 80% of the population of 3.8 million in 1900. Few Turkish nobles remained, and large land holdings were rare. However, many poor peasants lived on the edge of poverty.

Agrarianism was a very important political idea in the countryside. Farmers organized a movement that was separate from any existing political party. In 1899, the Bulgarian Agrarian Union was formed. It brought together educated people from rural areas, like teachers, with ambitious peasants. This union promoted modern farming methods and basic education.

Education in Bulgaria

The government supported modernization, especially by building many elementary and secondary schools. By 1910, there were 4,800 elementary schools, 330 high schools, 27 advanced high schools, and 113 vocational schools. From 1878 to 1933, France helped fund many libraries, research centers, and Catholic schools across Bulgaria. The main goals were to share French culture and language and to gain respect and business for France. Indeed, French became the main foreign language in Bulgaria, and wealthy families often sent their children to special Roman Catholic French language schools taught by French people.

The prosperous Greek community in southern Bulgaria set up its own network of Greek language primary and secondary schools. These schools promoted Greek culture to prevent their people from becoming fully absorbed into Bulgarian society. In 1888, a university was established. It was renamed the University of Sofia in 1904. Its departments of history, languages, physics, mathematics, and law trained people for government jobs. It became a center for German and Russian intellectual, philosophical, and religious ideas.

Turkish Minority

While most Turkish officials, landowners, businesspeople, and professionals left after 1878, some Turkish peasant villages remained. They made up about 10% of Bulgaria's population. They largely governed themselves, kept their traditional religion and language, and were tolerated by the Bulgarian government until the 1970s. They were protected as a minority group by international laws and agreements, including the Treaty of Berlin (1878). For over a century, this protection allowed Bulgaria's Turks to develop their own religious and cultural organizations, schools, local Turkish newspapers, and literature.

Growth of Cities

The first ten years of the 1900s saw steady growth and wealth. Cities grew constantly. The capital city of Sofia grew by 600% from 20,000 people in 1878 to 120,000 in 1912. This growth mainly came from peasants moving from villages to become laborers, traders, and office workers. Refugees from Turkish Macedonia also arrived, while very few people left Bulgaria.

Bulgaria had many different ethnic groups, with a main Orthodox Bulgarian population and many groups of Turks, Greeks, and others. Bulgarian revolutionaries from the Macedonian area (which was then under Ottoman rule) used Bulgaria as a base starting in 1894. They pushed for Macedonia to become independent from the Ottoman Empire so it could later more easily join with Bulgaria. They launched a poorly planned uprising in 1903 that was brutally put down. This led to tens of thousands more refugees pouring into Bulgaria.

See also

- Bulgarian irredentism

- Bulgarian unification

- European balance of power#19th century

- History of Europe#Nations rising

- Bulgarian National Revival and National awakening of Bulgaria

- September Uprising

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |