History of Gdańsk facts for kids

Historical affiliations

![]() Duchy of Poland 960s–1025

Duchy of Poland 960s–1025

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1025–1227

Kingdom of Poland 1025–1227

![]() Duchy of Pomerelia 1227–1282

Duchy of Pomerelia 1227–1282

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1282–1308

Kingdom of Poland 1282–1308

![]() Teutonic Order 1308–1410

Teutonic Order 1308–1410

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1410–1411

Kingdom of Poland 1410–1411

![]() Teutonic Order 1411–1454

Teutonic Order 1411–1454

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1454–1569

Kingdom of Poland 1454–1569

![]() Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569–1793

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569–1793

![]() Kingdom of Prussia 1793–1807

Kingdom of Prussia 1793–1807

![]() Free City of Danzig 1807–1814

Free City of Danzig 1807–1814

![]() Kingdom of Prussia 1814–1871

Kingdom of Prussia 1814–1871

![]() German Empire 1871–1918

German Empire 1871–1918

![]() Weimar Germany 1918–1920

Weimar Germany 1918–1920

![]() Free City of Danzig 1920–1939

Free City of Danzig 1920–1939

![]() Nazi Germany 1939–1945

Nazi Germany 1939–1945

![]() People's Republic of Poland 1945–1989

People's Republic of Poland 1945–1989

![]() Republic of Poland 1989–present

Republic of Poland 1989–present

Gdańsk (also known as Danzig in German) is one of Poland's oldest cities. It was founded by the Polish ruler Mieszko I in the 10th century. For a long time, it was part of the Piast state, either directly or as a dependent territory. In 1308, the city became part of the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights until 1454. After that, it rejoined Poland, gaining more freedom over time.

Gdańsk was a very important port city for Poland's grain trade. It attracted people from all over Europe. In 1793, during the Second Partition of Poland, Prussia took over the city. This made Gdańsk less important as a trading port. It was briefly a free city during the Napoleonic Wars. After Napoleon's defeat, it became Prussian again and later part of the new German Empire.

After World War I, the Free City of Danzig was created. This was a city-state watched over by the League of Nations. The German attack on the Polish military base at Westerplatte in 1939 marked the start of World War II. The city was then taken over by Nazi Germany. During this time, local Jews were systematically killed in the Holocaust. Poles and Kashubians also faced harsh treatment.

After World War II, Gdańsk became part of Poland again. Most of the city's German residents, who were the majority before the war, either ran away or were sent to Germany. This happened because of the Potsdam Agreement. After 1945, the city was rebuilt from war damage, and large shipyards were constructed. In the 1980s, Gdańsk was the center of the Solidarity strikes. After communism ended in 1989, many shipyards closed, leading to poverty and high unemployment.

Contents

- History of Gdańsk

- Early Settlements and Beginnings

- Founding by Polish Rulers

- Capital of Pomerelia

- Rule by the Teutonic Knights

- Flourishing in the Kingdom of Poland

- Under Prussian Rule

- Napoleonic Free City

- Back in the Kingdom of Prussia

- The Free City of Danzig (1920–1939)

- World War II (1939–1945)

- After World War II

- Famous People from Gdańsk

- Images for kids

History of Gdańsk

Early Settlements and Beginnings

The area around the Vistula river delta has been home to people for thousands of years. Settlements existed here many centuries before Christ.

Founding by Polish Rulers

It is believed that Mieszko I of Poland founded Gdańsk in the 980s. This connected the Polish state, ruled by the Piast dynasty, with the important trade routes of the Baltic Sea. The oldest signs of a medieval settlement were found where the Main Town Hall now stands. These early buildings were made from wood cut around 930 AD. Gdańsk became a major trade center after the nearby Viking Age trading post of Truso declined.

The first written mention of Gdańsk is from 999 AD. It describes how Saint Adalbert of Prague baptized people in urbs Gyddannyzc in 997. This city was said to separate the duke's great land from the sea. Not much more is known from written records for the 10th and 11th centuries.

Around the 11th century, a settlement started near the Great Mill. Later, in the 12th century, another settlement began near St. Catherine church. In the 1060s, a strong fort was built near the Motława river. This fort was made of wood cut between 1054 and 1063. Around 1112, the fort was rebuilt. This matches historical records that say Boleslaw III Wrymouth, a Polish king, took control of Pomerelia between 1112 and 1116.

From the mid-12th century, the settlement west of the fort grew a lot. A Romanesque church, St. Nicholas, was built in the second half of the 12th century. It was later replaced by another St. Nicholas church built by the Dominicans in 1223-1241. In 1168, the Cistercians built a monastery in nearby Oliwa, which is now part of Gdańsk.

Capital of Pomerelia

By the end of the 11th century, Poland lost control of Pomerelia. It regained it in the 12th century. Poland then split into several self-governing areas. Gdańsk became the main fort of the Samborides family, who ruled Pomerelia. Important dukes like Mestwin I, Swietopelk II, and Mestwin II lived here.

In 1226, pagan Old Prussians attacked the monastery in Oliwa. Around 1235, Gdańsk had about 2,000 people. Swietopelk II gave the city special rights, similar to those in Lübeck. Merchants from the Hanseatic League cities of Lübeck and Bremen started to settle in Gdańsk after 1257. The city officially became a city in 1224. It grew into an important trading and fishing port on the Baltic Sea. In 1282/1294, Mestwin II, the last duke of Pomerelia, gave all his lands, including Gdańsk, to Przemysł II, who soon became King of Poland. This reunited Gdańsk with the Kingdom of Poland.

Rule by the Teutonic Knights

In the early 14th century, Poland and Brandenburg were at war over the region. When Brandenburg attacked Gdańsk, Poland's King Władysław I could not help. So, the city asked the Teutonic Knights for help. The Knights drove out the Brandenburgers in 1308 but did not give the city back to Poland. The people of Gdańsk rebelled, but the Knights violently put down the uprising. Many people were killed, and parts of the town were destroyed.

The Knights then took over the rest of Pomerelia. In 1309, Brandenburg sold its claim to the Teutonic Order. Gdańsk, now called Danzig, became part of the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights. Poland and the Teutonic Order, who used to be allies, fought a series of wars after the Knights took Pomerelia.

Between 1361 and 1416, the city's citizens rebelled against the Knights several times. In 1410, during the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War, the city council recognized the Polish king, Władysław Jagiełło, as their ruler. After the war ended in 1411, Jagiełło released the city from its promise, and it went back to Teutonic rule. The Knights then punished the people of Gdańsk for supporting the Polish king.

The city's growth slowed down after the Teutonic Knights took over. The new rulers tried to reduce Gdańsk's economic power by removing its local government and trade rights. However, Gdańsk defended its independence and became the largest and most important seaport in the region. It joined the Hanseatic League in 1361. The city grew rich from trade with Poland, especially along the Vistula river.

Polish kings, like Władysław and Casimir III the Great, always questioned the Teutonic Order's takeover of Gdańsk. This led to wars and legal cases. Peace was made in 1343, but the Knights kept control of Gdańsk for a while.

Flourishing in the Kingdom of Poland

In 1440, Gdańsk helped create the Prussian Confederation, an organization against the Teutonic Knights. The Confederation complained that the Knights often imprisoned or killed local leaders without trial. In 1454, King Casimir IV Jagiellon brought the territory back into the Kingdom of Poland. The city was allowed to make Polish coins. The mayor swore loyalty to the King in 1454, recognizing the Knights' earlier rule as illegal. In 1457, King Casimir IV gave the city new special rights.

During the Thirteen Years' War (1454–1466), Gdańsk's fleet fought for Poland, winning important battles. The war ended in 1466 with the Knights' defeat. With the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), the Teutonic Knights gave up their claims to Gdańsk. The city was recognized as part of Poland, within the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

The 15th and 16th centuries brought many cultural changes to Gdańsk. This included new art, language, and scientific contributions. In 1471, a ship from Gdańsk brought the famous painting The Last Judgment by Hans Memling to the city. Around 1480–1490, tablets showing the Ten Commandments in Middle Low German were put up in St. Mary's Church.

Nicolaus Copernicus visited the city in 1504 and 1526. His first printed work about his heliocentric theory, Narratio Prima, was published here in 1540.

The Protestant Reformation gained support in Gdańsk. In 1520, Lutheran writings were printed. In 1557, the Lutheran Eucharist was allowed, and both religions were tolerated.

From 1563, Dutch architects designed many streets in the Dutch Renaissance style. In 1566, the city's official language changed from Middle Low German to standard German. The Polish language was taught in the local Academic Gymnasium from 1589.

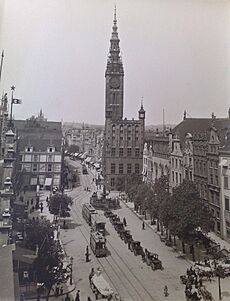

In the 16th century, Gdańsk was the largest and most important city in Poland. Most people spoke German. The city had voting rights during the election of Polish kings. Gdańsk grew rich, and many famous landmarks were built, like the Highland Gate, Golden Gate, Neptune's Fountain, and the Green Gate. The Main Town Hall was completed, with a golden statue of Polish King Sigismund II Augustus on top.

In 1577, King Stephen Báthory's army besieged Gdańsk for six months. A deal was made where Báthory confirmed the city's special status and laws. The city recognized him as ruler and paid a large sum of money.

In 1606, a distillery called Der Lachs (German for "the Salmon") was founded. It made Danziger Goldwasser, a famous liqueur. Around 1640, Johannes Hevelius set up his astronomical observatory in the Old Town. Polish King John III Sobieski often visited Hevelius.

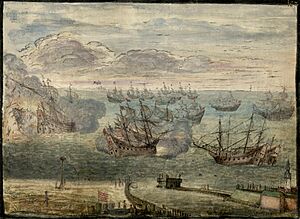

From the 14th to the mid-17th century, Gdańsk grew quickly. It became the largest city on the Baltic Sea, thanks to its trade with the Netherlands and handling most of Poland's sea trade via the Vistula River. However, wars with Sweden (1626–1629 and 1655–1660) and a plague in 1709 severely affected the city. In 1627, the Battle of Oliwa was fought near the city, a major victory for the Polish Navy. In 1655, the Swedish king attacked Poland and came near Gdańsk, but did not besiege it. The war ended in 1660 with the Treaty of Oliwa.

By 1650, most people in Gdańsk were Lutheran. A large number of Lutherans also spoke Polish. Gdańsk took part in all Hanseatic League meetings until 1669. By then, other countries had taken over much of the Baltic trade. In 1677, a Polish-Swedish alliance against Brandenburg was signed in the city.

In 1734, Russian forces briefly occupied the city after a long siege during the War of the Polish Succession. The city, which supported the losing candidate for the throne, had to pay for the damage.

The future Polish king Stanisław August Poniatowski lived in Gdańsk until he was seven. His brother, Michał Jerzy Poniatowski, who became the Primate of Poland, was born in the city. In 1743, the Danzig Research Society was formed.

Under Prussian Rule

After the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Gdańsk fought hard to stay part of Poland. However, in 1793, during the Second Partition of Poland, Prussian forces took over the city. It became part of the Kingdom of Prussia. Many people in Gdańsk, both German and Polish speakers, did not want to be part of Prussia. Some, like the family of Arthur Schopenhauer, chose to leave. The mayor and a city councilor resigned in protest.

Napoleonic Free City

After Napoleon defeated the Fourth Coalition, he created the semi-independent Free City of Danzig (1807–1814). This happened after French, Polish, and Italian troops captured the city in 1807. Gdańsk returned to Prussia in 1814 after Napoleon's defeat.

Back in the Kingdom of Prussia

From 1824 to 1878, East and West Prussia were combined into one province. As part of Prussia, Gdańsk joined the Zollverein (a customs union) and sent representatives to the German National Assembly in 1848. In the late 19th century, more Poles moved into the city, and some local people rediscovered their Polish heritage.

In 1871, Gdańsk became part of the new German Empire. The Polish minority in the city started to organize in the 1870s and 1880s, forming groups and a Polish bank. A Polish newspaper, Gazeta Gdańska, was printed in 1891. In 1907, Poles protested against Prussian policies that tried to make them more German, including banning the Polish language.

The Free City of Danzig (1920–1939)

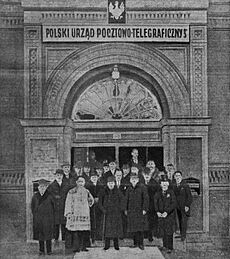

After Germany lost World War I, the Allied powers created the Free City of Danzig in 1919. This city-state included Gdańsk, its port, and the surrounding area. It was overseen by the League of Nations. The people of Danzig received their own citizenship. The city also had a customs union with Poland, and Poland had rights to use the harbor, a Polish post office, and a small Polish military base at Westerplatte. This arrangement was based on the city's long history with Poland.

In 1923, about 3.7% of the city's population was Polish. In the 1920s and 1930s, over 90% of the city's population was German. However, some estimates suggest the Polish population was higher, around 6% to 13%. Poles faced discrimination and unfair treatment from German officials in the Free City.

The Free City of Danzig had its own stamps and money. Poland aimed to have free access to the sea. During the Polish-Soviet War, Danzig workers went on strike to stop ammunition from reaching the Polish army. Because of this, Poland built a large military port in Gdynia, only 25 km away. Gdynia was directly controlled by Poland and quickly became a major Polish port.

A trade war between Germany and Poland (1925-1934) made Poland focus on international trade. A new railway line connected Silesia with the coast, making it cheaper to send goods through Polish ports. Gdynia became the biggest port on the Baltic Sea.

The desire to rejoin Germany grew strong in Danzig. This led to the election of a National Socialist government in 1933. A non-aggression agreement was signed between Germany and Poland. However, as Nazism grew, anti-Polish feelings increased. Poles faced discrimination in jobs and education. Polish children were often denied entry to Polish-language schools. Attacks on Polish homes and schools occurred.

From 1937, German companies were not allowed to hire Poles, and Poles were fired. Using Polish in public places was banned. In 1938, Germans attacked over 100 Polish homes. Before World War II began in 1939, Polish railway workers were arrested.

Many members of the Jewish Community of Danzig left the city after a pogrom in 1937. After the Kristallnacht riots in 1938, the Jewish community decided to leave. By September 1939, only about 1,700 mostly elderly Jews remained. They were later sent to ghettos and extermination camps.

World War II (1939–1945)

In October 1938, Germany demanded that Danzig rejoin Germany. On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. On September 2, 1939, Germany officially took over the Free City. In October 1939, Danzig became part of a German administrative district called Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia.

With the war, the Nazi regime began its plan to kill Poles, Kashubians, Jews, and political opponents. They were sent to concentration camps, like nearby Stutthof, where many victims died. In September 1939, Germans arrested over 800 Polish railway workers, who were later killed. Local Polish activists were also arrested and executed.

During the war, the Germans ran a Nazi prison in the city. They also had a camp for Romani people, and several subcamps for Allied prisoners of war (POWs). Hundreds of prisoners in the city were subjected to cruel Nazi executions and experiments. German courts in the occupied areas used terms like "Polish subhumans" and gave Poles harsher sentences because of their supposed racial inferiority.

The Polish resistance movement was active in Gdańsk. Poles smuggled documents about German weapons, spied on local German industries, and helped distribute underground Polish newspapers. The resistance also helped endangered Polish members and British POWs escape to neutral Sweden through the city's port.

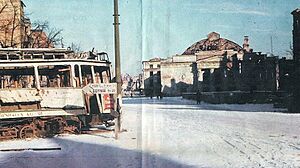

In early 1945, as the Nazi state was collapsing, Germany began evacuating civilians from Danzig. Most Germans fled the city, many by sea, to Schleswig-Holstein. This happened in winter, under constant threat of bombs and submarines.

After a siege, the Soviet Red Army occupied a largely destroyed Danzig on March 30, 1945.

After World War II

With Germany's defeat, the planned killing of the Polish population was stopped, and Poles returned to Gdańsk. The Yalta Conference had already agreed to place the city, under its Polish name Gdańsk, under Poland's control. This decision was confirmed at the Potsdam Conference.

A Polish government was set up in Gdańsk on March 30, 1945. New Polish residents moved to Gdańsk. By 1948, more than two-thirds of the 150,000 residents came from Central Poland. About 15-18% came from Polish-speaking areas taken by the Soviet Union. Many local Kashubians also moved to the city. The German population was deported starting in July 1945.

Between 1952 and the late 1960s, Polish artisans rebuilt much of the old city's buildings, which were up to 90% destroyed in the war. The decision to rebuild the old town was political. It was meant to show the city's reunification with Poland. The reconstruction focused on an idealized pre-1793 look, ignoring 19th and early 20th-century German architecture.

In 1946, the communist government executed 17-year-old Danuta Siedzikówna and 42-year-old Feliks Selmanowicz, who were Polish resistance members.

Gdańsk was one of three Polish ports where Greeks and Macedonians, who were refugees of the Greek Civil War, arrived in Poland. In 1949, four groups of Greek and Macedonian refugees arrived at the port of Gdańsk.

Gdańsk was the site of anti-government protests in December 1970. These protests led to the downfall of Poland's communist leader. Ten years later, Gdańsk was the birthplace of the Solidarity trade union movement. Solidarity's opposition helped end communist rule in 1989. Its leader, Lech Wałęsa, was elected president of Poland. Today, Gdańsk remains a major port and industrial city.

In 2014, the remains of Danuta Siedzikówna and Feliks Selmanowicz were found. Their state burial was held in Gdańsk in 2016, with thousands of people attending.

Gdańsk has recently hosted many international sports events. These include UEFA Euro 2012 and several volleyball and handball championships.

Famous People from Gdańsk

Many notable people were born or lived in Gdańsk:

- Johannes Hevelius, 1611, a famous astronomer.

- Aleksander Benedykt Sobieski, 1677, a Polish prince.

- Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, 1686, a physicist and engineer known for the Fahrenheit temperature scale.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, 1788, a well-known philosopher.

- Günter Grass, 1927, a famous writer and philosopher.

- Donald Tusk, 1957, a politician and former prime minister of Poland.

- Dariusz Michalczewski, 1968, a famous boxer.

- Lech Wałęsa, born 1943, a trade union activist and former president of Poland, lived and worked in Gdańsk.

Images for kids